What's Trending in Children's Literature and Why It Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Writing a Thesis Or Dissertation

GUIDELINES FOR WRITING A THESIS OR DISSERTATION CONTENTS: Guidelines for Writing a Thesis or Dissertation, Linda Childers Hon, Ph.D. Outline for Empirical Master’s Theses, Kurt Kent, Ph.D. How to Actually Complete A Thesis: Segmenting, Scheduling, and Rewarding, Kurt Kent, Ph.D. How to Make a Thesis Less Painful and More Satisfying (by Mickie Edwardson, Distinguished Professor of Telecommunication, Emeritus, ca. 1975), provided by Kurt Kent 2007-2008 Guidelines for Writing a Thesis or Dissertation Linda Childers Hon Getting Started 1. Most research begins with a question. Think about which topics and theories you are interested in and what you would like to know more about. Think about the topics and theories you have studied in your program. Is there some question you feel the body of knowledge in your field does not answer adequately? 2. Once you have a question in mind, begin looking for information relevant to the topic and its theoretical framework. Read everything you can--academic research, trade literature, and information in the popular press and on the Internet. 3. As you become well-informed about your topic and prior research on the topic, your knowledge should suggest a purpose for your thesis/dissertation. When you can articulate this purpose clearly, you are ready to write your prospectus/proposal. This document specifies the purpose of the study, significance of the study, a tentative review of the literature on the topic and its theoretical framework (a working bibliography should be attached), your research questions and/or hypotheses, and how you will collect and analyze your data (your proposed instrumentation should be attached). -

J-Beginning-Chapter-Books.Pdf

Children’s Juvenile Striker Assist by Jake Maddox Pewaukee Public Library Fiction Books (GR– P/Lexile 590) How to be a Perfect Person in These titles can by found in the Juvenile Fiction Collection Just Three Days by Stephen Manes Beginning organized alphabetically by the (GR– N/ Lexile 720) author’s last name. Judy Moody by Megan McDonald Chapter (GR– M/ Lexile 530) Ivy and Bean by Annie Barrows (GR– M/Lexile 510) Lulu by Hilary McKay Books (GR-N/Lexile 600-670) Franny K Stein by Jim Benton (GR– N/ Lexile 740-840) The Life of Ty: Penguin Problems by Lauren Myracle Man Out at First by Matt (GR– M/ Lexile 540) Christopher (GR– M/ Lexile 590) Down Girl and Sit: Smarter Jake Drake, Bully Buster Than Squirrels by Lucy Nolan by Andrew Clements (GR– O/ (GR– L/ Lexile 380) Lexile 460) Junie B. Jones by Barbara Park Third Grade Pet by Judy Cox (GR– M/ Lexile 310-410) (GR– N/ Lexile 320) Amber Brown by Paula Danziger (GR– N,O/ Lexile 630- For children moving 760) up from Early Readers Mercy Watson Thinks Like a Pig by Kate DiCamillo (GR– K/ to Chapter Books! Lexile 380) Princess Posey by Stephanie Greene (GR– L/ Lexile 310-390) The Year of Billy Miller Pewaukee Public Library by Kevin Henkes (GR- P/ Lexile 620) 210 Main Street Pewaukee, WI 53072 Horrible Harry by Suzy Kline (262) 691-5670 (GR– L, M/ Lexile 470-580) [email protected] Gooney Bird Greene by Lois www.pewaukeelibrary.org Lowry (GR– N/ Lexile 590) Check us out on Facebook.com! *Guided Reading levels (GR) and Children’s Series Books Kylie Jean by Marci Peschke Lexile levels are given for each title. -

Read PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book)

Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) by Sandra Boynton, Download PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online, Read PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Full PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), All Ebook Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), PDF and EPUB Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), PDF ePub Mobi Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Reading PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Book PDF Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Read online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Sandra Boynton pdf, by Sandra Boynton Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), book pdf Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), by Sandra Boynton pdf Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Sandra Boynton epub Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), pdf Sandra Boynton Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), the book Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Sandra Boynton ebook Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) E-Books, Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Book, pdf Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) E-Books, Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online Download Best Book Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book), Read Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Book, Download Online Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) E-Books, Download Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online, Read Best Book Tickle Time! (A Boynton on Board Book) Online, Pdf Books Tickle Time! (A Boynton on -

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children for Children Through 3 Rd Grade Remember to Choose a Story That You Will Also Enjoy

