Kanhaiya Kumar in Begusarai: Old Fault Lines and New Struggles for Radical Political Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

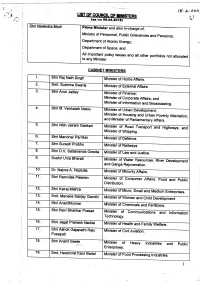

Shri Narendra Modi Prime Minister and Also In-Charge Of

LIST OF COUNCIL OF MINISTERS WITH UPDATED PORTFOLIOS (as on 14.08.2020) Shri Narendra Modi Prime Minister and also in-charge of: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Department of Atomic Energy; Department of Space; and All important policy issues; and All other portfolios not allocated to any Minister. CABINET MINISTERS 1. Shri Raj Nath Singh Minister of Defence 2. Shri Amit Shah Minister of Home Affairs 3. Shri Nitin Jairam Gadkari Minister of Road Transport and Highways; and Minister of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises 4. Shri D.V. Sadananda Gowda Minister of Chemicals and Fertilizers 5. Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman Minister of Finance; and Minister of Corporate Affairs 6. Shri Ramvilas Paswan Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution 7. Shri Narendra Singh Tomar Minister of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare; Minister of Rural Development; and Minister of Panchayati Raj 8. Shri Ravi Shankar Prasad Minister of Law and Justice; Minister of Communications; and Minister of Electronics and Information Technology 9. Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal Minister of Food Processing Industries 10. Shri Thaawar Chand Gehlot Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment 11. Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar Minister of External Affairs 12. Shri Ramesh Pokhriyal ‘Nishank’ Minister of Education 13. Shri Arjun Munda Minister of Tribal Affairs 14. Smt. Smriti Zubin Irani Minister of Women and Child Development; and Minister of Textiles 15. Dr. Harsh Vardhan Minister of Health and Family Welfare; Minister of Science and Technology; and Minister of Earth Sciences Page 1 of 4 16. Shri Prakash Javadekar Minister of Environment, Forest and Climate Change; Minister of Information and Broadcasting; and Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises 17. -

Star Campaigners of Lndian National Congress for West Benqal

, ph .230184s2 $ t./r. --g-tv ' "''23019080 INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 24, AKBAR ROAD, NEW DELHI'110011 K.C VENUGOPAL, MP General Secretary PG-gC/ }:B U 12th March,2021 The Secretary Election Commission of lndia Nirvachan Sadan New Delhi *e Sub: Star Campaigners of lndian National Congress for West Benqal. 2 Sir, The following leaders of lndian National Congress, who would be campaigning as per Section 77(1) of Representation of People Act 1951, for the ensuing First Phase '7* of elections to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengat to be held on 2ffif M-arch br,*r% 2021. \,/ Sl.No. Campaiqners Sl.No. Campaiqners \ 1 Smt. Sonia Gandhi 16 Shri R"P.N. Sinqh 2 Dr. Manmohan Sinqh 17 Shri Naviot Sinqh Sidhu 3 Shri Rahul Gandhi 18 ShriAbdul Mannan 4 Smt. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra 19 Shri Pradip Bhattacharva w 5 Shri Mallikarjun Kharqe 20 Smt. Deepa Dasmunsi 6 ShriAshok Gehlot 21 Shri A.H. Khan Choudhary ,n.T 7 Capt. Amarinder Sinqh 22 ShriAbhiiit Mukheriee 8 Shri Bhupesh Bhaohel 23 Shri Deependra Hooda * I Shri Kamal Nath 24 Shri Akhilesh Prasad Sinqh 10 Shri Adhir Ranian Chowdhury 25 Shri Rameshwar Oraon 11 Shri B.K. Hari Prasad 26 Shri Alamqir Alam 12 Shri Salman Khurshid 27 Mohd Azharuddin '13 Shri Sachin Pilot 28 Shri Jaiveer Sherqill 14 Shri Randeep Singh Suriewala 29 Shri Pawan Khera 15 Shri Jitin Prasada 30 Shri B.P. Sinqh This is for your kind perusal and necessary action. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, IIt' I \..- l- ;i.( ..-1 )7 ,. " : si fqdq I-,. elS€ (K.C4fENUGOPAL) I t", j =\ - ,i 3o Os 'Ji:.:l{i:,iii-iliii..d'a !:.i1.ii'ji':,1 s}T ji}'iE;i:"]" tiiaA;i:i:ii-q;T') ilem€s"m} il*Eaacr:lltt,*e Ge rt r; l-;a. -

