Schizophrenia an Information Guide Revised Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural and Collective Interpretations of Regular Marijuana Use Impact on Work and School Performance: an Ethnographic Inquiry

DRAFT: Please do not quote or cite without permission of author s Cultural and Collective Interpretations of Regular Marijuana Use Impact on Work and School Performance: An Ethnographic Inquiry Jan Moravek, Bruce D. Johnson, Eloise Dunlap National Development and Research Institutes, New York Abstract Objective: To compare users’ reports on how their cannabis consumption affects their work and school performance with relevant cultural narratives. Methods: Ninety-two regular marijuana smokers were interviewed in New York City. A qualitative content analysis of the in-depth interviews was juxtaposed with prevalent cultural and collective stories about the effects of marijuana use. Results : Cannabis users reported positive effects in reducing work-related stress, energizing the mind, or enhancing creativity. Negative effects included difficult concentration, memory damage, and lack of motivation or “laziness”. Some discussed preventing adverse effects and resultant job performance losses by avoiding smoking before work or “controlling the high” while at work, yet others depicted negative consequences as unavoidable. Conclusions: Marijuana users spoke in both terms of mainstream narratives (the amotivational syndrome, irresponsible use), and in contrasting collective narratives (glamorizing marijuana as having positive effects on work performance or no relevant consequences, and constructing use as controllable). Introduction In this paper we focus upon the perceived impact of marijuana consumption on work and school performance. Analysis will examine experiences over time from the perspective of marijuana consumers. 1 DRAFT: Please do not quote or cite without permission of author s We explore the variety of experiences informants have had when they have smoked marijuana and gone to their jobs or their classrooms. -

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

“Cat-Gras” Delusion: a Unique Misidentification Syndrome and a Novel Explanation

Neurocase The Neural Basis of Cognition ISSN: 1355-4794 (Print) 1465-3656 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nncs20 “Cat-gras” delusion: a unique misidentification syndrome and a novel explanation R. Ryan Darby & David Caplan To cite this article: R. Ryan Darby & David Caplan (2016) “Cat-gras” delusion: a unique misidentification syndrome and a novel explanation, Neurocase, 22:2, 251-256, DOI: 10.1080/13554794.2015.1136335 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2015.1136335 Published online: 14 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1195 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=nncs20 Download by: [Vanderbilt University Library] Date: 06 December 2017, At: 06:39 NEUROCASE, 2016 VOL. 22, NO. 2, 251–256 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2015.1136335 “Cat-gras” delusion: a unique misidentification syndrome and a novel explanation R. Ryan Darbya,b,c and David Caplana,c aDepartment of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; bDepartment of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; cHarvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA ABSRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Capgras syndrome is a distressing delusion found in a variety of neurological and psychiatric diseases Received 23 June 2015 where a patient believes that a family member, friend, or loved one has been replaced by an imposter. Accepted 20 December 2015 Patients recognize the physical resemblance of a familiar acquaintance but feel that the identity of that KEYWORDS person is no longer the same. -

Paranoia and Slowed Cognition Ijeoma Ijeaku, MD, MPH, and Melissa Pereau, MD

Cases That Test Your Skills Paranoia and slowed cognition Ijeoma Ijeaku, MD, MPH, and Melissa Pereau, MD Mr. K, age 45, is paranoid, combative, and agitated. Two weeks How would you ago he sustained chemical abrasions at home. What could be handle this case? Visit CurrentPsychiatry.com causing his altered mental status? to input your answers and see how your colleagues responded CASE Behavioral changes aggressive and combative. He throws chairs at Mr. K, age 45, is brought to the emergency de- his peers and staff on the unit and is placed in partment (ED) by his wife for severe paranoia, physical restraints. He requires several doses combative behavior, confusion, and slowed of IM haloperidol, 5 mg, lorazepam, 2 mg, and cognition. Mr. K tells the ED staff that a chemi- diphenhydramine, 50 mg, for severe agitation. cal abrasion he sustained a few weeks earlier Mr. K is guarded, perseverative, and selectively has spread to his penis, and insists that his mute. He avoids eye contact and has poor penis is retracting into his body. He has tied grooming. He has slow thought processing and a string around his penis to keep it from dis- displays concrete thought process. Prednisone appearing into his body. According to Mr. K’s is discontinued and olanzapine, titrated to 30 wife, he went to an urgent care clinic 2 weeks mg/d, and mirtazapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, are ago after he sustained chemical abrasions started for psychosis and depression. from exposure to cleaning solution at home. Mr. K’s mood and behavior eventually re- The provider at the urgent care clinic started turn to baseline but slowed cognition persists. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

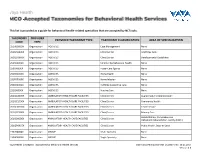

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

The Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders Bob Boland MD Slide 1

The Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders Bob Boland MD Slide 1 Psychotic Disorders Slide 2 As with all the disorders, it is preferable to pick Archetype one “archetypal” disorder for the category of • Schizophrenia disorder, understand it well, and then know the others as they compare. For the psychotic disorders, the diagnosis we will concentrate on will be Schizophrenia. Slide 3 A good way to organize discussions of Phenomenology phenomenology is by using the same structure • The mental status exam as the mental status examination. – Appearance –Mood – Thought – Cognition – Judgment and Insight Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders. Slide 4 Motor disturbances include disorders of Appearance mobility, activity and volition. Catatonic – Motor disturbances • Catatonia stupor is a state in which patients are •Stereotypy • Mannerisms immobile, mute, yet conscious. They exhibit – Behavioral problems •Hygiene waxy flexibility, or assumption of bizarre • Social functioning – “Soft signs” postures as most dramatic example. Catatonic excitement is uncontrolled and aimless motor activity. It is important to differentiate from substance-induced movement disorders, such as extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Slide 5 Disorders of behavior may involve Appearance deterioration of social functioning-- social • Behavioral Problems • Social functioning withdrawal, self neglect, neglect of • Other – Ex. Neuro soft signs environment (deterioration of housing, etc.), or socially inappropriate behaviors (talking to themselves in -

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia The upcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) makes several key changes to the category of schizophrenia and highlights for future study an area that could be critical for early detection of this often debilitating condition. Changes to the Diagnosis Schizophrenia is characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and behavior, and other symptoms that cause social or occupational dysfunction. For a diagnosis, symptoms must have been present for six months and include at least one month of active symptoms. DSM-5 raises the symptom threshold, requiring that an individual exhibit at least two of the specified symptoms. (In the manual’s previous editions, that threshold was one.) Additionally, the diagnostic criteria no longer identify subtypes. Subtypes had been defined by the predominant symptom at the time of evaluation. But these were not helpful to clinicians because patients’ symptoms often changed from one subtype to another and presented overlapping subtype symptoms, which blurred distinc- tions among the five subtypes and decreased their validity. Some of the subtypes are now specifiers to help provide further detail in diagnosis. For example, catatonia (marked by motor immobility and stupor) will be used as a specifier for schizophrenia and other psychotic conditions such as schizoaffec- tive disorder. This specifier can also be used in other disorder areas such as bipolar disorders and major depressive disorder. Area for Further Study Attenuated psychosis syndrome is included in Section III of the new manual; conditions listed there require further research before their consideration as formal disorders. This potential category would identify a person who does not have a full-blown psychotic disorder but exhibits minor versions of relevant symptoms. -

Association Between Schizophrenia Polygenic Score and Psychotic Symptoms In

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/528802; this version posted January 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Association between schizophrenia polygenic score and psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: meta-analysis of 11 cohort studies. Byron Creese1,2*, Evangelos Vassos3*, Sverre Bergh2,4,5*, Lavinia Athanasiu6,7, Iskandar Johar8,2, Arvid Rongve9,10,,2, Ingrid Tøndel Medbøen5,11, Miguel Vasconcelos Da Silva1,8,2, Eivind Aakhus4, Fred Andersen12, Francesco Bettella6,7 , Anne Braekhus5,11,13, Srdjan Djurovic10,14, Giulia Paroni16, Petroula Proitsi17, Ingvild Saltvedt18,19, Davide Seripa16, Eystein Stordal20,21, Tormod Fladby22,23, Dag Aarsland2,8,24, Ole A. Andreassen6,7, Clive Ballard1,2*, Geir Selbaek4,5,25*, on behalf of the AddNeuroMed consortium and the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative** 1. University of Exeter Medical School, Exeter, UK 2. Norwegian, Exeter and King's College Consortium for Genetics of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia 3. Social Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London 4. Research centre of Age-related Functional Decline and Disease, Innlandet Hospital Trust, Pb 68, Ottestad 2312, Norway 5. Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Ageing and Health, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Tønsberg, Norway 6. NORMENT, Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. 7. NORMENT, Division of Mental Health and Addiction, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway 8. Department of Old Age Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London 9. -

Psychotic Symptoms in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: a Case Illustration and Literature Review

CASE REPORT SA Psych Rev 2003;6: 21-24 Psychotic symptoms in post traumatic stress disorder: a case illustration and literature review Adekola O Alao, Laura Leso, Mantosh J Dewan, Erika B Johnson Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY, USA ABSTRACT Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition being increasingly recognized. The diagnosis is based on the re-experiencing of a traumatic event. There have been reports of the presence of psychotic symptoms in some cases of PTSD. This may represent in- creased severity or a different diagnostic clinical entity. It has also been suggested that psychotic symptoms may be over-represented in the Hispanic population. In this manuscript, we describe a case to illustrate this relationship and we review the current literature on the relationship of psychotic symptoms among PTSD patients. The implications regarding diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis are discussed. Keywords: Psychosis; PTSD; Trauma; Hallucinations; Delusions; Posttraumatic stress disorder. INTRODUCTION the best of our knowledge is the first report of psychotic symp- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric illness for- toms in a non-veteran adult with PTSD. mally recognized with the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric CASE ILLUSTRATION Association in 1980.1 Re-experiencing of traumatic events as A 37 year-old gentleman was admitted to a state university hos- recurrent unpleasant images, nightmares, and intrusive feelings pital inpatient setting after alerting his wife of his suicidal is a core characteristic of PTSD.2 Most PTSD research has oc- thoughts and intent to slit his throat with a kitchen knife.