The Knights Hospitaller of the English Langue 1460–1565

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

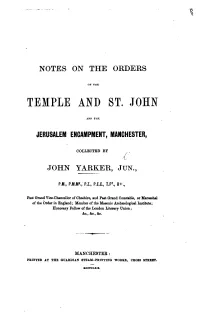

Notes on the Orders of the Temple and St. John and the Jerusalem

NOTES ON THE ORDERS OF THE TEMPLE AND ST, JOHN AND tit F. JERUSALEM ENEMPMENT, MANCHESTER, COLLECTED BY * * f JOHN YARKER, JUN., P.M., P.M.Mk, P.Z., P.E.C., T.P., R+, Past Grand Vice-Chancellor of Cheshire, and Past Grand Constable, or Mareschal of the Order in England; Member of the Masonic Archaeological Institute; Honorary Fellow of the London Literary Union; &c., &c., &c. MANCHESTER : PRINTED AT THE GUARDIAN STEAM-PRINTING WORKs, CROSS STREET. MDCCCLXIX. “To follow foolish precedents, and wink With both our eyes, is easier than to think.” - - - - - - TO FRATER ALBERT HUDSON ROYDS, GRAND COMMANDER OF LANCASHIRE, DEPUTY GRAND COMMANDER OF WORCESTERSHIRE, &c., &c., &c., THIS IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED. “It is, indeed, a blessing, when the virtues Of noble races are hereditary; And do derive themselves from th’ imitation Of virtuous ancestors.” 6 ramb #t a sters. PALESTINE, TEMPLE. ST. JOHN. Brother Brother 1 Hugh de Payens... ... ... 1118 J Raymond du Puis 1118 2 Lord Robert de Crayon ... 1136 2 Auger de Balben 1160 3. Everard de Barres - 1146 3 Arnaud de Comps 1163 4 Bernard de Tremelay ... 1151 4 Gilbert d’Assalit 1167 5 Bertrand de Blanquefort ... 1153 5 Gastus ... ... ... 1168 6 Philip de Naplous ... 1167 6 Aubert of Syria 1170 7 Odo de St. Amand 1170 7 Roger de Moulin... 1177 8 Arnold de Torrage ... ... 1179 8 Garnier de Naplous 1187 9 Gerard de Riderfort ... 1185 9 Ermengard Daps... 1187 10 Walter ... ... ... ... 1191 | 10 Godfrey de Duisson ... 1.191 11 Robert de Sable, or Sabboil. 1191 | 11 Alphonso de Portugal... ... 1202 12 Gilbert Horal, or Erail .. -

John HALES, Descended of a Younger Branch of the Family Of

120 DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE FAMILY OF HALES, OF COVENTRY, AND THE FOUNDATION OF 'l'HE FREE SCHOOL, JoHN HALES, descended of a younger branch of the family of Hales of W oodchurch in Kent, 8 is a name deserving of the commemoration of posterity, as the Founder of the Gram• mar School of Coventry. He was himself a learned man, and an author, and some account of him and his works will be found in the Athenee Oxonienses of Anthony Wood. He was Clerk of the Hanaper to Henry VIII.; and " having," as Dugdale says, " accumulated a great estate in monastery and chantry lands," he established a Free School in the church of the White Friars of Coventry. He died in 1572, and was buried in the church of St. Peter le Poor, in Broad Street, London. b 'fhe estates of John Hales, Esq, descended principally to his nephew John, son of his elder brother Christopher, c by Mary, daughter of Thomas Lucy, Esq. of Charlecote, Warwickshire. This John built a mansion at Keresley, near Coventry, where he resided. In 1586, he married Frideswede, daughter of Wil• liam Faunt, of Foston, in Leicestershire, Esq. and widow of Robert Cotton, Esq. She was buried in a vault on the north • There were three Baronetcies in this family, all of which have become extinct ,tithin the present generation: Hales of Woodchurch in Kent, created 1611, ex• tinct with the sixth Baronet in 1829; Hales of Beaksboume in Kent, created in 1660, extinct with the fifth Baronet in 1824; and Hales of Coventry, also created in 1660, extinct with the eighth Baronet in or shortly before 1812, See Court• hope's Extinct Baronetage, 1835, pp, 92, 93: Burke's Extinct Baronetages, 1841, pp, 232, 235, 236 : and fuller accounts in Wotton's English Baronetage, 1741, Toi, I. -

