The Influence of Alchemy and Rosicrucianism in William

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII Th–XIX Th Centuries

REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña E-ISSN: 1659-4223 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Khalturin, Yuriy Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII th–XIX th centuries REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 7, núm. 1, mayo-noviembre, 2015, pp. 128-140 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369539930009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, Vol. 7, no. 2, Mayo - Noviembre 2015/ 128-140 128 Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysics in Russian Freemasonry of the XVIIIth – XIXth centuries Yuriy Khalturin PhD in Philosophy (Russian Academy of Science), independent scholar, member of ESSWE. E-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recibido: 20 de noviembre de 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 8 de enero de 2015 Palabras clave Cábala, masonería, rosacrucismo, teosofía, sofilogía, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanación, alquimia, la estrella llameante, columnas Jaquín y Boaz Keywords Kabbalah, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Sophiology, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanation, alchemy, Flaming Star, Columns Jahin and Boaz Resumen Este trabajo considera algunas conexiones entre la Cábala y la masonería en Rusia como se refleja en los archivos del Departamento de Manuscritos de la Biblioteca Estatal Rusa (DMS RSL). El vínculo entre ellos se basa en la comprensión tanto de la Cabala y la masonería como la filosofía simbólica y “verdaderamente metafísica”. -

Rosicrucianism from Its Origins to the Early 18Th Century

CHAPTER TWO ROSICRUCIANISM FROM ITS ORIGINS TO THE EARLY 18TH CENTURY In order to understand the 18th-century Rosicrucian revival it is necessary to know something of the origins and early history of Rosicrucianism. This ground has already been covered many times,1 but it is worth covering it again here in broad outline as a prelude to my main investigation. The Rosicrucian legend was born in the early 17th century in the uneasy period before religious tensions in Central Europe erupted into the Thirty Years' War. The Lutheran Reformation of a century earlier had finally shat tered the religious unity of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. On the other hand, as the historian Geoffrey Parker has observed, the Reformation had not produced the spiritual renewal that its advocates had hoped for.2 In the prevailing atmosphere of political and religious tension and spiritual malaise, many people turned, in their dismay, to the old millenarian dream of a new age. This way of thinking, dating back to the writings of the 12th-cen tury Calabrian abbot Joachim of Fiore, had surfaced at various times in the intervening centuries, giving rise to movements of the kind described by Nor man Cohn in his Pursuit of the Millennium3 and by Marjorie Reeves in her Joachim ofFiore and the Prophetic Future.4 Joachim and his followers saw history as unfolding in a series of three ages, corresponding to the three per sons of the Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in that order. They believed that hitherto they had been living in the Age of the Son, but that the Age of the Spirit was at hand. -

Rosicrucianism in the Contemporary Period in Denmark

Contemporary Rosicrucianism in Denmark 445 Chapter 55 Contemporary Rosicrucianism in Denmark Rosicrucianism in the Contemporary Period in Denmark Jacob Christiansen Senholt Rosicrucian ideas were present in Denmark already during the seventeenth century, fuelled by the publication of the tracts Fama fraternitatis rosae crucis and Confessio fraternitatis in Germany in 1614 and 1615 respectively. After a gap in the history of Rosicrucian presence in Denmark of almost 300 years, modern Rosicrucian societies spread across the world, and following this wave of Rosi cru cian fraternities, Danish offshoots of these fraternities also emerged. The modernday Rosicrucians and their presence in Denmark stem from two differ ent historical roots. The first is an influence from Germany via the Rosicrucian Society in Germany (RosenkreuzerGesellschaft in Deutschland), and the other comes from the United States, with the formation of Antiquus Mys ti cus que Ordo Rosæ Crucis (AMORC) by Harvey Spencer Lewis (1883–1939) in 1915. The Rosicrucian Fellowship The history of modern Rosicrucianism in Denmark starts in 1865 when Carl Louis von Grasshoff (1865–1919), later known under the pseudonym Max Heindel, was born. Although born in Denmark, Heindel was of German ances try, and spent most of his life travelling in both the United States and Germany. He was a member of the Theosophical Society and met with the later founder of Anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner, in 1907. In 1909 he published his major work, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception, which dealt with Christian mysticism and esotericism, and later that year Heindel founded The Rosicrucian Fellowship. It was a German spinoff of this group lead by occultist and theosophist Franz Hartmann (1838–1912) and later Hugo Vollrath, that later became influential in Denmark. -

