071728809 [2007] RRTA 324 (19 December 2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CDRO) for Copies: Dr

COORDINATION OF DEMOCRATIC RIGHTS ORGANISATIONS CONSTITUENTS: 1. Asansol Civil Rights Association, West Bengal 2. Association for Democratic Rights (AFDR), Punjab 3. Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR), West Bengal 4. Bandi Mukti Committee, (BMC), West Bengal 5. Campaign for Peace & Democracy, (CPDM), Manipur 6. Civil Liberties Committee (CLC), Andhra Pradesh 7. Civil Liberties Committee,(CLC),Telengana 8. Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights (CPDR), Maharastra 9. Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights(CPDR),Tamilnadu 10. Coordination for Human Rights (COHR), Manipur 11. Jharkhand Council for Democratic Rights(JCDR) 12. Manab Adhikar Sangram Samiti (MASS), Assam 13. Naga Peoples Movement for Human Rights (NPMHR) 14. Organisation for Protection of Democratic Rights (OPDR), Andhra Pradesh 15. Peoples Committee for Human Rights (PCHR), Jammu and Kashmir 16. Peoples Democratic Forum (PDF), Karnataka 17. Peoples Union For Democratic Rights (PUDR), Delhi 18. Peoples Union for Human Rights(PUHR),Haryana Coordination for Democratic Rights Organisations Published by Peoples Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) on behalf of CDRO (CDRO) For Copies: Dr. Moushumi Basu, A-6/1, Aditi Apartments, D Block, Janakpuri, New Delhi: 110058 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.pudr.org April 2017 Suggested Contribution: Rs. 15/- Release Political Prisoners! “When they became criminal, they invented justice and prescribed whole codices for themselves in order to maintain it, and to ensure the codices they set up the guillotine.” — Fydor Dostevesky, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man “If you want to establish some conception of a society, go find out who is in gaol.” — John Dewey “Those who are arrested for attempting to change conditions of injustice are not merely the prisoners of the state, but of their own conscience. -

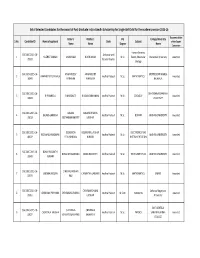

PG IG SGC-2015-16-Website Selection.Xlsx

list of Selected Candidates for the award of Post Graduate Indira Gandhi Scholarship for Single Girl Child for the academic session 2015-16 Father's Mother's PG College/University Recommedation S.No. Candidate ID Name of applicant State Subject of the Expert Name Name Degree Name Committee Human Genetics SGC-OBC-2015-16- Andaman and 1 NUZHAT UMRAN UMRAN ALI NOOR JAHAN M.Sc. & Molecular Bharathiar University Awarded 39593 Nicobar Islands Biology SGC-GEN-2015-16- ANAPAREDDY ANAPAREDDY MONTESSORI MAHILA 2 ANAPAREDDY SYAMALA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. MATHEMATICS Awarded 30849 RATHAIAH AKKAMMA KALASALA SGC-OBC-2015-16- SRI KRISHNADEVARAYA 3 B PRAMEELA B MADDILETI B ADILAKSHMAMMA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. ZOOLOGY Awarded 34803 UNIVERSITY SGC-OBC-2015-16- BALAKA BALAKA BHAGYA 4 BALAKA SARANYA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. BOTANY ANDHRA UNIVERSITY Awarded 35010 SEETHARAMAMURTY LAKSHMI SGC-OBC-2015-16- BEZAWADA BEZAWADA LAKSHMI ELECTRONICS AND 5 BEZAWADA MADHAVI Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. ANDHRA UNIVERSITY Awarded 40632 YEDUKONDALU KUMARI INSTRUMENTATION SGC-OBC-2015-16- BONU PRASANTHI 6 BONU APPALANAIDU BONU PARVATHI Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. TECH GEOPHYSICS ANDHRA UNIVERSITY Awarded 35949 KUMARI SGC-OBC-2015-16- C MURALI MOHAN 7 CHENNA MOUNA C ANANTHA LAKSHMI Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. MATHEMATICS SPMVV Awarded 31979 RAO SGC-OBC-2015-16- CHENNAM DHANA Acharya Nagarjuna 8 CHENNAM PRIYANKA CHENNAM SURIBABU Andhra Pradesh M.Com. commerce Awarded 31461 LAKSHMI University SMT.GENTELA SGC-OBC-2015-16- CHEVIRALA CHEVIRALA 9 CHEVIRALA ANUSHA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. PHYSICS SAKUNTALAMMA Awarded 32027 VENKATESWARARAO KALAVATHI COLLEGE Chaitanya SGC-OBC-2015-16- CHIRUMALLA 10 CHIRUMALLA HARITHA SAROJANA Andhra Pradesh M.Sc. -

