The Metis Homeland: Its Settlements and Communities1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WRRDA in the Great Lakes

WRRDA in the Great Lakes Honorary cosponsors of this briefing are House Great Lakes Task Force Co-Chairs Congresswoman Miller, Congressman Dingell, Congressman Duffy, & Congresswoman Slaughter Friday, September 13, 2013 Longworth House Office Building 1310 2:00 p.m. Speakers: Steve Fisher, American Great Lakes Ports Association Jim Weakley, Lake Carriers Association Matt Doss, Great Lakes Commission Speakers will help staff understand: • How a Water Resources Development Act can impact the Great Lakes economy and ecosystem; • Potential impacts include dredging and other operations and maintenance, as well as invasive species and ecosystem restoration; • The House Water Resources Reform and Development Act, as it pertains to the Great Lakes; and • A comparison to the Senate version’s impacts on the Great Lakes. LAKE CARRIERS’ ASSOCIATION The Greatest Ships on the Great Lakes & GREAT LAKES MARITIME TASK FORCE Our Message • The Great Lakes is an important national resource • The Great Lakes Navigation System (GLNS) is a great investment • The GLNS is an endangered SYSTEM • The Soo Locks and the St. Marys River are a SINGLE POINT OF FAILURE for the GLNS National Economic Impact • The Great Lakes Region is responsible for: – 70% of All U.S. Auto Manufacturing – 55% of All U.S Manufacturing Output – 50% of All U.S. Steelmaking Capacity – 34% of All U.S. Manufacturing jobs – 26 % of the nation’s top 100 harbors by tonnage – 10% of All U.S. domestic waterborne cargo – 3.2% of GDP depends on Soo Lock WATERBORNE TRANSPORTATION IS ... Safer More Fuel-Efficient Fewer Emissions THAN RAIL OR TRUCK TRANSPORTATION Miles 1 Ton of Cargo Carried Tons of CO2 Produced to Transport Per Gallon of Fuel 1 Fuel Cost 1,000 Tons of Cargo 1,000 Miles 2 per mile Percent above (cents) Laker fuel cost 3 6.60 Truck 929% 59 190 200% 1.93 Rail 202 55 0.76 Barge 18% 514 22 Great Lakes 607 18 Carrier 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 0.64 25 50 75 100 125 175 200 Miles Tons CO2 1. -

(HSA) Generated Sunday January 24 2021

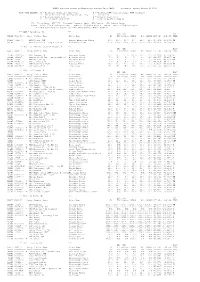

NCRFC forecast points by Hydrologic Service Area (HSA) Generated Sunday August 15 2021 FCST TYPE LEGEND: B - Benchmark Tributary (Apr-Oct) H - Headwater/WFO Site Specific (FFH guidance) D - Daily morning fcst during drought only I - Inflow fcst E - Evening daily fcst M - Morning daily fcst F - Flood event-only fcst W - Long Range Water Supply FS - Flood Stage RFC FIS - Forecast Issuance Stage WFO Action - WFO Action Stage MINOR - Minor flooding begins MOD - Moderate flooding begins MAJOR - Major Flooding Begins # - Not currently an active realtime USGS Surface Water Station. *** ABR - Aberdeen, SD *** RFC WFO FCST NWSLI USGS ID Group Station Name River Name FS FIS Action MINOR MOD MAJOR LAT (N) LON (W) TYPE ----- ---------- ----- ------------ ---------- -- --- ------ ----- --- ----- ------- ------- ---- PVRS2 05290000 MIN Peever 6NE Little Minnesota River 17.0 16.0 16.0 17.0 22.0 24.0 45.6161 96.8753 FH BSLM5 MIN Ortonville - Big Stone Lk Minnesota River 971.5 970.5 970.5 971.5 973.0 975.0 45.3092 96.4681 F *** APX - N. Central Lower Michigan, MI *** RFC WFO FCST NWSLI USGS ID Group Station Name River Name FS FIS Action MINOR MOD MAJOR LAT (N) LON (W) TYPE ----- ---------- ----- ------------ ---------- -- --- ------ ----- --- ----- ------- ------- ---- SHRM4 04124000 NLM Sherman 1N Manistee River 15.0 14.0 14.0 15.0 16.0 17.0 44.4364 85.6986 MF MYFM4 04126970 NLM Mayfield 5NE - Brown Brdg Rd Boardman River 7.0 5.0 5.0 7.0 9.0 11.0 44.6567 85.4367 FH RDOM4 04136000 NLM Red Oak 3S Au Sable River 7.0 6.0 6.0 7.0 8.0 9.0 44.6769 84.2925 MF -