1 Richard Cloudesley's Modern Fame Rests on the Charity Bearing His

Richard Cloudesley’s modern fame rests on the charity bearing his name, and perhaps some people living in Islington associate him correctly with Cloudesley Place, Road and Square. With the loss of so many official records from the Tudor period and in the absence of any private papers, Richard Cloudesley must remain a somewhat shadowy figure, but sufficient survives to enable us to reconstruct his career, and to gain some insight into his life. In I509, shortly after the accession of Henry Vlll, he described himself, somewhat loosely, as a ‘husbandman, yeoman or gentleman’ living in Islington when he took the precaution of suing out a general pardon1. Such pardons were a matter of course for men of some substance and position, which was precisely what Cloudesley was. As a ‘husbandman, yeoman or gentleman’, he belonged to a class which with an income of at least ₤40 a year qualified to serve as a juror in a variety of proceedings, to hold office in shire administration, to pay taxes and to vote in parliamentary elections. (At the turn of the sixteenth century £40 freeholders in Middlesex numbered some I200.) In other words, he belonged to the class upon which the routine running of the kingdom fell. What has come to light about him reveals him to have been an active member of his class, a prominent figure in Islington and its locality. Cloudesley was Islington born and bred. Although he himself was to live somewhere not far from the parish church, to which it was linked by a ‘causeway’ (a raised road), his parents had lived at the north end of the town, more conveniently situated near the chapel called the Hermitage where they worshipped, and where masses were said for their souls after their deaths. -

Local Government and Society in Early Modern England: Hertfordshire and Essex, C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Local government and society in early modern England: Hertfordshire and Essex, C. 1590-- 1630 Jeffery R. Hankins Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hankins, Jeffery R., "Local government and society in early modern England: Hertfordshire and Essex, C. 1590-- 1630" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 336. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/336 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND: HERTFORDSHIRE AND ESSEX, C. 1590--1630 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of History By Jeffery R. Hankins B.A., University of Texas at Austin, 1975 M.A., Southwest Texas State University, 1998 December 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Victor Stater for his guidance in this dissertation. Dr. Stater has always helped me to keep the larger picture in mind, which is invaluable when conducting a local government study such as this. He has also impressed upon me the importance of bringing out individual stories in history; this has contributed greatly to the interest and relevance of this study. -

Notes on the Docker Family of Westmorland by George Lissant London, 1917

Notes on the Docker Family Of Westmorland By George Lissant London, 1917 PREFACE These notes were made at the suggestion of a kinswoman who wished to know something of her Docker ancestry and connections. I had no intention of finding “blue blood” or “money in it”. Certainly, I have found affluence in some cases where the character and enterprise of the individual won it and which, quite justly, has not been diverted from lawful descendants. But aristocratic origin for the family is not forthcoming. However, better than this, I can record an ancient yeoman lineage notable for its sterling worth and exceptional culture. Westmorland has been particularly favoured in its educational endowments and this accounts for the fact that so many “Statesmen’s” sons rose to distinction in the professions and in public life, among them Dockers or their kinsfolk. Is this not sufficient? As to the story here set out I must explain that it is a purely amateur effort and limited by the means and time at my disposal. Hence, indulgence is claimed for its imperfections. The pedigree here given will at least serve as the basis for a fuller story by those disposed to attempt it, an, it is hoped, may be the means of maintaining the unity of the family by making distant branches, who hitherto were strangers to each other, fully to realize that they are of the same kindred. For the story before 1800 I am entirely responsible; for later information I am in some degree indebted to members of the family, and I take this opportunity of thanking them for their assistance and for their courtesy and patience under importunate questioning. -