Theosophical Siftings Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians Vol 6, No 15 Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians

Theosophical Siftings Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians Vol 6, No 15 Christian Rosenkreuz and the Rosicrucians by William Wynn Westcott Reprinted from "Theosophical Siftings" Volume 6 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England [Page 3] THE Rosicrucians of mediaeval Germany formed a group of mystic philosophers, assembling, studying and teaching in private the esoteric doctrines of religion, philosophy and occult science, which their founder, Christian Rosenkreuz, had learned from the Arabian sages, who were in their turn the inheritors of the culture of Alexandria. This great city of Egypt, a chief emporium of commerce and a centre of intellectual learning, flourished before the rise of the Imperial power of Rome, falling at length before the martial prowess of the Romans, who, having conquered, took great pains to destroy the arts and sciences of the Egypt they had overrun and subdued ; for they seem to have had a wholesome fear of those magical arts, which, as tradition had informed them, flourished in the Nile Valley; which same tradition is also familiar to English people through our acquaintance with the book of Genesis, whose reputed author was taught in Egypt all the science and arts he possessed, even as the Bible itself tells us, although the orthodox are apt to slur over this assertion of the Old Testament narrative. Our present world has taken almost no notice of the Rosicrucian philosophy, nor until the last twenty years of any mysticism, and when it does condescend to stoop from its utilitarian and money-making occupations, it is only to condemn all such studies, root and branch, as waste of time and loss of energy. -

INTRODUCTION Rosicrucianism Is a Theosophy Advanced by an Invisible

INTRODUCTION Rosicrucianism is a theosophy advanced by an invisible order of spir itual knights who in spreading Christian Hermeticism, Kabbalah, and Gnosis seek to enliven and to preserve the memory of Divine Wisdom, understood as a feminine flame of love called Sofia or Shekhinah, exoterically given as a fresh unfolded rose, yet, more akin to the blue fire of alchemy, the blue virgin. Rosicrucians have no organisation and there are no recognizable Rosicrucian individuals, but the order makes its presence known by leaving behind engram- matic writings in the genre of Hermetic-Platonic Christianity.1 The historical roots of Hermeticism is to be located in Ancient Egypt. Long before the rise of Christianity, Hermetic texts were struc tured around the belief that organisms contain sparks of a Divine mind unto which they each strive to attend. Things easily transform into others, thereby generating certain cyclical patterns, cycles that peri odically renew themselves on a cosmic scale. These transformations of life and death were enacted in the Hermetic Mysteries in Ancient Egypt through the gods Isis, Horus, and Osiris. In the Alexandrian period these myths were reshaped into Hermetic discourses on the transformations of the self with Thot, the scribal god. These dis courses were introduced in the west in 1474 when Marsilio Ficino translated the Hermetic Pimander from the Greek. The story of Chris tian Rosencreutz can be seen as a new version of these mysteries, specifically tempered by German Paracelsian philosophy on the lion of the darkest night, a biblical icon for how the higher self lies slum bering in consciousness.2 In this book, I develop the Rosicrucian theme from a Scandinavian perspective by linking selected historical events to scenarios of the emergence of European Rosicrucianism that have been advanced from other geographic angles. -

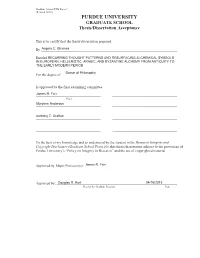

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry Introduction Freemasonry has a public image that sometimes includes notions that we practice some sort of occultism, alchemy, magic rituals, that sort of thing. As Masons we know that we do no such thing. Since 1717 we have been a modern, rational, scientifically minded craft, practicing moral and theological virtues. But there is a background of occult science in Freemasonry, and it is related to the secret fraternity of the Rosicrucians. The Renaissance Heritage1 During the Italian renaissance of the 15th century, scholars rediscovered and translated classical texts of Plato, Pythagoras, and the Hermetic writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, thought to be from ancient Egypt. Over the next two centuries there was a widespread growth in Europe of various magical and spiritual practices – magic, alchemy, astrology -- based on those texts. The mysticism and magic of Jewish Cabbala was also studied from texts brought from Spain and the Muslim world. All of these magical practices had a religious aspect, in the quest for knowledge of the divine order of the universe, and Man’s place in it. The Hermetic vision of Man was of a divine soul, akin to the angels, within a material, animal body. By the 16th century every royal court in Europe had its own astrologer and some patronized alchemical studies. In England, Queen Elizabeth had Dr. John Dee (1527- 1608) as one of her advisors and her court astrologer. Dee was also an alchemist, a student of the Hermetic writings, and a skilled mathematician. He was the most prominent practitioner of Cabbala and alchemy in 16th century England. -

Kabbalah, Magic & the Great Work of Self Transformation

KABBALAH, MAGIC AHD THE GREAT WORK Of SELf-TRAHSfORMATIOH A COMPL€T€ COURS€ LYAM THOMAS CHRISTOPHER Llewellyn Publications Woodbury, Minnesota Contents Acknowledgments Vl1 one Though Only a Few Will Rise 1 two The First Steps 15 three The Secret Lineage 35 four Neophyte 57 five That Darkly Splendid World 89 SIX The Mind Born of Matter 129 seven The Liquid Intelligence 175 eight Fuel for the Fire 227 ntne The Portal 267 ten The Work of the Adept 315 Appendix A: The Consecration ofthe Adeptus Wand 331 Appendix B: Suggested Forms ofExercise 345 Endnotes 353 Works Cited 359 Index 363 Acknowledgments The first challenge to appear before the new student of magic is the overwhehning amount of published material from which he must prepare a road map of self-initiation. Without guidance, this is usually impossible. Therefore, lowe my biggest thanks to Peter and Laura Yorke of Ra Horakhty Temple, who provided my first exposure to self-initiation techniques in the Golden Dawn. Their years of expe rience with the Golden Dawn material yielded a structure of carefully selected ex ercises, which their students still use today to bring about a gradual transformation. WIthout such well-prescribed use of the Golden Dawn's techniques, it would have been difficult to make progress in its grade system. The basic structure of the course in this book is built on a foundation of the Golden Dawn's elemental grade system as my teachers passed it on. In particular, it develops further their choice to use the color correspondences of the Four Worlds, a piece of the original Golden Dawn system that very few occultists have recognized as an ini tiatory tool. -

The Philosophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2014 The hiP losophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical Life Stanton Marlan Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Marlan, S. (2014). The hiP losophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical Life (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/874 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE: ALCHEMICAL IMAGINATION AND THE SOUL’S LOGICAL LIFE A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Stanton Marlan December 2014 Copyright by Stanton Marlan 2014 THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE: ALCHEMICAL IMAGINATION AND THE SOUL’S LOGICAL LIFE By Stanton Marlan Approved November 20, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Tom Rockmore, Ph.D. James Swindal, Ph.D. Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy Emeritus (Committee Member) (Committee Chair) ________________________________ Edward Casey, Ph.D. Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Stony Brook University (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D. Ronald Polansky, Ph.D. Dean, The McAnulty College and Chair, Department of Philosophy Graduate School of Liberal Arts Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE: ALCHEMICAL IMAGINATION AND THE SOUL’S LOGICAL LIFE By Stanton Marlan December 2014 Dissertation supervised by Tom Rockmore, Ph.D. -

ROSICRUCIANISM the Fraternity of the Rose Cross

ROSICRUCIANISM The Fraternity of the Rose Cross Council of Nine Muses February 10, 2007 Presented by William B. Brunk Sovereign Master Nine Muses Council No. 13 A cursory glance at the question of, “What is Rosicrucianism?” quickly leads one to be struck at how complex the subject really is. For, as much as Freemasonry has been known over the years as a secretive order, the Rosicrucian Order appears to be one much more secretive and mysterious. Dating from as early as the 15th century, it is a legendary and secretive order generally associated with the symbol of the Rose Cross, also found in certain rituals beyond “Craft” or “Blue Lodge” Masonry. The Rosicrucian movement first officially surfaced in 1614 in Cassel, Germany, with the publication of Fama Fraternitatis, des Loblichen Ordens des Rosenkreutzes (The Declaration of the Worthy Order of the Rosy Cross). The name “Rosicrucian” is thought to be derived from the symbol, a combination of a single rose upon a passion cross. Legend holds that the order was initiated with one Christian Rosenkreuz, born in 1378 in Germany. He was of good birth, but, being poor, was compelled to enter a monastery at a very early period of his life. At the age of one hundred years, he started with one of the monks on a pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulcher. He visited Damascus, Egypt, and Morocco, where he studied under the masters of the occult arts. Once he crossed over into Spain, however, his reception was not a terribly warm one and he determined to return to Germany to provide his own countrymen with the benefit of his studies and knowledge, and to establish a society for the cultivation of the sciences which he had studied during his travels. -

Melusine Machine

MELUSINE MACHINE The Metal Mermaids of Jung, Deleuze and Guattari [Received January 28th 2018; accepted July 28th 2018 – DOI: 10.21463/shima.12.2.07] Cecilia Inkol York University, Toronto <[email protected]> ABSTRACT: This article takes the image of the feminine water spirit or mermaid as the focus of its philosophical contemplation, using her image as a map to traverse the thought- realms of Jung, Deleuze and Guattari. The feminine, watery symbol in this elaboration acts as the glue that enjoins the ideas of Jung with Deleuze and Guattari and reveals the imbrication of their ideas. Through their streams of thought, the mermaid is formulated as an emblem of technology, as a metaphor that makes reference to the unconscious and its technological involutions, her humanoid-fish form providing an image of thought or way of talking about the transformation of form, and the flitting, swimming valences at work in the unconscious. KEYWORDS: Jung, Deleuze, Guattari, mermaid, nixie, unconscious, technology Introduction This article pivots around a particular image — the feminine water spirit, embodied in her forms of mermaid, nixie 1 or water sprite — through the thought-architectures of the philosophers Jung, Deleuze and Guattari; it traces the filaments that connect these philosophers to this feminine image, as well as to one another, unfurling the imbrication and lineage of their ideas. Within the thought-structures of Deleuze, Guattari and Jung, her fluid figure is elucidated as an emblem of technology, as a metaphor that refers to the unconscious and its technological involutions; her humanoid-fish form providing an image of thought or way of talking about the transformation of form, and the flitting, swimming valences at work in the unconscious. -

Rosicrucian Digest Vol 90 No 2 2012 Kabbalah

Kabbalah: A Brief Overview Joshua Maggid, Ph.D., FRC here are strong connections with traditional Jewish Kabbalah out of their Kabbalah in Rosicrucianism and religious context and presents them as TMartinism, and Kabbalah remains a collection of practical techniques for an important aspect of the teachings of finding happiness, fulfillment, prosperity, the Rosicrucian Order, AMORC and the relationships, etc. Traditional Martinist Order. In this article, Another common way of classifying Joshua Maggid, a longtime Rosicrucian and different types of Kabbalah is according to Martinist who has studied Kabbalah for many the kinds of activities involved. years, presents a brief overview of Kabbalah, including Jewish, Christian, and Hermetic “Theoretical Kabbalah” or “Theosophical Kabbalah. Kabbalah” includes a system of metaphysics, a description of the inner For those beginning to learn about it, workings of Divinity and how it interacts Kabbalah can be difficult and confusing. with the material world, and methods of Different books say different things. Any deriving esoteric interpretations of the two books on Kabbalah may address Holy Scriptures.3 completely different topics, or they “Meditative Kabbalah” consists of a may provide conflicting definitions and wide variety of practices aimed at attaining interpretations of the same material. In higher states of consciousness, exploring the addition, authors use different English spiritual realm, encountering the Divine, spellings for the same Hebrew terms. and receiving new spiritual insights.4 This One reason for this is that there are is also referred to as “Mystical Kabbalah” several different systems or traditions and “Prophetic Kabbalah.” that all refer to themselves as “Kabbalah.” “Practical Kabbalah” refers to theurgy There is Jewish Kabbalah, Christian and magic, attempting to influence the 1 Kabbalah, and Hermetic Kabbalah.