Guide to the Geology of the Mount Carmel Area, Wabash County, Illinois

557 IL6gui 1996-D Guide to the Geology of the Mount Carmel Area, Wabash County, Illinois W.T. Frankie, R.J. Jacobson, and B.G. Huff Illinois State Geological Survey M.B. Thompson Amax Coal Company K.S. Cummings and C.A. Phillips Illinois Natural History Survey Field Trip Guidebook 1996D October 26, 1996 Department of Natural Resources ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ON THE BANKS OF THE WABASH, FAR AWAY VERSE 1 Round my Indiana homestead wave the corn fields, In the distance loom the woodlands clear and cool. Often times my thoughts revert to scenes of childhood, Where I first received my lessons, nature's school. But one thing there is missing in the picture, Without her face it seems so incomplete. I long to see my mother in the doorway, As she stood there years ago, her boy to greet! CHORUS Oh, the moonlight's fair tonight along the Wabash, From the fields there comes the breath of new mown hay. Through the sycamores the candle lights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash, far away. VERSE 2 Many years have passed since I strolled by the river, Arm in arm with sweetheart Mary by my side. It I was there tried to tell her that I loved her, It was there I begged of her to be my bride. Long years have passed since I strolled through the churchyard, She's sleeping there my angel Mary dear. I loved her but she thought I didn't mean it, Still I'd give my future were she only here. -

Charted Lakes List

LAKE LIST United States and Canada Bull Shoals, Marion (AR), HD Powell, Coconino (AZ), HD Gull, Mono Baxter (AR), Taney (MO), Garfield (UT), Kane (UT), San H. V. Eastman, Madera Ozark (MO) Juan (UT) Harry L. Englebright, Yuba, Chanute, Sharp Saguaro, Maricopa HD Nevada Chicot, Chicot HD Soldier Annex, Coconino Havasu, Mohave (AZ), La Paz HD UNITED STATES Coronado, Saline St. Clair, Pinal (AZ), San Bernardino (CA) Cortez, Garland Sunrise, Apache Hell Hole Reservoir, Placer Cox Creek, Grant Theodore Roosevelt, Gila HD Henshaw, San Diego HD ALABAMA Crown, Izard Topock Marsh, Mohave Hensley, Madera Dardanelle, Pope HD Upper Mary, Coconino Huntington, Fresno De Gray, Clark HD Icehouse Reservior, El Dorado Bankhead, Tuscaloosa HD Indian Creek Reservoir, Barbour County, Barbour De Queen, Sevier CALIFORNIA Alpine Big Creek, Mobile HD DeSoto, Garland Diamond, Izard Indian Valley Reservoir, Lake Catoma, Cullman Isabella, Kern HD Cedar Creek, Franklin Erling, Lafayette Almaden Reservoir, Santa Jackson Meadows Reservoir, Clay County, Clay Fayetteville, Washington Clara Sierra, Nevada Demopolis, Marengo HD Gillham, Howard Almanor, Plumas HD Jenkinson, El Dorado Gantt, Covington HD Greers Ferry, Cleburne HD Amador, Amador HD Greeson, Pike HD Jennings, San Diego Guntersville, Marshall HD Antelope, Plumas Hamilton, Garland HD Kaweah, Tulare HD H. Neely Henry, Calhoun, St. HD Arrowhead, Crow Wing HD Lake of the Pines, Nevada Clair, Etowah Hinkle, Scott Barrett, San Diego Lewiston, Trinity Holt Reservoir, Tuscaloosa HD Maumelle, Pulaski HD Bear Reservoir, -

