Bates Colostate 0053N 12800.Pdf (2.507Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis an Investigation Into Beaver-Induced Holocene

THESIS AN INVESTIGATION INTO BEAVER-INDUCED HOLOCENE SEDIMENTATION USING GROUND PENETRATING RADAR AND SEISMIC REFRACTION: BEAVER MEADOWS, ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK, COLORADO Submitted by Natalie Kramer Department of Geosciences In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2011 Master's Committee: Advisor: Ellen Wohl Co-Advisor: Dennis Harry Paul Meiman Copyright by Natalie Kramer 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT AN INVESTIGATION INTO BEAVER-INDUCED HOLOCENE SEDIMENTATION USING GROUND PENETRATING RADAR AND SEISMIC REFRACTION: BEAVER MEADOWS, ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK, COLORADO This study used ∼1 km of near-surface seismic refraction (SSR) data and ∼6 km of ground pene- trating radar (GPR) data to infer the impact of Holocene beaver activity on sediment aggradation in Beaver Meadows, Rocky Mountain National Park. GPR data were used to uniquely identify radar packages of genetically related strata corresponding to glacial, non-glacial, and beaver-induced sed- imentation. The radar package relating to glacial deposition was wedge-shaped and predominantly composed of a diffraction-rich, chaotic facie. The radar package relating to alluvium was draped over the glacial deposits and was characterized by multiple facies, but in general contained complex, slightly continuous reflectors interfingered with continuous, horizontal to subhorizontal reflectors. The radar package related to beaver-induced sedimentation was characterized by a laterally con- tinuous parallel facie, interpreted to be ponded sediment, that abruptly truncated into a zone of chaotic reflectors, interpreted to be a beaver dam. In order to determine the relative magnitude of post-glacial deposition, the bedrock contact was determined using seismic refraction, GPR, auger data, and previous seismic and drilling studies. -

To See the Hike Archive

Geographical Area Destination Trailhead Difficulty Distance El. Gain Dest'n Elev. Comments Allenspark 932 Trail Near Allenspark A 4 800 8580 Allenspark Miller Rock Riverside Dr/Hwy 7 TH A 6 700 8656 Allenspark Taylor and Big John Taylor Rd B 7 2300 9100 Peaks Allenspark House Rock Cabin Creek Rd A 6.6 1550 9613 Allenspark Meadow Mtn St Vrain Mtn TH C 7.4 3142 11632 Allenspark St Vrain Mtn St Vrain Mtn TH C 9.6 3672 12162 Big Thompson Canyon Sullivan Gulch Trail W of Waltonia Rd on Hwy A 2 941 8950 34 Big Thompson Canyon 34 Stone Mountain Round Mtn. TH B 8 2100 7900 Big Thompson Canyon 34 Mt Olympus Hwy 34 B 1.4 1438 8808 Big Thompson Canyon 34 Round (Sheep) Round Mtn. TH B 9 3106 8400 Mountain Big Thompson Canyon Hwy 34 Foothills Nature Trail Round Mtn TH EZ 2 413 6240 to CCC Shelter Bobcat Ridge Mahoney Park/Ginny Bobcat Ridge TH B 10 1500 7083 and DR trails Bobcat Ridge Bobcat Ridge High Bobcat Ridge TH B 9 2000 7000 Point Bobcat Ridge Ginny Trail to Valley Bobcat Ridge TH B 9 1604 7087 Loop Bobcat Ridge Ginny Trail via Bobcat Ridge TH B 9 1528 7090 Powerline Tr Boulder Chautauqua Park Royal Arch Chautauqua Trailhead by B 3.4 1358 7033 Rgr. Stn. Boulder County Open Space Mesa Trail NCAR Parking Area B 7 1600 6465 Boulder County Open Space Gregory Canyon Loop Gregory Canyon Rd TH B 3.4 1368 7327 Trail Boulder Open Space Heart Lake CR 149 to East Portal TH B 9 2000 9491 Boulder Open Space South Boulder Peak Boulder S. -

5-10-2021 Evening Meeting Packet

E1 Town of Grand Lake Board of Trustees Workshop & Meeting The Town of Grand Lake upholds the Six Pillars of Character: Citizenship, Trustworthiness, Respect, Responsibility, Fairness and Caring 5-10-2021 Board of Trustee Workshop & Evening Meeting This Virtual Meeting will be streamed live online Please join my meeting from your computer, tablet, or smartphone. https://www.gotomeet.me/JennThompson/grand-lake-board-of-trustee-workshop--evening-me-5 You can also dial in using your phone. United States: +1 (646) 749-3122 Access Code: 404-998-853 New to GoToMeeting? Get the app now and be ready when your first meeting starts: https://global.gotomeeting.com/install/404998853 Monday May 10, 2021 – Work Session 4:30 PM ________________________________________________________ 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call 3. Conflicts of Interest 4. Request for Economic Development Funds – Ken Wright 5. Grand County Housing Authority – Sheena Darland 6. Chamber of Commerce Presentation – Emily Hagen 7. Board of Trustee Committee Assignments Monday May 10, 2021 – Evening Meeting 6:00 PM _____________________________________________________ A. Call to Order B. Pledge of Allegiance C. Announcements D. Roll Call E. Conflicts of Interest F. Public Comments (limited to 3 minutes) G. Meeting Minutes – Consideration to approve meeting minutes dated April 26, 2021 (Pg. E2) H. Financial – Consideration to approve Accounts Payable for May 2021 (Pg. E7) I. Consideration of Resolution 13-2021, a Resolution to Allow an Accessory Structure on a Vacant Lot located at Subdivision: Coker’s Corner Minor Subdivision Lot: A&B, More Commonly Referred to as 1670 Sunnyside Drive (Pg. E13) J. Consideration of a Motion to Recommend a Consultant for the Municipal Lands Master Plan Contract (Pg. -

Appendix C Table 1, Camp Area Summary

Backcountry/Wilderness Management Plan and Environmental Assessment Appendix C Appendix C Table 1, Camp Area Summary Designated Areas/Sites Individual Camp Areas Campsites People East Side 60 109 763 West Side 59 88 616 Total 119 197 1379 Group Camp Areas Campsites People East Side 10 10 120 West Side 11 11 132 Total 21 21 252 Accessible Camp Areas Campsites People East Side 1 1 12 West Side 0 0 0 Total 1 1 12 Wood Fire Camp Areas Campsites East Side 8 13 West Side 9 13 Total 17 26 Stock Areas/Sites Individual Camp Areas Campsites People Stock East Side 3 3 18 24 West Side 3 3 18 24 Total 6 6 36 48 Group Camp Areas Campsites People Stock East Side 2 2 24 32 West Side 2 2 24 32 Total 4 4 48 64 Llama only Camp Areas Campsites People Stock East Side 2 2 14 10 West Side1175 Total 3 3 21 15 Wood Fire Camp Areas Campsites East Side 8 13 West Side 9 13 Total 17 26 Rocky Mountain National Park C-1 Backcountry/Wilderness Management Plan and Environmental Assessment Appendix C Crosscountry Areas Areas Parties People East Side 9 16 112 West Side 14 32 224 Total 23 48 336 Summer Totals for Designated, Stock and Crosscountry Areas Camp Areas Campsites/Parties People East Side 80 136 1004 West Side 84 131 969 Total 164 267 1973 Bivouac Areas Areas People East Side 11 88 West Side 0 0 Total 11 88 Winter Areas Areas Parties People East Side 32 136 1632 West Side 23 71 852 Total 55 207 2484 Rocky Mountain National Park C-2 Backcountry/Wilderness Management Plan and Environmental Assessment Appendix C Appendix C Table 2, Designated Camp Area/Sites Number -

Rocky Mountain National Park News U.S

National Park Service Rocky Mountain National Park News U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper of Rocky Mountain National Park Summer - 2013 July 19 - September 2 2nd Edition Bear Lake Road Reconstruction continues. Expect up to two, 20 minute delays in each direction between Moraine NPS/Ann Schonlau Park Visitor Center and the Park & Ride. Welcome to Your Park! Visitor Centers Rocky Mountain National Park is a special place in the hearts of many people. These mountains are home to flowers, forests and wildlife. For East of the Divide – Estes Park Area generations, this place has nourished the human spirit and connected us to the natural world. We invite you to explore your park, make your own Alpine Visitor Center memories, and discover what Rocky means to you. Enjoy it, protect it Open daily 9 a.m.-5 p.m. (weather permitting) Features extraordinary views of alpine tundra, displays, information, and be safe out there. bookstore, adjacent gift shop, cafe, and coffee bar. Call (970) 586-1222 for The Staff of Rocky Mountain National Park Trail Ridge Road conditions. Beaver Meadows Visitor Center Looking for Fun? Open daily 8 a.m.- 6 p.m. Features spectacular free park movie, Rocky Mountain National Park has something for everyone! Make information, bookstore, large park orientation your trip memorable with these tips: map, and backcountry permits in an adjacent building. Be inspired – How many times can you say, “Wow!” Find out by driving Fall River Visitor Center Alpine Visitor Center up Trail Ridge Road for spectacular views. Open daily 9 a.m.-5 p.m. -

State of the Park Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior State of the Park Report Rocky Mountain National Park Colorado December 2017 National Park Service. 2017. State of the Park Report for Rocky Mountain National Park. State of the Park Series No. 50. National Park Service, Washington, DC. On the cover: Hallett Peak reflected in Dream Lake. NPS Photo. Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infrastructure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non-quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. Executive Summary The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of national parks for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. NPS Management Policies (2006) state that “The Service will also strive to ensure that park resources and values are passed on to future generations in a condition that is as good as, or better than, the conditions that exist today.” As part of the stewardship of national parks for the American people, the NPS has begun to develop State of the Park reports to assess the overall status and trends of each park’s resources. -

Rocky Mountain National Park Trail System

Rocky Mountain National Park Trail Map HOURGLASS RESERVIOR Rocky M4ountain National Park Trail System 1 TRAP LAKE Y TWIN LAKE RESERVIOR W PETERSON LAKE H JOE WRIGHT RESERVIOR O L O C ZIMMERMAN LAKE MIRROR LAKE R E P P U , S S A P Y M Corral Creek USFS Trail Head M (! U M LAKE HUSTED 4 HWY 1 LOST LAKE COLO PPER LAKE LOUISE LOST LAKE, U #*Lost Falls Rowe Mountain LAKE DUNRAVEN LOST LAKE 13184 , LOWER Dunraven USFS Trail Head LONG DRAW RESERVIOR D (! Rowe Peak 13404 Hagues PeaDk 13560 D MICHIGAN LAKES TH LAKE AGNES E S SNOW LAKE La Poudre Pass Trail Head AD Mummy Mountain (! DL E 13425 D Fairchild Mountain 13502 D CRYSTAL LAKE LAWN LAKE TH UN Ypsilon Mountain DE R 13514 PA B SS D L A C R K PE C P SPECTACLE LAKES A , U N ER Chiquita, Mount Y IV D O R ST 13069 N E WE , DR IL U U A Y P O 4 TR P P P 3 TE Chapin Pass Trail Head S E Bridal Veil Falls LAKE OF THE CLOUDS Y U (! IL W O R #* H S N ER Cow Creek Trail Head U L K, LOW (! R A REE K OW C E C E V C(!rater Trail Head I (! U R POUDRE LAKE Cache La Poudre Trail Head S H O (! W D Milner Pass Trail Head Chasm Falls Y A #* R 3 Horseshoe Falls 4 Rock Cut Trail Head O ! #* L ( Thousand Falls O #* C Lawn Lake Trail Head FAN LAKE (! Colorado River Trail Head SHEEP LAKES (! Timber Lake Trail Head (! Beaver Ponds Trail Head (! CASCADE LAKE HIDDEN VALLEY BEAVER PONDS Lumpy Ridge Trail Head Ute Crossing Trail Head (! (! FOREST LAKE Deer Mountain/ Deer Ridge Trail Head ARROWHEAD LAKE ROCK LAKE (! U TE T TOWN OF RA LAKE ESTES IL Never Summer Trail Head INKWELL LAKE EA ESTES PARK (! ST U Upper Beaver Meadows -

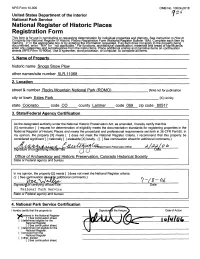

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This~____, ,.,,. Form Is for ., ,.. ....„

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior 7 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This~____,_,.,,._ form is for .,_,.._....„......,_ use in nominating »,,,.^,. or requesting „._»._ determination „.,,._ for individual...... K,Kproperties . irBuand ||districts.etjn 16A Seex Comp instruction|eteeach in itembyHow to does not apply to the property being ~ materials and areas of significance, sheetsenter only (NPS categories Form 10-900a).'' and subcategories ------- from the --.instructions. - Place....................... additional entries and ....narrative items on continuation Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Snogo Snow Plow other names/site number SLR. 11068 2. Location street & number Rocky Mountain National Park (ROMO)___________ [N/A] not for publication city or town Estes Park________________________________ [x\ vicinity state Colorado___ code CO county Larimer code 069 zip code 80517 3. State/Federal Agency Certification_______________________________ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [X] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ ] statewide [X] locally. ([ ] See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Historic Preservation Officer_ Signature of co-certifying official/Title / \ /1 Date Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Colorado Historical Society State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property [X] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Black Canyon of the Gunnison Great Sand Dunes Mesa Verde Rocky

COLORADO NATIONAL PARK TRIP PLANNER Black Canyon of the Gunnison Great Sand Dunes Mesa Verde Rocky Mountain TOP 4 ROAD TRIPS 14 Cody Dinosaurs and Deserts Thermopolis GETTING Wildlife and Natural Wonders 120 Best of Colorado Loop Idaho Land of Enchantment Falls 26 THERE Lander Dinosaur National Monument Plan your dream vacation Laramie with our top routes to Colorado’s national parks and monuments. Grand Estes Park 40 Lake Learn more at Steamboat Lyons 40 Glenwood Springs MyColoradoParks.com. Springs 133 Delta Cripple Creek Colorado National Montrose Monument Park and Preserve. For 25 BEST OF a unique wildlife 550 Great Sand Dunes COLORADO LOOP experience, drive east National Park 160 Alamosa and Preserve from Denver to Pagosa Miles 1,130 Springs Keenesburg to visit The Farmington The ultimate Colorado Wild Animal Sanctuary, road trip includes home to more than 450 550 Taos 25 Bandelier charming mountain rescued tigers, lions, National Monument towns, hot springs, wolves and bears. Santa Fe desert scenery and impressive peaks. Head straight to Rocky DINOSAURS Mountain National Park AND DESERTS from Denver and take Trail Ridge Road west Miles 1,365 to Grand Lake. Soak in Go from red-rock the pools of Hot canyons to alpine Phoenix Sulphur Springs before meadows on this loop. heading to Winter Park Abilene Start in Salt Lake City Carlsbad Caverns and Dillon. Stop in National Park and drive southeast to Glenwood Springs to Vernal, Utah, the experience the town’s Flaming Gorge National Map by Peter Sucheski legendary hot springs Recreation Area and and adventure park. Just south you’ll find with New Mexican stunning San Luis Dinosaur National Continue west to the WILDLIFE AND Grand Teton National deserts on this Valley. -

A Guide to the Geology of Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

A Guide to the Geology of ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK COLORADO For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 15 cents A Guide to the Geology of ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK [ COLORADO ] By Carroll H. Wegemann Former Regional Geologist, National Park Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HAROLD L. ICKES, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . NEWTON B. DRURY, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1944 Table of Contents PAGE INTRODUCTION in BASIC FACTS ON GEOLOGY 1 THE OLDEST ROCKS OF THE PARK 2 THE FIRST MOUNTAINS 3 The Destruction of the First Mountains 3 NATURE OF PALEOZOIC DEPOSITS INDICATES PRESENCE OF SECOND MOUNTAINS 4 THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS 4 Time and Form of the Mountain Folding 5 Erosion Followed by Regional Uplift 5 Evidences of Intermittent Uplift 8 THE GREAT ICE AGE 10 Continental Glaciers 11 Valley Glaciers 11 POINTS OF INTEREST ALONG PARK ROADS 15 ROAD LOGS 18 Thompson River Entrance to Deer Ridge Junction 18 Deer Ridge Junction to Fall River Pass via Fall River .... 20 Fall River Pass to Poudre Lakes 23 Trail Ridge Road between Fall River Pass and Deer Ridge Junction 24 Deer Ridge Junction to Fall River Entrance via Horseshoe Park 29 Bear Lake Road 29 ILLUSTRATIONS LONGS PEAK FROM BEAR LAKE Front and back covers CHASM FALLS Inside back cover FIGURE PAGE 1. GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE iv 2. LONGS PEAK FROM THE EAST 3 3. PROFILE SECTION ACROSS THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS 5 4. ANCIENT EROSIONAL PLAIN ON TRAIL RIDGE 6 5. ANCIENT EROSIONAL PLAIN FROM FLATTOP MOUNTAIN ... 7 6. VIEW NORTHWEST FROM LONGS PEAK 8 7. -

Rocky Mountain National Park High Country Headlines

Rocky Mountain National Park HIGH COUNTRY HEADLINES Winter 2006-07 October 29 - March 30 Your Park in Winter Reflected sunlight sparkles in the snow. Tracks of tiny mice and great elk cross INSIDE your trail. Frozen alpine lakes ringed 2 You Need to Know by massive peaks can be reached by snowshoe, ski, and even on foot. For 3 Survival those who are prepared, winter in Rocky Mountain National Park is a beautiful time 4 Ranger-led Programs full of crisp adventures. 5 Camping 6-7 Winter Tours 8 Park Map The park’s west side holds the best snow. photo: Harry Canon This newspaper is designed to help you most of the winter. Easy trails head toward drifts, Trail Ridge Road is too dangerous comfortably and safely enjoy this high Lulu City or Sun Valley, and many more to try to keep fully open through the and wild park during its longest season. challenging options are also available. On winter. Yet much of the park is still open Information on visitor centers, important the east side of the park (Estes Park area), year-round. You can drive to magnificent phone numbers, winter travel, and snowshoeing is more reliable than cross- view areas like Many Parks Curve and recreation are on pages 2 and 3. Free country skiing. The lofty peaks of Rocky Bear Lake on the east, and through the ranger-led programs are listed on page 4. Mountain National Park tend to catch and spectacular Kawuneeche Valley on the Camping is described on page 5. Some hold more snow on their western slopes west. -

Rocky Mountain National Park Hikes for Families with Ratings 0 1,000 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000

Rocky Mountain National Park Trail Map Corral Creek USFS Trail Head Rocky Moun!(tain National Park Hikes for Families LAKE HUSTED LOST LAKE LAKE LOUISE Lost Falls #* Rowe Mountain LAKE DUNRAVEN 13184 Dunraven USFS Trail Head LONG DRAW RESERVIOR D !( Rowe Peak 13404 D Hagues Peak 13560 D La Poudre Pass Trail Head !( Mummy Mountain 13425 D Fairchild Mountain 13502 D CRYSTAL LAKE LAWN LAKE Ypsilon Mountain 13514 D SPECTACLE LAKES Chiquita, Mount D 13069 34 Y W H S Crater Bighorn Family Hike U Chapin Pass Trail Head Bridal Veil Falls !( #* Cow Creek Trail Head !( Cache La Poudre Trail Head Crater Trail Head !( !( Horseshoe Falls Family Hike POUDRE LAKE !( Milner Pass Trail Head Chasm Falls #* Horseshoe Falls Rock Cut Trail Head #* !( Thousand Falls #* Lake Irene Family Hike Lawn Lake Trail Head FAN LAKE !( SHEEP LAKES !( !( Beaver Ponds Trail Head !( CASCADE LAKE HIDDEN VALLEY BEAVER PONDS Lumpy Ridge Trail Head !( Ute Crossing Trail Head U !( S HW FOREST LAKE Beaver Ponds Family Hike Y 34 Deer Mountain/ Deer Ridge Trail Head ARROWHEAD LAKE ROCK LAKE !( TOWN OF LAKE ESTES ESTES PARK INKWELL LAKE !( Upper Beaver Meadows Trail Head AZURE LAKE !( TROUT FISHING POND (ARTIFICIAL US HWY 36 US H 7 WY 36 Y W H O L Cub Lake Trail Head O !( !( Fern Lake Trail Head C !( Fern Falls Family Hike HOURGLASS LAKE Fern Falls #* CUB LAKE !( Hallowell Park Trail Head Marguerite Falls !( #* ODESSA LAKE BIERSTADT LAKE East Portal Trail Head Sprague Lake Family Hike !( Grace Falls #* Sprague Lake Trail Head !( !( Bear Lake Family Hike Bierstadt Lake Trail Head