Non-Uniform Memory Affinity Strategy in Multi-Threaded Sparse Matrix Computations" (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers

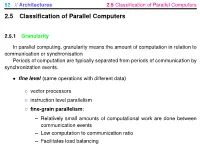

52 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.1 Granularity In parallel computing, granularity means the amount of computation in relation to communication or synchronisation Periods of computation are typically separated from periods of communication by synchronization events. • fine level (same operations with different data) ◦ vector processors ◦ instruction level parallelism ◦ fine-grain parallelism: – Relatively small amounts of computational work are done between communication events – Low computation to communication ratio – Facilitates load balancing 53 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers – Implies high communication overhead and less opportunity for per- formance enhancement – If granularity is too fine it is possible that the overhead required for communications and synchronization between tasks takes longer than the computation. • operation level (different operations simultaneously) • problem level (independent subtasks) ◦ coarse-grain parallelism: – Relatively large amounts of computational work are done between communication/synchronization events – High computation to communication ratio – Implies more opportunity for performance increase – Harder to load balance efficiently 54 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.2 Hardware: Pipelining (was used in supercomputers, e.g. Cray-1) In N elements in pipeline and for 8 element L clock cycles =) for calculation it would take L + N cycles; without pipeline L ∗ N cycles Example of good code for pipelineing: §doi =1 ,k ¤ z ( i ) =x ( i ) +y ( i ) end do ¦ 55 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers Vector processors, fast vector operations (operations on arrays). Previous example good also for vector processor (vector addition) , but, e.g. recursion – hard to optimise for vector processors Example: IntelMMX – simple vector processor. -

Chapter 5 Multiprocessors and Thread-Level Parallelism

Computer Architecture A Quantitative Approach, Fifth Edition Chapter 5 Multiprocessors and Thread-Level Parallelism Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Centralized SMA – shared memory architecture 3. Performance of SMA 4. DMA – distributed memory architecture 5. Synchronization 6. Models of Consistency Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 2 1. Introduction. Why multiprocessors? Need for more computing power Data intensive applications Utility computing requires powerful processors Several ways to increase processor performance Increased clock rate limited ability Architectural ILP, CPI – increasingly more difficult Multi-processor, multi-core systems more feasible based on current technologies Advantages of multiprocessors and multi-core Replication rather than unique design. Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 3 Introduction Multiprocessor types Symmetric multiprocessors (SMP) Share single memory with uniform memory access/latency (UMA) Small number of cores Distributed shared memory (DSM) Memory distributed among processors. Non-uniform memory access/latency (NUMA) Processors connected via direct (switched) and non-direct (multi- hop) interconnection networks Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Important ideas Technology drives the solutions. Multi-cores have altered the game!! Thread-level parallelism (TLP) vs ILP. Computing and communication deeply intertwined. Write serialization exploits broadcast communication -

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4 Manfred Liebmann Technische Universit¨atM¨unchen Chair of Optimal Control Center for Mathematical Sciences, M17 [email protected] November 10, 2015 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Reading List • Pacheco - An Introduction to Parallel Programming (Chapter 1 - 2) { Introduction to computer hardware architecture from the parallel programming angle • Hennessy-Patterson - Computer Architecture - A Quantitative Approach { Reference book for computer hardware architecture All books are available on the Moodle platform! Computer Hardware Architecture 1 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 UMA Architecture Figure 1: A uniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory is the same for all cores in the system! Computer Hardware Architecture 2 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 NUMA Architecture Figure 2: A nonuniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory differs form core to core depending on the proximity of the main memory. This architecture is often used in dual and quad socket servers, due to improved memory bandwidth. Computer Hardware Architecture 3 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Cache Coherence Figure 3: A shared memory system with two cores and two caches What happens if the same data element z1 is manipulated in two different caches? The hardware enforces cache coherence, i.e. consistency between the caches. Expensive! Computer Hardware Architecture 4 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 False Sharing The cache coherence protocol works on the granularity of a cache line. If two threads manipulate different element within a single cache line, the cache coherency protocol is activated to ensure consistency, even if every thread is only manipulating its own data. -

Parallel Processing! 1! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! 2! Suggested Readings! •! Readings! –! H&P: Chapter 7! •! (Over Next 2 Weeks)!

CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! 1! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! 2! Suggested Readings! •! Readings! –! H&P: Chapter 7! •! (Over next 2 weeks)! Lecture 23" Introduction to Parallel Processing! University of Notre Dame! University of Notre Dame! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! 3! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! 4! Processor components! Multicore processors and programming! Processor comparison! vs.! Goal: Explain and articulate why modern microprocessors now have more than one core andCSE how software 30321 must! adapt to accommodate the now prevalent multi- core approach to computing. " Introduction and Overview! Writing more ! efficient code! The right HW for the HLL code translation! right application! University of Notre Dame! University of Notre Dame! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! 6! Pipelining and “Parallelism”! ! Load! Mem! Reg! DM! Reg! ALU ! Instruction 1! Mem! Reg! DM! Reg! ALU ! Instruction 2! Mem! Reg! DM! Reg! ALU ! Instruction 3! Mem! Reg! DM! Reg! ALU ! Instruction 4! Mem! Reg! DM! Reg! ALU Time! Instructions execution overlaps (psuedo-parallel)" but instructions in program issued sequentially." University of Notre Dame! University of Notre Dame! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! CSE 30321 – Lecture 23 – Introduction to Parallel Processing! Multiprocessing (Parallel) Machines! Flynn#s -

Current Trends in High Performance Computing

Current Trends in High Performance Computing Chokchai Box Leangsuksun, PhD SWEPCO Endowed Professor*, Computer Science Director, High Performance Computing Initiative Louisiana Tech University [email protected] 1 *SWEPCO endowed professorship is made possible by LA Board of Regents Outline • What is HPC? • Current Trends • More on PS3 and GPU computing • Conclusion 12 December 2011 2 1 Mainstream CPUs • CPU speed – plateaus 3-4 Ghz • More cores in a single chip 3-4 Ghz cap – Dual/Quad core is now – Manycore (GPGPU) • Traditional Applications won’t get a free rides • Conversion to parallel computing (HPC, MT) This diagram is from “no free lunch article in DDJ 12 December 2011 3 New trends in computing • Old & current – SMP, Cluster • Multicore computers – Intel Core 2 Duo – AMD 2x 64 • Many-core accelerators – GPGPU, FPGA, Cell • More Many brains in one computer • Not to increase CPU frequency • Harness many computers – a cluster computing 12/12/11 4 2 What is HPC? • High Performance Computing – Parallel , Supercomputing – Achieve the fastest possible computing outcome – Subdivide a very large job into many pieces – Enabled by multiple high speed CPUs, networking, software & programming paradigms – fastest possible solution – Technologies that help solving non-trivial tasks including scientific, engineering, medical, business, entertainment and etc. • Time to insights, Time to discovery, Times to markets 12 December 2011 5 Parallel Programming Concepts Conventional serial execution Parallel execution of a problem where the problem is represented involves partitioning of the problem as a series of instructions that are into multiple executable parts that are executed by the CPU mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive represented as a partially Problem ordered set exhibiting concurrency. -

System & Service Management

©2010, Thomas Galliker www.thomasgalliker.ch System & Service Management Prozessorarchitekturen Multiprocessing and Multithreading Computer architects have become stymied by the growing mismatch in CPU operating frequencies and DRAM access times. None of the techniques that exploited instruction-level parallelism within one program could make up for the long stalls that occurred when data had to be fetched from main memory. Additionally, the large transistor counts and high operating frequencies needed for the more advanced ILP techniques required power dissipation levels that could no longer be cheaply cooled. For these reasons, newer generations of computers have started to exploit higher levels of parallelism that exist outside of a single program or program thread. This trend is sometimes known as throughput computing. This idea originated in the mainframe market where online transaction processing emphasized not just the execution speed of one transaction, but the capacity to deal with massive numbers of transactions. With transaction-based applications such as network routing and web-site serving greatly increasing in the last decade, the computer industry has re-emphasized capacity and throughput issues. One technique of how this parallelism is achieved is through multiprocessing systems, computer systems with multiple CPUs. Once reserved for high-end mainframes and supercomputers, small scale (2-8) multiprocessors servers have become commonplace for the small business market. For large corporations, large scale (16-256) multiprocessors are common. Even personal computers with multiple CPUs have appeared since the 1990s. With further transistor size reductions made available with semiconductor technology advances, multicore CPUs have appeared where multiple CPUs are implemented on the same silicon chip. -

A Case for NUMA-Aware Contention Management on Multicore Systems

A Case for NUMA-aware Contention Management on Multicore Systems Sergey Blagodurov Sergey Zhuravlev Mohammad Dashti Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University Alexandra Fedorova Simon Fraser University Abstract performance of individual applications or threads by as much as 80% and the overall workload performance by On multicore systems, contention for shared resources as much as 12% [23]. occurs when memory-intensive threads are co-scheduled Unfortunately studies of contention-aware algorithms on cores that share parts of the memory hierarchy, such focused primarily on UMA (Uniform Memory Access) as last-level caches and memory controllers. Previous systems, where there are multiple shared LLCs, but only work investigated how contention could be addressed a single memory node equipped with the single memory via scheduling. A contention-aware scheduler separates controller, and memory can be accessed with the same competing threads onto separate memory hierarchy do- latency from any core. However, new multicore sys- mains to eliminate resource sharing and, as a conse- tems increasingly use the Non-Uniform Memory Access quence, to mitigate contention. However, all previous (NUMA) architecture, due to its decentralized and scal- work on contention-aware scheduling assumed that the able nature. In modern NUMA systems, there are mul- underlying system is UMA (uniform memory access la- tiple memory nodes, one per memory domain (see Fig- tencies, single memory controller). Modern multicore ure 1). Local nodes can be accessed in less time than re- systems, however, are NUMA, which means that they mote ones, and each node has its own memory controller. feature non-uniform memory access latencies and multi- When we ran the best known contention-aware sched- ple memory controllers. -

Lecture 2 Parallel Programming Platforms

Lecture 2 Parallel Programming Platforms Flynn’s Taxonomy In 1966, Michael Flynn classified systems according to numbers of instruction streams and the number of data stream. Data stream Single Multiple Instruction stream stream Instruction Single Multiple SISD SIMD Uniprocessors Processor arrays Pipelined vector processors MISD MIMD Systolic arrays Multiprocessors Multicomputers SISD Machine Example: single CPU computers (serial computer) • Single instruction: Only one instruction stream is acted on by CPU during one clock cycle • Single data: Only one data stream is used as input during one clock cycle • Deterministic execution SIMD Machine (I) • A parallel computer • It typically has a single CPU devoted exclusively to control, a large number of subordinate ALUs, each with its own memory and a high- bandwidth internal network. • Control CPU broadcasts an instruction to all subordinate ALUs, and each of the subordinate ALUs either executes the instruction or it is idle. • Example: CM-1, CM-2, IBM9000 SIMD Machine (2) Control CPU ALU 0 ALU 1 ALU p Mem 0 Mem 1 Mem p Interconnection network SIMD Machine (3) From Introduction to Parallel Computing MIMD Machine (I) • Most popular parallel computer architecture • Each processor is a full-fledged CPU with both a control unit and an ALU. Thus each CPU is capable of executing its own program at its own space. • Execution is asynchronous. Processors can also be specifically programmed to synchronize with each other. • Examples: networked parallel computers, symmetric multiprocessor (SMP) computer. MIMD Machine (II) Load A(1) call func Load B(1) X = Y*Z C(1) = A(1)*B(1) Sum = X^2 time Store C(1) call subroutine1(i) … Next instruction Next instruction CPU 0 CPU 1 Further classification according to memory access: • Shared-memory system • Distributed-memory system (Message-passing) Shared-Memory MIMD Machine (I) • Multiple processors can operate independently, but share the same memory resources (a global address space). -

Lecture 1 Parallel Computing Architectures

Lecture 1 Parallel Computing Architectures Dr. Wilson Rivera ICOM 6025: High Performance Computing Electrical and Computer Engineering Department University of Puerto Rico Outline • Goal: Understand parallel computing fundamental concepts – HPC challenges – Flynn’s Taxonomy – Memory Access Models – Multi-core Processors – Graphics Processor Units – Cluster Infrastructures – Cloud Infrastructures ICOM 6025: High Performance Computing 2 HPC Challenges Physics of high-temperature Protein structure and function Global simulation superconducting cuprates for cellulose-to-ethanol conversion of CO2 dynamics Optimization of plasma heating Fundamental instability Next-generation combustion systems for fusion experiments of supernova shocks devices burning alternative fuels Slide source: Thomas Zaharia HPC Challenges Capacity: LES Available # of Overnight Computational Loads cases run Capacity [Flop/s] Unsteady RANS 21 102 1 Zeta (10 ) 3 18 10 RANS Low 1 Exa (10 ) Speed 104 15 x106 RANS HigH 1 Peta (10 ) Speed 5 12 10 “Smart” use of HPC power: 1 Tera (10 ) • Algorithms • Data mining 6 10 • knowledge 1 Giga (109) 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 Aero Real time Data CFD-based CFD-based HS Optimisation CFD based Set LOADS Full MDO noise Design & CFD-CSM in flight & HQ simulation simulation Capability achieved during one night batch Courtesy AIRBUS France HPC Challenges High Resolution Climate Modeling on NERSC-3 – P. Duffy, et al., LLNL ICOM 6025: High Performance Computing 5 HPC Challenges https://computation.llnl.gov/casc/projects/.../climate_2007F.pdf -

Multicore and Multiprocessor Systems: Part I

Chapter 3 Multicore and Multiprocessor Systems: Part I Jens Saak Scientific Computing II 45/348 Symmetric Multiprocessing Definition (Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP)) The situation where two or more identical processing elements access a shared periphery (i.e., memory, I/O,. ) is called symmetric multiprocessing or simply (SMP). The most common examples are Multiprocessor systems, Multicore CPUs. Jens Saak Scientific Computing II 46/348 Interconnect Memory Hierarchy Basic Memory Layout Main Memory system bus I/O cache cache P1 ::: Pn Figure: Schematic of a general parallel system Jens Saak Scientific Computing II 47/348 one physical memory resource, is shared among all processing units, all having uniform access to it. Especially that means that all memory locations can be requested by all processors at the same time scale, independent of which processor preforms the request and which chip in the memory holds the location. Local caches one the single processing units are allowed. That means classical multicore chips are an example of a UMA system. Memory Hierarchy Uniform Memory Access (UMA) UMA is a shared memory computer model, where Jens Saak Scientific Computing II 48/348 is shared among all processing units, all having uniform access to it. Especially that means that all memory locations can be requested by all processors at the same time scale, independent of which processor preforms the request and which chip in the memory holds the location. Local caches one the single processing units are allowed. That means classical multicore chips are an example of a UMA system. Memory Hierarchy Uniform Memory Access (UMA) UMA is a shared memory computer model, where one physical memory resource, Jens Saak Scientific Computing II 48/348 all having uniform access to it. -

Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA)

Non-uniform memory access (NUMA) • Memory access between processor core to main memory is not uniform. • Memory resides in separate regions called “NUMA domains.” • For highest performance, cores should only access memory in its nearest NUMA domain. Memory buses and controllers • Pre-2008: Front side bus • Post-2008: QuickPath interconnect Front Side Bus (FSB) and Multicore • FSB was used up to the Core microarch. (2008) • Memory access by many cores or sockets across the FSB is a bottleneck Hypertransport & QuickPath Interconnect • AMD HyperTransport (2003) Intel QuickPath Interconnect (2008) • Memory controller now on the CPU • Memory access is now non-uniform FSB vs QPI UMA = Uniform Memory Access NUMA = Non-Uniform Memory Access SMP = Symmetric MultiProcessor Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) • NUMA architectures support higher aggregate bandwidth to memory than UMA architectures • “Trade-off” is non-uniform memory access • Can NUMA effects be observed? • Locality domain: a set of processor cores and its locally connected memory (a.k.a. locality “node”) • View the NUMA structure (on Linux): numactl --hardware numactl can also be used to control NUMA behavior NUMA • How does the OS decide where to put data? • How does OS decide where to place the threads? • Ref: Hager and Wellein, Sec 4.2, Chap 8, App A • Ref: Xeon Phi book, Sec 4.4.5 Page placement by first touch • A page is placed in the locality region of the processor that first touches it (not when memory is allocated) • If there is no memory in that locality domain, then another region is used • Other policies are possible (e.g., set preferred locality domain, or round-robin, using numactl) numactl – set memory affinity numactl [--interleave=nodes] [--preferred=node] [--membind=nodes] [--localalloc] <command> [args] .. -

Multiprocessing: Architectures and Algorithms

C SCI 360 Computer Architecture 3 Prof. Stewart Weiss Multiprocessing: Architectures and Algorithms Introduction Scientific advancement requires computational modeling to test hypotheses. Often it is impossible, too difficult, or too time-consuming to do actual physical experiments. Instead computer simulations are done. Some problems are so complex that they take too long to solve using ordinary computers. These have been called the "grand challenges" of science (Levin 1989) as described in the so-called 'blue book' (NSF, 1991). Ten Grand Challenge problems were defined in the blue book, falling into the following categories: • Ocean circulation • Climate modelling • Fluid Turbulence • Pollution dispersion • Human genome (completed in 2003) • Quantum chromodynamics • Semiconductor modeling • Superconductor modeling • Combustion systems • Vision and cognition Most scientific problems such as these must be solved numerically. A numerical solution is one that solves a problem by numerical approximation, which is an algorithm that computes an approximate answer by numerical means. Simple equations often have analytical solutions. An analytical solution is one that expresses the variables whose value is to be determined as a function of its independent variables. For example, the area of a circle can be found if the radius is known, using the formula a=π*r2. More often than not, there is no analytical solution to a problem. For example, the indefinite integral of the function e^(-x^2) has no analytical solution. It must be solved by numerical approximation. A simple example of numeric approximation is the trapezoidal method of integration, in which the range of the integral is divided into equal width trapezoids and the areas of these trapezoids are computed and summed.