Changes in the Conditions of the Wabash River Drainage, 1990

2006 . Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 115(2) :156–169 CHANGES IN THE CONDITION OF THE WABASH RIVE R DRAINAGE FROM 1990-2004 Stacey L . Sobat, Charles C. Morris, and Alison K. Stephan : Biological Studie s Section, Indiana Department of Environmental Management, 100 North Senat e Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 US A Thomas P . Simon : U.S . Fish and Wildlife Service, 620 S . Walker Street, Bloomington, Indiana 47403 US A ABSTRACT . The Wabash River drainage was evaluated based on three hydrologic watershed units tha t were sampled from 1990–2004 so that patterns in biological integrity and assessment of aquatic lif e designated uses could be determined. The three units included : 1) the West Fork and lower White River, 2) the East Fork White River, and 3) the remainder of the Indiana portions of the Wabash River system above its confluence with the Ohio River . Targeted sampling was done in each of the three watershed units from 1990–1995, while a random probability sample design was used from 1996–2004 . Assessment of the fish assemblage information for the three periods showed increasing biological integrity for eac h of the three watersheds . The watershed with the highest biological integrity was the East Fork White River, followed by the West Fork White River, and Wabash River . Aquatic life designated uses were met in 76% of the East Fork White River stream miles ; 62% of the West Fork and lower White rivers ; and 53% of the Wabash River stream miles . Keywords : Biotic integrity, biological assessment, probabilistic design, Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI) The mandate of water quality monitorin g ten degrade the environment, resulting in a de- agencies is to assess the condition of the wa- tectable decline in biological integrity . -

Surname Given Name Book Name Page Maas Ida Fat Memoirs 50 Macarthur Douglas River City Memoirs 6 64 Maccaroni Jr. Home Mission 29 Maccaroni Mrs

Surname Given Name Book Name Page Maas Ida Fat Memoirs 50 MacArthur Douglas River City Memoirs 6 64 Maccaroni Jr. Home Mission 29 Maccaroni Mrs. Home Mission 29 Maccaroni P.P. Home Mission 27 MacDonald Al River City Memoirs 3 38 Mack Messr. River City Memoirs 2 106 Mack Mr. Age of Paper 28, 57 Mack Rev. River City Memoirs 5 69 Mack W.E. Age of Paper 25, 31, 45, 47, 49, 53, 57, 59, 62, 64 Mack Walter E. River City Memoirs 6 12 Mack Age of Paper 51, 57, 59, 63 Mack & Spencer Age of Paper 27, 28, 29, 31, 49, 51, 55, 57 Mack & Spencer River City Memoirs 5 33 Mack & Spencer Electric Light Co. Age of Paper 45, 49 Mack & Spencer Electric Light Plant Home Mission 50 Mackey Larry River City Memoirs 5 91 Mackinac Bridge River City Memoirs 5 112 Mackinac, Wisconsin River City Memoirs 5 8 MacKinnon Capt. Age of Paper 41 MacKinnon Duncan Age of Paper 42 MacKinnon F. Age of Paper 49, 69, 79, 98 MacKinnon F. River City Memoirs 1 21 MacKinnon F. River City Memoirs 2 92 MacKinnon F. River City Memoirs 6 94 MacKinnon Falkland Age of Paper 25, 41, 42, 43, 45, 47, 53, 64 MacKinnon Falkland (Picture) Age of Paper 40 MacKinnon Louise (Louie) King Age of Paper 43 MacKinnon Mrs. Age of Paper 43 MacKinnon William Age of Paper 42 MacKinnon Age of Paper 51, 55, 57, 59, 62, 63, 64, 73 MacKinnon F. River City Memoirs 3 74 MacKinnon Reggie Fat Memoirs 177 MacKinnon River City Memoirs 5 66 MacKinnon & Co. -

