Live to Tell Brad Kallenberg University of Dayton, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krt Madonna Knight Ridder/Tribune

FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE “Music” “Ray of Light” “Something to Remember” “Bedtime Stories” “Erotica” “The Immaculate “I’m Breathless” “Like a Prayer” “You Can Dance” (2000; Maverick) (1998; Maverick) (1995; Maverick) (1994; Maverick) (1992; Maverick) Collection”(1990; Sire) (1990; Sire) (1989; Sire) (1987; Sire) BY CHUCK MYERS Knight Ridder/Tribune Information Services hether a virgin, vamp or techno wrangler, Madon- na has mastered the public- image makeover. With a keen sense of what will sell, she reinvents herself Who’s That Girl? and transforms her music in Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone was ways that mystify critics and generate fan interest. born on Aug. 16, 1958, in Bay City, Mich. Madonna staked her claim to the public eye by challenging social norms. Her public persona has Oh Father evolved over the years, from campy vixen to full- Madonna’s father, Sylvio, was a design en- figured screen siren to platinum bombshell to gineer for Chrysler/General Dynamics. Her leather-clad femme fatale. Crucifixes, outerwear mother, Madonna, died of breast cancer in undies and erotic fetishes punctuated her act and 1963. Her father later married Joan Gustafson, riled critics. a woman who had worked as the Ciccone Part of Madonna’s secret to success has been family housekeeper. her ability to ride the music video train to stardom. The onetime self-professed “Boy Toy” burst onto I’ve Learned My Lesson Well the pop music scene with a string of successful Madonna was an honor roll student at music video hits on MTV during the 1980s. With Adams High School in Rochester, Mich. -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

SIR LANCELOT AUDITION PACKET I-4-8 Scene Four: Plague Village

SIR LANCELOT AUDITION PACKET I-4-8 Scene Four: Plague Village A Cart filled with dead bodies pushed by a man in rags enters upstage right. Robin, the Dead Collector, enters downstage right banging a triangle. MONKS: ( Offstage voices, pre recorded) Sacrosanctus Domine ROBIN: (live) Bring out your Dead! MONKS: Pecavi ignoviunt ROBIN: Bring out your dead! MONKS: Iuesus Christus Domine ROBIN: Bring out your dead! MONKS: Pax vobiscum venerunt Lance enters Stage Left dragging a small bubo covered man, apparently dead, by his feet. LANCE: Here's one. ROBIN: Nine pence. MAN: I'm not dead! ROBIN: What? LANCE: Nothing. Here's your nine pence. MAN: I'm not dead! ROBIN: Here, he says he's not dead! LANCE: Yes, he is. MAN: I'm not! ROBIN: He isn't. LANCE: Well, he will be soon, he's very ill. MAN: I'm getting better! LANCE: No, you're not, you'll be stone dead in a moment. ROBIN: I can't take him like that. It's against regulations. MAN: I don't want to go on the cart! LANCE: Oh, don't be such a baby. ROBIN: I can't take him... MAN: I feel fine! I-4-9 LANCE: Well, do us a favor... ROBIN: I can't. LANCE: Well, can you hang around a couple of minutes? He won't be long. ROBIN: Oh, Alright. Kevin. LANCE: Thanks, mate. The Carter picks up the sick man and carries him towards the cart. ROBIN: But make it quick, I got to get to Camelot by six. -

Madonna MP3 Collection - Madonna Part 2 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Madonna MP3 Collection - Madonna Part 2 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop Album: MP3 Collection - Madonna Part 2 Country: Russia Released: 2012 Style: House, Synth-pop, Ballad, Electro, RnB/Swing, Electro House MP3 version RAR size: 1708 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1392 mb WMA version RAR size: 1865 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 427 Other Formats: APE MP2 RA MP1 TTA VOX XM Tracklist Hide Credits Beautiful Stranger (Single) - 1999 1-1 Beautiful Stranger 4:24 1-2 Beautiful Stranger (Remix) 10:15 1-3 Beautiful Stranger (Mix) 4:04 Ray Of Light (Remix Album) - 1999 1-4 Ray Of Light (Ultra Violet Mix) 10:46 Drowned World (Substitut For Love (Bt And Sashas Remix) 1-5 9:28 Remix – Bt, Sasha Sky Fits Heaven (Sasha Remix) 1-6 7:22 Remix – Sasha Power Of Goodbay (Luke Slaters Filtered Mix) 1-7 6:09 Remix – Luke Slater 1-8 Candy Perfume Girl (Sasha Remix) 4:52 1-9 Frozen (Meltdown Mix - Long Version 8:09 1-10 Nothing Really Matters (Re-funk-k-mix) 4:23 Skin (Orbits Uv7 Remix) 1-11 8:00 Remix – Orbit* Frozen (Stereo Mcs Mix) 1-12 5:48 Remix – Stereo Mcs* 1-13 Bonus - What It Feels Like For A Girl (remix) 9:50 1-14 Bonus - Dont Tell Me (remix) 4:26 American Pie (Single) - 2000 1-15 American Pie (Album Version) 4:35 American Pie (Richard Humpty Vission Radio Mix) 1-16 4:30 Remix – Richard Humpty Vission* American Pie (Richard Humpty Vission Visits Madonna) 1-17 5:44 Remix – Richard Humpty Vission* Music - 2000 1-18 Music 3:45 1-19 Impressive Instant 3:38 1-20 Runaway Lover 4:47 1-21 I Deserve It 4:24 1-22 Amazing 3:43 -

Madonna's Postmodern Revolution

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2021, Vol. 11, No. 1, 26-32 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.01.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Rebel Madame: Madonna’s Postmodern Revolution Diego Santos Vieira de Jesus ESPM-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The aim is to examine Madonna’s revolution regarding gender, sexuality, politics, and religion with the focus on her songs, videos, and live performances. The main argument indicates that Madonna has used postmodern strategies of representation to challenge the foundational truths of sex and gender, promote gender deconstruction and sexual multiplicity, create political sites of resistance, question the Catholic dissociation between the physical and the divine, and bring visual and musical influences from multiple cultures and marginalized identities. Keywords: Madonna, postmodernism, pop culture, sex, gender, sexuality, politics, religion, spirituality Introduction Madonna is not only the world’s highest earning female entertainer, but a pop culture icon. Her career is based on an overall direction that incorporates vision, customer and industry insight, leveraging competences and weaknesses, consistent implementation, and a drive towards continuous renewal. She constructed herself often rewriting her past, organized her own cult borrowing from multiple subaltern subcultures, and targeted different audiences. As a postmodern icon, Madonna also reflects social contradictions and attitudes toward sexuality and religion and addresses the complexities of race and gender. Her use of multiple media—music, concert tours, films, and videos—shows how images and symbols associated with multiracial, LGBT, and feminist groups were inserted into the mainstream. She gave voice to political interventions in mass popular culture, although many critics argue that subaltern voices were co-opted to provide maximum profit. -

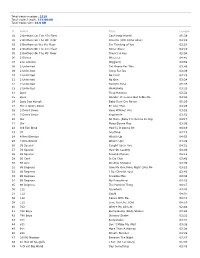

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Madonna E Seu Acervo Multiartístico: Os Fetichismos Visuais Na Obra Do Maior Mito

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação 41º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação – Joinville - SC – 2 a 8/09/2018 Madonna e seu Acervo Multiartístico: os fetichismos visuais na obra do maior mito 1 pop do século XX Rafael Nacif de Toledo PIZA2 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - UERJ Resumo O presente artigo pretende fazer uma retrospectiva da carreira da cantora Madonna, tendo como ponto de tensionamento os fetichismos visuais, conceito desenvolvido pelo italiano Massimo Canevacci em 2008. Nosso intuito é analisar o desenvolvimento cronológico da obra da cantora, relacionando suas iniciativas ao escopo teórico criado pelo sociólogo italiano, oferecendo pistas para decifrarmos os segredos de sua longevidade e do sucesso por trás de sua persona pública. Palavras-chave Madonna, cronologia, fetichismos visuais. Introdução Ser fã de Madonna é um privilégio e uma honra. Acompanhar a carreira de uma cantora, atriz, produtora, diretora de cinema, celebridade e personalidade é uma tarefa das mais prazerosas e dispendiosas. Montar uma coleção de objetos da Madonna pode custar alguns bons reais que poderiam ser investidos em outras coisas, como carros, roupas e outros itens de consumo. Mas deixando o lado mercantil de lado e focando na parte estética, o que Madonna nos apresenta é uma coleção de hits para as pistas de dança e baladas empacotados em formatos correspondentes às tecnologias do período, sempre com fotografias riquíssimas e figurinos ousados, tipologias inovadoras e designs de cair o queixo. Madonna e os fetichismos visuais de Canevacci Em 2008, Massimo Canevacci desenvolve “Fetichismos visuais: corpos erópticos e metrópole comunucacional” (Ateliê Editorial, 2008). -

Cryptic Match-Ups: Madonna Mindfood Wheel Words

Match-Ups: Madonna Cryptic Work out all the missing parts from these Madonna songs and find the Use the cryptic clues below to solve this crossword with a twist. words hidden in the box of letters. The letters left over will spell out a film Madonna starred in that featured one of the songs. I N S E C T S S W E P T U P N P A T E R S T B D E S Y F I T S U J A T E E L E A D E N C A S E H A O H C A E R P P Y E N I E L M S R V U G R G N T A K E L B A N Y M A D E T O M E A S U R E D I F L A I R E T A M A A M A O E W N L O L L E T I T U B Y R N M O T I P S T E R S H O I S T E H F S U E U T E N A E G E O U R A I L E D P A R T T I M E C S F F L Y S E R B T H E A N B C C H A K R E E I S N T O M H R T T F E A T H E R W E I G H T Y U Y K E T E E U E E E R H L R O O M R B Z O K K I L U I N M R Y A E R A S B R U N E I A C E A Y N N N L S A D E G A E N M E Y L C L R S A G R O O V E R U R H S T E P P E S M I L D E S T C S P E M I T D E B A P N ACROSS 28. -

