Download Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stoke on Trent Pharmacies NHS Code Pharmacy Name Address Post Code Tel

Stoke On Trent Pharmacies NHS code Pharmacy Name Address Post Code Tel. No FRF34 Angelway Chemist 283 Waterloo Road Cobridge ST6 3HL 01782 280037 FJ346 ASDA Pharmacy Scotia Road Tunstall ST6 6AT 01782 820010 FKX58 Birchill & Watson 20 Knypersley Road Norton in the Moors ST6 8HX 01782 534678 FQK77 Blurton Pharmacy 7 Ingestre Square Blurton ST3 3JT 01782 314408 FRQ52 Boots the Chemists 39 Trentham Rd Longton ST3 4DF 01782 319758 FKV79 Boots the Chemists Unit 10 Alexandra Retail Park Scotia Road, Tunstall ST6 6BE 01782 838341 FDF31 Boots the Chemists 25 Bennett Precinct Longton ST3 2HX 01782 313819 FDH31 Boots the Chemists 3/5 Upper Market Square Hanley ST1 1PZ 01782 213271 FFV80 Boots the Chemists 41 Queen Street Burslem ST6 3EH 01782 837576 FK255 Boots the Chemists Bentilee Neighbourhood Centre Dawlish Drive, Bentilee ST2 0EU 01782 212667 FL883 Boots the Chemists Unit 5 Festival Park Hanley ST1 5SJ 01782 284125 Burslem Pharmacy Lucie Wedgwood Health Centre Chapel Lane, Burslem ST6 2AB 01782 814197 FWL56 Eaton Park Pharmacy 2 Southall Way Eaton Park ST2 9LT 01782 215599 FDF74 Grahams Pharmacy 99 Ford Green Road Smallthorne ST6 1NT 01782 834094 FTV00 Hartshill Pharmacy Hartshill Primary Care Centre Ashwell Road, Hartshill ST4 6AT 01782 616601 FRQ98 Heron Cross Pharmacy 2-4 Duke Street Heron Cross ST4 3BL 01782 319204 FFP79 Lloyds Pharmacy Cobridge Community H/ Centre Elder Road, Cobridge ST6 2JN 01782 212673 FM588 Lloyds Pharmacy 128 Werrington Road Bucknall ST2 9AJ 01782 219830 FA530 Lloyds Pharmacy Fenton Health Centre Glebedale Road, Fenton -

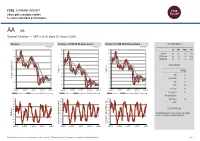

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance AA AA. General Retailers — GBP 0.25 at close 03 August 2020 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 0.7 140 140 1D WTD MTD YTD 130 130 Absolute 4.6 4.6 4.6 -57.0 0.6 Rel.Sector 2.4 2.4 2.4 -48.8 120 120 Rel.Market 2.5 2.5 2.5 -46.1 110 110 0.5 100 100 VALUATION 90 0.4 90 80 Trailing Relative Price Relative Relative Price Relative 80 70 0.3 PE 1.6 70 Absolute Price (local currency) (local Price Absolute 60 EV/EBITDA 8.0 60 50 0.2 PB -ve 50 40 PCF 0.7 0.1 40 30 Div Yield 2.6 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Price/Sales 0.1 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity - 100 90 90 Div Payout 4.6 90 80 80 ROE - 80 70 70 70 Index) Share Share Sector) Share - - 60 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 40 40 The principal activity of the Company is providing 40 RSI RSI (Absolute) service of consumer roadside assistance. -

Chatter~ Whitfield Mm Mining Museum

Chatter~ Whitfield mm Mining Museum By Car The colliery is approx 2 miles from Tunstall on the A527 to Biddulph and Congleton . • By Train From Stoke Station PMT (Red) buses 3/4/7/24/25/46 go to Hanley. From Congleton Station, Crosville (Green) buses 96/97/198 go to Biddulph . • By Bus From Hanley PMT route 6 to Biddulph. From Newcastle or Tunstall route 17 to Biddulph . • By Canal The colliery is approx 2 miles from the Caldan canal and 3 miles from the Trent and Mersey. Taxi service is available from your mooring. Tel: Stoke-on-Trent 534927 Chatterley Whitfield Mining Museum Trust Challerley Whitfield Colliery Tunstall . Stoke-on.Trent ST6 8UN Telephone: 0782 84221 Telephone: 0782 813337 (alter May 1979) Ch",Ueriey Whilhcld MmmQ MUSl'um Tru5t tf'Sf'rV"" Ih" nqhl to ••• tuse ",dml5$IOn lor Whdl ••vt .• purpos<'. Stoke-an-Trent is famous for its pottery, The Museum but the mining of coal has been an Saturday 26th May 1979 important industry in North Staffordshire Guided tours of the underground for many centuries. Coal could fire bottle workings begin on 26th May. ovens, drive steam engines and reduce Displays in the Holly Lane seam 700 feet iron are. It was an essential ingredient of below ground show the development of the Industrial Revolution. mining technology from hand working to modern machinery. North Staffordshire coal was collected from outcrops as early as the 13th century. Various pits existed at Whitfield • by 1800 but in 1900 Chatledey Whitfield Guided tours begin in the lamproom Colliery had grown to be the first in which offers an exhibition, museum shop Britain to win 1 million tons of coal a year. -

Industrial Heritage, Tourism and Old Industrial Buildings: Charting the Difficult Path from Redundancy to Heritage Attraction

RESEARCH Cutting Edge 1997 Industrial heritage, tourism and old industrial buildings: charting the difficult path from redundancy to heritage attraction Rick Ball, Staffordshire University ISBN 0-85406-864-3 INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE, TOURISM AND OLD INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS: CHARTING THE DIFFICULT PATH FROM REDUNDANCY TO HERITAGE ATTRACTION Dr. Rick Ball Division of Geography Staffordshire University Leek Road Stoke-on-Trent ST4 2DF UK Abstract This exploratory paper considers the processes, problems and constraints involved in the transition of old industrial buildings, often those prone to vacancy, into heritage and tourism- linked uses. It discusses the heritage-property nexus with regard to industrial buildings, and builds an empirical picture of such relationships in a specific local property arena. The discussion is partly based on research projects completed in a number of localities within the British West Midlands. In particular, it draws on work on the evaluation of European Commission Community Initiatives in the West Midlands that have targetted tourism development, as well as on EPSRC funded research focused on vacant industrial buildings in Stoke-on-Trent. As such, in scene-setting style, a structure is developed for the evaluation of heritage-property links with the emphasis on the small number of specific local projects that have at least partly sought to bring buildings back into use with some, perhaps extensive, degree of heritage activity in mind. 1. Heritage and the property domain - some introductory comments The background to this paper is the apparent reassertion of industrial heritage as a flavour of tourism in the late 1990s (Goodall, 1996), a process pursued with vigour in the quest for the renaissance of the urban industrial economy (see Ball and Stobart, 1996). -

City of Stoke Groups

City of Stoke Groups Growing older doesn’t mean you need to stop doing things you like to do, which help you keep fit and active. Our Exercise Groups promote better health for men and women aged 50+ and can help prevent falling by improving strength and balance. Low Mobility Classes Tuesday: Mary Church Centre, Bucknall, 10.30am - 12.30pm; Goldenhill Community Centre : 10.30 am - 12pm; Temple Street Methodist, Fenton, 10am - 12pm; Minton Community Centre, Hartshill, 12.30 - 1.30pm; Milton Methodist Church, 1.30 - 3.30pm. Wednesday: Longton Central Hall, 10am - 12pm; Holden Lane Primary, Sneyd Green, 7.15 - 8.15pm. Thursday: St Alban’s Comm. Centre, Blurton, ON HOLD; CCMA Cobridge, 10.30am - 12.30pm; Longton Central Hall, 10am - 12pm; Rowan Village, Meir, 2 - 4pm. Friday: Stoke Baptist Church,10.30am - 12.30pm. www.ageuk.org.uk/northstaffs Phone:01782 286 209 Registered Charity Number 1087774 Walking Groups ● Wednesday: City Walks, 1 mile, starts 2pm ● Friday: Step Out & Age Well, 5– 6 miles, meet at 9.45am. Walks led by accredited walk leaders. Ring the number below for further details. Age UK North Staffordshire… is a local, independent, registered charity working with and for older people in Stoke-on-Trent, Newcastle-under-Lyme and the Moorlands. We believe in a world where everyone can enjoy a fulfilling later life. We’re here to help, support and inspire people aged 50+, and their carers, to live well, safely and more easily. Our members tell us: “We have a really good time and feel much better for doing the exercises. -

Scsl Handbook 2021 22

1 2 STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY SENIOR LEAGUE Incorporating the Staffordshire County League (Founded in 1900) & the Midland League (Founded 1984) MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE PRESIDENT J.T. Phillips VICE PRESIDENTS M. Stokes Tel: 01543 878075 E-mail: [email protected] A Harrison Mobile 07789 632145 E-mail [email protected] CHAIRMAN R. Crawford 07761 514909(M) E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @scslchair VICE CHAIRMAN M. Stokes Tel: 01543 878075 E-mail: [email protected] LEAGUE SECRETARY C. Jackson E-mail: [email protected] 07761 514912(SecretarY ) 07763171456(M) TREASURER R. Bestwick Tel: 07967193546(M) Email: [email protected] REFEREE APPOINTMENTS SECRETARY R. Barlow Tel; 01782 513926, 07792412182 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] 3 FIXTURES TEAM R.Crawford R Bestwick D.Bilbie RESULTS SECRETARY D. Bilbie Mobile 07514786146 E-mail: [email protected] I.T. SUPPORT & DEVELOPMENT R. Bestwick, Tel: 07967193546(M) E mail: [email protected] DISCIPLINE SECRETARY S Matthews Tel ; 07761 514921 E-mail : [email protected] GROUNDS SECRETARY M. Sutton Tel: 07733098929(M) E-mail: [email protected] ELECTED OFFICERS & CLUB REPRESENTATIVES J.H. Powner J.Hilditch C.Humphries J.Greenwood J.Nealon WELFARE OFFICER & CLUB REPRESENTATIVE Mrs G Salt Tel: 07761 514919 E-mail: [email protected] LIFE MEMBER P. Savage M. Stokes 4 DISCIPLINE COMMITTEE S. Matthews P. Savage R. Crawford R. Barlow J.T. Phillips J.H. Powner M Stokes GROUNDS COMMITTEE M. Sutton J.T. Phillips M. Stokes P. Savage D. Vickers J. Cotton DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE FINANCE SUB R. Bestwick J.H. -

Kemball School Spring 2020 Newsletter

Kemball School Spring 2020 Newsletter Hello Everyone, Well I never thought that we would be ending the Spring term like this, with the whole country on lockdown, worried about catching a potentially deadly virus. These are indeed very scary times. This virus is very serious otherwise the Government would not be taking such extreme steps to protect people from catching and spreading it. With this in mind, as you know, we have made the decision to only open to certain pupils whose parents are either key workers or where, in conjunction with social care, we have identified that children will be at a greater risk by not coming into school. We made this decision for the following reasons: In order to provide a safe environment for our students, we need high ratios of well trained, medically competent, experienced staff who understand your children. With staff illness and their own vulnerabilities I can’t guarantee the same high student to teacher ratios that we need to safely meet the needs of the students. Concerns about the potential risk to the health of our children – if we take the government advice, by the very nature of our school, our children have underlying health conditions that make them vulnerable. Government guidance has identified having a learning need as being a vulnerable category. The Government have seemed to forgotten that having an EHCP won’t protect your child from catching the virus or bringing it back to their family. We are unable to keep a social distance in a school – our students are sociable and have no concept of personal space – we are unable to socially isolate Your child is having close 1:1 personal contact with our staff, particularly if they need physical management, feeding and personal care. -

Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan

Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council October 2020 Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Prepared for: Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council AECOM Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Table of Contents 1. Foreword ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 6 3. Contextual analysis ......................................................................................... 9 Kidsgrove Town Deal Investment Area ............................................................................................................. 10 Kidsgrove’s assets and strengths .................................................................................................................... 11 Challenges facing the town ............................................................................................................................. 15 Key opportunities for the town ......................................................................................................................... 19 4. Strategy ......................................................................................................... 24 Vision ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Summary of Outcomes of the Cycling Demonstration Towns and Cycling City and Towns Programmes

