History of Fort Atkinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interstate 80 Lakes — Grand Island to Elm Creek

Interstate 80 Lakes — Grand Island to Elm Creek Fish Survey Results - Spring 2014 Brad Eifert, Fisheries Biologist Spanning a stretch of 150 miles along Interstate 80 from Grand Island to Hershey more than 60 small lakes are available for public fishing. Fisheries staff from the Kearney office has the management responsibility for the Interstate lakes located from Grand Island to Elm Creek. These man-made lakes, most of which were created for fill material when the Interstate system was developed in the 1960’s, range in size from 1 to 42 acres. The ground water fed lakes have excellent shoreline access for anglers and usually contain clear water and abundant aquatic vegetation, providing excellent habitat conditions for largemouth bass and bluegill. In addition, most of the lakes contain channel catfish, while others have crappie, rock bass, walleye, and northern pike. The fish populations are surveyed on a five year rotation and the following graphs and text display these results. Largemouth Bass Largemouth bass are present in all of the Interstate lakes in the central portion of Nebraska, with the exception of War Axe, which has been stocked with smallmouth bass. Lakes with high densities of smaller bass, include Windmill, Ft. Kearny, West and Middle Mormon Island, Kea Lake, Coot Shallows, and Sandy Channel #2. Lakes that traditionally produce larger bass include Cheyenne, Windmill #1, Bassway Strip, Blue Hole West, and Sandy Channel #8. Most of the I-80 lakes have a 15-inch minimum length limit on black bass. Exceptions include; Mormon Island SRA, Cheyenne, West Wood River, War Axe, and Archway Lakes, all of which have a 21-inch minimum length limit. -

Rabbit & Muskrat

Hnv`x,Nsnd,Lhrrntqh` Sq`chshnm`k Rsnqhdr 1 Aøwnid,Ihv«qd,Øÿs∂`¬gh V«j`ƒ The Ioway-Otoe-Missouria Traditional Stories The Ioway - Otoe-Missouria Tribes were at one time a single nation with the Winnebago (Hochank) in the area of the Great Lakes, and separated as a single group in the area of Green Bay, Wisconsin. They migrated southward through the area of Wisconsin and Minnesota to the Mississippi River. Those who became known as the Ioway remained at the junction of the Iowa River, while the rest of the band traveled on, further West and South to the Missouri River. At the fork of the Grand River, a quarrel ensued between the families of two chiefs, and the band of people divided into the Otoe and Missouria tribes. The two communities remained autonomous until the Missouria suffered near annihilation from sickness and intertribal warfare over hunting boundaries aggravated by the fur trade. The remnant group merged with the Otoes in 1798 under their chiefs. However, by the 1830’s they had been absorbed by the larger community. In the 1880’s, the leaders went South and selected lands between the Ponca and Pawnee in Oklahoma Territory. Their numbers had been reduced to 334 members. The oral tradition of the several communities had ceased, on the whole, by the early 1940’s, although several contemporary versions of stories and accompanying songs were recorded by this writer from the last fluent speakers in 1970 - 1987. The final two fluent speaker of Ioway - Otoe-Missouria language died at Red Rock, Oklahoma in the Winter of 1996. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

