Apophatic Measures: Toward a Theology of Irreducible Particularity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquired Contemplation Full

THE ART OF ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION FOR EVERYONE (Into the Mystery of God) Deacon Dr. Bob McDonald ECCE HOMO Behold the Man Behold the Man-God Behold His holy face Creased with sadness and pain. His head shrouded and shredded with thorns The atrocious crown for the King of Kings Scourged and torn with forty lashes Humiliated and mockingly adored. Pleading with love rejected Impaled by my crucifying sins Yet persisting in his love for me I see all this in his tortured eyes. So, grant me the grace to love you As you have loved me That I may lay down my life in joy As you have joyfully laid down your life for me. In the stillness I seek you In the silence I find you In the quiet I listen For the music of God. THE ART OF ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION Chapter 1 What is Acquired Contemplation? Chapter 2 The Christian Tradition Chapter 3 The Scriptural Foundation Chapter 4 The Method Chapter 5 Expectations Chapter 6 The Last Word CHAPTER 1 WHAT IS ACQUIRED CONTEMPLATION? It will no doubt come as a surprise For the reader to be told that acquired contemplation is indeed somethinG that can be “acquired” and that it is in Fact available to all Christians in all walKs oF liFe. It is not, as is commonly held, an esoteric practice reserved For men and women oF exceptional holiness. It is now Known to possess a universal potential which all oF us can enjoy and which has been larGely untapped by lay Christians For niGh on 2000 years. -

Christ and Analogy the Christocentric Metaphysics of Hans Urs Von Balthasar by Junius Johnson

Christ and Analogy The Christocentric Metaphysics of Hans Urs von Balthasar by Junius Johnson This in-depth study of Hans Urs von Balthasar’s metaphysics attempts to reproduce the core philosophical commitments of the Balthasarian system as necessary for a deep understanding of von Balthasar’s theology. Focusing on the God-world relation, the author examines von Balthasar’s reasons for rejecting all views that consider this relation in terms of either identity or pure difference, and makes clear what is at stake in these fundamentally theological choices. The author then details von Balthasar’s understanding of the accepted way of parsing this relationship, analogy. The philosophical dimensions of analogy are explored in such philosophical topics as the Trinity and Christology, though these topics may be treated only in a preliminary way in a study focused on metaphysics. “Crisp writing, clear thought, insightful reflection on a seminal and influential thinker's take on one of the most fundamental themes of theology–what more would you want from a book in theology? This is in fact what you get with Johnson's Christ and Analogy. Whether you are interested in von Balthasar, in theological method, or in relationship between metaphysics and theology you should read this book.” --Miroslav Volf, Yale Divinity School Junius Johnson is a lecturer at Yale Divinity School and a research fellow at the Rivendell Institute at Yale University. Johnson earned a Ph.D. in theology at Yale University. Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction I. Theology’s Handmaid: Scope of the Project A. What is Metaphysics? B. -

The Need to Believe in Life After Death Questions About Islam?

“To the righteous soul will be said: O (thou) soul, in In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful (complete) rest and satisfaction! Come back to your Lord, well pleased (yourself), and well pleasing unto Him! Enter you, then, among my devotees! And enter you My “To the righteous soul will be said: O (thou) soul, in (complete) rest and satisfaction! Heaven!” [Al-Qur’an 89:27] Come back to your Lord, well pleased (yourself), and well pleasing unto Him! Enter you, then, among my devotees! And enter you My Heaven!” [Al-Qur'an 89: 27-28] In Islam, an individual's life after death or Him in the heavens or in the earth,but it is in a clear their Hereafter, is very closely shaped by Record.That He may reward those who believe and do their present life. Life after death begins with good works.For them are pardon and a rich provision. the resurrection of man, after which there will But those who strive against our revelations, come a moment when every human will be shaken as challenging (Us), theirs will be a painful doom of they are confronted with their intentions and wrath.” [Al-Qur’an: 34: 3-5] deeds, good and bad, and even by their failure to do good in this life. On the Day of Judgment the entire record of people from the age of puberty The need to believe in life after death will be presented before God. God will weigh Belief in life after death has always been part of the ath Lifeafter De everyone’s good and bad deeds according to His teachings of the Prophets and is an essential condition Questions about Islam? Mercy and His Justice, forgiving many sins and of being a Muslim.Whenever we are asked to do or would you like to: multiplying many good deeds. -