Sanctuary Seekers in England, 1380-1557 (Ordered by Date)

(London: G. Sanctuary Seekers in England, 1380-1557 (ordered by date) Shannon McSheffrey Professor of History, Concordia University The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Mediaeval England © Shannon McSheffrey, 2017 archive.org Illustration by Ralph Hedley from J. Charles Cox, Allen and Sons, 1911), p. 108. 30/05/17 Sanctuary Seekers in England, c. 1380-1550, in Date Order Below are presented, in tabular form, all the instances of sanctuary-seeking in deal of evidence except for the name (e.g. ID #1262). In order to place those England that I have uncovered for the period 1380-1557, more than 1800 seekers seekers chronologically over the century and a half I was considering, in the altogether. It is a companion to my book, Seeking Sanctuary: Crime, Mercy, and absence of exact dates I sometimes assigned a reasonable year to a seeker (always Politics in English Courts, 1400-1550 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). As I noted in the summary section). As definitions of specific felonies were somewhat have continued to add to the data since that book went to press, the charts here elastic in this era, I have not sought to distinguish between different kinds of may be slightly different from those in the book. asportation offences (theft, robbery, burglary), and have noted in the summary different forms of homicide only as they were indicated in the indictment. Details Seeking Sanctuary explores a curious aspect of premodern English law: the right of on the offences are noted in the summaries of the cases; there is repetition in the felons to shelter in a church or ecclesiastical precinct, remaining safe from arrest cases where several perpetrators were named in a single document so that and trial in the king's courts. -

Sanctuary Seekers in England, 1380-1557 (Ordered by Surname)

(London: G. Sanctuary Seekers in England, 1380-1557 (ordered by surname) Shannon McSheffrey Professor of History, Concordia University The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Mediaeval England © Shannon McSheffrey, 2017 archive.org Illustration by Ralph Hedley from J. Charles Cox, Allen and Sons, 1911), p. 108. 30/05/17 Sanctuary Seekers in England, c. 1380-1550, ordered by seekers' names Below are presented, in tabular form, all the instances of sanctuary-seeking in of evidence except for the name (e.g. ID #1262). In order to place those seekers England that I have uncovered for the period 1380-1557, more than 1800 seekers chronologically over the century and a half I was considering, in the absence of altogether. It is a companion to my book, Seeking Sanctuary: Crime, Mercy, and exact dates I sometimes assigned a reasonable year to a seeker (always noted in Politics in English Courts, 1400-1550 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). As I the summary section). As definitions of specific felonies were somewhat elastic in have continued to add to the data since that book went to press, the charts here this era, I have not sought to distinguish between different kinds of asportation may be slightly different from those in the book. offences (theft, robbery, burglary), and have noted in the summary different forms of homicide only as they were indicated in the indictment. Details on the offences Seeking Sanctuary explores a curious aspect of premodern English law: the right of are noted in the summaries of the cases; there is repetition in the cases where felons to shelter in a church or ecclesiastical precinct, remaining safe from arrest several perpetrators were named in a single document so that complete records and trial in the king's courts. -