MSME Insider September 2019

YEAR ANNIVERSARY 1EDITION MSME INSIDER •SEP 2019•VOL XIII• MSME INSIDER MSME INSIDER COMPLETES1 FROM THE DESK OF JS(SME) SMT. ALKA ARORA It gives me pleasure to be a part of the 1st anniversary edition of the MSME Insider. The idea of the e-newsletter took shape through a humble beginning made by the Ministry in September 2018 and continues till date. In this short but eventful journey, we have been enriched with a variety of experience associated with the preparation of the e-newsletter. The e-newsletter has been instrumental in increasing awareness, providing basic information about our schemes and programs and the readers were benefited in the best possible way. This e-newsletter features interesting articles written in an engaging manner, government decisions about the sector, latest innovations, training programs, etc. It has been successful in highlighting the strategic importance of the MSME sector in the present economic scenario, bringing out the imminent challenges for the MSMEs in India and the way forward to help MSME sector achieve its full potential. The dream of our Hon’ble Prime Minister for a self-reliant India inspires us to do more work in the field of entrepreneurship. Read more here AROUND THE MINISTRY 2 DIGITAL CORNER ESTABLISHMENT OF 15 NEW TCs UNDER TCSP Fifteen new Technology Centres Bhiwadi, Baddi, Bengaluru, Durg, (TC) are being set up under Puducherry, Vishakhapatnam, Technology Centre Systems Sitarganj, Bhopal, Kanpur, Imphal , To bring the MSME sector and design Programme (TCSP) at an estimated Ernakulam and Greater Noida are expertise on a common platform and cost of Rs. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

The Radical Humanist on Website

Articles and Features: Present Social Scenario In our country there is continuous fall in the economic or standard of all democratic institutions. administrative, one Particularly the increasing criminalization among finds that it is political life of India where known criminals are enveloped in gloom, elected and become members of apex political frustration (Late Ramesh Korde institutions called parliament and also of V.M.Tarkunde). provincial legislative assemblies that administer At present as reported, nearly more than all the aspects of country. This has resulted into about thirty percent population live below enormous rise in administrative corruption. poverty line with million unemployed or semi- Present scenario presents criminals and employed and at the same time rapid growth of anti-social elements have been gaining population aggravating both poverty and acceptability in social and political area. It is unemployment. The result is, Indian democracy reported that in several parts of our country is and invariably continue to be weak, shaky where mafia leaders have become political and unstable. bosses. This has led to enormous increase of The present prevailing economic, social, administrative corruption by leaps and bounds. cultural inequalities, democracy is confined to It has become all pervasive and threatens to political sphere in not likely to continue in India become way of life so that it does not evoke for long time and will not lead to deeper and any moral revulsion. moral meaningful democracy. Even though civil liberties are guaranteed by In India political parties are involved in our constitution, however in present prevailing unprincipled struggle for power that has political and economic situation where only divorced moral principle from political practice. -

Page7.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU WEDNESDAY, APRIL 23, 2014 (PAGE 7) Coalgate probe: CBI summons Modi will be best PM in Cong releases video clips former Coal Secretary NEW DELHI, Apr 22: India's history: Raman Singh of alleged hate speeches NEW DELHI, Apr 22: very core of the country," munal division and are openly CBI today summoned former Coal Secretary P C Parakh for NEW DELHI, Apr 22: the Lok Sabha polls. Surjewala said, adding that the trading in the politics of poison questioning on April 25 in connection with a case for alleged abuse "Modi will be the best Prime Stepping up its campaign Rejecting criticism that BJP's Prime Ministerial candi- as a weapon of last resort to gar- of official position in granting a coal block in Odisha to Hindalco, Minister in the history of India. against Narendra Modi, there was infighting within BJP, date was on the same dais with ner votes," he said in a written a company of Aditya Birla Group. Under his leadership, India will Congress today released video Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Kadam and was seen "relishing" statement. 69-year-old Parakh, who has been critical of CBI's action espe- not only realize its true potential clips of alleged "hate speeches" Raman Singh says that there the Shiv Sena leader's speech Surjewala said that this poli- cially its Director Ranjit Sinha for registering a case against him, but also get back the pride of of several BJP, Sangh Parivar was no friction among the lead- and "applauding" him by clap- tics of spreading "divisive com- has now been asked to appear before the agency on Friday during place amongst comity of and Shiv Sena leaders and ers and asserted that Narendra ping. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Indian student protests and the nationalist–neoliberal nexus Journal Item How to cite: Gupta, Suman (2019). Indian student protests and the nationalist–neoliberal nexus. Postcolonial Studies, 22(1) pp. 1–15. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Institute of Postcolonial Studies Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1080/13688790.2019.1568163 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Postcolonial Studies Vol. 22 Issue 1, 2019, Print ISSN: 1368-8790 Online ISSN: 1466- 1888 Accepted, pre-copy edited version Indian Student Protests and the Nationalist-Neoliberal Nexus Suman Gupta Professor of Literature and Cultural History / Head of the Department of English and Creative Writing, The Open University UK [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses the wider relevance of recent, 2014 and onwards, student protests in Indian higher education institutions, with the global neoliberal reorganisation of the sector in mind. The argument is tracked from specific high-profile junctures of student protests toward their grounding in the national/state level situation and then their ultimate bearing on the prevailing global condition. In particular, this paper considers present-day management practices and their relationship with projects to embed conservative and authoritarian norms in the higher education sector. -