ED 125 882.. AUTROR in TITUTION PUB DATE Mervin, Ruth W; A

O DOCUMENT -RES aHE ED 125 882.. SE 020 429 AUTROR Mervin, Ruth W; TITLE A Guide to Ohio Outdoor Eduction Areas. Second Edition. r" INTITUTION Ohio Academy of Science, Columbs.;' Ohio State Dept, of Natural Resources, Columbus. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 238p.; Contains color-coded maps; olored photographs - :may tot reproduce well; For first ition of this publiCation, see ED 073 945 AVAILABLE FROM Ohio Department of Natural Resources,Division of Natural Areas and'Preserves, FountainSquare, Coluqbus, Ohio 42214 ($5.00), EDRS' PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$12.71,Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Directories; *Environmental Education; ield Trips; Guides; *Indexes (Locaters) ; Natural Resources; Nature Centers; *Outdoor Education; *Science Education;-Study.Facilities,: IDENTIFIERS *Ohio 't trESTRACT To. this new and updated second edition, eve 160 new sites and their description have been added. The firSt majosection,. outdoor educatiNn areas, includes state Parks, forests, ;and ildlife areas; historic sites andmemorials; Wayne National Forestl metropolitan county and city,parks; agency and private camps conservation agency properties; conservancy district lands aid reservoirs; school land laboratories; and private conservatiofarms and camp grounds. The second section is devoted to selected's ate, nature conservancy, university, and private 4ature preserves. In both sections, each outdoor area summar4,is arranged alphabeticall according to county and includes size and location, correct name, a short description, and the address of the person to contact fo -i-t use. Additional information concerning suitability for camping is given in chart form in the .4lrd sc.,,ctioni,-Seven color maps-des ribing Ohio geology, glacial deposits, soil regions, surface water, groundwater, original vegetation, and major forest types follow .,,AlsO included aro a sel'ected bibliography, and .index of sites, and directions for using this publication. -

Changes in the Condition of the Wabash Rive R Drainage from 1990-2004

2006 . Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 115(2) :156–169 CHANGES IN THE CONDITION OF THE WABASH RIVE R DRAINAGE FROM 1990-2004 Stacey L . Sobat, Charles C. Morris, and Alison K. Stephan : Biological Studie s Section, Indiana Department of Environmental Management, 100 North Senat e Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 US A Thomas P. Simon : U .S . Fish and Wildlife Service, 620 S . Walker Street , Bloomington, Indiana 47403 US A ABSTRACT . The Wabash River drainage was evaluated based on three hydrologic watershed units tha t were sampled from 1990–2004 so that patterns in biological integrity and assessment of aquatic lif e designated uses could be determined. The three units included : 1) the West Fork and lower White River , 2) the East Fork White River, and 3) the remainder of the Indiana portions of the Wabash River system above its confluence with the Ohio River . Targeted sampling was done in each of the three watershe d units from 1990–1995, while a random probability sample design was used from 1996–2004 . Assessment of the fish assemblage information for the three periods showed increasing biological integrity for eac h of the three watersheds . The watershed with the highest biological integrity was the East Fork White River, followed by the West Fork White River, and Wabash River . Aquatic life designated uses were met in 76% of the East Fork White River stream miles ; 62% of the West Fork and lower White rivers ; and 53% of the Wabash River stream miles . Keywords : Biotic integrity, biological assessment, probabilistic design, Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI) The mandate of water quality monitorin g ten degrade the environment, resulting in a de- agencies is to assess the condition of the wa- tectable decline in biological integrity .