The King, the Cardinal-Legate and the Field of Cloth of Gold

2017 IV The King, the Cardinal-Legate and the Field of Cloth of Gold Glenn Richardson Article: The King, the Cardinal-Legate, and the Field of Cloth of Gold The King, the Cardinal-Legate, and the Field of Cloth of Gold Glenn Richardson Abstract: The Field of Cloth of Gold was a meeting in June 1520 between King Francis I of France and King Henry VIII of England. They met to affirm a treaty of peace and alliance between them, which was itself the centre of an international peace between most European princes. The presiding intelligence over the meeting was Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, simultaneously the Lord Chancellor of England and Pope Leo X’s legate a latere in England.1 This article looks at the context of that event from Wolsey’s perspective, examining how the Universal Peace of 1518 was used in his own ambitions as well as those of Henry VIII. It shows how Wolsey strove to use the international situation at the time to obtain legatine authority, principally to advantage his own king, and himself, rather than the pope whose legate he was, and in whose name he ostensibly acted. Keywords: Field of Cloth of Gold; legate a latere; Leo X; Thomas Wolsey; Charles V; Francis I; Henry VIII; Universal Peace; Clement VII; Adrian VI Cardinal-Legate he Field of Cloth of Gold had its inception in plans for international Christian peace first laid out by Pope Leo X when, on 6 March 1518, he proclaimed a five- year international truce among European sovereigns and states, as the necessary T prelude to a crusade to retake Istanbul from the Ottomans. -

Hugo, T, Mynchin Buckland Priory and Preceptory, Part II, Vol 10

PROCEEDINGS OP THE SOMERSETSHIRE ARCHEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, 1860, PART II. PAPERS, ETC. Bijntljm fnicklonlt ^rinrij nnk BY THE REV. THOMAS HUGO, M.A., F.S.A., E.R.S.L., ETC., HON. MEMBER. lONG the many delightful roads by which a traveller in the west may reach on all sides the fair town of Taunton, he will find few, if any, more agreeable than that which runs from Borough Bridge to the village of Durston, and then, with West Monkton at a short distance on the right and Creech S. Michael on the left, leads him through our favorite Bathpool, and by its picturesque mills, either along the ancient highway, commonly called Old Bathpool Lane, under Creechbury Hill, or by the windings of the Tone and the Priory Fields, to the busy streets and the consequent termination of his journey. He will not have advanced far on the route that I have here laid down, when the matchless vale of Taunton Dean, with its churches and steeples, its mansions and parks, its corn-fields and groves, and its noble framework of Neroche and Blackdown, above the sunny shoulders of Thornfalcon and Stoke, of Orchard VOL. X., 1860, PART II. A 2 PAPERS, ETC. and Pickeridge, opens wide before him, and he only relin- quishes the charms of the more distant prospect for the shady lanes, the luxuriant vegetation, the tall trees, the lovely river, and the snugly sheltered homesteads, of which his descent into the lowlands soon gratifies him with the closer view. After passing the hamlet of West Ling, and when he is within half a mile from Durston, he may observe in a meadow on his right hand some curious inequalities of the surface, contracting and expanding with that certain definiteness and regularity of outline which assures him of the presence of design on the part of the constructors, though it is more than likely that he may be unable to offer an explanation of the intention which not the less certainly actuated them in their labours. -

The Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem

~_r tflA/faL^ THE ORDER OF THE HOSPITAL OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM ST. JOHN'S GATE, FROM THE SOUTH, 1902 THE ORDE OF THE HOSPITAL OF St. John of Jerusalem BEING A HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH HOSPITALLERS OF ST. JOHN, THEIR RISE AND PROGRESS BY K, W. K. R. BEDFORD, M.A. Oxon. GENEALOGIST OF THE ORDER AND RICHARD HOLBECHE, Lt.-Col. LIBRARIAN OF THE ORDER LONDON: F. E. ROBINSON AND CO. 20, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, BLOOMSBURY 1902 S1.4 1 1. 3. 5*5 CHISWICK PRKSS : CHARLES Wlll'l TINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. PREFACE Editor desires to say a few, a very few, THEwords of preface by way of explanation of the origin and object of the present volume. Its inception commenced with a successful illus- trated lecture delivered by Major Yate at the United Service Institution, which he wished the Order to reprint for general publication. The Council thought it expedient that the narrative should be somewhat enlarged, and circumstances preventing Major Yate from superintending the work, it was intrusted by the Council to the Genealogist, who again found it somewhat beyond his powers, and had to apply to the Librarian for assistance, especially in the later and more immediately interesting portions of the narrative, though retaining the general supervision of the whole. The Editor would adopt as his own the apology of " the author of the books of Maccabees : If I have done well, and as is fitting the story, it is that which I desired but if ; slenderly and meanly, it is that which I could attain unto." Mr. -

\\P450\D\My Documents\St. John Toronto Area\Knowledge\Course

The Order of St. John - Knowledge Of The Order THE GRAND PRIORY IN THE BRITISH REALM OF THE MOST VENERABLE ORDER OF THE HOSPITAL OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM Student Workbook Category “A” Proficiency Contributors Originally complied by W.D. Doug Kirkwood - 1996 2002 Edition complied by Samantha E. C. Smith 1 of 31 The Order of St. John - Knowledge Of The Order Introduction Proficiency Requirements. Minimum age 14 years. Textbooks - The Order of St. John (A Short History) The White Cross In Canada 1883-1983 Assignment Question Sheets must be completed and turned into the Course Instructor for review. Progress Tests will be administered by the Instructor. 70% average is expected for assignments and tests 70% is required to pass Final Examination 1. EARLY ORIGINS; THE ORDER IN THE HOLY LAND Handouts 1-1 Outline Map of the Mediterranean Area 1-2 Map and Dates of the Order in the Holy Land Assignment Section 1 Question Sheet Test #1 2. THE ORDER IN CYPRUS AND RHODES Handouts 2-1 Map and Dates of the Order; Cyprus, Rhodes, Malta 2-2 Chart of the Order of Government in Rhodes, Malta Assignment Section 2 Question Sheet 3. THE ORDER IN MALTA Assignment Section 3 Question Sheet Test #2 4. THE ORDER IN ENGLAND Handouts 4-1 Pictures and Dates of the Order in England (early) 4-2 Pictures and Dates of the Order in England (later) 4-3 The Order and Foundations; Objects of the Order Assignments Section 4 Question sheet Test #3 Important dates Test #4 Important names 5. THE OPHTHALMIC HOSPITAL Assignment Section 5 Question Sheet 6. -

The Chronicle of Calais in the Reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII to The

THE CHRONICLE OF CALAIS, IN THE REIGNS OF HENRY VII. AND HENRY VIII. TO THE YEAR 1540. EDITED FROM MSS. IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM, BY JOHN GOUGH NICHOLS, F.S.A. LONDON: PRINTED FOR THE CAMDEN SOCIETY, J. BY B. NICHOLS AND SON, 25, PARLIAMENT STREET. M.DCCC.XL.VI. en [xo. xxxv.j COUNCIL OF THE C AMD EN SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR 1845. President, THE RIGHT HON. LORD BRAYBROOKE, F.S.A. THOMAS AMYOT, ESQ. F.R.S., Treas. S.A. Director. JOHN PAYNE COLLIER, ESQ. F.S.A. Treasurer. C. PURTON COOPER, ESQ. Q.C., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.S.A. BOLTON CORNEY, ESQ. T. CROFTON CROKER, ESQ. F.S.A., M.R.I. A. SIR HENRY ELLIS, K.H., F.R.S., Sec. S.A. THE REV. JOSEPH HUNTER, F.S.A. PETER LEVESQUE, ESQ. F.S.A. SIR FREDERIC MADDEN, K.H., F.R.S., F.S.A. THOMAS JOSEPH PETT1GREW, ESQ. F.R.S., F.S.A. THOMAS STAPLETON, ESQ. F.S.A. WILLIAM J. THOMS, ESQ. F.S.A., Secretary. SIR HARRY VERNEY, BART. ALBERT WAY, ESQ. M.A., DIR. S.A. THOMAS WRIGHT, ESQ. M.A., F.S.A. The COUNCIL of the CAMDEN SOCIETY desire it to be under- stood that they are not answerable for any opinions or observa- tions that in the the Editors may appear Society's publications ; of the several Works being alone responsible for the same. CONTENTS. PAGE Preface ....... ix Biographical notices of Richard Turpyn the chronicler, and his son Richard Turpyn the herald, victualler of Calais .