The Elusive Snowman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 DAY EVEREST BASE CAMP Ultimate Expeditions®

14 DAY EVEREST BASE CAMP 14 DAY EVEREST BASE CAMP Trip Duration: 14 days Trip Difficulty: Destination: Nepal Begins in: Kathmandu Activities: INCLUDED • Airport transfers • 2 nights hotel in Kathmandu before/after trek ® • Ground transportation Ultimate Expeditions • Flights to/from Kathmandu The Best Adventures on Earth. - Lukla • National Park fees Ultimate Expeditions® was born out of our need for movement, our • Expert guides & porters • Accommodations during connection with nature, and our passion for adventure. trek, double occupancy • Meals & beverages during We Know Travel. Our staff has traveled extensively to 40-50 countries trek each and have more than 10 years of experience organizing and leading adventures in all corners of the globe through the world's most unique, EXCLUDED remote, beautiful and exhilarating places. We want to share these • Airfare • Lunch or dinner at hotel destinations with you. • Beverages at hotel ® • Personal gear & equipment Why Ultimate Expeditions ? We provide high quality service without • Tips the inflated cost. Our goal is to work with you to create the ideal itinerary based on your needs, abilities and desires. We can help you plan every Ultimate Expeditions® aspect of your trip, providing everything you need for an enjoyable PH: (702) 570-4983 experience. FAX: (702) 570-4986 [email protected] www.UltimateExpeditions.com 14 DAY EVEREST BASE CAMP Itinerary DAY 1 Arrive Kathmandu Our friendly Ultimate Expeditions representative will meet you at the airport and drive you to your hotel in Kathmandu. During this meet and greet your guide will discuss the daily activities of your trip. DAY 2 Flight to Lukla - Trek to Phak Ding (8,713 ft / 2,656 m) Enjoy an exciting flight from Kathmandu to Lukla – this flight is roughly 45 minutes and offers great views of the Everest region if you can secure a seat on the left of the plane. -

Mt. Everest Base Camp Trek 15 Days

MT. EVEREST BASE CAMP TREK 15 DAYS TRIP HIGHLIGHTS Trekking Destination: Everest Base Camp, Nepal Maximum Altitude: 5,364m/17,594ft Duration of Trek: 15 Days Group Size: 1 People Or Above Mode of Trekking Tour: Tea House/Lodge Trekking Hour: Approx 5-7 Hours Best Season: March/April/May/Sept/Oct/Nov TRIP INTRODUCTION Everest Base Camp Trek is an opportunity to embark on an epic journey that Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay set off on in 1953. If you like adventure and you like to walk then it is once in a lifetime experience that takes you through the beautiful Khumbhu valley, spectacular Everest High Passes and stunning Sherpa village ultimately leading you to the foot of the Mighty Everest at 5430 meters. Trekking through the Everest also offers the opportunities to go sightseeing around Sagarmatha National Park (a world heritage site) and get a closer look at the sacred Buddhist monasteries. The stunning landscapes and the breathtaking views of the Himalayan giants including Everest, Lhotse, Cho Oyu and Ama Dablam are the highlights of the trek. Other major highlights include beautiful Rhododendron forest, glacial moraines, foothills, rare species of birds and animals, sunrise from Kala Patthar, the legendary Sherpas village their culture, tradition, festivals, and dances. We serve you with the best trekking adventure with our finest services. Our experienced guides will make your adventure enjoyable as well as memorable. Since your safety is our utmost concern we have tailored our itinerary accordingly. DETAIL PROGRAM ITINERARY Day 01: Arrival in Kathmandu City (1300m). After a thrilling flight experience through the Himalayas, observing magnificent views of snow-topped peaks, you land in this beautiful and culturally rich city of Kathmandu. -