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children rd for children through 3 grade Remember to choose a story that you will also enjoy The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken: Surrounded by villains of the first order, brave Bonnie and gentle cousin Sylvia conquer all obstacles in this Victorian melodrama. Poppy by Avi: Poppy the deer mouse urges her family to move next to a field of corn big enough to feed them all forever, but Mr. Ocax, a terrifying owl, has other ideas. The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks: A nine-year-old boy receives a plastic Indian, a cupboard, and a little key for his birthday and finds himself involved in adventure when the Indian comes to life in the cupboard and befriends him. Double Fudge by Judy Blume: His younger brother's obsession with money and the discovery of long-lost cousins Flora and Fauna provide many embarrassing moments for twelve-year-old Peter. The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary: A reckless young mouse named Ralph makes friends with a boy in room 215 of the Mountain View Inn and discovers the joys of motorcycling. How to Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell : Chronicles the adventures and misadventures of Hiccup Horrendous Haddock the Third as he tries to pass the important initiation test of his Viking clan, the Tribe of the Hairy Hooligans, by catching and training a dragon. Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher: Timid and small for her age, nine- year-old Elizabeth Ann discovers her own abilities and gains a new perception of the world around her when she goes to live with relatives on a farm in Vermont. -

101 Chapter Books to Read (Or Hear) Before You Grow Up

101 Chapter Books to Read (or Hear) Before You Grow Up feelslikehomeblog.com /2013/04/101-chapter-books-to-read-before-you-grow-up/ Tara Ziegmont It is worth noting that Grace loves a particular series of fairy books, but I hate them. Hate them. The text is dull and not well written. It’s the book form of candy, empty words without any redeeming intellectual value. There are probably books in your children’s lives that are the same way. Why not feed their little brains with good literature instead of junk books? Just like I limit the junk food in Grace’s belly, I limit the junk books in her brain. I’ll loosen up a little when she’s old enough to read her own books, but as long as I’m doing the reading, we are reading the good stuff. If I am going to take the time to read to Gracie (and I do, every single day), I want to hear her a book that is stimulating. I want a story that draws me in and makes me want to read just one more chapter! I want it to expand what Gracie knows – either in experiences or feelings or understanding of the world. I want a story with layers – something she may come back to again as an older kid or even an adult. There is no junk food here. (There’s also no junk food on my list of 101 Picture Books to Read or Hear Before You Grow Up. ) I’ve read almost every one of these books, either in my own childhood or recently. -

Open Access Monographs and Book Chapters: a Practical Guide for Publishers Open Access

Open Access Open Access Monographs and Book Chapters: A practical guide for publishers Open Access Background Contents Open access for monographs and book chapters is a Developing a publisher open access 3 relatively new area of publishing, and there are many policy and business model ways of approaching it. This document provides some guidance for publishers to consider when developing Signposting the monograph or 4 policies and processes for open access books. book chapter’s open access status The guide was written by the Wellcome Trust, Using third-party images 7 which extended its open access policy to include Wellcome Trust policy for open 8 monographs and book chapters in October 2013. Section 4 of this guide sets out Trust policy, but access monographs and book chapters otherwise the recommendations made here are Useful logos 9 intended as helpful suggestions for best practice rather than requirements. Annex A: Example copyright and 10 title pages with open access information We recognise that implementation around publishing monographs and book chapters open access is in flux, and we invite publishers to email Cecy Marden at [email protected] with any suggestions for further guidance that would be useful to include in this document. Endorsed by Open Access Developing a publisher open access policy and business model There are many different ways publishers can provide their authors with an open access option. Whichever route you choose, authors will want to know more about what your open access policy means and they will seek this information on your website. You may wish to include information on the following topics on an open access policy page: Licence Peer review Make it clear to authors what licences you offer, Some authors worry that open access publications are and provide them with information on the usage not subject to the same editorial processes as restrictions for each licence. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook #31428: Matter, Ether, and Motion

