View Full Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congo's Enough Moment

Congo’s Enough Moment The Case for Conflict Minerals Certification and Army Reform John Prendergast October 20101 At rare moments during the course of a war, a confluence of factors come together to provide a window of opportunity for real conflict transformation. Now Congo has a unique opportunity to bring an end to more than 125 years of having its people and resources pillaged by colonial powers, international traders, neighbors, and foreign and domestic armed groups. Growing international attention to atrocities in Congo, both recent and historical, and widespread interest in conflict minerals has shined a spotlight on eastern Congo as it has never done before—from the U.S. Congress, from regional heads of state, and from multinational companies. This has opened a significant new window for policy reform and it is time for the U.S. government and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to help leverage the end of the war in eastern Congo through leadership on two of the issues that will catalyze a broader solution to the cycles of violence there: minerals certification and comprehensive army reform. Consumers and human rights activists in America and around the world are saying “Enough is Enough” of the killing, raping, and smuggling that has helped to satisfy our demand for cheaper cell phones, laptops, and other products powered in part by conflict minerals from the Congo. The result is congressional legislation—signed by President Obama—that requires real transparency from those companies profiting from this exploitation.2 That message has echoed from the board rooms of multinational compa- nies to the presidential palaces of Central African leaders, right down to the rank and file of the rebel groups and army units that feed off of the war. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Breaking Open the Sexual Harassment Scandal

Nxxx,2017-10-06,A,018,Cs-4C,E1 , OCTOBER 6, 2017 FRIDAY NATIONAL K THE NEW YORK TIMES 2017 IMPACT AWARD C M Y N A18 Claims of Sexual Harassment Trail a Hollywood Mogul From Page A1 clined to comment on any of the settle- ments, including providing information about who paid them. But Mr. Weinstein said that in addressing employee con- cerns about workplace issues, “my motto is to keep the peace.” Ms. Bloom, who has been advising Mr. Weinstein over the last year on gender and power dynamics, called him “an old dinosaur learning new ways.” She said she had “explained to him that due to the power difference between a major studio head like him and most others in the in- dustry, whatever his motives, some of his words and behaviors can be perceived as Breaking Open the Sexual inappropriate, even intimidating.” Though Ms. O’Connor had been writ- ing only about a two-year period, her BY memo echoed other women’s com- plaints. Mr. Weinstein required her to have casting discussions with aspiring CHRISTOPHER actresses after they had private appoint- ments in his hotel room, she said, her de- scription matching those of other former PALMERI employees. She suspected that she and other female Weinstein employees, she wrote, were being used to facilitate li- Late Edition Harassment Scandal aisons with “vulnerable women who Today, clouds and sunshine, warm, hope he will get them work.” high 78. Tonight, mostly cloudy, The allegations piled up even as Mr. mild, low 66. Tomorrow, times of Weinstein helped define popular culture. -

SHIRLEY MACLAINE to RECEIVE 40Th AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

SHIRLEY MACLAINE TO RECEIVE 40th AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD America’s Highest Honor for a Career in Film to be Presented June 7, 2012 LOS ANGELES, CA, October 9, 2011 – Sir Howard Stringer, Chair of the American Film Institute’s Board of Trustees, announced today the Board’s decision to honor Shirley MacLaine with the 40th AFI Life Achievement Award, the highest honor for a career in film. The award will be presented to MacLaine at a gala tribute on Thursday, June 7, 2012 in Los Angeles, CA. TV Land will broadcast the 40th AFI Life Achievement Award tribute on TV Land later in June 2012. The event will celebrate MacLaine’s extraordinary life and all her endeavors – movies, television, Broadway, author and beyond. "Shirley MacLaine is a powerhouse of personality that has illuminated screens large and small across six decades," said Stringer. "From ingénue to screen legend, Shirley has entertained a global audience through song, dance, laughter and tears, and her career as writer, director and producer is even further evidence of her passion for the art form and her seemingly boundless talents. There is only one Shirley MacLaine, and it is AFI’s honor to present her with its 40th Life Achievement Award." Last year’s AFI Tribute brought together icons of the film community to honor Morgan Freeman. Sidney Poitier opened the tribute, and Clint Eastwood presented the award at evening’s end. Also participating were Casey Affleck, Dan Aykroyd, Matthew Broderick, Don Cheadle, Bill Cosby, David Fincher, Cuba Gooding, Jr., Samuel L. Jackson, Ashley Judd, Matthew McConaughey, Helen Mirren, Rita Moreno, Tim Robbins, Chris Rock, Hilary Swank, Forest Whitaker, Betty White, Renée Zellweger and surprise musical guest Garth Brooks. -

Gender Inequality in the Movie Industry

Running head: GENDER INEQUALITY IN THE MOVIE INDUSTRY Gender Inequality in the Movie Industry: A Big Data Analysis of Female Underrepresentation Sebastián Cole Poma-Murialdo Student ID: 11351446 Master Thesis Graduate School of Communication Research Master in Communication Science University of Amsterdam Supervisor: dr. Jeroen Lemmens February 1st, 2019 GENDER INEQUALITY IN THE MOVIE INDUSTRY 1 Abstract The current study aimed to evaluate gender inequality in the movie industry. The gender of the cast and top crew positions from all 4885 feature films that received a wide release in United States between 1982 and 2017 were evaluated. Data was collected by scraping online movie databases. In the first part of the study, three types of representation were considered. First, the analysis of the numerical representation confirmed that there is high gender inequality in both cast and crew. Second, the examination of the quality of these representations revealed that, while all genres are male dominated, comedy, drama, romance and music have a higher proportion of women that the other genres (female genres). An analysis using the Bechdel test, used as a measure of female independence, showed that most movies from female genres pass the test, while movies from other genres fail it. Third, the analysis of the centrality of the representations showed no significant difference between big and small studio size, as both were male dominated. The relationship between cast and crew indicated that a higher proportion of women in the crew increases the proportion of women in the cast, especially for female genres. Finally, the second part of the study evaluated the relationship between the cast and crew’s gender and movie success. -

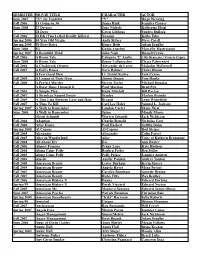

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

26, Regal Green Hills Stadium 16 and Downtown Nashville

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 2014 Deb Pinger [email protected] 615-742-2500 or 615-598-6440 2014 NASHVILLE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES Narrative and New Directors Competition Titles April 17 – 26, Regal Green Hills Stadium 16 and Downtown Nashville World Premieres The Identical, featuring: Ashley Judd, Ray Liotta, Seth Green, Blake Rayne, Joe Pantoliano Undiscovered Gyrl, featuring: Britt Robertson, Kimberly Williams-Paisley, Martin Sheen, Christian Slater, Robert Patrick, Justin Long Grace, featuring: Sharon Lawrence, Annika Marks Nashville, TN - The Nashville Film Festival (NaFF) today announced the film line-up for the Narrative and New Director Competitions, taking place April 17 – 26, at Regal Green Hills Stadium 16. NaFF has expanded to 10 days and two locations, with competition films, red carpet events, and opening and closing night parties at Regal Green Hills Stadium 16 and free films nightly at the Nissan Multicultural Village at Walk of Fame Park, downtown Nashville “I’m excited that we have so many outstanding and diverse films this year,” said Artistic Director, Brian Owens. “We are presenting a broad range of films – not only in voice, but in style. We have traditional narratives that are extremely well done, and experiments in form. Comedy played a stronger role this year than it has in the past, added Owens. “Every year the quality of films at NaFF is stellar,” said Ted Crockett, Executive Director. “The competition gets steeper with so many entries from all over the world. Also, as the profile of Nashville continues to rise, so do we.” The Nashville Film Festival is open to the public. -

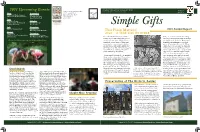

2021 Upcoming Events This Place Matters!

SHAKER VILLAGE OF PLEASANT HILL 2021 Upcoming Events Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill Volume I Nonprofit Org DEVELOPMENT NEWSLETTER Number 3 May September 3501 Lexington Road U.S. Postage Riverboat Rides Launch Harvest Fest Harrodsburg, KY 40330 PAID Music on the Lawn Debuts Community Sing shakervillageky.org Permit #1 Hard Cider Bash 859.734.5411 Lexington, KY June Summer Camp October Father’s Day Weekend & Trick-or-Treat Vintage Baseball Boo Cruise Simple Gifts July November Mercer County Week Quail Dinner 2020 Annual Report Blessing of the Hounds This Place Matters! August Craft Fair December 2020 - A YEAR LIKE NO OTHER SVPH 60 Year Incorporation Illuminated Evenings Anniversary Tea Time with Mrs. Claus The staff and administration at Shaker Early on, our team committed to telling Village entered 2020 with a high level of the story of the Kentucky Shakers through Please check dates and times at shakervillageky.org energy and excitement. 2019 had been a our digital media platforms. Bringing our remarkable year at Shaker Village, and humanities programming to you when we put in place a great number of plans you could not physically visit the Village, for 2020 that would further enhance the enabled us to act as a source of education, guest experience. But, “life is what happen entertainment and an uplifting presence. to us while we are making other plans” As we reached out to you – our guests and (Allen Saunders; John Lennon). supporters – to share this digital content, we received an outpouring of care and “As a non-profit cultural site, the mandated concern that meant so much to the staff closure in the early weeks of the pandemic who care for this powerful place every day. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

JOHN E. JACKSON Make-Up Artist IATSE 706

JOHN E. JACKSON Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 FILM COMET Department Head Milestone Media Director: Sam Esmail Cast: Emmy Rossum, Justin Long KNIGHT OF CUPS Department Head Waypoint Entertainment Director: Terrence Malick Cast: Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman VOYAGE OF TIME Department Head Sovereign Films, Plan B Entertainment Director: Terrence Malick Cast: Brad Pitt, Emma Thompson THE TOWN Department Head GK Films, Warner Bros. Pictures Personal Make-Up Artist to Ben Affleck Director: Ben Affleck Cast: Ben Affleck, Rebecca Hall EXTRACT Personal Make-Up Artist to Ben Affleck 3 Arts Entertainment, Miramax Films Director: Mike Judge STATE OF PLAY Personal Make-Up Artist to Ben Affleck Universal Pictures Director: Kevin MacDonald THE INFORMERS Department Head Senator International Director: Gregor Jordan Cast: Billy Bob Thornton, Winona Ryder, Jon Foster HE’S JUST NOT THAT INTO YOU Personal Make-Up Artist to Ben Affleck New Line Cinemas, Flower Films Director: Ken Kwapis CROSSING OVER Department Head C.O. Films Director: Wayne Kramer Cast: Harrison Ford, Ashley Judd, Ray Liotta, Alice Braga, Sean Penn LOVE IN THE TIME OF CHOLERA Department Head New Line Cinema Director: Mike Newell Cast: Javier Bardem, Giovanna Mezzogiorno, Benjamin Bratt, Catalina Sandino Moreno GONE, BABY, GONE Department Head Miramax Films Director: Ben Affleck Cast: Ed Harris, Michelle Monaghan, Casey Affleck THE MILTON AGENCY John E. Jackson 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Make-Up Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 5 BEOWULF Department Head Paramount Pictures Director: Robert Zemeckis Cast: Brendan Gleeson, Antony Hopkins, Ray Winstone, Robin Wright-Penn, Angelina Jolie, John Malkovich, Crispin Glover, Alison Lohman HOLLYWOODLAND Personal Make-Up Artist to Ben Affleck TJ Productions, Inc. -

Movie Suggestions for 55 and Older: #4 (141) After the Ball

Movie Suggestions for 55 and older: #4 (141) After The Ball - Comedy - Female fashion designer who has strikes against her because father sells knockoffs, gives up and tries to work her way up in the family business with legitimate designes of her own. Lots of obstacles from stepmother’s daughters. {The} Alamo - Western - John Wayne, Richard Widmark, Laurence Harvey, Richard Boone, Frankie Avalon, Patrick Wayne, Linda Cristal, Joan O’Brien, Chill Wills, Ken Curtis, Carlos Arru , Jester Hairston, Joseph Calleia. 185 men stood against 7,000 at the Alamo. It was filmed close to the site of the actual battle. Alive - Adventure - Ethan Hawke, Vincent Spano, James Newton Howard, et al. Based on a true story. Rugby players live through a plane crash in the Andes Mountains. When they realize the rescue isn’t coming, they figure ways to stay alive. Overcoming huge odds against their survival, this is about courage in the face of desolation, other disasters, and the limits of human courage and endurance. Rated “R”. {The} American Friend - Suspense - Dennis Hopper, Bruno Ganz, Lisa Kreuzer, Gerard Blain, Nicholas Ray, Samuel Fuller, Peter Lilienthal, Daniel Schmid, Jean Eustache, Sandy Whitelaw, Lou Castel. An American sociopath art dealer (forged paintings) sells in Germany. He meets an idealistic art restorer who is dying. The two work together so the German man’s family can get funds. This is considered a worldwide cult film. Amongst White Clouds - 294.3 AMO - Buddhist, Hermit Masters of China’s Zhongnan Mountains. Winner of many awards. “An unforgettable journey into the hidden tradition of China’s Buddhist hermit monks.