Government of India Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 4279 TO BE ANSWERED ON 07.01.2019 DEVELOPMENT OF MSME CLUSTERS 4279. SHRI RAJIV PRATAP RUDY: SHRI NALIN KUMAR KATEEL: SHRI D. K. SURESH: Will the Minister of MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government is taking any measure to introduce cluster development mechanism to align the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) growth with the job creation agenda, if so, the details thereof along with the number of clusters developed under the MSME cluster development programme during each of the last four years; (b) the turnover, production and the number of jobs created therefrom within each of these clusters during the said period; (c) whether the clusters under this programme export their products and if so, the details thereof; and (d) whether the Government has any schemes for unorganised clusters of MSMEs and if so, the details thereof and if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDANT CHARGE) FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (SHRI GIRIRAJ SINGH) (a): The Micro and Small Enterprises Cluster Development Programme (MSE-CDP) is implemented by Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises and 22 clusters have been completed during financial year 2014-15 to 2017-18. (b)&(c): As per the information collected from respective clusters by MSME- Development Institutes, the details of turnover, production, jobs creation and exports of each of these clusters are enclosed (Annexure). (d): The MSMEs, not covered under MSE-CDP scheme can avail of benefits under other schemes of the Ministry such as Scheme of Fund for Regeneration of Traditional Industries (SFURTI), National Manufacturing Competitiveness Programme (NMCP), Zero Defect and Zero Effect (ZED), A Scheme for promoting Innovation, Rural Industry & Entrepreneurship (ASPIRE), Marketing Promotion Schemes etc. -

REV MINISTER BOOK.Cdr

December 2020 REWIND Hon’ble Union Minister Shri Mansukh Mandaviya QUOTE OF THE MINISTER Sagarmala could Create One Crore Jobs In The Next Decade DEVELOPMENT DISCOURSE Meeting with Ambassador to Argentina, Paraguay and Uraguay Shri Dinesh Bhatia Ji Meeting with Hon’ble Governor of West Bengal, Shri Jagdeep Dhankar Ji at Raj Bhawan in Kolkata The Sagarmala Seaplane Services Project Meeting with Union Minister of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry & Dairying Shri Giriraj Singh Ji Meeting with Hon’ble Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh Jairam Thakur Ji HAR KAAM DESH KE NAAM DBT Projects Review Team IWAI embarks on survey of Saryu river, Ayodhya 'Chai Pe Charcha' with the senior ofcials of Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways Visit to Inland Waterways Authority of India, Farakka The Multi Modal Logistics Park at Haldia in West Bengal MV RN Tagore started its journey to test the planned scheduled service between Varanasi and Kolkata Annual seminar on 'Fertilizer and Agriculture during COVID-19’ Hazira Ghogha Ro-Pax Ferry Service receives great response Webinar session on 'Plastic Recycling and Waste Management in India’ Cabinet approval on 'Development of Western Dock Project including Deepening and Optimisation of Inner Envisioning to achieve PM Shri Narendra Modi Ji’s Green Energy Mission Harbour facilities to handle Cape size vessels at Paradip Port Department of Fertilizers won 'Digital India Award 2020’ IN THE SERVICE OF PEOPLE Shri Mansukh Mandaviya interacted with intellectuals on Government of India’s vision Meeting with members from -