Sherpa Expedition and Trekking Pvt.Ltd

SHERPA EXPEDITION AND TREKKING PVT.LTD. GPO BOX NO: 20969, Chaksibari Marg, Thamel, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: +977–1–4701288 [email protected], Website: www.sherpaexpeditiontrekking.com Gov. Authorized Regd No. 1011/2034 ________________________________________________________________________ Lobuche Peak Climbing 6,119 m/(20,075 ft) During the pre and post-monsoon seasons, Sherpa Expedition and Trekking will operate expeditions to one of Nepal’s most popular trekking peaks, Lobuche East (6,119m/20,075ft), located in Nepal's stunning Khumbu Valley. This is an ideal first step into Himalayan climbing, offering unparalleled views of the surrounding mountains and valleys, culminating in the sight of the towering peaks of Nuptse and Mount Everest. This is a very doable expedition for anyone in good shape and with a desire for high adventure. It is a journey with many visual highlights, including stunning views of the surrounding Himalayan peaks of Everest, Cho Oyu, Nuptse, Lhotse, Makalu, Ama Dablam and many, many more. Participants should be in good physical shape and have a background in basic mountaineering and/or a history of physical exercise. Instruction in mountaineering skills relative to the climb will be provided prior to the climbing commencing, as the ascent requires the use of crampons, ice ax, and fixed rope climbing. Day 01: Arrival in Kathmandu and transfer to hotel (1300m) Arrival at Kathmandu Tribhuvan International Airport, received by Sherpa Expedition and Trekking staff with a warm welcome and transfer to respective hotels with a briefing regarding Everest Base Camp trek, hotels, lodge on the route with do's and don’ts with evening group welcome dinner. -

Abominable Snowmen

86 Oryx ABOMINABLE SNOWMEN THE PRESENT POSITION By WILLIAM C. OSMAN HILL On ancient Indian maps the mountainous northern frontier is referred to as the Mahalangur-Himal, which may be trans- lated as the mountains of the big monkeys. In view of recent reports one naturally wonders whether the big monkeys referred to were the large langurs (Semnopithecus), which are known to ascend to the hills to altitudes of 12,000 feet, or to something still larger, which ranges to even higher altitudes. Ancient Tibetan books depict many representatives of the local fauna quite realistically, recognizably and in their correct natural settings. Among these, in addition to ordinary arboreal monkeys, is represented a large, erect, rock-dwelling creature of man-like shape, but covered with hair (Vlcek, 1959). One wonders whether this could relate to the cryptic being that has come to be known from the reports of Himalayan explorers and their Sherpa guides as the Abominable Snowman. Legends of large or smaller hairy man-like creatures which walk erect, possess savage dispositions and cause alarm to local humanity are rife in many parts of Asia (witness the stories of Nittaewo in Ceylon, Orang-pendek in Malaya, Almas in Mon- golia) and even in much more distant places (Sasquatch in British Columbia, Bigfoot in California and the Didi of the Guianan forests), to say nothing of similar legends from various parts of Africa. Among these the Yeti, or Abominable Snowman, is perhaps the most persistent. We are, however, at the present time, unaware of the real nature or origin of any one of these, though scores of supposedly correct solutions have been put forward in explanation by both zoologists and laymen. -

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 73. August 2020

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 73. August 2020 West face of Tengi Ragi Tau in Nepal's Rolwaling Himal.TENRAGIAU C CONTENTS THE PIOLETS D'OR 2020 AWARDS AT THE 25TH LADEK MOUNTAIN FESTIVAL Page 2 ~ 6 Dolpo – Far west Nepal Page 7 ~ 48 Introduction Inaba Kaori’s winter journey 2019-2020 Tamotsu Ohnishi’s 1999 & 2003 records. 1 Piolets d’Or 2020 An International Celebration of Grand Alpinism ©Lucyna Lewandowska Press Release # 3 - August 2020 THE PIOLETS D'OR 2020 AWARDS AT THE 25TH LADEK MOUNTAIN FESTIVAL Four remarkable ascents will be awarded Piolets d'Or in Ladek-Zdroj on September 19. The year 2019 turned out to be very rich for modern alpinism, with a substantial number of significant first ascents from all over the globe. The protagonists were alpinists of wide diversity. There were notable ascents by the "old guard" of highly-experienced high altitude climbers, but also fine achievements by a promising new generation of "young guns". Our eight-member international technical jury had the difficult task of making a choice, the intention being not to discard any remarkable climbs, but to choose a few significant ascents as "ambassadors" for modern, alpine style mountaineering. In the end the jury chose what we believe to be a consistent selection of four climbs. These will be awarded next month in Ladek. The four ascents comprise two from Nepal and two from Pakistan. Most had seen previous attempts and were on the radar of number of strong parties. All climbed to rarely visited, or in one case virgin, summits. -

Fate of Mountain Glaciers in the Anthropocene

Fate of Mountain Glaciers in the Anthropocene A Report by the Working Group Commissioned by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences 1921 2007 Courtesy of the Royal Geographical Society Courtesy of GlacierWorks Main Rongbuk Glacier (see inside page) May 11, 2011 The working group consists of glaciologists, climate scientists, meteorologists, hydrologists, physicists, chemists, mountaineers, and lawyers organized by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences at the Vatican, to contemplate the observed retreat of the mountain glaciers, its causes and consequences. This report resulted from a workshop in April 2011 at the Vatican. Cover Image: Main Rongbuk Glacier Location: Mount Everest, 8848 m, Tibet Autonomous Region Range: Mahalangur Himal, Eastern Himalayas Coordinates: 27°59’15”N, 86°55’29”E Elevation of Glacier: 5,060 - 6,462 m Average Vertical Glacier Loss: 101 m, 1921 - 2008 1985 2007 Morteratsch glacier (Alps). Courtesy of J. Alean, SwissEduc Declaration by the Working Group e call on all people and nations to recognise the serious and potentially irreversible impacts of global warming caused Wby the anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, and by changes in forests, wetlands, grasslands, and other land uses. We appeal to all nations to develop and implement, without delay, effective and fair policies to reduce the causes and impacts of climate change on communities and ecosystems, including mountain glaciers and their watersheds, aware that we all live in the same home. By acting now, in the spirit of common but differentiated responsibility, we accept our duty to one another and to the stewardship of a planet blessed with the gift of life. -

The New Height of Mount Everest

The new height of Mount Everest December 9, 2020 In news Recently, the Foreign Ministers of Nepal and China jointly certified the elevation of Mount Everest at 8,848.86 meters above sea level — 86 cm higher than what was recognized since 1954 Earlier measurement In 1954 the Survey of India determined its height using instruments like theodolites and chains, with GPS still decades away. The elevation of 8,848 m came to be accepted in all references worldwide — except by China In 1999, a US team put the elevation at 29,035 feet (nearly 8,850 m). This survey was sponsored by the National Geographic Society, US The recent measurement of the mountain After the devastating earthquake of April 2015, the government of Nepal(with technical assistance from New Zealand) declared that it would measure the mountain on its own, instead of continuing to follow the Survey of India findings of 1954. Sir Edmund Hillary, the first climber on the peak along with Nepal’s Tenzing Norgay in May 1953, worked as the mountain’s undeclared brand ambassador to the world In May 2019, the New Zealand government provided Nepal’s Survey Department (Napi Bibhag) with a Global Navigation Satellite, and trained technicians. China’s measurement It conducted the measurement separately The team of 120 (field workers and data analysts) was processing the data and computing results Both China & Nepal had signed a memorandum of understanding to jointly make public their results. The Chinese side conducted its measurements early this year. The methodology used for the measurement Both countries, China and Nepal announced the new height, and appreciated the mutual cooperation Nepal Joint secretary of Department of Survey said that they have used the previous methods applied in ascertaining the height as well as the latest data as well Global Navigational Satellite System (GNSS). -

Everest Base Camp Trek 12 Night / 13

Everest Base Camp Trek 12 night / 13 days Max. Altitude: [5545 m / 18187 ft] Group Size: Min 2 + 12 & Above Best period: Mid of September November and March to May. Day by day Itinerary: Day 01: Oct 25, 2020: - Arrival in Kathmandu [1350 m/4428 f], transfer to the Hotel Manaslu. Today, upon arrival from your respective countries, our representative will transfer you to the hotel from the airport. The rest of the day will be spent in the hotel itself. You can either relish the unique and delicious Nepali cuisine that Nepal is famous for or decide to stroll around the streets of your hotel. Breathe in the ambience of Kathmandu as much as you can. There will also be a full trek briefing on this evening. Overnight at Hotel in Kathmandu. Meals not included Day 02: Oct 26, 2020: - Fly from Kathmandu to Lukla [2840 m/9315 ft] trek to Phakding [2610 m / 8560 ft] 3-4 hours. Today after the breakfast we drive to domestic airport for Lukla flight. After 35-minute flight we enjoy one of the most beautiful air routes in the world culminating on a hillside surrounded by high mountainous peaks. We meet our other staffs then trek to Phakding. The trail leads gradual descent we will be at a Cheplung village from where we have a glimpse of Mt. Khumbila [5762 m/18900 ft], a sacred mountain which has never been climbed. From Cheplung, we then gradually descend until we reach Phakding which is distance 3-4 hours. Overnight at Lodge in Phakding. -