Chapter 8 -- Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Chapter 8 FOREIGN TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS◊ Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Ansar al-Sunna (AS) Armed Islamic Group (GIA) Asbat al-Ansar Aum Shinrikyo (Aum) Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA) Gama’a al-Islamiyya (IG) HAMAS Harakat ul-Mujahedin (HUM) Hizballah Islamic Jihad Group (IJU) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya Organization (JI) Al-Jihad (AJ) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kongra-Gel (KGK) Lashkar e-Tayyiba (LT) Lashkar i Jhangvi (LJ) Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM) Mujahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK) National Liberation Army (ELN) Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC) Al-Qaida (AQ) Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) Real IRA (RIRA) Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) ◊ FTO aliases cited are consistent with the Specially Designated Nationals list maintained by the Department of Treasury. The full list can be found at the following website: http://www.treasury.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac/sdn/sdnlist.txt . 183 Revolutionary Nuclei (RN) Revolutionary Organization 17 November Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) Shining Path (SL) United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) __________________________________ Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) a.k.a. Arab Revolutionary Brigades; Arab Revolutionary Council; Black September; Fatah Revolutionary Council; Revolutionary Organization of Socialist Muslims Description The ANO international terrorist organization was founded by Sabri al-Banna (a.k.a. -

(In Rs.) Proposed Da

S. No. First Name Father/Husband First Name Address State PINCode Folio Number of Amount Proposed Date of Securities Due transfer to IEPF (in Rs.) (DD-MON-YYYY) 29-Sep-2022 1 SURINDER SINGH ANAND S SANT SINGH MS C3 JNLEY LAL APARTMENTS PRITAMPORE DELHI Delhi 110034 JKB046977 29400 29-Sep-2022 2 JASWANT SINGH KOTWAL X SO S R KOTWAL PIRMITHA BAZAR JAMMU JK Jammu and Kashmir 180001 JKB001498 55125 29-Sep-2022 3 BUSHAN LAL RAINA Late Sh Niranjan Nath Raina H No 323 N Durga Nagar Sector 2 BPO Roop Nagar Jammu Jammu and Kashmir 180013 IN30234910101769 35133 29-Sep-2022 4 TARIQ KATHWARI GHULAM MOHAMMED KATHWARI KATHWARI RUGS INTERNATIONAL RESIDENCY ROAD SRINAGAR KASHMIR Jammu and Kashmir 190001 IN30234910339898 32865 29-Sep-2022 5 SHEIKH NAZIR AHMAD X 10 M A ROAD SRINAGAR JK Jammu and Kashmir 190001 JKB001377 31500 29-Sep-2022 6 MOHD IQBAL DALAL Mohd Maqbol Dalal K M Trading Co Court Road Amira Kadal Srinagar Jammu and Kashmir 190002 IN30234910083672 29400 29-Sep-2022 7 GHULAM MOHAMAD Abdul Ahad Tali 1 Khanpora Baramulla Kasmir Jammu and Kashmir 193101 IN30234910110992 55440 29-Sep-2022 8 ASHIT S JAIN SAREMAL 138 V P ROAD SICKA NAGAR E/12 3RD FLOOR MUMBAI Maharashtra 400004 JKB052942 63000 29-Sep-2022 9 VIKRAM SHARMA BHASKAR CHANDER H Q 36 INF BDE C/O 56 APO Maharashtra JKB020465 2100 29-Sep-2022 10 HAJRA BANOO ABDUL SAMAD KHOSA DO ABDUL SAMAO KHOSA Jammu and Kashmir JKB025675 2100 29-Sep-2022 11 ASHIQ HUSSAIN BUCH BASHIR AHMAD BUCHH S/O LATE BASHIR AHMED BUCH R/Q HOUSE NO 12 LANE NO 2 S A COL NOWHAM BYE PASSJammu BUDGAM and Kashmir KASHMIR JKB058294 -

Awarded MNAMS in the Year 2018: (PDF File)

List of Members Awarded MNAMS – 2018 Who have passed the Diplomate of National Board (DNB) Examination of National Board of Examinations (NBE) S.No. Name & Address of Candidate Category Year of Passing MNAMS Award Date 1. Dr. Indhu Kannan Pathology December, 2016 25th July, 2018 11-1/306, Madurai Theni Road, Palaniammal Childrens Hospital, Andipatti, Theni, Tamil Nadu-625512. 2. Dr. Karthikeyan V S Radiodiagnosis December, 2016 25th July, 2018 Palaniammal Children’s Hospital, No.11-1/306, Madurai Theni Road, Aundipatty – 625512, Theni Road, (Tamil Nadu). 3. Dr. Manujesh Bandyopadhyay Cardio Thoracic December, 2015 25th July, 2018 Mainadanga (West), Surgery Chinsurah, Hooghly – 712102, West Bengal. 4. Dr. Rashmi Tiwari Psychiatry June, 2016 25th July, 2018 160 Income Tax Housing Society, Vinayak Pur, Kanpur – 208024. 5. Dr. N Vasanthi General Medicine October, 2007 25th July, 2018 Department of General Medicine, ‘E’ Quarters, 3rd Floor, Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalapet, Kanagachetti Kulam Puducherry – 605014. 6. Dr. Tim Thomas Joseph Anaesthesiology December, 2012 25th July, 2018 QTS No.106, KMC Campus, Manipal – 576104. 7. Dr. Unnikuttan D Orthopaedics December, 2016 25th July, 2018 Puthumana, Puthiyavila P.O., Alappuzha (D), Kerala – 690531. 8. Dr. Hena Rani Microbiology July, 2008 25th July, 2018 A-4/147, Paschim Vihar, New Delhi – 110063. 9. Dr. Nandan Kumar Mishra Orthopaedics December, 2016 25th July, 2018 House No.303, Block No.13, Sector 1, Khelgaon Housing Complex, PO – Hotwar, Ranchi, Jharkhand – 835217. 10. Dr. Ahirrao Atul Atmaram General Medicine June, 2011 25th July, 2018 “AAI” Bunglow, In Front of Shivkalp Residency, Shanti Nagar (Ram Krishna Hari Nagar), Makhamalabad Road, Nashik – 422003. -

India – IND33994 – Naxalites – Tamil Nadu – Communist Party of India

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND33994 Country: India Date: 2 December 2008 Keywords: India – IND33994 – Naxalites – Tamil Nadu – Communist Party of India – Maoist – CPI-Maoist – Communist Party of India Marxist-Leninist/People’s War – People’s War Group – Maoist Communist Centre of India – People’s Watch This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide a brief history of the CPI (Maoist) party, including its antecedents, links with militant activities, and accusations of links to terrorism. 2. Please also provide a brief history of the party’s youth wing, the Radical Youth league. 3. What is the background of the “Peoples Watch” organisation (www.pwtn.org) in Madurai; is it an independent NGO, or a publicity vehicle for a particular party? 4. Deleted. 5. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide a brief history of the CPI (Maoist) party, including its antecedents, links with militant activities, and accusations of links to terrorism. Information was located to indicate that the Communist Party of India-Maoist, or CPI- Maoist, was formed in September 2004, the product of the merger of the Communist Party of India (Marxist Leninist)/People’s War (also known as the People’s War Group or PWG), and the Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCC) (‘Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI- Maoist)’ (Undated), South Asia Terrorism Portal http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/maoist/terrorist_outfits/CPI_M.htm – Accessed 18 November 2008 – Attachment 1). -

Maoist Movement in India (N.T.Ravindranath) Dated: 29-12-2015

Maoist Movement in India (N.T.Ravindranath) Dated: 29-12-2015 The Naxalite movement in the country originated in 1967 from a small village called Naxalbari in Darjeeling district of West Bengal. It started as a peasant uprising which erupted on May 25, 1967. This violent movement was led by Charu Mazumdar and Kanu Sanyal, two radical CPI-M activists, who were influenced by the revolutionary thoughts and teachings of Chinese communist leader Mao Tse Tung. Though the leftist government of West Bengal was able to suppress this movement with brutal force, this violent peasant uprising soon caught the fancy of many leftist intellectuals and young radicals in different parts of the country, leading to the formation of a number of small groups of left-extremists in different states who supported the violent path adopted by Charu Mazumdar in protecting the rights of poor peasants in Naxalbari. All these groups preached and justified violent means to ensure justice to the millions of poor, oppressed and exploited sections of people in India. Since the violent peasant uprising in Naxalbari had given the inspiration for the launch of the different left-extremist groups in India, all these groups came to be known as Naxal groups and their supporters are called Naxalites. With the upsurge of Naxalism, the Naxal groups from different states like Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Orissa and West Bengal came under a common platform under the leadership of Charu Mazmdar and set up the All India Coordination Committee of Revolutionaries (AICCR) on November 12, 1967. It was renamed later as the All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR). -

(Maoist) Central Committee Is Appealing to All Democratic

to new areas, consolidated party, PLGA, politically and militarily, consolidated the existing Revolutionary People’s Committees/Janatana Sarkars and expanded them in newer areas. All these successes had won us the support of many revolutionary forces, intellectuals, democrats, progressive and patriotic forces. Comrades! Our losses had been very severe. Unless each committee from the CC to the lower committees and the entire party strives very hard to build up new forces in a planned manner on a wide scale and continues the rectification campaign effectively we will not be able to fulfill the losses incurred, particularly that of Com. Azad and other leadership comrades at central and state level. Only when we understand the real reasons behind the losses, we can prevent them and only then we can strengthen the party as an impregnable fort to the enemy. To identify the real reasons we have to take lessons from the experiences of our party and Maoist parties of other countries. We have to expand and intensify the self-defensive war waged under the party’s leadership by PLGA, people and by uniting with all struggling forces of our country and other countries. If we firmly rely on the masses and make use of our PLGA properly in the war, we would definitely be able to defeat Green Hunt. Let us prepare ourselves to wage people’s war with utmost courage and determination. Celebrate the 6th anniversary of our party formation Press Releases of day with brimming revolutionary enthusiasm and zeal. Let us propagate widely the successes won even amidst severe repression in the past one COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MAOIST) year.