Kant's Theoretical Conception Of

KANT’S THEORETICAL CONCEPTION OF GOD Yaron Noam Hoffer Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy, September 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________________ Allen W. Wood, Ph.D. (Chair) _________________________________________ Sandra L. Shapshay, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Timothy O'Connor, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Michel Chaouli, Ph.D 15 September, 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 Yaron Noam Hoffer iii To Mor, who let me make her ends mine and made my ends hers iv Acknowledgments God has never been an important part of my life, growing up in a secular environment. Ironically, only through Kant, the ‘all-destroyer’ of rational theology and champion of enlightenment, I developed an interest in God. I was drawn to Kant’s philosophy since the beginning of my undergraduate studies, thinking that he got something right in many topics, or at least introduced fruitful ways of dealing with them. Early in my Graduate studies I was struck by Kant’s moral argument justifying belief in God’s existence. While I can’t say I was convinced, it somehow resonated with my cautious but inextricable optimism. My appreciation for this argument led me to have a closer look at Kant’s discussion of rational theology and especially his pre-critical writings. From there it was a short step to rediscover early modern metaphysics in general and embark upon the current project. This journey could not have been completed without the intellectual, emotional, and material support I was very fortunate to receive from my teachers, colleagues, friends, and family. -

Bonaventure's Metaphysics of the Good

Theological Studies 60 (1999) BONAVENTURE'S METAPHYSICS OF THE GOOD ILIA DELIO, O.S.F. [Bonaventure offers new insight on the role of God the Father vis-à-vis the created world and the role of the Incarnate Word as metaphysical center of all reality. The kenosis of the Father through the self-diffusion of the good inverts the notion of patriarchy and underscores the humility of God in the world. By locating universals on the level of the singular and personal, Bonaventure transforms the Neoplatonic philosophical quest into a Christian metaphysics. The author then considers the ramifications of this for the contem porary world.] HE HIGH MIDDLE AGES were a time of change and transition, marked by T the religious discovery of the universe and a new awareness of the position of the human person in the universe. In the 12th century, a Dio- nysian awakening coupled with the rediscovery of Plato's Timaeus gave rise to a new view of the cosmos.1 Louis Dupré has described the Platonic revival of that century as the turn to a "new self-consciousness."2 In view of the new awakening of the 12th century, the question of metaphysical principles that supported created reality, traditionally the quest of the philosophers, began to be challenged by Christian writers. Of course it was not as if any one writer set out to overturn classical metaphysics; however, the significance of the Incarnation posed a major challenge. It may seem odd that a barely educated young man could upset an established philo sophical tradition, but Francis of Assisi succeeded in doing so. -

Pursuing Eudaimonia LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY STUDIES in ETHICS SERIES SERIES EDITOR: DR

Pursuing Eudaimonia LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY STUDIES IN ETHICS SERIES SERIES EDITOR: DR. DAVID TOREVELL SERIES DEPUTY EDITOR: DR. JACQUI MILLER VOLUME ONE: ENGAGING RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Editors: Joy Schmack, Matthew Thompson and David Torevell with Camilla Cole VOLUME TWO: RESERVOIRS OF HOPE: SUSTAINING SPIRITUALITY IN SCHOOL LEADERS Author: Alan Flintham VOLUME THREE: LITERATURE AND ETHICS: FROM THE GREEN KNIGHT TO THE DARK KNIGHT Editors: Steve Brie and William T. Rossiter VOLUME FOUR: POST-CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION Editor: Neil Ferguson VOLUME FIVE: FROM CRITIQUE TO ACTION: THE PRACTICAL ETHICS OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL WORLD Editors: David Weir and Nabil Sultan VOLUME SIX: A LIFE OF ETHICS AND PERFORMANCE Editors: John Matthews and David Torevell VOLUME SEVEN: PROFESSIONAL ETHICS: EDUCATION FOR A HUMANE SOCIETY Editors: Feng Su and Bart McGettrick VOLUME EIGHT: CATHOLIC EDUCATION: UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES, LOCALLY APPLIED Editor: Andrew B. Morris VOLUME NINE GENDERING CHRISTIAN ETHICS Editor: Jenny Daggers VOLUME TEN PURSUING EUDAIMONIA: RE-APPROPRIATING THE GREEK PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE CHRISTIAN APOPHATIC TRADITION Author: Brendan Cook Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition By Brendan Cook Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition, by Brendan Cook This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Brendan Cook All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