National Areas32 State Areas33

NEBRASKA : THE COR NHUSKER STATE 43 larger cities and counties continue to grow. Between 2000 and 2010, the population of Douglas County—home of Omaha—increased 11.5 percent, while neighboring Sarpy County grew 29.6 percent. Nebraska’s population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. The most significant growth has occurred in the Latino population, which is now the state’s largest minority group. From 2000 to 2010, the state’s Latino population increased from 5.5 percent to 9.2 percent, growing at a rate of slightly more than 77 percent. The black population also grew from 3.9 percent to 4.4 percent during that time. While Nebraska’s median age increased from 35.3 in 2000, to 36.2 in 2010 — the number of Nebraskans age 65 and older decreased slightly during the same time period, from 13.6 percent in 2000, to 13.5 percent in 2010. RECREATION AND PLACES OF INTEREST31 National Areas32 Nebraska has two national forest areas with hand-planted trees: the Bessey Ranger District of the Nebraska National Forest in Blaine and Thomas counties, and the Samuel R. McKelvie National Forest in Cherry County. The Pine Ridge Ranger District of the Nebraska National Forest in Dawes and Sioux counties contains native ponderosa pine trees. The U.S. Forest Service also administers the Oglala National Grassland in northwest Nebraska. Within it is Toadstool Geologic Park, a moonscape of eroded badlands containing fossil trackways that are 30 million years old. The Hudson-Meng Bison Bonebed, an archaeological site containing the remains of more than 600 pre- historic bison, also is located within the grassland. -

Catching up with the Cranes

Becoming an Outdoor Woman Program Catching up with the Cranes March 11, 2017 • Fort Kearny SRA Every year the Sandhill Cranes migrate through the bottleneck in central Nebraska on the way to their nesting grounds up north. Photography, local experts, waterfowl, wildlife, coffee, chili, and cranes all come together for an enjoyable day learning about these majestic birds. The Rainwater Basin and the North Platte River at Fort Kearny will be the viewing destinations to experience one of the largest migrations in the world. Schedule: 6 a.m. – Morning viewing at Fort Kearny Recreation Bridge 9 a.m. – Viewing at Rowe Sanctuary 11 a.m. – lunch and history of Fort Kearny State Historical Park 1 p.m. – Rainwater Basin tour Location: Fort Kearny State Recreation Area – South of Kearney Fee: $15/person plus state park permit PayPal or Check with registration form Prerequisites: Must be 16 years or older. To Bring: ❑ Warm clothing that isn’t bright ❑ Cameras that can have flash turned off ❑ Hiking boots (or other comfortable walking shoes) ❑ State park permit cut and mail Crane Viewing Trip Registration Form: NAME : _____________________________________________________________________ Registration form and fee are due by March 3, 2017. PHONE: _____________________________________________________________________ Refunds will only be issued if event is canceled. ADDRESS: ___________________________________________________________________ CITY: _______________________________________ STATE: ________ ZIP: ____________ Write checks to: E-MAIL: ______________________________________________________________________ Nebraska Game and Parks Foundation ALLERGIES: __________________________________________________________________ ____ participants X $15/ea. = $______ Mail registration form and check to: Additional information will be ❑ paid with paypal Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, sent to registered participants. 2200 N. 33rd Street, Lincoln, NE 68503-0370 call: Julia Plugge 402-471-6009 or e-mail: [email protected] 2016-56245 11/16af. -

The Western Services of Stephen Watts Kearny, 1815•Fi1848

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 21 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-1946 The Western Services of Stephen Watts Kearny, 1815–1848 Mendell Lee Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Taylor, Mendell Lee. "The Western Services of Stephen Watts Kearny, 1815–1848." New Mexico Historical Review 21, 3 (1946). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol21/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. ________STEPHEN_WATTS KEARNY NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VOL. XXI JULY, 1946 NO.3 THE WESTERN SERVICES OF STEPHEN WATTS KEARNY, 1815-18.48 By *MENDELL LEE TAYLOR TEPHEN WATTS KEARNY, the fifteenth child of Phillip and S. Susannah Kearny, was born at Newark, New Jersey, August 30, 1794. He lived in New Jersey until he matricu lated in Columbia University in 1809. While here the na tional crisis of 1812 brought his natural aptitudes to the forefront. When a call· for volunteers was made for the War of 1812, Kearny enlisted, even though he was only a few weeks away from a Bachelor of Arts degree. In the early part of the war he was captured at the battle of Queenstown. But an exchange of prisoners soon brought him to Boston. Later, for gallantry at Queenstown, he received a captaincy on April 1, 1813. After the Treaty of Ghent the army staff was cut' as much as possible. -

Nebraska Museums Association 7/7/11 6:17 PM

Nebraska Museums Association 7/7/11 6:17 PM Home Nebraska Museums About NMA Board of Directors History Membership Nebraska Museums Upcoming Events and Programs Publications Awards Exhibits for Travel Click on the region you are interested in to see the listing for that region. All regions have a printable list. Links (All museums/attractions listed in white with an asterisk are members of the Nebraska Museums Association.) Northeast (Click here for printable version.) Antelope County Historical Society 509 L Street, Hwy 275 Neligh, NE 68756 http://www.jailmuseum.net Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park * 86930 517 Avenue Royal, NE 68773 http://ashfall.unl.edu/ Elgin Historical Society 360 Park Street Elgin, NE 68636-0161 Neligh Mill State Historic Site N Street & Wylie Drive Neligh, NE 68756-0271 http://www.nebraskahistory.org/sites/mill/index.htm Orchard Historical Society 225 Windom Street Orchard, NE 68764 http://www.nebraskaandyou.com/OrchardPlanner.html Boone County Historical Society * 1025 W. Fairview Albion, NE 68620 Rae Valley Heritage Association 1249 State Hwy. 14 Petersburg, NE 68652 http://www.raevalley.org http://www.nebraskamuseums.org/NEMuseumsNortheast.shtml Page 1 of 5 Nebraska Museums Association 7/7/11 6:17 PM Butte Community Historical Center & Museum 721 First St., Butte, Nebraska 68722 http://buttenebraska.com/TourismandRecreation.html Naper Historical Society PO Box 72 Naper, NE 68755 http://www.angelfire.com/ks/phxbrd/NHS.html Burt County Museum, E.C. Houston House * 319 North 13th St. Tekamah, NE 68061-0125 http://www.huntel.net/community/burtcomuseum/ Swedish Heritage Center 301 North Chard Ave. Oakland, NE 68045 http://www.ci.oakland.ne.us/interest.asp Decatur Historical Committee and Robert E. -

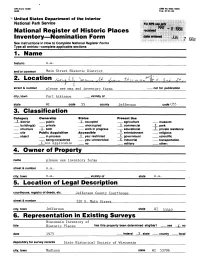

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-OO18 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type aM entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic n.a. and/or common Main Street Historic District 2. Location 5 street & number___please see map and inventory forms not for publication city, town Fort Atkinson vicinity of state WI code 55 county Jefferson code 055 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied _ X_ commercial _X_park structure X both work in progress _ y- educational X private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted X government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted _X_ industrial transportation X not applicable no military other: 4. Owner of Property name please see inventory forms street & number • n.a. city, town n.a. vicinity of state n.a, courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Jefferson County Courthouse street & number 320 S. Main Street city, town Jefferson state WI 53540, 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Wisconsin Inventory of title Historic Places nas tnis property been determined eligible? __ yes x no date 1975 federal X state __ county __ local depository for survey records State Historical Society of Wisconsin city, town Madison state WI 53706 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site _X_good ruins _JL_ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Note: The current district has 60 buildings. -

The Work of General Henry Atkinson, 1819-1842

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1937 In Defense of the Frontier: The Work of General Henry Atkinson, 1819-1842 Alice Elizbeth Barron Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Barron, Alice Elizbeth, "In Defense of the Frontier: The Work of General Henry Atkinson, 1819-1842" (1937). Master's Theses. 42. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/42 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1937 Alice Elizbeth Barron IN DErINSE or THE FRONTIER THE WORK OF GENERAL HDRl' ATKINSON, 1819-1842 by ALICE ELIZABETH BARROI( A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE or MASTER or ARTS 1n LOYOLA UNIVERSITY 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. A HISTORICAL SKETCH ............•..•.•.•• 1 First Indian Troubles Henry Atkinson's Preparation for the Frontier CHAPTER II. THE YELLOWSTONE EXPEDITION OF 1819 .••••.• 16 Conditions in the Upper Missouri Valley Calhoun's Plans The Expedition Building of Camp Missouri CHAPTER III. THE FIGHT FOR THE YELLOWSTONE EXPEDITION •• 57 Report on the Indian Trade The Fight for the Yellowstone Expedition Calhoun's Report - The Johnson Claims Events at Camp Missouri - Building ot Fort Atkinson The Attack on the War Department CHAPTER IV. -

