The Mineral Industry of Botswana in 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bmo High Yield Bond Fund

Quarterly Portfolio Disclosure BMO HIGH YIELD BOND FUND Summary of Investment Portfolio • As at September 30, 2014 Q3 Top 25 Holdings Portfolio Allocation % of Net Asset Value Issuer % of Net Asset Value Corporate Bonds 86.1 Connacher Oil and Gas Limited, Series 144A, Money Market Investments 8.0 Secured, Notes, Callable, 8.500% Aug 1, 2019 2.1 Cash/Receivables/Payables 5.0 Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Other 0.9 Unsecured, Notes, 2.220% Mar 7, 2018 1.8 Government of Canada, Treasury Bills, 0.904% Oct 23, 2014 1.8 Total portfolio allocation 100.0 Pilgrim's Pride Corporation, Senior, Unsecured, Notes, Callable, 7.875% Dec 15, 2018 1.7 AGT Food & Ingedients, Inc., Senior, Secured, Top 25 Holdings Notes, Callable, 9.000% Feb 14, 2018 1.7 Issuer % of Net Asset Value Bombardier Inc., Senior, Unsecured, Debentures, 7.350% Dec 22, 2026 1.7 Cash/Receivables/Payables 5.0 Province of Ontario, Commercial Paper, 0.108% Oct 2, 2014 1.6 NRL Energy Investments Ltd., Senior, Unsecured, Armstrong Energy, Inc., Secured, Notes, Callable, Notes, Callable, 8.250% Apr 13, 2018 4.4 11.750% Dec 15, 2019 1.6 Millar Western Forest Products Ltd., Senior, Unsecured, Newalta Corporation, Series 2, Senior, Unsecured, Notes, Callable, 8.500% Apr 1, 2021 3.7 Notes, Callable, 7.750% Nov 14, 2019 1.6 NOVA Chemicals Corporation, Senior, Unsecured, Notes, Fairfax Financial Holdings Limited, Senior, Unsubordinated, Callable, 8.625% Nov 1, 2019 3.4 Unsecured, Notes, 7.375% Apr 15, 2018 1.5 Sherritt International Corporation, Senior, Unsecured, Data & Audio-Visual Enterprises -

Title – All Capital

TSX: IMG NYSE: IAG NEWS RELEASE IAMGOLD MEETS 2020 GUIDANCE: PRODUCING 653,000 OUNCES OF GOLD AND EXITING THE YEAR WITH $950 MILLION IN CASH ON HAND All 2020 figures are preliminary and unaudited and subject to final adjustment. All amounts are in US dollars, unless otherwise indicated. Toronto, Ontario, January 19, 2021 – IAMGOLD Corporation (“IAMGOLD” or the “Company”) announces preliminary operating results for the fourth quarter and year-end 2020, as well as guidance for 2021. Gordon Stothart, President and CEO of IAMGOLD, commented, “We achieved our target production and cost guidance in 2020 in the face of many and varied challenges throughout the year. Essakane had its strongest quarter at the end of the year, Rosebel production was up quarter-over-quarter and Westwood contributed by processing stockpile and Grand Duc open pit ore. Looking forward, IAMGOLD’s unique growth platform will enable our transformation to a lower cost producer of over one million ounces of annual production within the next two-and-a-half years. Our North American platform will see focused execution on the ongoing construction at the Côté Gold Project and we additionally expect to complete a maiden resource estimate at the nearby Gosselin discovery, with further advanced exploration at the Nelligan / Monster Lake district. We are developing our West African platform through ongoing de-risking at the Boto Gold Project in Senegal, and through the exploration and evaluation of nearby deposits and new discoveries, along with satellite targets anchored by the Rosebel mine at our South American platform.” Performance Highlights for 2020 Attributable gold production of 653,000 ounces, at the mid-point of guidance of 630,000 to 680,000 ounces; fourth quarter production of 169,000 ounces. -

LIST of LAW FIRMS NAME of FIRM ADDRESS TEL # FAX # Ajayi Legal

THE LAW SOCIETY OF BOTSWANA - LIST OF LAW FIRMS NAME OF FIRM ADDRESS TEL # FAX # Ajayi Legal Chambers P.O.Box 228, Sebele 3111321 Ajayi Legal Chambers P.O.Box 10220, Selebi Phikwe 2622441 2622442 Ajayi Legal Chambers P.O.Box 449, Letlhakane 2976784 2976785 Akheel Jinabhai & Associates P.O.Box 20575, Gaborone 3906636/3903906 3906642 Akoonyatse Law Firm P.O. Box 25058, Gaborone 3937360 3937350 Antonio & Partners Legal Practice P.O.Box HA 16 HAK, Maun 6864475 6864475 Armstrong Attorneys P.O.Box 1368, Gaborone 3953481 3952757 Badasu & Associates P.O.Box 80274, Gaborone 3700297 3700297 Banyatsi Mmekwa Attorneys P.O.Box 2278 ADD Poso House, Gaborone 3906450/2 3906449 Baoleki Attorneys P.O.Box 45111 Riverwalk, Gaborone 3924775 3924779 Bayford & Botha Attorneys P.O.Box 390, Lobatse 5301369 5301370 B. Maripe & Company P.O.Box 1425, Gaborone 3903258 3181719 B.K.Mmolawa Attorneys P.O.Box 30750, Francistown 2415944 2415943 Bayford & Associates P.O.Box 202283, Gaborone 3956877 3956886 Begane & Associates P.O. Box 60230, Gaborone 3191078 Benito Acolatse Attorneys P.O.Box 1157, Gaborone 3956454 3956447 Bernard Bolele Attorneys P.O.Box 47048, Gaborone 3959111 3951636 Biki & Associates P.O.Box AD 137ABE, Gaborone 3952559 Bogopa Manewe & Tobedza Attorneys P.O.Box 26465, Gaborone 3905466 3905451 Bonner Attorneys Bookbinder Business Law P/Bag 382, Gaborone 3912397 3912395 Briscoe Attorneys P.O.Box 402492, Gaborone 3953377 3904809 Britz Attorneys 3957524 3957062 Callender Attorneys P.O.Box 1354, Francistown 2441418 2446886 Charles Tlagae Attorneys P.O.Box -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

Appendix a IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (Previously Submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013

Summary of Consultation to Support the Côté Gold Project Closure Plan Côté Gold Project Appendix A IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (previously submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013 Stakeholder Consultation Plan (2013) TC180501 | October 2018 CÔTÉ GOLD PROJECT PROVINCIAL INDIVIDUAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROPOSED TERMS OF REFERENCE APPENDIX D PROPOSED STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION PLAN Submitted to: IAMGOLD Corporation 401 Bay Street, Suite 3200 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2Y4 Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, a Division of AMEC Americas Limited 160 Traders Blvd. East, Suite 110 Mississauga, Ontario L4Z 3K7 July 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Provincial EA and Consultation Plan Requirements ........................................... 1-1 1.3 Federal EA and Consultation Plan Requirements .............................................. 1-2 1.4 Responsibility for Plan Implementation .............................................................. 1-3 2.0 CONSULTATION APPROACH ..................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Stakeholder Identification .................................................................................. -

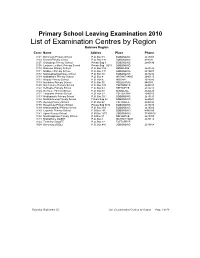

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

2017 SEAT Report Orapa, Letlhakane and Damtshaa Mines

SEAT 3 REPORT Debswana - Orapa, Letlhakane and Damtshaa Mine (OLDM) November 2017 1 2 FOREWORD rounded assessment of the socio-economic impacts of our operation – positive and negative - in our zone of influence. This is the second impact assessment of this nature being conducted, the first one having been carried out in 2014. The information in this socio-economic assessment report helped to improve our understanding of the local dynamics associated with the impact our operation’s that are real and perceived. It also provided us with invaluable insight into our stakeholders’ perspectives, expectations, concerns and suggestions. This report is a valuable tool to guide our thinking on community development and our management of the social impacts of OLDM’s future closure at the end of the life of mine. Furthermore, it provides a useful mechanism in mobilising local stakeholders to work with us towards successful mine closure. The report has also given valuable feedback on issues around mine expansion initiatives and access to resources like land and groundwater. More importantly, meaningful feedback has been provided around two critical areas: resettlement and options around town transformation. We recognise the complexity of a proper plan for future mine closure at the end of the life of mine. In the past, our plans for future mine closure mainly focused on environmental aspects, with community involvement often limited to cursory consultation processes. Today, in line with current trends, my team and I are convinced that community ownership of the post closure goals is the only sustainable means to propel communities to prosper when OLDM is no longer involved. -