Summary of Outcomes of the Cycling Demonstration Towns and Cycling City and Towns Programmes Lynn Sloman, Andy Cope, Angela Kennedy, Fiona Crawford, Nick Cavill and John Parkin Report to the Department for Transport April 2017 The preferred citation for this paper is: Sloman L, Cope A, Kennedy A, Crawford F, Cavill N and Parkin J (2017) Summary of outcomes of the Cycling Demonstration Towns and Cycling City and Towns programmes This report was written by Transport for Quality of Life, based on analysis carried out by Sustrans Research and Monitoring Unit with Cavill Associates and University of the West of England, Bristol. www.transportforqualityoflife.com www.sustrans.org.uk www.cavill.net www.uwe.ac.uk Acknowledgements The authors are grateful for the extensive assistance of officers in the six Cycling Demonstration Towns and 12 Cycling City and Towns in providing monitoring data for this research. We are also grateful for additional support provided by Lisa Muller, Katie Pullen, George Macklon, Katie Thomson, James O’Hare, Richard Sanders, Alison Janes, Hannah Delaney, Laurence Bonner, Peter Stephenson, Charlotte Draycott and Jo Watson. Disclaimer Although this report was commissioned by the Department for Transport (DfT), the recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the DfT. While every effort has been made to ensure the information in this document is accurate, DfT does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of that information; and it cannot accept liability for any loss or damages of any kind resulting from reliance on the information or guidance this document contains. -

Inspection Report Goldenhill, St Joseph's

INSPECTION REPORT GOLDENHILL, ST JOSEPH’S CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL Goldenhill LEA area: Stoke-on-Trent Unique reference number: 124314 Headteacher: Mr J Tierney Reporting inspector: David Penney 23039 Dates of inspection: 9th – 12th July 2001 Inspection number: 213414 Full inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2001 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Primary School category: Voluntary Aided Age range of pupils: 3 – 11 years Gender of pupils: Mixed School address: Mobberley Road Goldenhill Stoke-on-Trent Staffordshire Postcode: ST6 5RN Telephone number: (01782) 235393 Fax number: (01782) 235394 Appropriate authority: The Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Mrs Christine Hulme Date of previous inspection: May 1999 Goldenhill, St Joseph’s RC Primary School - 1 INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Subject Aspect Team members responsibilities responsibilities 23039 David Penney Registered inspector Equal opportunities What sort of school is -

Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Stone | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Stoke on Trent and the Potteries from Stone Cruise this route from : Stone View the latest version of this pdf Stoke-on-Trent-and-the-Potteries-from-Stone-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 4.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 11.50 Total Distance : 18.00 Number of Locks : 24 Number of Tunnels : 0 Number of Aqueducts : 0 The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns, Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton that now make up the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. With an unrivalled heritage and very bright future, Stoke-on-Trent (affectionately known as The Potteries), is officially recognised as the World Capital of Ceramics. Visit award winning museums and visitor centres, see world renowned collections, go on a factory tour and meet the skilled workers or have a go yourself at creating your own masterpiece! Come and buy from the home of ceramics where quality products are designed and manufactured. Wedgwood, Portmeirion, Aynsley, Emma Bridgewater, Burleigh and Moorcroft are just a few of the leading brands you will find here. Search for a bargain in over 20 pottery factory shops in Stoke-on-Trent or it it's something other than pottery that you want, then why not visit intu Potteries? Cruising Notes Day 1 As you are on the outskirts of Stone, you may like to stay moored up and visit the town before leaving. -

N C C Newc Coun Counc Jo Castle Ncil a Cil St Oint C E-Und Nd S Tatem

Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement Joint Consultation Report July 2015 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Regulations Page 3 Consultation Page 3 How was the consultation on Page 3 the Draft Joint SCI undertaken and who was consulted Main issues raised in Page 7 consultation responses on Draft Joint SCI Main changes made to the Page 8 Draft Joint SCI Appendices Page 12 Appendix 1 Copy of Joint Page 12 Press Release Appendix 2 Summary list of Page 14 who was consulted on the Draft SCI Appendix 3 Draft SCI Page 31 Consultation Response Form Appendix 4 Table of Page 36 Representations, officer response and proposed changes 2 Introduction This Joint Consultation Report sets out how the consultation on the Draft Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) was undertaken, who was consulted, a summary of main issues raised in the consultation responses and a summary of how these issues have been considered. The SCI was adopted by Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council on the 15th July 2015 and by Stoke-on-Trent City Council on the 9th July 2015. Prior to adoption, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council respective committees and Cabinets have considered the documents. Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council’s Planning Committee considered a report on the consultation responses and suggested changes to the SCI on the 3RD June 2015 and recommended a grammatical change at paragraph 2.9 (replacing the word which with who) and this was reported to DMPG on the 9th June 2015.