1A2ae.10.2.Responsio 2

THE TRINITARIAN GIFT UNFOLDED: SACRIFICE, RESURRECTION, COMMUNION JOHN MARK AINSLEY GRIFFITHS, BSC., MSC., MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2015 Abstract Contentious unresolved philosophical and anthropological questions beset contemporary gift theories. What is the gift? Does it expect, or even preclude, some counter-gift? Should the gift ever be anticipated, celebrated or remembered? Can giver, gift and recipient appear concurrently? Must the gift involve some tangible ‘thing’, or is the best gift objectless? Is actual gift-giving so tainted that the pure gift vaporises into nothing more than a remote ontology, causing unbridgeable separation between the gift-as-practised and the gift-as-it-ought-to- be? In short, is the gift even possible? Such issues pervade scholarly treatments across a wide intellectual landscape, often generating fertile inter-disciplinary crossovers whilst remaining philosophically aporetic. Arguing largely against philosophers Jacques Derrida and Jean-Luc Marion and partially against the empirical gift observations of anthropologist Marcel Mauss, I contend in this thesis that only a theological – specifically trinitarian – reading liberates the gift from the stubborn impasses which non-theological approaches impose. That much has been argued eloquently by theologians already, most eminently John Milbank, yet largely with a philosophical slant. I develop the field by demonstrating that the Scriptures, in dialogue with the wider Christian dogmatic tradition, enrich discussions of the gift, showing how creation, which emerges ex nihilo in Christ, finds its completion in him as creatures observe and receive his own perfect, communicable gift alignment. In the ‘gift-object’ of human flesh, believers rejoicingly discern Christ receiving-in-order-to-give and giving-in- order-to-receive, the very reciprocal giftedness that Adamic humanity spurned. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae MIRANDA, ASHLEY SDB Date of Birth: 1-05-1965 Current Address: Salesian Training Institute, Divyadaan Trust, Don Bosco Marg, Nasik – 422005. Phone: (0253) 2572402, 2573812 Email: [email protected] Religious Congregation Salesians of Don Bosco Province/Diocese Bombay Teaching experience 13 years Positions occupied: Teacher, Divyadaan: Salesian Institute of Philosophy, Nashik, 1987-89; 1994-96; 1999- 2002, 2006 onwards. Teacher and Principal, Divyadaan: Salesian Institute of Philosophy, Nashik, 2003- 2006. Rector, Divyadaan: Salesian Institute of Philosophy, Nashik, 2002-2008. Executive committee member of ACPI (Association of Christian Philosophers of India) from 2003-2006. Executive committee member of ARMS (Association of Rectors of Major Seminaries) from 2004-2007. Qualification : Bachelor of Philosophy, Divyadaan: Salesian Institute of Philosophy, Nashik, 1985. Master of Philosophy, Jnana Deepa Vidyapeeth, Pune, 1987. Bachelor of Theology, Kristu Jyoti College, Bangalore (affiliated to the Salesian Pontifical University, Rome), 1993. Ph.D. in Philosophy: Salesian Pontifical University, Rome, 1999. Thesis: "An Assessment of Alasdair MacIntyre's Theory of Virtue." Director: Giuseppe Abbà, SDB. Specialization: Virtue Ethics, Philosophical Anthropology, History of Philosophy Courses offered for the students of Bachelor of Philosophy: Philosophy of Morality (Ethics), Philosophy of Knowing Courses offered for students of Master of Philosophy Virtue Ethics, Philosophy of History, Educational Psychology, Seminars offered for the students of Masters of Philosophy Perspectives in Moral Education; Subaltern Perspectives on Human Dignity, Freedom and Justice; 1 Publications: books\articles\reviews\other "Intelligence and the Personal Life: Some Reflections from Emmanuel Mounier," Divyadaan: Journal of Philosophy, 4 (1988-89) 19-24. "Fides et Ratio and the Original Vocation of Philosophy," Divyadaan: Journal of Philosophy and Education, 10 (1999) 210-225. -

