Non-Standard Language Use in Performing Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

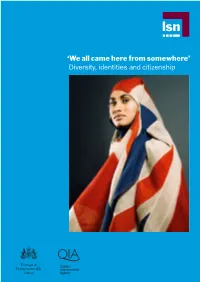

'We All Came Here from Somewhere'

‘We all came here from somewhere’ Diversity, identities and citizenship We all came here from somewhere: Diversity, identities and citizenship is part of a series of support materials produced by the Post-16 Citizenship Development Programme. The programme is managed by the Learning and Skills Network (LSN) and is funded by the Quality Improvement Agency (QIA). Published by the Learning and Skills Network www.LSNeducation.org.uk The Learning and Skills Network is registered with the Charity Commissioners. Comments on the pack and other enquiries should be sent to: Post-16 Citizenship Team Learning and Skills Network Regent Arcade House 19–25 Argyll Street London W1F 7LS Tel: 020 7297 9186 Fax: 020 7297 9242 Email: [email protected] ISBN 1-84572-477-1 CIMS 062482MP © Crown Copyright 2006 Printed in the UK Extracts from these materials may be reproduced for non-commercial educational or training purposes on condition that the source is acknowledged. Otherwise, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, chemical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Information such as organisation names, addresses and telephone numbers, as well as email and website addresses, has been carefully checked before printing. Because this information is subject to change, the Learning and Skills Network cannot guarantee its accuracy after publication. The views expressed in this pack are not necessarily held by the LSN or the QIA. Cover photograph: www.slashstroke.com Typesetting and artwork by Em-Square Limited: www.emsquare.co.uk ‘We all came here from somewhere’ Diversity, identities and citizenship Acknowledgements We are grateful to Benjamin Zephaniah for contributing the foreword to this pack and for permission to reproduce extracts from his work in Activities 4 and 7 (see References and Resources page 49). -

Antisemitism in the Palestine Solidarity Campaign

Beyond the Great Divide Investigates… Antisemitism in the Palestine Solidarity Campaign THE PALESTINE SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN DELEGATING HATE pg. 2 COLLIER: PSC DOSSIER FEBRUARY 2017 www.david-collier.com INDEX Summary 4 The PSC 5 Research 6 Antisemitism 7 BRANCHES Bristol 9-12 Cardiff 13-16 Chester 17 Durham 18-19 Jersey 20-21 London - Merton 23-30 London – Richmond & Kingston 31-36 London – West London 37-38 Luton 39-42 Medway 43 Norwich 44-46 St Ives Cornwall 47 Peterborough 48-50 Reading 51-53 Southport & Formby 54-56 West Midlands 57-61 Wolves 62 CASE STUDY Case Study – London 6th Feb 2017 63-73 Statistical breakdown 74 Conclusion 75 Support the research 76 Appendix 1 PSC Partners 77 Appendix 2 Sample links 78-79 pg. 3 COLLIER: PSC DOSSIER FEBRUARY 2017 www.david-collier.com Summary Although it claims to be concerned with human rights, the Palestine Solidarity Campaign is not a movement of peace, but rather a group that seeks to push Palestinian political ambitions. As part of ongoing research into antisemitism within the UK, I have been following the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign closely for over two years. I have gone to many events, different branches and attended their AGM. Antisemitism has been present consistently. Not an antisemitism that is explained away as a slightly exaggerated description of Israel’s activity, but hard-core ‘Jewish global domination’ type. At these events, I have engaged in conversations with PSC members about their belief about global Jewish control. Analysing online activity of PSC activists at each individual branch, and then culminating in an intensive analysis of ideological drivers of activists at a mass protest, this research suggests that over 40% of all public PSC protest activity is driven by antisemitic motivation. -

An Interview with Benjamin Zephaniah

Kunapipi Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 15 2004 An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah Eric Doumerc Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doumerc, Eric, An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah, Kunapipi, 26(1), 2004. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol26/iss1/15 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah Abstract An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol26/iss1/15 138 138 ERIC DOUMERC ERIC DOUMERC An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah ED Could you first tell me about your background and where you come from? ED Could you first tell me about your background and where you come from? What was your childhood like? What was it like to grow up in England? What was your childhood like? What was it like to grow up in England? Do you feel English, West Indian, both or neither? Do you feel English, West Indian, both or neither? BZ Well, I was born in England. I was born in the city of Birmingham. What BZ Well, I was born in England. I was born in the city of Birmingham. What was my childhood like? It was a very rough area; I remember many of the was my childhood like? It was a very rough area; I remember many of the buildings, much of the area was still flattened because of the war. -

The Importance of the Poetry Book in the Digital

The Importance Of The Poetry Book In The Digital Age How Far Digital Technology Has Influenced Contemporary Poetry And The Status Of The Poetry Book & The Birth of Romance A Poetry Collection A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing at the University of Birmingham by Philip Monks Submitted 27th September 2017 This corrected version 1st March 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT An examination through the creation and curation of a printed poetry collection, together with other practice-based and wider research, of how far digital technology has influenced contemporary poetry and the status of the poetry book. Personal practice is considered and analysed and, from this, and research leading out from this, a more general survey provided of the impact of digital technology on the poet’s persona, the creation of the poems themselves and on their dissemination. These wider issues, and the practice-based research that underlies them, inform the specific consideration of the extent to which digital technology has affected the nature and importance of the single collection poetry book in the early part of the twenty-first century. -

Breaking New Ground: Celebrating

BREAKING NEW GROUND: CELEBRATING BRITISH WRITERS & ILLUSTRATORS OF COLOUR BREAKING NEW GROUND: Work for New Generations BookTrust Contents Represents: 12 reaching more readers by BookTrust Foreword by My time with 5 Speaking Volumes children’s Winter Horses by 14 literature by 9 Uday Thapa Magar Errol Lloyd Our Children Are 6 Reading by Pop Up Projects Reflecting Grandma’s Hair by Realities by Ken Wilson-Max 17 10 the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education Feel Free by Irfan Master 18 Authors and Illustrators by Tiles by Shirin Adl 25 62 Location An Excerpt from John Boyega’s 20 Paper Cup by Full List of Authors Further Reading Catherine Johnson and Illustrators 26 63 and Resources Weird Poster by Author and Our Partners Emily Hughes Illustrator 23 28 Biographies 65 Speaking Volumes ‘To the woman crying Jon Daniel: Afro 66 24 uncontrollably in Supa Hero the next stall’ by 61 Amina Jama 4 CELEBRATING BRITISH WRITERS & ILLUSTRATORS OF COLOUR BREAKING NEW GROUND clear in their article in this publication, we’re in uncertain times, with increasing intolerance and Foreword xenophobia here and around the world reversing previous steps made towards racial equality and social justice. What to do in such times? The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education and BookTrust, who have also contributed to this brochure, point to new generations as the way forward. Research by both organisations shows that literature for young people is even less peaking Volumes is run on passion contribution to the fight for racial equality in the representative of Britain’s multicultural society and a total commitment to reading as arts and, we hoped, beyond. -

What to Do Today

What to do today IMPORTANT Parent or Carer – Read this page with your child and check that you are happy with what they have to do and any weblinks or use of internet. 1. Read about experiences of racism • Read My Experience – Asim Chaudhry. • Fill in the column for Asim on Experience Summary. • Now read My Experience – Claire Heuchan. • Fill in the column for Claire on Experience Summary. 2. Present a story in words and pictures • Watch Balraj’s Story: https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/49613514 • Use words and pictures to summarise Balraj’s Story. 3. Read about challenging racism • Work with a grown-up to read How can you challenge racism? written by Claire Heuchan. • Discuss what you have read with the grown-up. Which of these ideas is most relevant? How does challenging racism make you feel? Nervous, hopeful or a bit of both? Well done. Talk to a grown-up about what you have learnt today. Try this extra activity Can you make a presentation of Asim or Claire’s story (or both), using words and pictures? My Experience by Asim Chaudhry Just a headache It was the summer of '98. I was 11 years old. The World Cup was on and I was at my local park in Feltham, West London, playing football in my new football boots with my best friend, Asad. Before I share this experience let me give you some context about what football meant to us when we were kids. It was our life! In the morning on the way to school we would kick the ball to each other, at times it would go on the road and we would get shouted and beeped at by angry morning commuters. -

Pioneers & Champions

WINDRUSH PIONEERS & CHAMPIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS WINDRUSH PIONEERS Windrush Foundation is very grateful for the contributions Preface 4 David Dabydeen, Professor 82 to this publication of the following individuals: Aldwyn Roberts (Lord Kitchener) 8 David Lammy MP 84 Alford Gardner 10 David Pitt, Lord 86 Dr Angelina Osborne Allan Charles Wilmot 12 Diana Abbott MP 88 Constance Winifred Mark 14 Doreen Lawrence OBE, Baroness 90 Angela Cobbinah Cecil Holness 16 Edna Chavannes 92 Cyril Ewart Lionel Grant 18 Floella Benjamin OBE, Baroness 94 Arthur Torrington Edwin Ho 20 Geoff Palmer OBE, Professor Sir 96 Mervyn Weir Emanuel Alexis Elden 22 Heidi Safia Mirza, Professor 98 Euton Christian 24 Herman Ouseley, Lord 100 Marge Lowhar Gladstone Gardner 26 James Berry OBE 102 Harold Phillips (Lord Woodbine) 28 Jessica Huntley & Eric Huntley 104 Roxanne Gleave Harold Sinson 30 Jocelyn Barrow DBE, Dame 106 David Gleave Harold Wilmot 32 John Agard 108 John Dinsdale Hazel 34 John LaRose 110 Michael Williams John Richards 36 Len Garrison 112 Laurent Lloyd Phillpotts 38 Lenny Henry CBE, Sir 114 Bill Hern Mona Baptiste 40 Linton Kwesi Johnson 116 42 Cindy Soso Nadia Evadne Cattouse Mike Phillips OBE 118 Norma Best 44 Neville Lawrence OBE 120 Dione McDonald Oswald Denniston 46 Patricia Scotland QC, Baroness 122 Rudolph Alphonso Collins 48 Paul Gilroy, Professor 124 Verona Feurtado Samuel Beaver King MBE 50 Ron Ramdin, Dr 126 Thomas Montique Douce 52 Rosalind Howells OBE, Baroness 128 Vincent Albert Reid 54 Rudolph Walker OBE 130 Wilmoth George Brown 56 -

Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala's “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique

Williams, J. A. (2017). Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala's 'The Thieves Banquet' and Neocolonial Critique. Popular Music and Society, 40(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Taylor & Francis at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Popular Music and Society ISSN: 0300-7766 (Print) 1740-1712 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpms20 Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique Justin A. Williams To cite this article: Justin A. Williams (2016): Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique, Popular Music and Society, DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 29 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 34 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpms20 Download by: [University of Bristol] Date: 14 October 2016, At: 02:13 POPULAR MUSIC AND SOCIETY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1230457 OPEN ACCESS Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique Justin A. -

Jeremy Corbyn Popular Front Lib'n Palestine Southampton Antifa Mick Antoniw Merseyside AFN Bristol Anti-Fascists Keith Birch UNISON Steve Turner UNITE

Paul Simpson POSTMODERN NEO-MARXISM Richard Rorty RIP Michel Foucault RIP Alex Craven Max Shanly Norwich N Newham Aberconwy Stanley Fish Ben Sellers Pudsey Rugby Jacques Derrida RIP Norwich N York Lewes York Outer Pudsey Southwark RED LABOUR Newham Shipley Tatton Rugby Aberconwy Salford, Tatton Truro Haringey Migrant issues JF Lyotard RIP Lewes NW Durham Harrow East Lewisham Corbyn's COMMUNITY CAMPAIGNTruro & Falmouth UNIT Marsha-Jane Thompson Shipley Migrant issues Milton Keynes N Stoke-on-Trent N Milton Keynes N Harrow E Haringey Redruth Northampton N Lewisham Fredric Jameson Northampton N Wavertree Broxtowe Laura Pidcock MP Stoke N Redruth James Butler Wavertree Aaron Bastani Project 17 The Word Broxtowe MOMENTUM KIDS Watford Eleanor Penny Sasha Josette Alan Gibbons Cecile Wright Editor Alan Davies Novara Media Socialism Today Jill Mountford London Labour Briefing Leanora Partington Michael Walker Morning Star Michael Chessum Watford David Harvey Ash Sarkar Director Samuel Tarry The World Transformed = Revolution! Director Marx in the Web Solidarity Chantal Mouffe, Belgium Fisayo Eniolorunda Labour Party Marxists Alena Ivanova Director Worker's Fight Jean-Luc Melenchon, France Anarchist Student Society Dr Pete Campbell The Clarion Christine Shawcroft Socialist View Laura Parker Left Futures Radical Left at SOAS The News Line Tower Hamlets New Politics Halimo Hussein Fiona Lali NUS Scottish Socialist Voice Prof Mark Maslin MOMENTUM Labour Against Private Schools John Ross Class War website World Socialist Web Site China, Chinese Academy -

Benjamin Zephaniah

Benjamin Zephaniah Dr Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah was born on the 15th April 1958 in the Handsworth district of Birmingham, England. His mother was a nurse and originally from Jamica. His father was a postal worker and originally from Barbados. Benjamin is famous for his performance poetry. When he was 22 he moved to London so he could share his poetry with more people. Poems Benjamin attended school until he was 13 years old, he initially found it difficult to read and write. Unhappy with the popular opinion that poetry was only for people who were in school or at university, he started performing his poems so that they were accessible to everyone. The type of poetry that Benjamin performs is ‘dub’ poetry. Dub poetry uses the performer’s voice as a musical instrument. The performer changes the speed and pitch of the poem to give it more a musical sound. Benjamin’s performances became really popular and many people enjoyed his poetry. Causes Many of Benjamin’s poems are about causes that he has strong beliefs about. He has written, performed and published many poems with messages against racism and slavery. Alongside this, he also writes poems about what he calls ‘street politics’. In the early 1980’s he performed some of his poems at demonstrations and outside police stations; this was to argue against homelessness and rising unemployment at the time. As a supporter of animal rights, Benjamin also writes poems which discuss and question the way we treat animals. Books As well as performing his poetry around the world, Benjamin has published his work in several books for both adults and children. -

Rastafari and the Arts

RASTAFARI AND THE ARTS Drawing on literary, musical, and visual representations of and by Rastafari, Darren J. N. Middleton provides an introduction to Rasta through the arts, broadly conceived. The religious underpinnings of the Rasta movement are often over- shadowed by Rasta’s association with reggae music, dub, and performance poetry. Rastafari and the Arts: An Introduction takes a fresh view of Rasta, considering the relationship between the artistic and religious dimensions of the movement in depth. Middleton’s analysis complements current introductions to Afro-Caribbean religions and offers an engaging example of the role of popular culture in illumi- nating the beliefs and practices of emerging religions. Recognizing that outsiders as well as insiders have shaped the Rasta movement since its modest beginnings in Jamaica, Middleton includes interviews with members of both groups, including: Ejay Khan, Barbara Makeda Blake Hannah, Geoffrey Philp, Asante Amen, Reggae Rajahs, Benjamin Zephaniah, Monica Haim, Blakk Rasta, Rocky Dawuni, and Marvin D. Sterling. Darren J. N. Middleton is Honors Faculty Fellow and Professor of Religion in The John V. Roach Honors College, Texas Christian University. He has published eight books, received several teaching awards, and he lives in Fort Worth. This page intentionally left blank RASTAFARI AND THE ARTS An Introduction Darren J. N. Middleton First published 2015 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2015 Taylor & Francis The right of Darren J. N. Middleton to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

RACISM in BENJAMIN ZEPHANIAH SELECTED POEMS THESIS By

RACISM IN BENJAMIN ZEPHANIAH SELECTED POEMS THESIS By: Ririn Wulandari 14320035 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2018 RACISM IN BENJAMIN ZEPHANIAH SELECTED POEMS THESIS Presented to Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang in partial to fulfillment of the requirements for degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S) By: Ririn Wulandari NIM 14320035 Supervisor: Dr. Siti Masitoh, M.Hum 196810202003122001 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2018 i ii iii iv MOTTO If you want to make something for yourself Work harder than everybody else v DEDICATION This Thesis is dedicated to: My Family, My beloved mother and father My one and only sister, Thank you so much for supporting me My Advisor Dr. Siti Masitoh, M.Hum, Thank you so much for guiding me to do my thesis patiencely Nothing can replace you in my life I love you all with all of my heart I am nothing without you vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The researcher expresses her gratitude to Allah SWT. For Her Blessing and Mercy she can accomplish her mini-thesis entitled Racism in Benjamin Zephaniah’s Selected Poem as the requirement for the Degree of SarjanaSastra. Sholawat and Salam are also delivered toward Rasulullah SAW, who has guided her followers to the rightness. On this occasion, the researcher would like to thank to her family, especially her beloved parents Father and Motherwho have given the finance, facility, prayer and support in studying at the Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University of Malang. Thus, I want to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr.