Meeting the Great Masters – Part II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System

www.hbrreprints.org The Toyota story has been intensively researched and Decoding the DNA of painstakingly documented, yet what really happens inside the Toyota Production the company remains a mystery. Here’s new insight into the unspoken rules that System give Toyota its competitive edge. by Steven Spear and H. Kent Bowen Included with this full-text Harvard Business Review article: 1 Article Summary The Idea in Brief—the core idea The Idea in Practice—putting the idea to work 2 Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System 12 Further Reading A list of related materials, with annotations to guide further exploration of the article’s ideas and applications Reprint 99509 Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System The Idea in Brief The Idea in Practice Toyota’s renowned production system (TPS) TPS’s four rules: clude that their demand on the next ma- has long demonstrated the competitive ad- chine doesn’t match their expectations. All work is highly specified in its content, vantage of continuous process improve- They revisit the organization of their pro- sequence, timing, and outcome. ment. And companies in a wide range of duction line to determine why the machine Employees follow a well-defined sequence of industries—aerospace, metals processing, was not available, and redesign the flow steps for a particular job. This specificity en- consumer products—have tried to imitate path. ables people to see and address deviations TPS. Yet most fail. immediately—encouraging continual learn- Any improvement to processes, worker/ Why? Managers adopt TPS’s obvious prac- ing and improvement. -

Learning to See Waste Would Dramatically Affect This Ratio

CHAPTER3 WASTE 1.0 Why Studies have shown that about 70% of the activities performed in the construction industry are non-value add or waste. Learning to see waste would dramatically affect this ratio. Waste is anything that does not add value. Waste is all around, and learning to see waste makes that clear. 2.0 When The process to see waste should begin immediately and by any member of the team. Waste is all around, and learning to see waste makes this clear. CHAPTER 3: Waste 23 3.0 How Observations Ohno Circles 1st Run Studies/Videos Value Stream Maps Spaghetti Diagrams Constant Measurement 4.0 What There are seven common wastes. These come from the manufacturing world but can be applied to any process. They specifically come from the Toyota Production System (TPS). The Japanese term is Muda. There are several acronyms to remember what these wastes are but one of the more common one is TIMWOOD. (T)ransportation (I)ventory (M)otion (W)aiting (O)ver Processing (O)ver Production (D)efects. Transportation Unnecessary movement by people, equipment or material from process to process. This can include administrative work as well as physical activities. Inventory Product (raw materials, work-in-process or finished goods) quantities that go beyond supporting the immediate need. Motion Unnecessary movement of people or movement that does not add value. Waiting Time when work-in-process is waiting for the next step in production. 24 Transforming Design and Construction: A Framework for Change Look for and assess opportunities to increase value through waste reduction and elimination. -

SC2020: Toyota Production System & Supply Chain

SC2020: Toyota Production System & Supply Chain by Macharia Brown Bachelor of Science in Comparative Politics United States Military Academy, West Point 2003 Submitted to Zaragoza Logistics Center in Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Logistics and Supply Chain Management at the Zaragoza Logistics Center June 2005 © 2005 Brown, Macharia. All rights reserved The author hereby grant to M.I.T and ZLC permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Zaragoza Logistics Center May 10th, 2005 Certified by Prashant Yadav, PhD ZLC Thesis Supervisor Approved by Larry Lapide, PhD. Research Director, MIT-CTL Brown, TPS 0 Toyota Production System & Supply Chain by Macharia Brown Bachelor of Science in Comparitive Politics United States Military Academy, West Point 2003 Submitted to Zaragoza Logistics Center in Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Logistics and Supply Chain Management Abstract Over the past 50 years Toyota created and honed a production system that fostered its ascension in the automotive industry. Furthermore, the concepts that fuel Toyota’s production system extend beyond its manufacturing walls to the entire supply chain, creating a value chain where every link is profitable with an unwavering focus on teamwork, communication, efficient use of resources, elimination of waste, and continuous improvement. This report is a part of MIT’s Supply Chain 2020 (SC2020) research project focusing on Toyota’s production system and supply chain. The study begins by examining the automotive industry, evolution of top 5 automotive companies, and Toyota’s positioning against its main competitors. -

Mistakeproofing the Design of Construction Processes Using Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ)

www.cpwr.com • www.elcosh.org Mistakeproofing The Design of Construction Processes Using Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ) Iris D. Tommelein Sevilay Demirkesen University of California, Berkeley February 2018 8484 Georgia Avenue Suite 1000 Silver Spring, MD 20910 phone: 301.578.8500 fax: 301.578.8572 ©2018, CPWR-The Center for Construction Research and Training. All rights reserved. CPWR is the research and training arm of NABTU. Production of this document was supported by cooperative agreement OH 009762 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH. MISTAKEPROOFING THE DESIGN OF CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES USING INVENTIVE PROBLEM SOLVING (TRIZ) Iris D. Tommelein and Sevilay Demirkesen University of California, Berkeley February 2018 CPWR Small Study Final Report 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 1000 Silver Spring, MD 20910 www. cpwr.com • www.elcosh.org TEL: 301.578.8500 © 2018, CPWR – The Center for Construction Research and Training. CPWR, the research and training arm of the Building and Construction Trades Department, AFL-CIO, is uniquely situated to serve construction workers, contractors, practitioners, and the scientific community. This report was prepared by the authors noted. Funding for this research study was made possible by a cooperative agreement (U60 OH009762, CFDA #93.262) with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH or CPWR. i ABOUT THE PROJECT PRODUCTION SYSTEMS LABORATORY (P2SL) AT UC BERKELEY The Project Production Systems Laboratory (P2SL) at UC Berkeley is a research institute dedicated to developing and deploying knowledge and tools for project management. -

Isao Kato Article on Shigeo Shingo's Role at Toyota

Mr. Shigeo Shingo’s P-Course and Contribution to TPS By Isao Kato Retired Manager Training and Development Toyota Motor Corporation July 2006 © Isao Kato www.ArtofLean.com Mr. Shigeo Shingo taught an industrial engineering course at Toyota Motor Corporation and then decades later at Toyota affiliated companies starting in latter part of 1955. After 1960 and up until the mid 1980’s I organized his classes, edited the materials, as well as coordinated the majority of his training visits to the company. Before that time it was handled by one of my senior colleagues. Despite several myths and wide spread rumors the only course Mr. Shingo actually taught at Toyota was something called the P-course (the P stands for production) and he never was an instructor to Mr. Ohno or any other senior executives at that time. In fact they rarely met. However his association with Toyota Motor Corporation as an instructor did continue for close to 30 years and was highly beneficial to both parties although there were frustrations toward the end on both sides. As requested I will explain his actual role on the following pages for those interested in the actual history of events. There were actually four different versions of the P-course taught by Mr. Shingo that were held on average a couple of times per year during this period. There was also a longer version of the P-course that combined the different elements together that was taught every three or four years. I will outline the material below. The participants in the course were primarily young engineers in manufacturing. -

Lean Methodology and Its Derivates Usage for Production Systems in Modern Industry

Applied Engineering Letters Vol.2, No.4, 144-148 (2017) e-ISSN: 2466-4847 LEAN METHODOLOGY AND ITS DERIVATES USAGE FOR PRODUCTION SYSTEMS IN MODERN INDUSTRY Marko Miletić1, Ivan Miletić1 1Faculty of Engineering, University of Kragujevac, Serbia Abstract: ARTICLE HISTORY With lean methodology usage being the only way to stay competitive on Received 15.11.2017. nowadays market, it is important to implement it and spread it through the Accepted 07.12.2017. organization. Available 15.12.2017. In this paper, purpose of lean is explained, the most important definition and tools are given and differences between problem solving approaches are explained. KEYWORDS It can be concluded that problem solving approaches are in first look Lean Manufacturing, World Class Manufacturing, Toyota different, having also different number of steps, but they are adapted to the Production System, Basic Tools, company in which they are used and that they depend on the size, Continuous Improvement complexity and expected closing time of project. 1. INTRODUCTION which is initiated by management and bottom-up initiated by people on shop floor. The concept of lean methodology is nowadays Therefore, TPS is used in many industries and widely used in companies around the world in companies, adapted to its products and needs and order to maximise production by minimising loses now defined as common used methodologies such at the same time. Roots of integration of entire as: Lean [1], Lean Six Sigma [2], World Class production system done in flow was made by Manufacturing, Toyota Production System [3], Ford Henry Ford in 1913. However, true usage of lean Production System, Bosch Production System, etc… concept was started by Toyota owner Kiischiro Purpose of this paper is to show tools widely Toyoda and engineer Kaiichi Ohno after WWII, and used in these methodologies and present their finally summarized in 1980s rebranding their TPS main foundations. -

Lean Production and the Toyota Production System ± Or, the Case of the Forgotten Production Concepts Ian Hampson University of New South Wales

Lean Production and the Toyota Production System ± Or, the Case of the Forgotten Production Concepts Ian Hampson University of New South Wales Advocates and critics alike have accepted `lean' images of the Toyota production system. But certain production concepts that are integral to Toyota production system theory and practice actually impede `leanness'. The most important of these are the concepts of heijunka, or levelled (`balanced') production, and muri, or waste from overstressing machines and personnel. Actual Toyota production systems exist as a compromise between these concepts and the pursuit of leanness via kaizen. The compromise between these contrasting tendencies is in¯uenced by the ability of unions and other aspects of industrial relations regulation to counter practices such as short- notice overtime and `management by stress'. Introduction From the late 1980s, debate around work organization converged on the concept of `lean production' which was, according to its advocates, a `post-Fordist' system of work that is at once supremely ef®cient and yet `humane', even democratic (Kenney and Florida, 1988: 122; Adler, 1993; Mathews, 1991: 9, 21; 1988: 20, 23). How- ever, critical research found that, rather than being liberating, lean production can actually intensify work to the point where worker stress becomes a serious problem, because it generates constant improvements (kaizen) by applying stress and ®xing the breakdowns that result. It thus attracted such descriptions as `management by stress', `management by blame', `management by fear' (Parker and Slaughter, 1988; Sewell and Wilkinson, 1992; Dohse et al., 1985). Economic and Industrial Democracy & 1999 (SAGE, London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi), Vol. -

Toyota Production System Toyota Production System

SNS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AN AUTONOMOUS INSTITUTION Kurumbapalayam (Po), Coimbatore – 641 107 Accredited by NBA – AICTE and Accredited by NAAC – UGC with ‘A’ Grade Approved by AICTE, New Delhi & Affiliated to Anna University, Chennai TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM 1 www.a2zmba.com Vision Contribute to Indian industry and economy through technology transfer, human resource development and vehicles that meet global standards at competitive price. Contribute to the well-being and stability of team members. Contribute to the overall growth for our business associates and the automobile industry. 2 www.a2zmba.com Mission Our mission is to design, manufacture and market automobiles in India and overseas while maintaining the high quality that meets global Toyota quality standards, to offer superior value and excellent after-sales service. We are dedicated to providing the highest possible level of value to customers, team members, communities and investors in India. www.a2zmba.com 3 7 Principles of Toyota Production System Reduced setup time Small-lot production Employee Involvement and Empowerment Quality at the source Equipment maintenance Pull Production Supplier involvement www.a2zmba.com 4 Production System www.a2zmba.com 5 JUST-IN-TIME Produced according to what needed, when needed and how much needed. Strategy to improve return on investment by reducing inventory and associated cost. The process is driven by Kanban concept. www.a2zmba.com 6 KANBAN CONCEPT Meaning- Sign, Index Card It is the most important Japanese concept opted by Toyota. Kanban systems combined with unique scheduling tools, dramatically reduces inventory levels. Enhances supplier/customer relationships and improves the accuracy of manufacturing schedules. A signal is sent to produce and deliver a new shipment when material is consumed. -

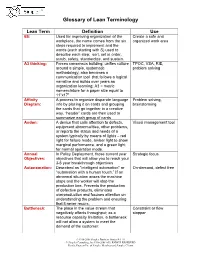

Glossary of Lean Terminology

Glossary of Lean Terminology Lean Term Definition Use 6S: Used for improving organization of the Create a safe and workplace, the name comes from the six organized work area steps required to implement and the words (each starting with S) used to describe each step: sort, set in order, scrub, safety, standardize, and sustain. A3 thinking: Forces consensus building; unifies culture TPOC, VSA, RIE, around a simple, systematic problem solving methodology; also becomes a communication tool that follows a logical narrative and builds over years as organization learning; A3 = metric nomenclature for a paper size equal to 11”x17” Affinity A process to organize disparate language Problem solving, Diagram: info by placing it on cards and grouping brainstorming the cards that go together in a creative way. “header” cards are then used to summarize each group of cards Andon: A device that calls attention to defects, Visual management tool equipment abnormalities, other problems, or reports the status and needs of a system typically by means of lights – red light for failure mode, amber light to show marginal performance, and a green light for normal operation mode. Annual In Policy Deployment, those current year Strategic focus Objectives: objectives that will allow you to reach your 3-5 year breakthrough objectives Autonomation: Described as "intelligent automation" or On-demand, defect free "automation with a human touch.” If an abnormal situation arises the machine stops and the worker will stop the production line. Prevents the production of defective products, eliminates overproduction and focuses attention on understanding the problem and ensuring that it never recurs. -

Lean Manufacturing and Reliability Concepts the Concepts Contained Within Lean Manufacturing Are Not Limited Merely to Production Systems

From the Reliability Professionals at Allied Reliability Group R LEAN MANUFACTURING & RELIABILITY CONCEPTS Inside: Key Principles of Lean Manufacturing 3 Types of Inspections for Mistake-Proofing A MUST-READ GUIDE FOR MAINTENANCE AND RELIABILITY LEADERS Allied Reliability Group © 2013 • 1 COPYRIGHT NOTICE Copyright 2013 Allied Reliability Group. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized use, sharing, reproduction or distribution of these materials by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise is strictly prohibited. No portion of these materials may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever, without the express written consent of the publisher. To obtain permission, please contact: Allied Reliability Group 4200 Faber Place Drive Charleston, SC 29405 Phone 843-414-5760 Fax 843-414-5779 [email protected] www.alliedreliabilitygroup.com 2nd Edition November 2013 2 • Allied Reliability Group © 2013 Lean Manufacturing TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................4 Part 1: 5S................................................................................................6 Part 2: Muda ......................................................................................... 11 Part 3: Key Principles of Lean Manufacturing ......................................16 Part 4: Poka-Yoke .................................................................................19 Kaizen...................................................................................................25 -

Page 1 of 8 Process Improvement Concepts and Terminology

Process Improvement Concepts and Terminology (A Guide to the Jargon) Disclaimer: Some statements/definitions are broad generalities intended as an initial introduction to Lean and Six Sigma concepts. (Not in alphabetical order) Methodologies and Related Concepts Lean – Process improvement methodology focused on reducing waste in a system. It is based heavily on the teachings of W. Edwards Deming and the Toyota Production System. The term Lean is derived from the idea that the approach reduces “wastes” that contribute to inefficient processes and poor outcomes. It does NOT refer to the idea that it is a way to cut staff as in the management adage: “lean and mean.” Mura – Japanese term that means “waste.” Key concept in Lean, which focuses on the reduction of “waste.” Muda – Japanese term that means “unevenness.” Workaround – Temporary fix to a system or process breakdown – a reaction to an immediate problem. In some cases, may not work well. Equivalent to “Duct tape on a split on a car radiator hose.” Not a permanent solution. Sometimes the result of procedures created without input from those involved in the process. A workaround does nothing to improve the situation in the future. PDCA/PDSA – Plan, Do, Check or Study, Act – A change process originally developed by Walter Shewhart (PDCA) and later revised by W. Edwards Deming (PDSA). It is sometimes referred to as the Deming wheel. It is intended to be used in multiple, successive cycles. © 2015 PCPI. All rights reserved. Page 1 of 8 Process Improvement Terminology (Jargon) Handout Error-proofing (“poka yoke” Japanese term) – the practice of making a process error proof, or make errors more apparent. -

A Study on Implementation of Poka– Yoke Technique in Improving the Operational Performance by Reducing the Rejection Rate in the Assembly Line

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 119 No. 17 2018, 2177-2191 ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.acadpubl.eu/hub/ Special Issue http://www.acadpubl.eu/hub/ A STUDY ON IMPLEMENTATION OF POKA– YOKE TECHNIQUE IN IMPROVING THE OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE BY REDUCING THE REJECTION RATE IN THE ASSEMBLY LINE 1Dr.Nanjundaraj Premanand, 2Dr. Kannan V, 3Sangeetha.P, 4Dr. S. Umamaheswari, 1Dean (Academics), D J Academy for Managerial Excellence, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, 2Professor, Department of Management, Kumaraguru College of Technology, Coimbatore, TamilNadu, India, 3Assistant Professor, D J Academy for Managerial Excellence, Coimbatore, TamilNadu, India, 4Associate Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Kumaraguru College of Technology, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT In today‟s competitive world any organization has to manufacture high quality, defect free products at optimum cost. The success of any industry depends on quality of their product. During actual manufacturing of any product, different operations are carried out by operators .The whole production depends on operator mentality and their interest in work which ultimately causes silly mistake or errors by the operator. Rejection of manufactured product cannot be ignored now a days in manufacturing industry due to worldwide competition. To avoid mistakes in assembly line, poka- yoke mechanism plays an important role in manufacturing industry. In the present work, an attempt is made to identify the areas of improvement in equipment. Kaizen and poka-yoke are implemented to enhance the overall performance to increase the productivity. Why-why method of root cause analysis is used to eliminate the causes.