The Genusarthrorhaphis in the Himalayas, the Karakorum and the Subalpine and Alpine Regions of South-Eastern Tibet'

J. Hallori Bol. Lab. No. 80: 331-342 (Oct. 1996) THE GENUSARTHRORHAPHIS IN THE HIMALAYAS, THE KARAKORUM AND THE SUBALPINE AND ALPINE REGIONS OF SOUTH-EASTERN TIBET' WALTER OBERMAYER2 ABSTRACT. The yellow coloured taxa of the genus Arthrorhaphis (i.e. A. alpina var. alpina, A. alpina var. jungens, A. citrinella and A. vaci/lans) have been revised for the Himalaya Range, the Karakorum and for the south-east Tibetan fringe-mountains. Arthrorhaphis alpina var.jungens, usually growing on sandy soi!, appears to be a rather abundant lichen on open alpine (Kobresia- ) meadows, often associated with other weakly calciphilous crusts, such as Megaspora verrucosa, Phaeorrhiza nimbosa, Ph. sareptana, Psora decipiens and several Toninia species. Arthrorhaphis vacil/ans, with generally similar ecological requirements, and A. alpina var. alpina in more sheltered localities, are less frequent. Arthrorhaphis citrinel/a, growing on mosses or decaying plants rather than over pure soi!, is much more scarce in the study area than in the European Alps. INTRODUCTION Knowledge of the lichens of the Himalayas and adjacent areas rapidly increased when the series 'Flechten des Himalaya 1-17' was published between 1966 and 1977 (for a summary of the contributions see Poelt 1977: 447). About ten years later, another series 'Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Flechtenflora des Himalaya' ('Contribution to the knowledge of the lichen flora of the Himalayas'): began, in which mainly Prof. J. Poelt (Graz, Austria) and his co-workers presented their studies on different lichen genera or interesting species, i.e. Vezda & Poelt 1988 (gyalectoid and foliicolous lichens), Poelt & Obermayer 1991 (Bryonora), Obermayer 1992 (Lecanora somervellii), Poelt & Petutschnig 1992 (Xanthoria, Teloschistes) , Poelt & Grube 1992 (Protoparm elia), Poelt & Grube 1993a (Tephromela), Poelt & Grube 1993b (Lecanora, subg. -

Peak 6,420M, North-Northeast Ridge

AAC Publications Peak 6,420m, North-Northeast Ridge Nepal, Mahalangur Himal – Khumbu Section Jorge Martinez and I flew to Lukla and then, using no porters, carried all our gear to Pangboche over two days. From there we went up the Mingbo Valley (Nare Glacier on the HMG-Finn map), south of Ama Dablam, to a camp at 4,800m. Subsequently we moved to a base camp at 5,300m near a dry lake in extensive moraine. This was toward the southwest face of Ombigaichang, our original objective, which we found to be in a dangerous condition. We then walked four hours from camp to reach the glacier and reconnoiter Peak 6,420m, which lies in the southeast corner of the glacial cirque, on the ridge east of Melanphulan. On October 25 we left camp at 1 a.m. and crossed the glacier toward Peak 6,420m. There was fresh snow hiding crevasses, and the traverse was long and dangerous. We began climbing on the north face at about 5,700m, below enormous seracs, then headed up over windslab to the north-northeast ridge. It was cold and windy here, and although the difficulties were not great (snow, sometimes deep, to 70°), protection was sparse. We reached the short summit ridge and followed it pleasantly to the highest point, arriving at 11 a.m. We went back down the north-northeast ridge, with rappels from snow mushrooms, and continued toward Peak 5,985m so that we could rappel its rocky western flanks (three rappels). As we had no food left in base camp, we decided to continue down, taking a wrong turn and finally, at 9 p.m, arriving at the standard Ama Dablam base camp, where we spent the rest of the night. -

