'Dingzhou: the Story of an Unfortunate Tomb'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dingzhou: the Story of an Unfortunate Tomb

DINGZHOU: THE STORY OF AN UNFORTUNATE TOMB Paul van Els, Leiden University Abstract In 1973, Chinese archaeologists excavated a tomb of considerable dimensions near Dingzhou. This tomb, which dates to the Former Han dynasty, yielded a rich array of funerary furnishings, including jadeware, goldware, bronzeware, lacquerware and a large cache of inscribed bamboo strips, with significant potential for study. Sadly, though, the tomb and its contents were struck by several disastrous events (robbery, fire, earthquake). These disasters severely affected the quantity and quality of the find and may have tempered scholarly enthusiasm for Dingzhou, which remains little-known to date. This paper, the first English-language specialized study of the topic, provides an overall account of the Dingzhou discovery; it draws attention to fundamental issues regarding the tomb (e.g. its date) and the manuscripts (e.g. their transcription); and it explores the significance of the tomb and its contents, and their potential importance for the study of early imperial Chinese history, philosophy, literature and culture. Introductory Remarks In 1973, a team of Chinese archaeologists excavated a Former Han dynasty tomb near Dingzhou ᅮᎲ in Hebei Province ⊇࣫ⳕ.1 In eight months of excavation, from May to December, the team revealed a tomb of considerable dimensions and brought to light a rich array of funerary furnishings, including several manu- scripts, with significant potential for the study of early imperial Chinese history, philosophy, literature and culture. Sadly, the discovery did not achieve its full potential. In the three decades that have passed since, studies of the Dingzhou find have come to influence our understanding of a few philosophical texts (e.g. -

49232-001: Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Air Quality Improvement Program

Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Air Quality Improvement–Hebei Policy Reforms Program (RRP PRC 49232) SECTOR ASSESSMENT: ENVIRONMENT (AIR POLLUTION) Sector Road Map A. Sector Performance, Problems, and Opportunities 1. Air pollution problems in the PRC. Decades of unsustainable economic growth in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have resulted in severe degradation of the air, water and soil quality throughout the country. In 2014, 74 of PRC’s prefecture-level and higher level cities recorded annual concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exceeding the national standard of 35 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3) by 83%, with 7 of the 10 most polluted cities in the PRC located in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) region.1 High levels of air pollution are among the first environmental problems that the PRC’s leadership has addressed with an unprecedented scale of reforms and actions which include the first “Action Plan of Pollution Prevention and Control” (hereinafter CAAP) outlining targets to be achieved in 2013–2015 in key regions, a new vision for the PRC’s urbanization which emphasizes improved ecological environment in cities, and a new environmental protection law unleashing long-needed reforms in the government performance assessment system. 2. Air quality and emissions in Hebei Province. Hebei province (Hebei) surrounds Beijing and Tianjin Municipalities, bordering Bohai bay to the east. Despite its advantageous geographical position, Hebei’s resources driven and heavy industry based economy has made the province lag behind other coastal provinces like Jiansgu and Zhejiang in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) and overall economic performance. In 2014, Hebei’s GDP totaled CNY2.94 trillion with a per capita GDP of CNY39,846. -

Commentaar Van the Epoch Times Op De Communistische Partij

Commentaar van The Epoch Times op de Communistische Partij Deel 5 – De samenzwering van Jiang Zemin met de Chinese Communistische Partij om Falun Gong te vervolgen Waarom wordt Falun Gong, een vorm van Qigong die gebaseerd is op de principes van “Waarachtigheid, Mededogen en Verdraagzaamheid” en die wereldwijd beoefend wordt in meer dan zestig landen, alleen in China vervolgd en nergens anders ter wereld? Wat is de heimelijke verstandhouding tussen Jiang Zemin en de CCP in deze vervolging? Voorwoord Mevr. Zhang Fuzhen, leeftijd ongeveer 38 jaar, was een werknemer van het Xianhe park te Pingdu, in de provincie Shandong, China. Ze ging naar Beijing in november 2000 om er tegen de vervolging van Falun Gong in beroep te gaan en werd later door de autoriteiten ontvoerd. Volgens interne bronnen folterde en vernederde de politie Zhang Fuzhen, werden haar kleren uitgetrokken en werd haar hoofd volledig kaalgeschoren. Ze bonden haar vast aan een bed met haar vier ledematen uitgerekt en zij werd aldus gedwongen zichzelf op het bed te ontlasten. Later gaf de politie haar een injectie met een onbekende giftige substantie. Na de injectie had Zhang zoveel pijn dat zij bijna krankzinnig werd. Op het bed worstelde ze met enorme pijn tot zij overleed. Het hele proces werd gadegeslagen door de lokale functionarissen van het ‘6-10 Bureau’. (Uittreksel uit een rapport van 31 mei 2004 van de Clearwisdom website)[1] Tirannie vastgelegd op film: Politieagenten in burger en in uniform arresteren ca. 10 Falun Gong beoefenaars Mevr. Yang Lirong, 34, was afkomstig uit Beimen die voor een vreedzame betoging voor het einde van de Straat, Dingzhou, Baoding Prefectuur, in de vervolging van Falun Gong naar het Plein van de provincie Hebei. -

Three Kingdoms Unveiling the Story: List of Works

Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Japan-China Cultural Exchange Agreement List of Works Organizers: Tokyo National Museum, Art Exhibitions China, NHK, NHK Promotions Inc., The Asahi Shimbun With the Support of: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, NATIONAL CULTURAL HERITAGE ADMINISTRATION, July 9 – September 16, 2019 Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan With the Sponsorship of: Heiseikan, Tokyo National Museum Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd., Notes Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Co.,Ltd., MITSUI & CO., LTD. ・Exhibition numbers correspond to the catalogue entry numbers. However, the order of the artworks in the exhibition may not necessarily be the same. With the cooperation of: ・Designation is indicated by a symbol ☆ for Chinese First Grade Cultural Relic. IIDA CITY KAWAMOTO KIHACHIRO PUPPET MUSEUM, ・Works are on view throughout the exhibition period. KOEI TECMO GAMES CO., LTD., ・ Exhibition lineup may change as circumstances require. Missing numbers refer to works that have been pulled from the JAPAN AIRLINES, exhibition. HIKARI Production LTD. No. Designation Title Excavation year / Location or Artist, etc. Period and date of production Ownership Prologue: Legends of the Three Kingdoms Period 1 Guan Yu Ming dynasty, 15th–16th century Xinxiang Museum Zhuge Liang Emerges From the 2 Ming dynasty, 15th century Shanghai Museum Mountains to Serve 3 Narrative Figure Painting By Qiu Ying Ming dynasty, 16th century Shanghai Museum 4 Former Ode on the Red Cliffs By Zhang Ruitu Ming dynasty, dated 1626 Tianjin Museum Illustrated -

Inter-Metropolitan Land-Price Characteristics and Patterns in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration in China

sustainability Article Inter-Metropolitan Land-Price Characteristics and Patterns in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration in China Can Li 1,2 , Yu Meng 1, Yingkui Li 3 , Jingfeng Ge 1,2,* and Chaoran Zhao 1 1 College of Resource and Environmental Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 2 Hebei Key Laboratory of Environmental Change and Ecological Construction, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 3 Department of Geography, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0311-8078-7636 Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 25 August 2019; Published: 29 August 2019 Abstract: The continuous expansion of urban areas in China has increased cohesion and synergy among cities. As a result, the land price in an urban area is not only affected by the city’s own factors, but also by its interaction with nearby cities. Understanding the characteristics, types, and patterns of urban interaction is of critical importance in regulating the land market and promoting coordinated regional development. In this study, we integrated a gravity model with an improved Voronoi diagram model to investigate the gravitational characteristics, types of action, gravitational patterns, and problems of land market development in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration region based on social, economic, transportation, and comprehensive land-price data from 2017. The results showed that the gravitational value of land prices for Beijing, Tianjin, Langfang, and Tangshan cities (11.24–63.35) is significantly higher than that for other cities (0–6.09). The gravitational structures are closely connected for cities around Beijing and Tianjin, but loosely connected for peripheral cities. -

China's Forbidden Zones

China’s Forbidden Zones Shutting the Media out of Tibet and Other “Sensitive” Stories Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-357-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-357-9 China’s Forbidden Zones Shutting the Media out of Tibet and Other “Sensitive” Stories Map of China and Tibet....................................................................................................... 1 I. Summary......................................................................................................................2 Key Recommendations ................................................................................................... 6 Methodology ...................................................................................................................7 II. Background: Longstanding Media Freedom Constraints in China ..................................9 Constraints on Media Freedom ....................................................................................... 9 Government Promises of Media Freedom for the Olympics ............................................13 Assessment of Media Freedom since August 2007 ....................................................... -

Kathleen Hall: Dr. Bethune's Angel by TOM NEWNHAM

Kathleen Hall: Dr. Bethune's Angel By TOM NEWNHAM (This article appeared in China Today in 1997) GENERAL "Vinegar'' Joe Stilwell was the top U.S. military man in China during World War II. He once stated that North China, where Japanese forces numbering about two million were held up for eight years, was the pivotal theater in the Pacific War. I am sure he was right, and that this fact played a major part in saving Australia and my country, New Zealand, from invasion by the Japanese. It was the Communist 8th Route Army, led by Mao Zedong, which bore the brunt of the fighting from its base in the Jin-Cha-Ji Border Area. This is the Wutai Mountain Area, where the provinces of Hebei, Shanxi, and the former province of Chahar met. Mao appointed a Canadian, Dr. Norman Bethune, to be in charge of medical services. Bethune had to start virtually from scratch at a time when the region was totally surrounded by the Japanese. He learned that a New Zealand missionary nurse, along with two Chinese nurses, was running a tiny cottage hospital in "no-man's land'' on the edge of Japanese-held territory. He decided to ask for her help. That night Bethune wrote in his diary, "I have met an angel...Kathleen Hall, of the Anglican Church Mission here...She will go to Peking, buy up medical supplies, and bring them back to her mission...for us! If she isn't an angel, what does the word mean?'' During the event, Kathleen made numerous trips to Beijing and brought back great quantities of supplies, first by train to Baoding and Dingzhou, and then by mule trains into the mountains. -

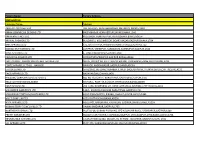

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

The Dingzhou Wenzi 23

The Dingzhou Wenzi 23 Chapter 2 The Dingzhou Wenzi Some 277 bamboo fragments of the Dingzhou find have been identified as remnants of a manuscript entitled Wenzi. A description of the manuscript was published in the August 1981 issue of Wenwu. Despite its brief nature, the description was greatly appealing to scholars. This is because the Wenzi is a controversial text in its transmitted form (the only form in which it was known at the time), and it was hoped that the manuscript would shed light on the controversy. However, their patience was tested as the transcription of the excavated Wenzi manuscript was not published until fourteen years later, in the December 1995 issue of Wenwu. That publication drew even more scholarly attention to the Wenzi, for it enabled access to the transcribed text of the earli- est known Wenzi manuscript to date. 2.1 The Manuscript Judging by the handful of tracings published together with the transcribed text of the excavated Wenzi, the 277 bamboo fragments vary in length from barely 2 cm to just under 21 cm, and in width from circa 0.4 to 0.8 cm. When still in the hands of their Western Han dynasty reader, the strips probably measured circa 21 by 0.8 cm, the length of which approximates nine “inches” (cun 寸) in Han dynasty standards.1 This means that the Wenzi bamboo strips were distinctly longer than those of other manuscripts found in the tomb, such as the Rujiazhe yan (11.5 cm) and the Lunyu (16.2 cm).2 If the lengths of the fragments discov- ered are representative of the buried manuscripts, then their different lengths may point to a hierarchy of texts, with longer bamboo strips reserved for texts 1 For an overview of Han dynasty weights and measures, see Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe, eds., The Cambridge History of China. -

Distribution, Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Aegilops Tauschii Coss. in Major Whea

Supplementary materials Title: Distribution, Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Aegilops tauschii Coss. in Major Wheat Growing Regions in China Table S1. The geographic locations of 192 Aegilops tauschii Coss. populations used in the genetic diversity analysis. Population Location code Qianyuan Village Kongzhongguo Town Yancheng County Luohe City 1 Henan Privince Guandao Village Houzhen Town Liantian County Weinan City Shaanxi 2 Province Bawang Village Gushi Town Linwei County Weinan City Shaanxi Prov- 3 ince Su Village Jinchengban Town Hancheng County Weinan City Shaanxi 4 Province Dongwu Village Wenkou Town Daiyue County Taian City Shandong 5 Privince Shiwu Village Liuwang Town Ningyang County Taian City Shandong 6 Privince Hongmiao Village Chengguan Town Renping County Liaocheng City 7 Shandong Province Xiwang Village Liangjia Town Henjin County Yuncheng City Shanxi 8 Province Xiqu Village Gujiao Town Xinjiang County Yuncheng City Shanxi 9 Province Shishi Village Ganting Town Hongtong County Linfen City Shanxi 10 Province 11 Xin Village Sansi Town Nanhe County Xingtai City Hebei Province Beichangbao Village Caohe Town Xushui County Baoding City Hebei 12 Province Nanguan Village Longyao Town Longyap County Xingtai City Hebei 13 Province Didi Village Longyao Town Longyao County Xingtai City Hebei Prov- 14 ince 15 Beixingzhuang Town Xingtai County Xingtai City Hebei Province Donghan Village Heyang Town Nanhe County Xingtai City Hebei Prov- 16 ince 17 Yan Village Luyi Town Guantao County Handan City Hebei Province Shanqiao Village Liucun Town Yaodu District Linfen City Shanxi Prov- 18 ince Sabxiaoying Village Huqiao Town Hui County Xingxiang City Henan 19 Province 20 Fanzhong Village Gaosi Town Xiangcheng City Henan Province Agriculture 2021, 11, 311. -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

CD151 Promotes Colorectal Cancer Progression by a Crosstalk Involving CEACAM6, LGR5 and Wnt Signaling Via Tgfβ1

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, Vol. 17 848 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Biological Sciences 2021; 17(3): 848-860. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.53657 Research Paper CD151 promotes Colorectal Cancer progression by a crosstalk involving CEACAM6, LGR5 and Wnt signaling via TGFβ1 Tao Yang1#, Huibing Wang2#, Meng Li2, Linqi Yang2, Yu Han3, Chao Liu4, Baowen Zhang5, Mingfa Wu6, Gang Wang7, Zhenya Zhang8, Wenqi Zhang9, Jianming Huang1, Huaxing Zhang10, Ting Cao1, Pingping Chen2 and Wei Zhang2 1. Center for Medical Research and Innovation, Shanghai Pudong Hospital, Fudan University Pudong Medical Center, Shanghai, 201399, China. 2. Department of Pharmacology, Hebei University of Chinese Medicine, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, 050200, China. 3. Department of Pharmacy, Children's Hospital of Hebei Province, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, 050000, China. 4. Department of Laboratory Animal Science, Hebei Key Lab of Hebei Laboratory Animal Science, Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, 050017, China. 5. Hebei Collaboration Innovation Center for Cell Signaling, Key Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Biology of Ministry of Education, Hebei Key Laboratory of Moleculor and Cellular Biology, College of Life Sciences, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, 050024, China. 6. Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Dingzhou City People's Hospital, Dingzhou, Hebei, 073000, China. 7. Department of Third General Surgery, Cangzhou City People’s Hospital, Cangzhou, Hebei, 061000, China. 8. Department of Second General Surgery, Hebei Medical University Fourth hospital, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, 050011, China. 9. College of Basic Medicine, Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, 500017, China. 10. School of Basic Medical Sciences, Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang 050017, Hebei, China. #These authors contributed equally to this work. Corresponding authors: Wei Zhang (E-mail: [email protected]); Pingping Chen (E-mail: [email protected]).