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Matter, Ether, and Motion, Rev. ed., enl., by Amos Emerson Dolbear This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Matter, Ether, and Motion, Rev. ed., enl. The Factors and Relations of Physical Science Author: Amos Emerson Dolbear Release Date: February 27, 2010 [EBook #31428] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MATTER, ETHER, AND MOTION *** Produced by Andrew D. Hwang, Peter Vachuska, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net transcriber’s note Minor typographical corrections and presentational changes have been made without comment. Illustrations may have been moved slightly relative to the surrounding text. Aside from clear misspellings, every effort has been made to preserve variations of spelling and hyphenation from the original. This PDF file is optimized for screen viewing, but may easily be recompiled for printing. Please see the preamble of the LATEX source file for instructions. By Profe&or A. E. Dol´ar MATTER, ETHER AND MOTION The Factors and Relations of Physical Science Enlarged Edition Cloth Illustrated $2.00 THE TELEPHONE With directions for making a Speaking Telephone Illustrated 50 cents THE ART OF PROJECTING A Manual of Experimentation in Physics, Chemistry, and Natural History, with the Porte Lumiere` and Magic Lantern New Edition Revised Illustrated $2.00 Lee and S˙«rd Publis˙rs Bo<on Matter,Ether, and Motion THE FACTORS AND RELATIONS OF PHYSICAL SCIENCE BY A. -

MEDIA PLANNER 2021 Publishersweekly.Com

Get In. Stand Out. MEDIA PLANNER 2021 PublishersWeekly.com CHILDREN’S STARRED REVIEWS ANNUAL 84,000,000 Web Ad Impressions Yearly 32,000,000 We Web Page Views Yearly 14,500,000 Wrote Opened Emails Yearly the 14,000,000 Unique Visitors Yearly BOOK 1,150,000 on Social Followers 1,000,000 Publishing Print Copies Publishers Weekly The Most Powerful Brand in the Business With nearly 150 years of history as a pioneer & leader, PW today is a global publication providing unparalleled reach to an ardent audience of industry professionals and devoted consumers around the globe. 9,000 Yearly Reviews 51 24/7 Breaking News Issues Influential Announcements Special School & Library Coverage 15 U.S. & International Trade Show Coverage Special Supplements Exclusive Author Interviews 68K Retail News & Bestsellers Lists Original Research & Industry-Wide Print & Digital Readers Surveys Audience 2%—Agents & Rights Professionals 1% 2%—Public Wholesalers/ Relations/Media Distributors 25% Librarians 44% Book Buyers & Booksellers 25% 1.15M Publishers Followers PW Show Daily The World Within Reach The consummate guide to all leading international trade shows, Show Dailies are unique opportunities to optimize your investment and stand out in a crowded marketplace. Distributed on-site throughout each venue, Show Dailies are the most potent tool for increasing visibility, driving traffic and boosting sales on the spot. And awareness extends far beyond a single event with supplements circulated to PW’s loyal print and digital readership of 68K, ensuring you never get lost in the crowd. Bologna MARCH 26, 2018 VISIT PW AT HALL 26 B38 Big, Bold Moves London Book Fair The Bologna Children’s Book Fair is updating its facilities and reaching out to new audiences, including, for the March 10–12 first time, booksellers BY ED NAWOTKA This year’s Bologna Children’s Book Fair has a different look for the 1,300 exhibitors and other industry members expected for the 2018 event. -

Text of Lectures on Physiology (1880) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TEXT OF LECTURES ON PHYSIOLOGY (1880) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles William Parsons | 84 pages | 22 May 2010 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781161962901 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Text of Lectures on Physiology (1880) PDF Book This energy rendered kinetic by oxy- dation, i,e, by slow combustion. Pancreatic digestion of futty compounds by a. Full text of " Syllabus of a Course of Lectures on Physiology Delivered at Guy's Hospital " See other formats Google This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Digestive cavity. Celij Lacta[n]tij Frimiani chritstiano[rum] eloquentissimi De opificio Dei, vel, Formatione hominis liber per vigintivnu[m] capita distributus, cu[m] eloque[n]tia, tum eruditione pr[ae]clarus. Functions unknown. Muscnlar fibres ; arteries, sinuses. Bew, and ant. Parker, Charles V. New York : Oxford Book Co. Typically you don't format your citations and bibliography by hand. Wagner, c , by Francis J. Hiatological differences. Non-sexual ovulation or parthenogenesis in insects and other invertebrata. XanlMn C. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei in Commission bei C. Travaux de la Socie te des naturalistes de St. Soluble in alkaline solutions ; imperfect proteiA reactions ; yields leucin and tyrosin. Urine of infant, child, adult. Un- changed chemically in its passage through the body. Serum-albumia , J and globulin ; absence of alkali-albumin in blood. Soe Tahk Cutter page images at HathiTrust A manual of experimental physiology for students of medicine. Diagram XV. Giulio Ceradini Louis, Mosby, , by William D. -

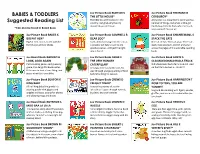

BABIES & TODDLERS Suggested Reading List

Juv Picture Book BURTON V Juv Picture Book FREEMAN D BABIES & TODDLERS THE LITTLE HOUSE* CORDUROY* The little house first stood in the A toy bear in a department store wants a Suggested Reading List country, but gradually the city number of things, but when a little girl moved closer and closer. finally buys him, he finds what he has al- *Can also be found in Board Book ways wanted most of all. Juv Picture Book BAKER K Juv Picture Book CAMPBELL R Juv Picture Book GHAHREMANI, S BIG FAT HEN* DEAR ZOO* STACK THE CATS Big Fat Hen counts to ten with her Each animal arriving from the zoo as One cat sleeps. Two cats play. Three cats friends and all their chicks. a possible pet fails to suit its pro- stack! Cats scamper, stretch and yawn spective owner, until just the right across the pages of this adorable counting one is found. book. Juv Board Book BARUZZI A Juv Picture Book CARLE E Juv Picture Book GOETZ S LOOK, LOOK AGAIN THE VERY HUNGRY OLD MACDONALD HAD A TRUCK Part counting game, part guessing CATERPILLAR* Old MacDonald had a farm E-I-E-I-O. And game, this delightful book invites A hungry little caterpillar eats his on that farm he had a...TRUCK?! little ones to look at one thing, and way through a large quantity of food guess what else it could be. before building his cocoon. Juv Picture Book BEATON K Juv Picture Book CREWS D Juv Picture Book HARRINGTON T KING BABY FREIGHT TRAIN* NOSE TO TOES, YOU ARE All hail King Baby! He greets his Traces the journey of a color- YUMMY! adoring public with giggles and ful train as it goes through tunnels, Sing and dance along with tigers, pandas, wiggles and coos, posing for photos by cities, and over trestles. -

Representations of Christopher Columbus Within Children's Literature

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Early Childhood, Elementary & Middle Level Faculty Research and Creative Activity Education July 2013 Examining Historical (Mis)Representations of Christopher Columbus within Children’s Literature John H. Bickford Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/eemedu_fac Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Bickford, John H., "Examining Historical (Mis)Representations of Christopher Columbus within Children’s Literature" (2013). Faculty Research and Creative Activity. 9. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/eemedu_fac/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Early Childhood, Elementary & Middle Level Education at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Examining Historical (Mis)Representations of Christopher Columbus within Children’s Literature J. H. Bickford III Eastern Illinois University Effective teaching, while supplemented by best practice methods and assessments, is rooted in accurate, age-appropriate, and engaging content. As a foundation for history content, elementary educators rely strongly on textbooks and children’s literature, both fiction and non- fiction. While many researchers have examined the historical accuracy of textbook content, few have rigorously scrutinized the historical accuracy of children’s literature. Those projects that carried out such examination were more descriptive than comprehensive due to significantly smaller data pools. I investigate how children’s non-fiction and fiction books depict and historicize a meaningful and frequently taught history topic: Christopher Columbus’s accomplishments and misdeeds. -

Mcgraw-Hill Connect and Create Version 2.0 Instructor Guide

Blackboard Learn Release 9.1 McGraw-Hill Connect and Create Version 2.0 Instructor Guide ©2011 Blackboard Inc. Proprietary and Confidential Publication Date: July 2011 Worldwide Headquarters International Headquarters Blackboard Inc. Blackboard International B.V. 650 Massachusetts Avenue N.W. Paleisstraat 1-5 Sixth Floor 1012 RB Amsterdam Washington, DC 20001-3796 The Netherlands 800-424-9299 toll free US & Canada +1-202-463-4860 telephone +31 (0) 20 788 2450 (NL) telephone +1-202-463-4863 facsimile +31 (0) 20 788 2451 (NL) facsimile www.blackboard.com www.blackboard.com Blackboard, the Blackboard logo, Blackboard Academic Suite, Blackboard Learning System, Blackboard Learning System ML, Blackboard Community System, Blackboard Transaction System, Building Blocks, and Bringing Education Online are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Blackboard Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Microsoft and Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Java is a registered trademark of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Macromedia, Authorware and Shockwave are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Macromedia, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Real Player and Real Audio Movie are trademarks of RealNetworks in the United States and/or other countries. Adobe and Acrobat Reader are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Macintosh and QuickTime are registered trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. WebEQ is a trademark of Design Science, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries.