Euphoria and Panic Bubbles in Presidential Debate Evaluations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The King Premieres on Independent Lens Monday, January 28 on PBS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Tanya Leverault, ITVS 415-356-8383 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit pbs.org/pressroom The King Premieres on Independent Lens Monday, January 28 on PBS Climb into Elvis’s 1963 Rolls-Royce for a Musical Road Trip and Timely Meditation on Modern America Online Streaming Begins January 29 (San Francisco, CA) — Forty years after the death of Elvis Presley, two-time Sundance Grand Jury winner Eugene Jarecki takes the King’s 1963 Rolls-Royce on a musical road trip across America. From Tupelo to Memphis to New York, Las Vegas, and countless points between, the journey explores the rise and fall of Elvis as a metaphor for the country he left behind. What emerges is a visionary portrait of the state of the American dream and a penetrating look at how the hell we got here. The King premieres on Independent Lens Monday, January 28, 2019, 9:00-10:30PM ET (check local listings) on PBS. Far more than a musical biopic, The King is a snapshot of Credit: David Kuhn America at a critical time in the nation’s history. Tracing Elvis’ life and career from his birth and meteoric rise in the deep south to his tragic and untimely end in Hollywood and Las Vegas, The King covers a vast distance across contemporary America, painting a parallel portrait of the nation’s own heights and depths, from its inspired origins to its perennial struggles with race, class, power, and money. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

No City Limits 2019 Agenda

NO CITY LIMITS 2019 AGENDA WELCOME Sheldon Danziger (Russell Sage Foundation); Wes Moore (Robin Hood) INTRODUCTION: THE MOBILITY IMPERATIVE Marta Tienda (Board NCL Advisory Committee; Princeton University, Department of Sociology and Woodrow Wilson School) MOBILITY FROM POVERTY IN THE UNITED STATES: RACE, GENDER, AND GEOGRAPHY Raj Chetty (Harvard University and Opportunity Insights) ADDRESSING MOBILITY IN DIFFERENT GEOGRAPHIES Daniel Lurie (Tipping Point Community); Rachel Garbow Monroe (The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation); Wes Moore (Robin Hood); Moderator: Nisha Patel (Robin Hood) THE STATE OF POVERTY AND MOBILITY IN NYC Geoff Canada (Board NCL Advisory Committee; Harlem Children’s Zone); Jane Waldfogel (Columbia University); Moderator: Sarah Oltmans (Robin Hood) LEARNING FROM THE EXPERTS: ENGAGING COMMUNITY IN MOBILITY SOLUTIONS Blue Ridge Labs Design Insight Group Members; Moderator: Kaya Henderson (Board NCL Advisory Committee; Teach For All) MOBILITY THEN AND NOW Nicholas Kristof (The New York Times); Wes Moore (Robin Hood); Moderator: Katie Couric (Katie Couric Media) INTRODUCTION: THE INTERSECTION OF POLICY AND PRACTICE John King, (Board NCL Advisory Committee; Education Trust) LESSONS FROM THE FIELD: THE IMPACT OF POLICY ON COMMUNITY AND MOBILITY Judith Browne Dianis (Advancement Project); Katherine O’Regan (NYU Wagner and NYU Furman Center); Michael Tubbs (Mayor of Stockton, CA); Moderator: John King (Board NCL Advisory Committee; Education Trust) INTRODUCTION: SHIFTING THE NARRATIVE Steve Stoute (NCL Board Advisory Committee; Translation and UnitedMasters) HOW RACIAL STEREOTYPING IMPACTS NARRATIVES ABOUT POVERTY Jennifer L. Eberhardt (Stanford University) TELLING A NEW STORY: SETTING THE GROUNDWORK FOR NARRATIVE CHANGE Heather McGhee (Demos); Soledad O’Brien (Starfish Media Group); John Ridley (Filmmaker); Rashad Robinson (Color Of Change); Moderator: Van Jones (CNN) OUR COLLECTIVE FUTURE Jim Shelton (Amandla Enterprises); Wes Moore (Robin Hood) CLOSING Wes Moore (Robin Hood). -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

We Organize for Knowledge and Empowerment 2017 Conference Booklet

W.O.K.E. ‘17 An Institute for College Men of Color We Organize for Knowledge and Empowerment 2017 Conference Booklet Saturday, May 6, 2017 Chicago, Illinois Letter from the Conference Chairs Greetings, Welcome to the inaugural We Organize for Knowledge and Empowerment Conference a.k.a. W.O.K.E. 17! We are glad that you took the time to join us for what is sure to be a dynamic day. There are a number of conference in the United States that are specifically geared towards undergraduate men. Most of which, engage men in masculinity work, but fail to address issues of race and the intersections of race and gender. Our goal was to produce a one-day conference experience which addresses the intersection of race and gender grounded in theory. In this one-day conference we aim to explore the identities of men of color and their socialization within the United States. Using the Cycle of Liberation as a framework for the schedule, you all as undergraduate men of color will engage deeply around your identities, name injustices, build community within and outside of your racial identity, and begin to construct an action plan to combat racism and sexism in your communities. The conference will be divided into five stages that mirror the five beginning levels of the Cycle of Liberation. Using Cycle of Socialization, Privilege Identity Exploration, and Critical Race Theories, we hope you will begin to work through a critical consciousness towards creating effective change in society. Get ready to WAKE UP the activist in you! Let’s get to work. -

January 2014 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

January 2014 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data January 5, 2014 27 men and 10 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 6 men and 3 women Janet Napolitano (F) Gene Sperling (M) Jim Cramer (M) Dr. Delos Cosgrove (M) Dr. John Noseworthy (M) Steve Schmidt (M) Rep. Donna Edwards (F) Judy Woodruff (F) Chuck Todd (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 6 men and 1 woman Sen. Harry Reid (M) Rep. Peter King (M) Rep. Matt Salmon (M) Peggy Noonan (F) David Ignatius (M) David Sanger (M) John Dickerson (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 5 men and 2 women Sen. Rand Paul (M) Sen. Chuck Schumer (M) Cokie Roberts (F) Bill Kristol (M) Ana Navarro (F) Fmr. Gov. Brian Schweitzer (M) Ben Smith (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 1 woman Gov. Scott Walker (M) Gene Sperling (M) Stuart Rothenberg (M) Cornell Belcher (M) Mattie Dupler (F) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 5 men and 3 women Fmr. Gov. Mitt Romney (M) Ilyse Hogue (F) Mark Rienzi (M) Brit Hume (M) Amy Walter (F) George Will (M) Charles Lane (M) Doris Kearns Goodwin (F) January 12, 2014 27 men and 10 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 7 men and 4 women Reince Priebus (M) Mark Halperin (M) Chuck Todd (M) Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake (F) Kimberley Strassel (F) Maria Shriver (F) Fmr. Sen. Rick Santorum (M) Jeffrey Goldberg (M) Fmr. Rep. Jane Harman (F) Chris Matthews (M) Harry Smith (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 7 men and 1 woman Sen. -

Anti-Racist Info

This resource list is very incomplete … just a drop in the bucket! Books (others listed in podcasts and resource lists): Alexander, Michelle (2010, 2012, 2020) The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness and 1/17/20 Ten Years After The New Jim Crow Baldwin, James – all Billings, David (2016) Deep Denial: The Persistence of White Supremacy in the United States Cohen, Cathy J. Democracy Remixed: Black Youth and the Future of American Politics Davis, Angela, et.al (2016) Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement Gaines, Ernest (1993) A Lesson Before Dying Glaude, Eddie S. (2020) Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own; (2017) Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul; (2008) In a Shade of Blue: Pragmatism and the Politics of Black America Kendi, Ibram X. & Lukashevsky, Ashley (2020) Antiracist Baby board book and hard copy. Interview with Kendi on the book 7/24/20: Teaching children to be antiracist Kendi, Ibram X. (2019) How to Be an Antiracist; (2017) Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America Dr. Kendi is the professor in the Department of History in the College of Arts & Sciences (as of June 11, 2020) who will establish the BU Center for Antiracist Research King, Ruth (2018) Mindful of Race: Transforming Racism from the inside Out Lopez, William D. (2020). Separated: Family and Community in the Aftermath of an Immigration Raid – relates police violence in Black communities and immigration violence in Latinx communities while sharing life stories. -

Colorblind: How Cable News and the “Cult of Objectivity” Normalized Racism in Donald Trump’S Presidential Campaign Amanda Leeann Shoaf

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University MA in English Theses Department of English Language and Literature 2017 Colorblind: How Cable News and the “Cult of Objectivity” Normalized Racism in Donald Trump’s Presidential Campaign Amanda Leeann Shoaf Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/english_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Shoaf, Amanda Leeann, "Colorblind: How Cable News and the “Cult of Objectivity” Normalized Racism in Donald Trump’s Presidential Campaign" (2017). MA in English Theses. 20. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/english_etd/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English Language and Literature at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA in English Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please see Copyright and Publishing Info. Shoaf 1 Colorblind: How Cable News and the “Cult of Objectivity” Normalized Racism in Donald Trump’s Presidential Campaign by Amanda Shoaf A Thesis submitted to the faculty of Gardner-Webb University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English Boiling Springs, N.C. 2017 Approved by: ________________________ Advisor’s Name, Advisor ________________________ Reader’s Name _______________________ Reader’s Name Shoaf 2 COLOBLIND: HOW CABLE NEWS AND THE “CULT OF OBJECTIVITY” NORMALIZED RACISM IN DONALD TRUMP’S PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN Abstract This thesis explores the connection between genre and the normalization of then-presidential candidate Donald Trump’s varied racist, sexist, and xenophobic comments during the height of the 2016 General Election Examining the genre of cable news and the network CNN specifically, this thesis analyzes both the broad genre-specific elements and specific instances during CNN’s panel discussions where that normalization occurred. -

Interview with Otis Cunningham Danny Fenster

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Chicago Anti-Apartheid Movement Oral Histories Fall 2009 Interview with Otis Cunningham Danny Fenster Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_caam_oralhistories Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, American Politics Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Cultural History Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, International Relations Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Fenster, Danny. "Interview with Otis Cunningham" (Fall 2009). Oral Histories, Chicago Anti-Apartheid Collection, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_caam_oralhistories/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Oral Histories at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago Anti-Apartheid Movement by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Transcription: Danny Fenster 1. Interviewer: Danny Fenster 2. Interviewee: Otis Cunningham 3. Date: 12112/09 4. Location: Otis's home in the Beverly neighborhood on Chicago's southwest side. 5. 20 years of activism 6. Activism in Chicago 7. Otis YOB: 1949, Chicago born and raised 8. Father and Mother both born in Chicago 9. Otis Cunningham: ... Probably sixth grade or so. Fifth grade or so. Because see 10. I was born in '49. So--uh, urn, I'm, uh, five years old when Brown versus Board 11. -

Mdsa T1344 134.Pdf

INDEX OF BIRTHS CODE SURNAME MOTHERS RACE SEX DATE OF BIRTH REGISTERED MAIDEN PiAME MO DAY YR NUMBER HOOO HGWE 8AR8ARA ANN HAAS 1 2 16 71 11445 HOOO HUH CHUN SUK RQ 6 1 23 71 03133 HOOO HOWIE DENNIS WILLI ZELU80USKI 1 2 1 31 71 01874 HOOO HAY DONALD BRYAN CODY 1 1 5 08 71 07735 HOOG HAY EDWARD FLEMI MITCHELL 1 2 9 24 71 15913 HOOO HOkE ELMER HAMILT HURT'f 2 1 1 03 71 €0199 HOOO HAY GREGORY EVER OTTO - 1 1 3 12 71 13410 HOOQ -mm- TCJHW HQWSO^ TAYLOR' -2S~ IX- -10711 HOOO HOY LINDA LEE MOATS 1 2 11 06 71 19021 HOOO hq£y LYOtA MAE COFIELD 2 2 12 26 71 21778 HOOO HO MING YUEN LAI 4 2 3 02 71 03650 HOOO HOOE ROBERT EUGIE 0 NEILL 1 2 4 07 71 G6i 10 HOOO HAY RONALD GILBE LIGGETT I 2 3 02 71 03438 HOOO HOY «ILLI AM RICH PARKS 1 1 6 26 71 10801 HOOO HUEY ZOLLie MAE HURT 2 2 1 21 71 01474 HlOO HOPP AMTHONY IRV1 PATEK 1 2 1 14 71 00627 HlOO HIPP CHARLES TAYLOR 1 1 5 18 71 08722 HlOG HAUF DIANE LYNN vallgrtigara 1 X 10 08 71 17783 HlOO HUFF FREDERICK JC DECKER 1 1 10 18 71 17821 HlOO HUFF JACK JEROME SMITH 1 1 1 28 71 01735 HlOO HOPE JAMES GEORGE POPE 2 2 12 29 71 21750 HlOO HUFF JANICE SUE SPENCER, 2 2 12 25 71 21409 HlOO HIPP JOHN WARREN MC GOWAN 1 1 10 19 71 17741 HlOO HAUF JOHN FRANKLI WILSON 1 2 8 19 71 13753 HlOO HUFF JOSEPHINE F WILLIAKSGN 2 2 2 06 7l 025SS Hi 00 HOF MARIAN GERTR MARGARITAS 1 1 3 14 71 04,411 HlOO HAUF MARTIN CARL BEECHER 1 1 g 22 71 16000 >1100 -H A ^ -4= i"! Q—i -34^ INDEX OF BIRTHS CODE SURNAME MOTHERS RACE SEX DATE OF BIR H REGISTERED MAIDEN NAME MO DAY Y NUMBER HlOO HOPE PATRICIA 01A HILL 2 1 12 19 21211 16956 HlOO HOPPA -

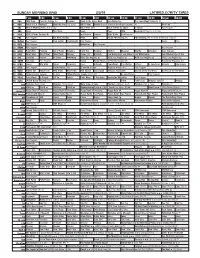

Sunday Morning Grid 2/3/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/3/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) Pregame Road to the Super Bowl Tony Romo Sp. The Super Bowl Today (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Hockey Boston Bruins at Washington Capitals. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News NBA Basketball: Thunder at Celtics 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday News PBC Inside PBC Boxing (N) PBA Bowling CP3 Celebrity Invitational. (Taped) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Suze Orman’s 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Feel Better Fast and Make It Last With Daniel Joni Mitchell Live at Isle 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Van Jones Visits Santa Clara

THE ADVOCATE Santa Clara University School of Law School of Law Newspaper Since 1970 Thursday, April 21, 2016 Volume 46 Issue 6 SCU Law Hosts Celebration of Achievement Awards By Nikki Webster man for others,” as demonstrated by his Editor Emeritus commitment to excellence, ethics, and social justice. Boscia says that his calling Every year, Santa Clara Law and is to serve others and to do good in its Alumni Association host the the world. He encourages law students Celebration of Achievement to “honor to find a cause, pursue it, and make a lawyers who lead.” On March 19th, difference. our legal community gathered at the Katherine Alexander, the founder of Fairmont Hotel to recognize this the Katherine and George Alexander year’s award recipients. Community Law Clinic, received the Professor Emeritus Father Paul Santa Clara Law Amicus Award this year. Goda introduced the event by Since 2009, we have given the award defining achievement: to stand to recognize a true friend of the law something on its head, to come to school. The recipient is someone who an end. Father Goda expounded INSERT CAPTION AND GIVE CREDIT TO JOANNE has demonstrated the highest level of that we were gathered both to leadership in the legal profession and the honor and to build upon the Celebration of Achievement Awards Ceremony. Photo Credit: Adam Hayes community, and who has significantly honorees’ contributions. Celebrating celebrated their dedication to our community. advanced the mission and reputation of achievement is about more than just giving This year’s Young Alumnus Rising Star went to Santa Clara Law.