Botswana Country Report-Annex-4 4Th Interim Techical Report

PROMOTING PARTNERSHIPS FOR CRIMEPREVENTION BETWEEN THE STATE AND PRIVATE SECURITY PROVIDERS IN BOTSWANA BY MPHO MOLOMO AND ZIBANI MAUNDENI Introduction Botswana stands out as the only African country to have sustained an unbroken record of liberal democracy and political stability since independence. The country has been dubbed the ‘African Miracle’ (Thumberg Hartland, 1978; Samatar, 1999). It is widely regarded as a success story arising from its exploitation and utilisation of natural resources, establishing a strong state, institutional and administrative capacity, prudent macro-economic stability and strong political leadership. These attributes, together with the careful blending of traditional and modern institutions have afforded Botswana a rare opportunity of political stability in the Africa region characterised by political and social strife. The expectation is that the economic growth will bring about development and security. However, a critical analysis of Botswana’s development trajectory indicates that the country’s prosperity has it attendant problems of poverty, unemployment, inequalities and crime. Historically crime prevention was a preserve of the state using state security agencies as the police, military, prisons and other state apparatus, such as, the courts and laws. However, since the late 1980s with the expanded definition of security from the narrow static conception to include human security, it has become apparent that state agencies alone cannot combat the rising levels of crime. The police in recognising that alone they cannot cope with the crime levels have been innovative and embarked on other models of public policing, such as, community policing as a public society partnership to combat crime. To further cater for the huge demand on policing, other actors, which are non-state actors; in particular private security firms have come in, especially in the urban market and occupy a special niche to provide a service to those who can afford to pay for it. -

BMO Equal Weight Global Gold Index ETF (ZGD) Summary of Investment Portfolio • As at September 30, 2019

QUARTERLY PORTFOLIO DISCLOSURE BMO Equal Weight Global Gold Index ETF (ZGD) Summary of Investment Portfolio • As at September 30, 2019 % of Net Asset % of Net Asset Portfolio Allocation Value Top 25 Holdings Value Canada ........................................................................................................ 60.1 Centerra Gold Inc. .............................................................. 3.6 United States .............................................................................................. 16.5 Gold Fields Limited, ADR ...................................................... 3.5 South Africa .................................................................................................. 9.7 OceanaGold Corporation ....................................................... 3.5 Australia ........................................................................................................ 3.5 Alacer Gold Corporation ....................................................... 3.5 Nicaragua ...................................................................................................... 3.4 Coeur Mining, Inc. ............................................................. 3.4 Cote D’Ivoire ................................................................................................. 3.3 Kirkland Lake Gold Ltd. ........................................................ 3.4 Brazil ............................................................................................................. 3.2 IAMGOLD Corporation -

Department of Road Transport and Safety Offices

DEPARTMENT OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND SAFETY OFFICES AND SERVICES MOLEPOLOLE • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 5920148 Fax: 5910620 P/Bag 52 Molepolole Next to Molepolole Police MOCHUDI • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate P/Bag 36 Mochudi Tel : 5777127 Fax : 5748542 White House GABORONE Headquarters BBS Mall Plot no 53796 Tshomarelo House (Botswana Savings Bank) 1st, 2nd &3rd Floor Corner Lekgarapa/Letswai Road •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Road safety (Public Education) Tel: 3688600/62 Fax : Fax: 3904067 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE VTS – MARUAPULA • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Vehicle Examination Tel: 3912674/2259 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst Near Roads Training & Roads Maintenance behind Maruapula Flats GABORONE II – FAIRGROUNDS • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination : Theory Tel: 3190214/3911540/3911994 Fax : P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE - OLD SUPPLIES • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Transport Permits • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 3905050 Fax :3932671 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone Plot 1221, Along Nkrumah Road, Near Botswana Power Corporation CHILDREN TRAFFIC SCHOOL •Road Safety Promotion for children only Tel: 3161851 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst RAMOTSWA •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Driver Examination (Theory & Practical -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Osler, 2020 Diversity Disclosure Practices Report

2020 Diversity Disclosure Practices Diversity and leadership at Canadian public companies By Andrew MacDougall, John Valley and Jennifer Jeffrey DIVERSITY DISCLOSURE PRACTICES Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt llp Table of contents Introduction 3 Developments in diversity: A wider focus 6 Our methodology 14 2019 full-year results 19 Mid-year results for 2020: Women on boards 23 Mid-year results for 2020: Women in executive officer positions 33 Diversity beyond gender: 2020 results for CBCA corporations 43 Who has achieved gender parity and how to increase diversity 49 Going above and beyond: Best company disclosure 64 The 2020 Diversity Disclosure Practices report provides general information only and does not constitute legal or other professional advice. Specific advice should be sought in connection with your circumstances. For more information, please contact Osler’s Corporate Governance group. 2 DIVERSITY DISCLOSURE PRACTICES Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt llp Introduction The diversity discussion blossomed this year, with continued, slow growth in the advancement of women accompanied by an expanded focus into other facets of diversity. This year new disclosure requirements under the Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA) broadened the range of corporations required to provide disclosure regarding women in leadership positions and added new requirements for disclosure regarding visible minorities, Aboriginal peoples and persons with disabilities. Our sixth annual comprehensive report on diversity disclosure practices now covers disclosure by TSX-listed companies and CBCA corporations subject to disclosure requirements. We continue to provide detailed disclosure on TSX-listed companies to provide year-over-year comparisons. However, we now include new chapters summarizing the results of our review of CBCA company disclosure.