How to Reduce Violence in Guerrero “Building Resilient Communities in Mexico: Civic Responses to Crime and Violence” Briefing Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

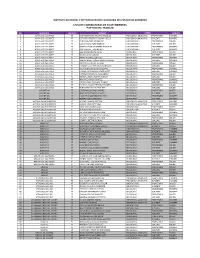

4. LISTA CANDIDATURAS PT.Xlsx

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO LISTA DE CANDIDATURAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS PARTIDO DEL TRABAJO NO. MUNICIPIO PARTIDO NOMBRE CARGO GÉNERO 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT IGOR ALEJANDRO AGUIRRE VAZQUEZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 2 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT OCTAVIO ROBERTO GALEANA BELLO PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL SUPLENTE HOMBRE 3 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT JENNY SANCHEZ RODRIGUEZ SINDICATURA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 4 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT KARLA PAOLA HARO MARCIAL SINDICATURA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 5 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT ROBERTO CARLOS ORTEGA GONZALEZ SINDICATURA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 6 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT JOSÉ MANUEL LEON BRUNO SINDICATURA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 7 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT ANA IRIS MENDOZA NAVA REGIDURIA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 8 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAYRA LEON CASIANO REGIDURIA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 9 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MARIO ALONSO QUEVEDO REGIDURIA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 10 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT SANTOS ANGEL TOMAS ANALCO RAMOS REGIDURIA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 11 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT LILIANA ESTEVEZ DE LA ROSA REGIDURIA 3 PROPIETARIA MUJER 12 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT DANELLY ESTEFANY ROMERO NAJERA REGIDURIA 3 SUPLENTE MUJER 13 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT REGINALDO LARREA BALTODANO REGIDURIA 4 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 14 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT CARLOS ALEJANDRO CHAVEZ LOPEZ REGIDURIA 4 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 15 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT DAYANA YIZEL NAVA AVELLANEDA REGIDURIA 5 PROPIETARIA MUJER 16 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAYRA LUCILA CADENA AGUILAR REGIDURIA 5 SUPLENTE MUJER 17 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAURICIO SUAZO BENITEZ REGIDURIA 6 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE -

Acuerdo 029/So/24-02-2021

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO ACUERDO 029/SO/24-02-2021 POR EL QUE SE DETERMINA EL NÚMERO DE SINDICATURAS Y REGIDURÍAS QUE HABRÁN DE INTEGRAR LOS AYUNTAMIENTOS DE LOS MUNICIPIOS DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, PARA EL PERIODO CONSTITUCIONAL COMPRENDIDO DEL 30 DE SEPTIEMBRE DEL 2021 AL 29 DE SEPTIEMBRE DEL 2024, TOMANDO COMO BASE LOS DATOS DEL CENSO DE POBLACIÓN Y VIVIENDA 2020 DEL INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA Y GEOGRAFÍA. ANTECEDENTES 1. El 14 de agosto de 2020, en la Cuarta Sesión Extraordinaria, el Consejo General del IEPC Guerrero, aprobó el Acuerdo 031/SE/14-08-2020, relativo al calendario del Proceso Electoral Ordinario de Gubernatura del Estado, Diputaciones Locales y Ayuntamientos 2020-2021. 2. El 31 de agosto de 2020, en la Octava Sesión Ordinaria el Consejo General del IEPC Guerrero, aprobó los Lineamientos para garantizar la integración paritaria del Congreso del Estado y Ayuntamientos, en el Proceso Electoral Ordinario de Gubernatura del Estado, Diputaciones locales y Ayuntamientos 2020-2021. 3. El 9 de septiembre de 2020, se declaró formalmente el inicio del Proceso Electoral Ordinario de Gubernatura del Estado, Diputaciones Locales y Ayuntamientos 2020-2021. 4. Mediante oficio número 739/2020 de fecha 17 de septiembre de 2020, el C. Pedro Pablo Martínez Ortiz, en su carácter de Secretario Ejecutivo del IEPC Guerrero, solicitó al Presidente del Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (en adelante INEGI), lo siguiente: “…solicito su amable apoyo y colaboración para que informe a esta autoridad electoral, la fecha en que se tendrán los resultados definitivos del número de población que habita en cada uno de los municipios del estado de Guerrero, conforme al Censo referido. -