Original Monotheism: a Signal of Transcendence Challenging

Liberty University Original Monotheism: A Signal of Transcendence Challenging Naturalism and New Ageism A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries by Daniel R. Cote Lynchburg, Virginia April 5, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Cote All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet Dr. T. Michael Christ Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity Dr. Phil Gifford Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Daniel R. Cote Liberty University School of Divinity, 2020 Mentor: Dr. T. Michael Christ Where once in America, belief in Christian theism was shared by a large majority of the population, over the last 70 years belief in Christian theism has significantly eroded. From 1948 to 2018, the percent of Americans identifying as Catholic or Christians dropped from 91 percent to 67 percent, with virtually all the drop coming from protestant denominations.1 Naturalism and new ageism increasingly provide alternative means for understanding existential reality without the moral imperatives and the belief in the divine associated with Christian theism. The ironic aspect of the shifting of worldviews underway in western culture is that it continues with little regard for strong evidence for the truth of Christian theism emerging from historical, cultural, and scientific research. One reality long overlooked in this regard is the research of Wilhelm Schmidt and others, which indicates that the earliest religion of humanity is monotheism. Original monotheism is a strong indicator of the existence of a transcendent God who revealed Himself as portrayed in Genesis 1-11, thus affirming the truth of essential elements of Christian theism and the falsity of naturalism and new ageism. -

Transcending the Limits of Finitude in St. Bonaventure's Itinerarium Mentis

Transcending the Limits of Finitude In St. Bonaventure’s Itinerarium Mentis in Deum San Beda College Moses Aaron T. Angeles, Ph.D. he “Itinerarium Mentis in Deum” has been described as Finitude of Limits the Transcending an essentially Franciscan tract, guiding learned men in the spirit of St. Francis to his mode of contemplative life. Though intended by St. Bonaventure as a guide towards meditation and contemplation, it is our intention to emphasize and elaborate on a theme,T particularly on the question of transcendence and human finitude, within the Itinerarium rather than to controvert the prevailing scholarly judgments regarding the nature and utility of ... the work. St. Bonaventure’s description of how man comes to his self-realization or self-identity is simultaneously an inventory of man’s intellectual powers and operations with a collage of Scriptural injunctions regulating the course of intellectual introspection. The coalescence of these two dimensions is an entree to the Truth of God. After the reflection of the mind upon itself, man discovers that he is an imago Dei. The name imago was given by God to man in Genesis. But now, man re-enacts that part of Creation and appropriates the name to himself. The act of self-naming is a cry of attenuated triumph. The power to name is an activity of dominion, and the act of self-nomination is the consummate exhibition of human autonomy. First of all, the term “Transcendence” and “Person”1 is not very appropriate terms when it comes to St. Bonaventure and the Itinerarium. The term “Person” as we understood it now speaks about subjectivity, the self, uniqueness, autonomy, the Existential which is in stark contrast to the Boethian universal definition of person 1 St. -

March 2019 RADICAL ORTHODOXYT Theology, Philosophy, Politics R P OP Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics

Volume 5, no. 1 | March 2019 RADICAL ORTHODOXYT Theology, Philosophy, Politics R P OP Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics Editorial Board Oliva Blanchette Michael Symmons Roberts Conor Cunningham Phillip Blond Charles Taylor Andrew Davison Evandro Botto Rudi A. te Velde Alessandra Gerolin David B. Burrell, C.S.C. Graham Ward Michael Hanby David Fergusson Thomas Weinandy, OFM Cap. Samuel Kimbriel Lord Maurice Glasman Slavoj Žižek John Milbank Boris Gunjević Simon Oliver David Bentley Hart Editorial Team Adrian Pabst Stanley Hauerwas Editor: Catherine Pickstock Johannes Hoff Dritëro Demjaha Aaron Riches Austen Ivereigh Tracey Rowland Fergus Kerr, OP Managing Editor & Layout: Neil Turnbull Peter J. Leithart Eric Austin Lee Joost van Loon Advisory Board James Macmillan Reviews Editor: Talal Asad Mgsr. Javier Martínez Brendan Sammon William Bain Alison Milbank John Behr Michael S Northcott John R. Betz Nicholas Rengger Radical Orthodoxy: A Journal of Theology, Philosophy and Politics (ISSN: 2050-392X) is an internationally peer-reviewed journal dedicated to the exploration of academic and policy debates that interface between theology, philosophy and the social sciences. The editorial policy of the journal is radically non-partisan and the journal welcomes submissions from scholars and intellectuals with interesting and relevant things to say about both the nature and trajectory of the times in which we live. The journal intends to publish papers on all branches of philosophy, theology aesthetics (including literary, art and music criticism) as well as pieces on ethical, political, social, economic and cultural theory. The journal will be published four times a year; each volume comprising of standard, special, review and current affairs issues. -

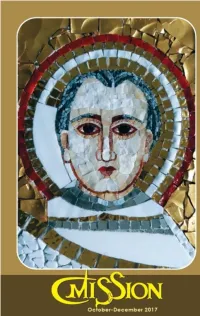

CMISSION News and Views on CMI Mission Around the Globe

CMISSION News and Views on CMI Mission around the Globe Volume 10, Number 4 October-December 2017 CMI General Department of Evangelization and Pastoral Ministry Prior General’s House Chavara Hills, Post Box 3105, Kakkanad Kochi 682 030, Kerala, India CMIssion News and Views on CMI Mission around the Globe (A Quarterly from the CMI General Department of Evangelization and Pastoral Ministry) Chief Editor: Fr. Saju Chackalackal CMI Editorial Board: Fr. Benny Thettayil CMI Fr. James Madathikandam CMI Fr. Saju Chackalackal CMI Advisory Board: Fr. Paul Achandy CMI (Prior General) Fr. Varghese Vithayathil CMI Fr. Sebastian Thekkedathu CMI Fr. Antony Elamthottam CMI Fr. Saju Chackalackal CMI Fr. Johny Edapulavan CMI Office: CMISSION CMI Prior General‟s House Chavara Hills, Post Box 3105, Kakkanad Kochi 682 030, Kerala, India Email: [email protected] Phone: +91 9400 651965 Printers: Viani Printings, Ernakulam North, Kochi 683 118 Cover: Saint Kuriakose Elias Chavara, a Portrait Done in Mosaic by Fr. Joby Koodakkattu CMI For private circulation only CONTENTS Editorial 7 Christian Missionary in Contemporary India: An Apostle of Life-Giving Touch Fr. Saju Chackalackal CMI Prior General’s Message 18 Venturing into the Unknown: Catholic Mission for the New Age Fr. Paul Achandy CMI Mar Paulinus Jeerakath CMI: Visionary of the 21 Church in Bastar Fr. Josey Thamarassery CMI There Is More Fun in the Philippines: Pastoral 40 Outreach of CMIs in Manila Fr. Joshy Vazhappilly CMI Golden Jubilee of Kaliyal Mission: CMI Mission in 55 Kanyakumari Fr. Benny Thottanani CMI The Monk Who Donated His Body: Swami 62 Sadanand CMI Fr. James M.