PROVINCIAL CLINICAL and PREVENTIVE SERVICES PLANNING for MANITOBA Doing Things Differently and Better

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

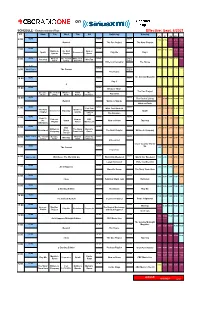

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

The Intended and Unintended Outcomes of New Governance Arrangements Within the NHS

SDO Project (08/1618/129) The intended and unintended outcomes of new governance arrangements within the NHS Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme March 2010 Professor John Storey, The Open University Business School Dr Richard Holti, The Open University Business School Dr Nik Winchester, The Open University Business School Professor Rod Green, Department of Management, The University of Bath Professor Graeme Salaman, The Open University Business School Professor Paul Bate, University College, London ____________________________________ Project Lead: Professor John Storey, Open University Business School Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA E-mail: [email protected] © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2010 1 SDO Project (08/1618/129) Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................5 Executive Summary....................................................6 Background ..............................................................................6 Aims........................................................................................6 About this study ........................................................................7 Key findings..............................................................................7 Conclusions ..............................................................................9 PART 1: POSITIONING THE STUDY...........................11 1 Introduction and background...........................11 1.1 The governance and -

Canada's Public Space

CBC/Radio-Canada: Canada’s Public Space Where we’re going At CBC/Radio-Canada, we have been transforming the way we engage with Canadians. In June 2014, we launched Strategy 2020: A Space for Us All, a plan to make the public broadcaster more local, more digital, and financially sustainable. We’ve come a long way since then, and Canadians are seeing the difference. Many are engaging with us, and with each other, in ways they could not have imagined a few years ago. Our connection with the people we serve can be more personal, more relevant, more vibrant. Our commitment to Canadians is that by 2020, CBC/Radio-Canada will be Canada’s public space where these conversations live. Digital is here Last October 19, Canadians showed us that their future is already digital. On that election night, almost 9 million Canadians followed the election results on our CBC.ca and Radio-Canada.ca digital sites. More precisely, they engaged with us and with each other, posting comments, tweeting our content, holding digital conversations. CBC/Radio-Canada already reaches more than 50% of all online millennials in Canada every month. We must move fast enough to stay relevant to them, while making sure we don’t leave behind those Canadians who depend on our traditional services. It’s a challenge every public broadcaster in the world is facing, and CBC/Radio-Canada is further ahead than many. Our Goal The goal of our strategy is to double our digital reach so that 18 million Canadians, one out of two, will be using our digital services each month by 2020. -

Course Title: Engl

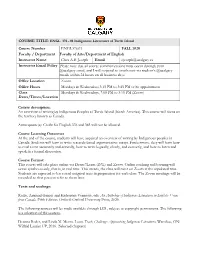

COURSE TITLE: ENGL 376 - 01 Indigenous Literatures of Turtle Island Course Number ENGL376.01 FALL 2020 Faculty / Department Faculty of Arts/Department of English Instructor Name Clara A.B. Joseph Email [email protected] Instructor Email Policy Please note that all course communications must occur through your @ucalgary email, and I will respond to emails sent via student’s @ucalgary emails within 24 hours on all business days. Office Location Zoom Office Hours Mondays & Wednesdays 3:15 PM to 3:45 PM or by appointment Class Mondays & Wednesdays, 2:00 PM to 3:15 PM (Zoom) Dates/Times/Location Course description: An overview of writing by Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island (North America). This course will focus on the territory known as Canada. Antirequisite(s): Credit for English 376 and 385 will not be allowed. Course Learning Outcomes At the end of the course, students will have acquired an overview of writing by Indigenous peoples in Canada. Students will learn to write research-based argumentative essays. Furthermore, they will learn how to read a text accurately and critically, how to write logically, clearly, and correctly, and how to listen and speak in a formal discussion. Course Format: This course will take place online via Desire2Learn (D2L) and Zoom. Online teaching and learning will occur synchronously, that is, in real time. This means, the class will meet on Zoom at the stipulated time. Students are expected to have read assigned texts in preparation for each class. The Zoom meetings will be recorded so that you can refer to them later. Texts and readings: Ruffo, Armand Garnet and Katherena Vermette, eds. -

Clinical Governance: the Next Hype?

Maltese Medical Journal, 2000; 12(1,2): 31 31 All rights reserved Clinical Governance: the next hype? Marie-Klaire Farrugia * *Senior House Officer, Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma Correspondence: Dr M K Farrugia, E-mail: [email protected] Introduction Evidence Based Practice The recent wave of strategies geared at improving the Evidence Based Practice is about basing one's quality of the NHS and combating medicolegal actions practice on the best accepted evidence to date. This in the UK has resulted in the accumulation of a number requires a basic infrastructure which will provide this of hyped-up terms, the latest of which is Clinical continuously-updated information. It entails information Governance. Clinical Governance is to be the main technology which will enable access to specialist vehicle for continuously improving the quality of databases such as the Cochrane Collaboration (www. patient care and developing the capacity to maintain cochrane.co.uk) and facilitated access to updated high standards. libraries4. As from June 1999, the British Health Act has placed a duty on each primary care trust and each NHS trust to Audit make arrangements for the purpose of monitoring and improving the quality of healthcare provided to patients. Assessing whether one's practice is actually up to the A recent update of the NHS Plan (www.nhs.uk! required standard relies on audit. All clinicians in the nationalplan/nhsplan.htm), published in July 2000, UK are now expected to participate in audit programs, explains how this move is to be governed by the and there is greater emphasis on evidence-based National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) practice and adherence to national frameworks and www.nice.org.uk - which will set standards and recommendations made by the NICE. -

MODEL CODE of PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Final Draft May 2016

MODEL CODE OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Final Draft May 2016 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________ The implementation of interjurisdictional mobility across Canada now allows lawyers to practice in every province and territory in the country. The importance of uniform national ethical standards was recognized by the Federation of Law Societies of Canada which began development of the Model Code of Conduct. The Model Code is the template for the Nunavut Code of Professional Conduct. Lawyers will find much familiar content preserving rules, commentaries and practical guidance previously found in the Canadian Bar Association Code which served Nunavut lawyers for many years. The Law Society of Nunavut created a mandate to review the Model Code with the objectives of maintaining uniformity and of making it consistent local law, practice and a distinct court system. A small resident bar practising in often distant locations meets many challenges. Resident and visiting lawyers may have difficulty accessing legal resources in remote settings. Challenges also include a diverse population speaking a number of languages, possessing unique cultures and variable economic resources. The Model Code is a work in progress. In future, Nunavut will benefit from the Federation’s continuing work and the ability to contribute to Model Code amendments. PREFACE One of the hallmarks of free and democratic society is the Rule of Law. Its importance is manifested in every legal activity in which citizens engage, from the sale of real property to the prosecution of murder to international trade. As participants in a justice system that advances the Rule of Law, lawyers hold a unique and privileged position in society. -

Spring 2014 FREE Parkways P Hoto by a Ndre W D Eel Next-Door Nature Explore Your Local Wildlife

Spring 2014 FREE PARKWAYS P hoto by by hoto A ndre w D eel NEXT-DOOR NATURE EXPLore your lOCal wildlife Wild TurkeYs feaTher Their NeSTs IT’s SPRINg! Time To GET OUTside WITh The kidS See pAge 6 See pAGEs 8–9 2 sAveSAV Ethe th EdATE DATE REMEMBEr tO SAVE thE DATE Be sure to mark your calendars for these upcoming Five Rivers MetroParks events! March 1 March 15 Miami vALLEy ST. PATRICK’S DAY GARDEning AT thE MARKET CONFERENCE 2nd Street Market Sinclair Community College April 17-19 April 19 EASTEr MEal ADOPt-a-PARK SHOPPING Various MetroPark 2nd Street Market Locations April 26 May 3-4 WILDFLOWEr anD ANNUal MAYFair NATIVE Plant SALE Plant SALE Cox Arboretum MetroPark Wegerzyn Gardens MetroPark May 8-10 May 9 MOTHER’S DAy URBan NIGHTS anD AT thE MARKET SILVEr FErn CAFÉ 2nd Street Market OPENS RiverScape MetroPark May 16 May 24 NAtional RIDE-thE-rivER BIKE To Work DAy RENTALS OPENS PANCAKE BREAKFAST RiverScape MetroPark RiverScape MetroPark For more information about these upcoming events or any of the programs and events offered by MetroParks each month, check the back section of this issue of ParkWays or visit www.metroparks.org METROPARKS.ORG (937) 275 PARK (7275) it’s our naTURE. THOUGHTs from becky 3 It’s Spring, MetroParks Friends, Everything is “greening up” around us — roots strengthening, shoots sprouting, branches extending. Nature’s activity serves as a perfect metaphor to remind me to keep identifying opportunities that will strengthen our resources and engage our community. This allows us to continue to protect our region’s natural heritage and provide outdoor experiences that inspire a personal connection with nature. -

GOVERNING MEDICINE Theory and Practice EDITED by Andrew Gray & Stephen Harrison G “Gray and Harrison Have Assembled an Impressive Array of Authors to Analyse The

GOVERNING MEDICINE Theory and Practice EDITED BY Andrew Gray & Stephen Harrison G “Gray and Harrison have assembled an impressive array of authors to analyse the changing role of the medical profession. The contributions range from historical OVERNING analyses of the relationship between government and doctors, to detailed examination of the implementation of clinical governance in the NHS. All offer important insights into an issue that lies at the heart of contemporary debates in health policy.” CHRIS HAM, PROFESSOR OF HEALTH POLICY AND MANAGEMENT, UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM This book brings together a range of detailed explorations of the theory, practice and prospects of clinical governance by some of the most eminent practitioners and researchers in the United Kingdom. Since New Labour’s institution of clinical governance through its White Paper in 1997, there has been a good deal of M debate about the history, theory and practice of clinical governance and the governance of clinical care. EDICINE Divided into three parts, the book focuses on the core areas of: N Medicine, Autonomy and Governance N Evidence, Science and Medicine N Realizing Clinical Governance Starting with the differing definitions of the term clinical governance, the contributors discuss the relationship of medicine and governance, the challenges that evidence-based medicine makes upon clinical practice and move on to suggest possible futures for clinical governance. Written by a team of experienced academics and practitioners, this book is aimed at reflective health professionals, as well as students and academics in the fields of health policy, health services management, social policy and public policy. Gray & Harrison Cover design Hybert Design GOVERNING Andrew Gray is Emeritus Professor of Public Sector Management and Visiting Professorial Fellow at the Centre for Clinical Management at the University of Durham. -

Clinical Governance Principles for Pharmacy Services 2018

Clinical Governance Principles for Pharmacy Services 2018 PSA Australia’s peak body for pharmacists © Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2018 This publication contains material that has been provided by the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA), and may contain material provided by the Commonwealth and third parties. Copyright in material provided by the Commonwealth or third parties belong to them. PSA owns the copyright in the publication as a whole and all material in the guide that has been developed by PSA. In relation to PSA owned material, no part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), or the written permission of PSA. Requests and inquiries regarding permission to use PSA material should be addressed to: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, PO Box 42, Deakin West ACT 2600. Where you would like to use material that has been provided by the Commonwealth or third parties, contact them directly. The development of the Clinical Governance Principles for Pharmacy Services has been funded by the Australian Government Department of Health. This work has been informed by experts, consultation and stakeholder feedback. The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) thanks all those involved in the development of this document and in particular, gratefully acknowledges the feedback and input received from the following organisations: • Australian Government Department of Health • Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care • The Society of Hospital Pharmacists -

Introduction to Clinical Governance – a Background Paper NO

INFORMATION SERIES NO. 1.1 Introduction to Clinical Governance – A Background Paper NO. 1.1 NO. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Office of Safety and Quality in Health Care acknowledges and appreciates the input of all individuals and groups who have contributed to the development of this background paper. In particular, the Office of Safety and Quality in Health Care would like to recognise the valuable contribution of members of the Western Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care for their guidance and support. The Office of Safety and Quality in Health Care will undertake further consultation with the metropolitan Area Health Services and Country Health Service Regions to ensure the implementation of the WA Clinical Governance policy at the local level. The Western Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care will provide a leadership role in monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the Policy by hospitals and health services across the Western Australian health system to ensure the delivery of consumer-focused, safe, quality health care in Western Australia. Table of Contents 1 CLINICAL GOVERNANCE: BACKGROUND PAPER 2 WHERE HAS CLINICAL GOVERNANCE COME FROM? 3 DO WE REALLY NEED CLINICAL GOVERNANCE? 3 1. THE VIEW FROM INSIDE 3 2. WHAT DOES THE PUBLIC SEE? 4 HOW ARE INTERNATIONAL HEALTH SYSTEMS RESPONDING? 5 WHAT DOES CLINICAL GOVERNANCE INCLUDE? 6 1. CLINICAL AUDIT 6 2. CLINICAL RISK MANAGEMENT 7 3. PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT 7 WHAT ARE THE BARRIERS? 8 CONCLUSION 9 Introduction to Clinical Governance 2 Clinical Governance: Background paper constantly strive to do their best for their patients, but in an imperfect and sometimes inadequate environment. -

1 the February 17, 2017, Winnipeg Event Was the First of Five Regional

The February 17, 2017, Winnipeg event was the first of five regional gatherings that will culminate in the convening of a national three-day conference in Ottawa. 101.5 UMFM streamed live online and archived the presentations from Winnipeg.1 Kathleen Buddle, Associate Professor of anthropology at the University of Manitoba and our local host, opened the discussion by saying that the goal of the event was to improve the Native Broadcasting Policy (CRTC 1990-89),2 which is up for review by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (the CRTC) this year. She then introduced elder Leslie Spillet3 who briefly spoke and facilitated the opening ceremony. The morning panel moderator Peter Kulchyski,4 professor from the University of Manitoba’s Native Studies, introduced the first presenters--CBC Unreserved’s Rosanna Deerchild and Kim Wheeler5. They spoke about the origins of their program, collaboration, and work to create the only all Indigenous- produced program airing nationally on CBC. Deerchild thanked Native Communications Inc (NCI FM)6 for her debut in radio broadcasting. Pointing to experiences of racism and silencing of Indigenous journalists within the CBC (also described later by Miles Morrisseau), Deerchild and Wheeler said they had to make their own Indigenous-produced spaces. When asked about the future of Indigenous broadcasting, Deerchild suggested that before reconciliation is possible, people need the truth. To do this work, Wheeler and Deerchild want Unreserved to evolve by going on the road to broadcast from Indigenous communities. Afterwards, Buddle provided a short review of Indigenous Peoples’ media activism to indigenize the media landscape and the limits of policymaking by the state of Canada. -

Clinical Governance

CLINICAL GOVERNANCE A STUDY OF IMPLEMENTATION; A STUDY OF CHANGE by LINDA ANN LATHAM A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Commerce and Social Science The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Health Services Management Centre University of Birmingham Birmingham B152TT February 2003 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. o ao (A) ABSTRACT The concept of clinical governance was first introduced to the National Health Service in the White Paper published in 1997 (Department of Health); it has been described as the 'linchpin' of the quality reforms and, as of April 1999, is one of the statutory duties placed on NHS Trust Boards. Clinical governance is defined as: 'A framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality if their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish.' (Department of Health, 1998; p33). The research project upon which this thesis is based took place over an 18 month period and has followed one NHS Trust as it implemented this new policy.