Instituto Electoral Y De Participación Ciudadana Del Estado De Guerrero

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO ACUERDO 122/SE/24-04-2015 MEDIANTE EL QUE SE APRUEBA EL FINANCIAMIENTO PÚBLICO PARA GASTOS DE CAMPAÑA QUE CORRESPONDE A LOS CANDIDATOS INDEPENDIENTES DE LOS MUNICIPIOS DE AHUACUOTZINGO, CUETZALA DEL PROGRESO Y PEDRO ASCENCIO ALQUISIRAS, GUERRERO, EN EL PROCESO ELECTORAL 2014-2015. A N T E C E D E N T E S 1. El veintiséis de noviembre del año dos mil catorce, en Sesión Extraordinaria del Consejo General del Instituto Electoral y de Participación Ciudadana del Estado de Guerrero, se aprobó por unanimidad de votos, el Acuerdo 043/SE/26-11-2014, por el que se emitió la convocatoria, el número de ciudadanos requeridos para obtener el porcentaje de apoyo ciudadano, el tope de gastos para recabar el apoyo ciudadano, el modelo único de estatutos y los formatos que deberán utilizar los ciudadanos interesados en postularse como candidatos independientes en el Proceso Electoral Ordinario de Gobernador, Diputados y Ayuntamientos 2014-2015. 2. El treinta de diciembre del año dos mil catorce, en Sesión Extraordinaria, el Consejo General del Instituto Electoral y de Participación Ciudadana del Estado de Guerrero, aprobó por unanimidad de votos, el Acuerdo 052/SE/30-12-2014 mediante el cual se modificó el anexo número 3, del Acuerdo 043/26-11-2014, relativo al número de ciudadanos requeridos para obtener el porcentaje de apoyo ciudadano de los interesados en postularse como candidatos independientes, en el Proceso Electoral ordinario de Gobernador, Diputados y Ayuntamientos 2014-2015. 3. El quince de enero de dos mil quince, el Consejo General del Instituto Electoral y de Participación Ciudadana del Estado de Guerrero aprobó, en Sesión Ordinaria, el Acuerdo 002/SO/15-01-2015 relativo al financiamiento público para el año 2015 que corresponde a los partidos políticos para actividades ordinarias permanentes, para gastos de campaña y para actividades específicas, así como el financiamiento público a candidatos independientes. -

Trabajadores Con Doble Asignación Salarial En Municipios No Colindantes Geográficamente Fondo De Aportaciones Para La

Formato: Trabajadores con Doble Asignación Salarial en Municipios no Colindantes Geográficamente Fondo de Aportaciones para la Educación Básica y Normal (FAEB) 1er Trimestre 2013 Clave Presupuestal Periodo en el CT Entidad Federativa Municipio Localidad RFC CURP Nombre del Trabajador Clave integrada Clave de Clave de Sub Clave de Horas semana Clave CT Nombre CT Partida Presupuestal Código de Pago Número de Plaza Desde Hasta Unidad Unidad Categoría mes 12 IGUALA DE LA INDEPENDENCIA IGUALA DE LA INDEPENDENCIA AADO78080486A AADO780804HGRBZR02 ORLANDO ABAD DIAZ 07600300.0 E1587001372 1103 7 60 3 E1587 0 1372 12DBA0028E JOSE MA MORELOS Y PAVON 20130115 20130330 12 PILCAYA EL PLATANAR AADO78080486A AADO780804MGRBZR00 ABAD DIAZ ORLANDO 0002007207P0TS2040300.0013033 20 7 20 7P 0TS20403 0 13033 12ETV0008S JOSE MA. MORELOS Y PAVON 20130115 20130330 12 TIXTLA DE GUERRERO ZOQUIAPA AAMA781215317 AAMA781215HGRBRR00 JOSE ARTURO ABRAJAN MORALES 07120300.0 E0281810561 1103 7 12 3 E0281 0 810561 12DPR0280B JUAN N ALVAREZ 20130115 20130330 12 GENERAL HELIODORO CASTILLO EL NARANJO AAMA781215317 AAMA781215HGRBRR00 ABRAJAN MORALES JOSE ARTURO 000200720740PR2030300.0008251 20 7 20 74 0PR20303 0 8251 12DPR2341M VICENTE GUERRERO 20130115 20130330 12 QUECHULTENANGO QUECHULTENANGO AANK850905U83 AANK850905MGRLXR00 KARLA LISELY ALMAZAN NUNEZ 07663700.0 E0687121265 1103 7 66 37 E0687 0 121265 12DML0049C CENTRO DE ATENCION MULTIPLE NO. 49 20130115 20130330 12 CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO AANK850905U83 AANK850905MGRLXR00 KARLA LISELY ALMAZAN NUNEZ -

Sistemas De Riego En La Cañada De Huamuxtitlán: Tradición Y Actualidad

Sistemas de riego en la Cañada de Huamuxtitlán: tradición y actualidad • América Rodríguez-Herrera • Berenise Hernández-Rodríguez • Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, México • Jacinta Palerm-Viqueira • Colegio de Postgraduados, México Resumen En este artículo se discute la importancia del uso de la tecnología tradicional en sistemas de riego caracterizados por un entorno ecológico vulnerable, con enfoque en la descripción de su infraestructura: trompezones o protección ribereña, bocatomas y canales, con la intención de contribuir a la reflexión sobre su pertinencia; se pretende también tender un puente hacia una discusión necesaria: la búsqueda de opciones de desarrollo y sustentabilidad, a partir de experiencias productivas con una efectividad probada y arraigada a una cultura ancestral. Palabras clave: irrigación, técnica tradicional, sustentabilidad, trompezones, enlamar, bocatomas. 75 Introducción las tecnologías tradicionales lo que ha llevado al estancamiento de los sistemas económicos En agosto de 2009, en una reunión convocada campesinos, por constituir una barrera para por la Comisión Nacional del Agua (Conagua) y su desarrollo y modernización. Más aún, la los ayuntamientos de Alpoyeca y Huamuxtitlán, pobreza sería resultado de la escasez de capital Guerrero, México, se informó a los comisarios y de la falta de habilidades tecnológicas. Todo y comisariados de las comunidades de la ello ha propiciado políticas hacia el sector rural Cañada (Guerrero), el impulso del proyecto orientadas a la transferencia de estos factores “Modernización -

Conflictos Agrarios Por Límites En La Región De La Montaña, 2003

SITUACIÓN AGRARIA Cuadro 33. Conflictos agrarios por límites en la región de la Montaña, 2003. La Montaña de Guerrero es la región que concentra el mayor número de población indígena en la entidad. La ausencia en la definición de límites y posesión de la tierra constituye el principal factor de los conflictos en la región. Este cuadro muestra un listado de los principales conflictos agrarios que para 2003 se encontraban sin solución. En la información se incorpora un indicador sobre el nivel de riesgo que implica cada uno de estos problemas agrarios. En algunos casos se ha llegado al enfrentamiento directo entre los habitantes de las partes en disputa. La ubicación de las contrapartes ejemplifica que estas problemáticas rebasan los límites del estado de Guerrero. Cuadro 33 (continuación). Municipio Núcleo agrario Contraparte Problemática Nivel de riesgo Acatepec Acatepec Zapotitlán Tablas 1 700 hectáreas. Alto Atlixtac Huitzapula Coapala 2 400 hectáreas Alto Tlapa Ahuatepec Ejido Ahuatepec comunidad 185 hectáreas Medio Malinaltepec Arroyo San Pedro Tilapa Inconformidad del anexo Arroyo San Pedro Medio Metlatónoc Cochoapa el Grande Huexoapa o Huexuapan Cochoapa posee una superficie de Huexoapa Medio Ahuacuotzingo Xitopontla Pequeños propietarios “Invasión” gradual de gente de Xitopontla hacia Alto tierras de los pequeños propietarios Malinaltepec Coatzoquitengo Alacatlatzala Por posesión de tierras Alto Cuadro 33 (continuación). Municipio Núcleo agrario Contraparte Problemática Nivel de riesgo Huamuxtitlán Jilotepec Acaxtlahuacan, Puebla Por límites Medio Tlacoapa Tlacoapa Ocoapa Por límites Medio Atlamajalcingo Atlamajalcingo del Monte Quiahuitlatzala Por posesión de tierra Medio del Monte Atlamajalcingo Zilacayotitlán Atlamajalcingo del Monte Por límites y por posesión de la tierra Bajo del Monte Malinaltepec Malinaltepec Alacatlatzala Por posesión de la tierra Medio Alcozauca Ixcuinatoyac Santiago Petlacala, Oaxaca 200 Medio Alcozauca Tlahuapa San Martín Peras, Oaxaca 600 Alto Cuadro 33 (continuación). -

Directorio De Oficialías Del Registro Civil

DIRECTORIO DE OFICIALÍAS DEL REGISTRO CIVIL DATOS DE UBICACIÓN Y CONTACTO ESTATUS DE FUNCIONAMIENTO POR EMERGENCIA COVID19 CLAVE DE CONSEC. MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE OFICIALÍA NOMBRE DE OFICIAL En caso de ABIERTA o PARCIAL OFICIALÍA DIRECCIÓN HORARIO TELÉFONO (S) DE CONTACTO CORREO (S) ELECTRÓNICO ABIERTA PARCIAL CERRADA Días de atención Horarios de atención 1 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ ACAPULCO 1 ACAPULCO 09:00-15:00 SI CERRADA CERRADA LUNES, MIÉRCOLES Y LUNES-MIERCOLES Y VIERNES 9:00-3:00 2 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ TEXCA 2 TEXCA FLORI GARCIA LOZANO CONOCIDO (COMISARIA MUNICIPAL) 09:00-15:00 CELULAR: 74 42 67 33 25 [email protected] SI VIERNES. MARTES Y JUEVES 10:00- MARTES Y JUEVES 02:00 OFICINA: 01 744 43 153 25 TELEFONO: 3 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ HUAMUCHITOS 3 HUAMUCHITOS C. ROBERTO LORENZO JACINTO. CONOCIDO 09:00-15:00 SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-05:00 01 744 43 1 17 84. CALLE: INDEPENDENCIA S/N, COL. CENTRO, KILOMETRO CELULAR: 74 45 05 52 52 TELEFONO: 01 4 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ KILOMETRO 30 4 KILOMETRO 30 LIC. ROSA MARTHA OSORIO TORRES. 09:00-15:00 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-04:00 TREINTA 744 44 2 00 75 CELULAR: 74 41 35 71 39. TELEFONO: 5 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PUERTO MARQUEZ 5 PUERTO MARQUEZ LIC. SELENE SALINAS PEREZ. AV. MIGUEL ALEMAN, S/N. 09:00-15:00 01 744 43 3 76 53 COMISARIA: 74 41 35 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-02:00 71 39. 6 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PLAN DE LOS AMATES 6 PLAN DE LOS AMATES C. -

The Market As Generator of Urban Form: Self-Help Policy for the Civic Realm IRMA RAMIREZ California State Polytechnic University Pomona

THE MARKET AS GENERATOR OF URBAN FORM 119 The Market as Generator of Urban Form: Self-Help Policy for the Civic Realm IRMA RAMIREZ California State Polytechnic University Pomona “It is impossible to imagine beings more function fluidly within the dynamics of its own inner whimsical or haphazard than the streets setting. In fact the “chaotic” often functions to es- of Taxco. They hate the mathematical fi- tablish the dynamics and functional mechanisms of delity of straight lines; they detest the lack a city. On the other hand, while a structured “scien- of spirit of anything horizontal…they sud- tific” approach, such as the grid, is an organizing denly rear up a ravine, or return repentfully regulator for cities; it does not methodically contrib- to where they started. Who said streets ute to fluidly functional and culturally rich civic sys- were invented to go from on place to an- tems. Both chaos and rigid order can work to create other, or to provide access to houses? [In both, places rich with social dynamics and places Taxco] they are irrational entities…like ser- lifeless and empty. The evolution of cities occurs pents stuffed with silver coiled around a through a combination of factors acting together ei- bloated abdomen: yet they relinquish, lan- ther spontaneously or in a planned manner, but al- guidly swoon, and disappear into the hill- ways within a unique context. side. Later they invent pretense for resuming, not where they’re supposed to, The expressions of life in the city however, chal- but in the place that suits the indolence. -

Huitzuco De Los Figueroa Guerrero

NBaQ % ' m % ■81 V £--: S|l||||®i::i ■ ■ -I e«. ¡I mm m #00 « .. ## ■ ■'ir/'-' # %6 É# t-L t , / \ mm mm * "¿I Ww#m#N ^8# i : ' mm# i V,.í ■ - m # #1 ,iv' ma GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE H. AYUNTAMIENTO CONSTITUCIONAL DE INSTITUTO NftCIONM. DC €STW)»STICR HUI7ZUC0DE losfigueroa SfOGRRf» C INFORMATICA — r Huitzuco dft los Figueroa. Estado de Guerrero. Cuaderno Estadístico Municipal. Publicación única. Primera edición. 180 p.p. Aspectos Geográficos, Estado y Movimiento de la Población, Vivienda e Infraestructura Básica para los Asentamientos Humanos, Salud, Educación, Seguridad y Orden Público, Empleo y Relaciones Laborales, Información Económica Agregada, Agricultura, Gana- dería, Silvicultura, Industria, Comercio, Transporte y Comunicaciones, Servicios Financieros y Finanzas Públicas. OBRAS AFINES O COMPLEMENTARIAS SOBRE EL TEMA: Anuarios Estadísticos de los Estados. SI REQUIERE INFORMACIÓN MÁS DETALLADA DE ESTA OBRA, FAVOR DE COMUNICARSE A: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática Dirección General de Difusión Dirección de Atención a Usuarios y Comercialización Av. Héroe de Nacozari Núm. 2301 Sur Fracc. Jardines del Parque, CP 20270 Aguascalientes, Ags. México TELÉFONOS: 01 800 674 63 44 Y (449) 918 19 48 www.inegi.gob.mx atención.usuarios® inegi.gob.mx \ / DR © 2002, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática Edificio Sede Av. Héroe de Nacozari Núm. 2301 Sur Fracc. Jardines del Parque, CP 20270 Aguascalientes, Ags. www.inegi.gob.mx atención.usuarios® inegi.gob.mx Huitzuco de los Figueroa Estado de Guerrero Cuaderno Estadístico Municipal Edición 2001 Impreso en México ISBN 970-13-4003-5 Presentación El Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI) y el H. -

Estructura Funcional De Las Localidades Urbanas De Municipios Costeros De Guerrero

Estructura funcional de las localidades urbanas de municipios costeros de Guerrero Lilia Susana Padilla y Sotelo* Recibido: junio 18, 1998 ,'- Aceptado en versión final: octubre 23, 1998 Resumen. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar la estructura funcional de cuatro ciudades iocalizadas en municipios costeros de Guerrero (Acapulco. Zihuatanejo. Tecpan y Petatián), que reúnen a más de una quinta parte de la población estatal. Se tomaran en cuenta las distintas funciones económicas que ahí tienen efecto. examinadas mediante métodos detipificación y técnicas de análisis demográfico: para ello, se considera el grado de urbanización de esos municipios y la estructura de su PEA. Como resultado de la investigación, se presenta una clasificación de la base económica de esas ciudades Palabras clave: municipios costeros. tipologia urbana, Guerrero. Abslracl Thfs papel exam nec lne lunci ona str.cluie of foLr cqasia c 1 es " lne siate of GJcrrero iAcaputco Zindatanelo Tecpan ana Peiatlan,. v.nere o.er one-fiHn of tne lola slale pop.lalon .e ronaoa,s Ine economic f~ictonof rnese urDan Dlaces Mas measured by different methods and techniques of demographic analysis, considering the degree of urbanisation in each of the municipios containing these cities and the structure of the economically active population As a result of this, an urban typoiogy of these cities based on the structure of the local economy, is presented. Key words: coastai municipios, urban typology, Guerrero. INTRODUCCIÓN representativo de los estudios geográficos, ya que los recursos humanos y materiales que El estudio forma parte de un proyecto sobre la existen . en un espacio se relacionan dinámica poblacional de la zona costera de directamente con aquéllas. -

El Contenido De Este Archivo No Podrá Ser Alterado O

EL CONTENIDO DE ESTE ARCHIVO NO PODRÁ SER ALTERADO O MODIFICADO TOTAL O PARCIALMENTE, TODA VEZ QUE PUEDE CONSTITUIR EL DELITO DE FALSIFICACIÓN DE DOCUMENTOS DE CONFORMIDAD CON EL ARTÍCULO 244, FRACCIÓN III DEL CÓDIGO PENAL FEDERAL, QUE PUEDE DAR LUGAR A UNA SANCIÓN DE PENA PRIVATIVA DE LA LIBERTAD DE SEIS MESES A CINCO AÑOS Y DE CIENTO OCHENTA A TRESCIENTOS SESENTA DÍAS MULTA. DIRECION GENERAL DE IMPACTO Y RIESGO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD REGIONAL, DEL PROYECTO: CAMINO TLACOTEPEC - ACATLÁN DEL RIO, TRAMO: DEL KM. 5+000 AL KM. 10+000, MUNICIPIO DE GRAL. HELIODORO CASTILLO, ESTADO DE GUERRERO. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes Centro Guerrero (SCT). Dr. Gabriel Leyva Alarcón sin número Burócrata Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero C.P. 39090. Tel. 01 (747) 116-2742. Noviembre del 2019. ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL DEL CAMINO TLACOTEPEC - ACATLÁN DEL RIO, TRAMO: DEL KM. 5+000 AL KM. 10+000, MUNICIPIO DE GRAL. HELIODORO CASTILLO, ESTADO DE GUERRERO. Contenido I. DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL 3 I.1 Datos generales del proyecto 3 1.1.1. Nombre del proyecto 3 I.1.2 Ubicación del proyecto. 3 1.1.3 Duración del proyecto. 12 I.2 Datos generales del Promovente 13 I.2.1 Nombre o razón social 13 I.2.2 Registro Federal de Contribuyentes del promovente 13 I.2.3 Nombre y cargo del representante legal 13 I.2.4 Dirección del promovente o de su representante legal 13 I.2.5 Nombre del consultor que elaboró el estudio. 13 I.2.6 Nombre del responsable técnico de la elaboración del estudio 13 I.2.7 Registro Federal de Contribuyentes o CURP 13 I.2.8 Dirección del responsable técnico del estudio 13 II. -

A Sleeping Giant Stirs: Mexico'S

A Sleeping Giant Stirs: Mexico's October Risings Largely downplayed in the U.S. media, ground-shaking events are rattling Mexico. On one key front, Mexican Interior Minister Miguel Angel Osorio Chong announced October 3 the Pena Nieto administration’s acceptance of many of the demands issued by striking students of the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN). IPN Director Yoloxichitl Bustamante, whose ouster had been demanded by the students, handed in her resignation. Osorio Chong’s words were delivered to thousands of students from an improvised stage outside Interior Ministry headquarters in Mexico City. In addition to Bustamante’s departure, the senior Pena Nieto cabinet official pledged greater resources for the IPN, the cancellation of administrative and academic changes opposed by the students, the prohibition of lifetime pensions for IPN directors, the replacement of a much-criticized campus police force, and no retaliations against the strikers. Osorio Chong shared the students’ concerns that IPN policies were turning a professional education into an assembly-line diploma mill and reducing “the excellence of schools of higher education.” Education Secretary Emilio Chuayfett was noticeably absent for Osorio Chong’s presentation, which was held at the conclusion of a Friday afternoon march through the Mexican capital that attracted in upwards of 20,000 students. Distrustful of the government, the students are reacting cautiously to the Pena Nieto administration’s response to their 10-point petition, insisting among other things that Yolo Bustamante be held accountable for alleged transgressions before leaving her job. Student activists said that acceptance of the government’s response will be democratically debated and resolved at upcoming meetings of the 44 schools that form the IPN.