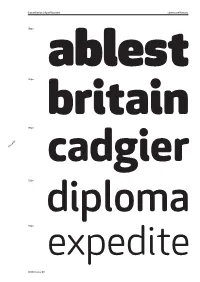

Constellation / Apex Rounded Lowercase Romans

Constellation / Apex Rounded Lowercase Romans 150pt ablest 140pt britain 135pt VILLAGE cadgier 125pt diploma 120pt expedite WWW.VLLG.COM Constellation / Apex Rounded Lowercase Italics 150pt zlotys 140pt yantai 135pt VILLAGE xenium 125pt whalery 120pt visitator WWW.VLLG.COM 2 Constellation / Apex Rounded Uppercase Romans 150pt FIORA 140pt GABLE 135pt VILLAGE HOKEY 125pt INURED 120pt JOURNO WWW.VLLG.COM 3 Constellation / Apex Rounded Uppercase Italics 150pt UNITS 140pt TWAIN 135pt VILLAGE SQUAD 125pt RADISH 120pt QUARTS WWW.VLLG.COM 4 Constellation / Apex Rounded All weights & styles Ultra & Ultra Italic 30pt APHORIZE BERGENIA carabiners dialogized ebriosity freehand Heavy & Heavy Italic 30pt GARDIERE HANDRAIL imitability jagdgÖttin knockout locations Bold & Bold Italic 30pt MOTORIZE NUMERICS VILLAGE objurgates polyvalent querencia recreated Medium & Medium Italic 30pt SEIGNORY TELONIUM unrequired variegated winterers xenotimes Book & Book Italic 30pt YEARLING ZABAIONE ancestorial breakdown chevelure delicately WWW.VLLG.COM 5 Constellation / Apex Rounded Sample text settings BOLD & BOLD ITALIC 10pt Sir George Everest himself opposed the name suggested by Waugh and told the Royal Geographical Socie ty in 1857 that Everest could not be written in Hindi nor pronounced by its native people. Waugh’s propos ed name prevailed despite the objections, and in 1865, the Royal Geographical Society officially adopted Mount Everest as the name for the highest mountain in the world. The modern pronunciation of Everest is different from Sir George’s pronunciation of his surname: eev-rist. In the early 1960s, the Nepalese go vernment coined the Nepali name Sagarmāthā or Sagar-Matha, meaning goddess of the sky. In 1802, th e British began the Great Trigonometric Survey of India to fix the locations, heights, and names of the wo rld's highest mountains. -

Tharke Kang, Northwest Ridge Nepal, Mahalangur Himal, Khumbu Section

AAC Publications Tharke Kang, Northwest Ridge Nepal, Mahalangur Himal, Khumbu Section Tharke Kang (6,710m) is a newly opened summit that sits on the northwest ridge of Hungchi (7,029m). This ridge rises from the Nup La (5,844m) and forms the frontier between Nepal and Tibet. A guided expedition led by Garrett Madison (USA) made the first known attempt on Tharke Kang in the autumn. The team trekked to a base camp at around 5,200m by the Gokyo Fifth Lake, above the west bank of the Ngojumba Glacier. They then completely avoided the icefall by helicoptering over it and onto the glacier plateau near the Nup La, where an advanced base was established at 5,820m on November 1. On this and the following day, members of the team climbed onto the crest of the northwest ridge and ascended about two-thirds of the way to the summit, fixing ropes on steeper sections. On summit day, November 3, the team left advanced base at 2 a.m., crossed the glacier for 45 minutes, and climbed about 150m up to the crest. They continued up the ridge, negotiating various degrees of steepness (sometimes vertical for sustained sections). The team was split into two groups, with Aang Purba, Lakpa Dandi Sherpa, and Madison out in front, fixing any difficulties, while the second group followed steadily behind. (Aang Phurba and Madison have worked together many times in recent years; Aang Phurba’s brother was working with Madison when he perished in the Khumbu Icefall avalanche in 2014.) The first group reached the summit at 9:15 a.m.