Focus on Kiowa County Kiowa County Lies in the Southwestern Portion of Oklahoma

Oklahoma Ad Valorem FORUM Page 5 Focus on Kiowa County Kiowa County lies in the southwestern portion of Oklahoma. The area became part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The area’s history is rich in cultural encounters. The Doak’s Stand Treaty of 1820 gave all of southern Oklahoma to the Choctaw. In 1833 the Osage attacked a Kiowa camp near present Cooperton. The Osage decapitated the victims and left their heads in copper cooking pots for the returning Kiowa warriors to find. The Kiowa Kiowa County Courthouse, located in Hobart, OK. have since referred to the area as Cutthroat Gap. This incident, coupled with Choctaw complaints against the hostile Plains Indians, factored in the formation of a dragoon unit under the command of Gen. Henry Leavenworth and Col. Henry Dodge. The 1834 Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition met the Kiowa and Comanche at a Wichita village in Devil’s Canyon on the North Fork of the Red River. A peace treaty ensued. Located on Otter Creek near Mountain Park in 1858-59, Camp Radziminski operated as the northern extension of a line of forts across Texas to control and subdue the Plains Indians. By the end of the Red River War in 1875 the Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache had been confined to a reservation that encompassed present Kiowa County. As promised in the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, the government opened a boarding school six miles south of Gotebo at Rainy Mountain. The Rainy Mountain Boarding School existed from 1893 until 1920. The cattle industry of surrounding regions affected the area from the 1850s. -

Leavenworth, Kansas, 1827-2004

THE HISTORY OF WEATHER OBSERVING IN LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS, 1827-2004 Including Fort Leavenworth and West Leavenworth General Henry Leavenworth, 1783-1834 From History of Fort Leavenworth 1827-1927 Current as of January 21, 2005 Prepared by: Stephen R. Doty Information Manufacturing Corporation Rocket Center, West Virginia This report was prepared for the Midwestern Regional Climate Center under the auspices of the Climate Database Modernization Program, NOAA's National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, North Carolina Executive Summary Weather observing in the Leavenworth, Kansas, area began in 1827 when the U.S. Army established a post at Fort Leavenworth. Military surgeons recorded observations at the Post Hospital and the Military Prison Hospital until the early 1900’s. Observations were then begun at the Army Airfield in 1926 and they continued through 1996. Meanwhile, Smithsonian Institution observers were recording the weather in Leavenworth beginning in 1857. These volunteer observers were followed by the U.S. Army Signal Service and Weather Bureau observers serving through 1893. Volunteer observers again began to record Leavenworth’s weather. The U.S. Federal Penitentiary was the site of the observations beginning in 1911 continuing through 1946 when Kansas Power and Light assumed the observing role at their generating plant, a role they continued until 1961. Radio station KCLO was the site of the observations from 1961 until 1973. The site moved to the municipal water plant in 1973 where observations continued until 1988. After this time the program moved to a series of individuals, a service that continues to this day. An U.S. Army Signal Service volunteer observer recorded observations in West Leavenworth from 1883 until 1888. -

American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 Breakdown of Relations: American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957 Stephen R. Aoun Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5836 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Breakdown of Relations: American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University By Stephen Robert Aoun Bachelor of Arts, Departments of History and English, Randolph-Macon College, 2017 Director: Professor Gregory D. Smithers, Department of History, College of Humanities and Sciences, Virginia Commonwealth University Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Chapter One Western Expansion and Arikara Identity ………………………………………………. 17 Chapter Two Boarding Schools and the Politics of Assimilation ……...……………………………... 37 Chapter Three Renewing Arikara Identity