Press Release-18.02.2019

W “TCFL 16 iii—«men m W 7-125 flown-110066, s'fic'fln GAIL BHAWAN, 16 BHIKAIJI CAMA PLACE NEW DELHI—110066 INDIA W ($23") 1:r>>|==r/PHONE;+9111126182955 (we W in em Wm We?) W/FAXHQl 11 26185941 GAIL (India) Limited) ELEM/Email: [email protected] (A Government of India Undertaking — A Maharatna Company) ND/GAIL/SECTT/2019 18th February, 2019 1. Listing Department 2. Listing Department National Stock Exchange of India Limited Bombay Stock Exchange Limited Exchange Plaza, 5th Floor, Floor 1, Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers Plot No. C/l, G Block, Dalal Street Bandra-Kurla Complex, Bandra (East) Mumbai — 400001 Mumbai — 400051 Dear Sir, Please find enclosed a copy of Press Release regarding “Hon’ble Prime Minister dedicates to the Nation Phase 1 of ‘Pradhan Mantri Urja Ganga’ - Patna City Gas Distribution network also inaugurated” The above is for your information and record please. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, flit Shri A. K. Jha Company Secretary Encl.: As above Copy to: Deutsche Bank AG, Filiale Mumbai K/A- Ms. Aparna Salunke TSS & Global Equity Services The Capital, 14th Floor C-70, G Block, Bandra Kurla Complex Mumbai -40005 1 aim/ON L40200DL1984GOI018976 www.gailonline.com GAIL (India) Limited Hon’ble Prime Minister dedicates to the Nation Phase 1 of ‘Pradhan Mantri Urja Ganga’ Patna City Gas Distribution network also inaugurated Barauni (Bihar), February 17, 2019: Hon’ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi today dedicated to the — Nation the first — phase of the Jagdishpur Haldia & Bokaro Dhamra Natural Gas Pipeline Project (JHBDPL), popularly known as ‘Pradhan Mantri Urja Ganga’, and inaugurated the City Gas Distribution (CGD) network in Patna. -

Where Is This Self-Proclaimed Nationalism Coming From?

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Where is this Self-Proclaimed Nationalism Coming From? Kanhaiya Kumar's Speech in JNU KANHAIYA KUMAR Vol. 51, Issue No. 10, 05 Mar, 2016 Kanhaiya Kumar is the president of the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students Union (JNUSU). He was arrested on 13 February 2016 on charges of sedition and was granted a six-month interim bail on 2 March by the Delhi High Court. Jawaharlal Nehru University Students Union President Kanhaiya Kumar gave a speech in JNU after he was released from judicial custody on being granted a six month interim bail by the Delhi High Court. We reproduce an English translation of sections of his Hindi speech. From this platform on behalf of all of you, as JUNUSU president I take this opportunity of the media’s presence to thank and salute the people of this country. I want to thank all the people across the world, academicians and students, who have stood with JNU. I salute them (lal salaam). I have no rancour against anyone – none whatsoever against the ABVP [Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, student wing of the BJP]. You know why? (crowd roars – why?) Because the ABVP on our campus is actually more rational than the ABVP outside the campus. I have one suggestion for all those people who consider themselves political pundits – kindly watch the recording of the last presidential debate to see the state the ABVP candidate was reduced to. When we decimated the sharpest ABVP intellect there is in the country, which happens to be in the ABVP of JNU, you can draw your own conclusions about what awaits you in the rest of the country. -

Ljitof Cqmnctl Qf MRISTSRS· ()

• . 15·.:L·21l/11 >LJITOf CQMNCtL Qf MRISTSRS· () . (aa 011 OS.03.201 S) Shri Narendra·Modi Prime Minister and also in-charge of: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Department of Atomic Energy; Department of Space; and All important policy issues and all other portfolios not allocated to any Minister. CABINET MINISTERS 1. ·' Shri R~j Nath Singh Minister of Home Affairs. 2. Smt. Sushma Swaraj Minister of External Affairs . 3. .· Shri Arun Jaitley Minister of Finance; Minister of Corporate Affairs; and Minister of Information and Broadcasting. 4. Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu Minister of Urban Development; Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation; and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. 5. Shri Nitin Jairam Gadkari Minister of Road Transport and Highways; and Minister of Shipping. 6. Shri Manohar Parrikar Minister of Defence. 7. Shri Si.JreshPrabhu Minister of Railways. 8. Shri D.V. Sadananda Gowda Minister of Law and Justice. 9. Sushri UrnaBharatl Minister of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation. 10. Dr; Najma A. Heptulla Minister of Minority Affairs. 11. Shri Ramvilas Paswan Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. 12. Shri Kalraj Mishra Minister of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. 13. Smt. Maneka Sanjay Gandhi Minister of Women and Child Development. 14. Shri Ananthkumar Minister of Chemicals and Fertilizers. 15. Shri Ravi Shankar Prasad Minister of Communications and Information Technology. 16. Shri Jagat Prakash·Nadda Minister of Health and Family Welfare. 17. Shri Ashok Gajapathi Raju Minister of Civil Aviation. Pusapati 18. Shri Anant Geete Minister of •...--····~·- Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises. 19. Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal Minister of Food Processing Industries.