Dying: a Spiritual Experience As Shown by Near Death Experiences and Deathbed Visions

Dying: a spiritual experience as shown by Near Death Experiences and Deathbed Visions Dr. Peter Fenwick Introduction In this talk I would like to suggest that dying is a process. First of all, I shall discuss those experiences which occur in the 24 hours or so before death - approaching death experiences - and secondly, the near death experience (NDE), looking at this as a model for death. It can be argued that the near death experience is not a good model for the death process itself, as everyone who has the experience lives to tell of it. However, there are reasons which I shall discuss, as to why this may be the best model that we have. Finally I want to look at some of the prospective NDE studies that have been done, to see whether we can find an explanatory framework for these, and what they can tell us about the spiritual experience of dying. Approaching death experiences Several groups of phenomena are reported in the 24 hours before death. The most often reported phenomena are ‘take-away’ visions - the so- called deathbed visions. These are visions seen by the person who is dying, in which figures are apparently seen who have the express purpose of collecting the dying person and taking them on a journey through physical death. A further group of reported phenomena are deathbed coincidences. These are coincidences, reported usually by family or friends of the person who is dying, in which they say that the dying person has visited them at the hour of death. Many relatives are reluctant to describe these phenomena, but nevertheless they are frequently reported. -

Track Title Artist It's Now Or Never Acoustic Moods Ensemble Stranger

Track Title Artist It's Now Or Never Acoustic Moods Ensemble Stranger on the Shore Acoustic Moods Ensemble Love Is a Losing Game Acoustic Moods Ensemble As Tears Go BY Acoustic Moods Ensemble Martha's Harbour Acoustic Moods Ensemble Guantanamera Acoustic Moods Ensemble Golden Brown Acoustic Moods Ensemble Because The Night Acoustic Moods Ensemble Make It Easy on Yourself Acoustic Moods Ensemble Walk on By Acoustic Moods Ensemble Something Stupid Acoustic Moods Ensemble Cavatina Acoustic Moods Ensemble Summer Breeze Acoustic Moods Ensemble Miss You Nights Acoustic Moods Ensemble Save the Last Dance For Me Acoustic Moods Ensemble Hotel California Acoustic Moods Ensemble Wonderful Tonight Acoustic Moods Ensemble Something Acoustic Moods Ensemble While My Guitar Gently Weeps Acoustic Moods Ensemble Lay Lady Lay Acoustic Moods Ensemble Fields Of Gold Acoustic Moods Ensemble The Wind Beneath My Wings Acoustic Moods Ensemble Wonderful Land Acoustic Moods Ensemble Time In a Bottle Acoustic Moods Ensemble And I Love Her Acoustic Moods Ensemble Yesterday Acoustic Moods Ensemble Here, There and Everywhere Acoustic Moods Ensemble Moon River Acoustic Moods Ensemble Nights In White Satin Acoustic Moods Ensemble Blue Moon Acoustic Moods Ensemble Wonderwall Acoustic Moods Ensemble La Isla Bonita Acoustic Moods Ensemble The Sound of Silence Acoustic Moods Ensemble Time After Time Acoustic Moods Ensemble I Don’t Want to Talk About IT Acoustic Moods Ensemble I'll Stand By You Acoustic Moods Ensemble In Sleep I Dream Of You Acoustic Moods Ensemble In The -

Madonna Lyrics Trivia Quiz

MADONNA LYRICS TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Some boys kiss me, some boys hug me. I think they're O.K... a. Like A Virgin b. Take a Bow c. Material Girl d. Live To Tell 2> Papa I know you're going to be upset 'cause I was always your little girl, but you should know by now I'm not a baby... a. Oh Father b. Papa Don't Preach c. Dress You Up d. Angel 3> I'm talking, I'm talking. I believe in the power of love. I'm singing, I'm singing... a. Justify My Love b. Frozen c. Don't Tell Me d. Rescue Me 4> Life is a mystery, everyone must stand alone. I hear you call my name and it feels like home... a. You'll See b. Borderline c. Keep It Together d. Like a Prayer 5> I see you on the street and you walk on by. You make me wanna hang my head down and cry... a. Keep It Together b. Open Your Heart c. Rain d. Deeper And Deeper 6> Look around everywhere you turn is heartache. It's everywhere that you go (look around) ... a. Holiday b. Don't Cry For Me Argentina c. This Used To Be My Playground d. Vogue 7> You must be my Lucky Star 'cause you shine on me wherever you are. I just think of you and I start to glow... a. Into the Groove b. Lucky Star c. Hanky Panky d. Hung Up 8> Surely whoever speaks to me in the right voice, him or her I shall follow.