Multi-Page.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

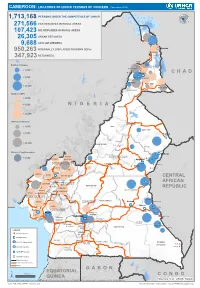

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Evaluation of Some Technologies Developed by the Food Technology Laboratory of the Institute of Agricultural Research for Development: Case of Cocoa, Coffee and Rice

Journal of Agricultural Science; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2016 ISSN 1916-9752 E-ISSN 1916-9760 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Evaluation of Some Technologies Developed by the Food Technology Laboratory of the Institute of Agricultural Research for Development: Case of Cocoa, Coffee and Rice Guemche Sillag Jeanne Irène1, Patience Bongse Kari Andoseh2, Tchamba Joël1 & Pauline Mounjouenpou2 1 The University of Jean Paul II Yaounde, Yaounde, Cameroon 2 Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Yaounde, Cameroon Correspondence: Guemche Sillag Jeanne Irène, The University of Jean Paul II Yaounde, Yaounde, Cameroon. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 24, 2015 Accepted: September 27, 2015 Online Published: December 15, 2015 doi:10.5539/jas.v8n1p195 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jas.v8n1p195 Abstract The cultivation of plant such as cocoa, coffee and rice is practised by a large number of rural Cameroonian populations. Unfortunately, they are the most suffering of malnutrition, food insecurity and poverty. To improve their livelihoods, the Food Technology Laboratory (FTL) has developed some simple and innovative techniques to transform cocoa, coffee and rice and transferred them to producers. This study aims to evaluate the adoption of those innovations by producers. The survey was conducted in five most important markets in Yaoundé and in one pilot village named Bialanguéna. Data were analysed based on a comparison of the state before and after the acquisition of innovative technologies by producers. Changes observed in the food and economic habits were evaluated. The results show that cocoa products are the most adopted ones. Bialanguena women and Yaounde cocoa producers convert some cocoa beans to cocoa powder and cocoa butter for their therapeutic and nutritive needs. -

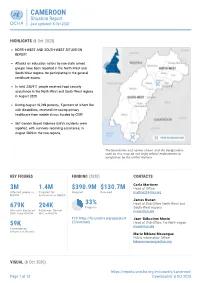

CAMEROON Situation Report Last Updated: 8 Oct 2020

CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 8 Oct 2020 HIGHLIGHTS (8 Oct 2020) NORTH-WEST AND SOUTH-WEST SITUATION REPORT Attacks on education actors by non-state armed groups have been reported in the North-West and South-West regions for participating in the general certificate exams. In total 245,911 people received food security assistance in the North-West and South-West regions in August 2020. During August 10,249 patients, 5 percent of whom live with disabilities, received life-saving primary healthcare from mobile clinics funded by CERF. 567 Gender Based Violence (GBV) incidents were reported, with survivors receiving assistance, in August 2020 in the two regions. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Carla Martinez 3M 1.4M $390.9M $130.7M Head of Office Affected people in Targeted for Required Received [email protected] NWSW assistance in NWSW ! j e r d n , A y James Nunan r r o S 33% Head of Sub-Office North-West and 679K 204K Progress South-West regions Internally displaced Returnees (former [email protected] (IDP) from NWSW IDP) in NWSW FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/9 Jean-Sébastien Munie 27/summary Head of Sub-Office, Far-North region 59K [email protected] Cameroonian refugees in Nigeria Marie Bibiane Mouangue Public information Officer [email protected] VISUAL (8 Oct 2020) https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/cameroon/ Page 1 of 13 Downloaded: 8 Oct 2020 CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 8 Oct 2020 Map of IDP, Returnees and Refugees from the North-West and South-West Regions of Cameroon Source: OCHA, UNHCR, IOM The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

The Dynamics and Implications of the Coffee Economy in Tubah Sub-Division, 1934-2005

International Journal of African and Asian Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2409-6938 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.38, 2017 The Dynamics and Implications of the Coffee Economy in Tubah Sub-Division, 1934-2005 Canute Ambe Ngwa Higher Teacher Training College, Bambili, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon Divine Achenui Nwenfor Department of History, University of Yaounde I, Cameroon Abstract That the coffee economy in Tubah is at a development cul-de-sac and requires an overhaul is unquestionable. The article introduces the sustainable coffee challenge and the circumstances that made the sector unsustainable and suffered a decline in Tubah. It has been argued that coffee economy in Tubah was introduced as a substitute to the legitimate trade and owed its unsustainability and eventual decline to the outbreak of the economic crisis in the 1980s. Such argument is often pegged to the grievances of the poor angry farmers who were victims of the economic crisis and appear to have written off the benefits of the coffee sector on their livelihoods in the past. Contrary to such orthodox, this paper argues that the natural environment of Tubah alongside colonial influence provided the potential for the emergence of the coffee economy. It is further illustrated that coffee cultivation and commercialization mechanisms in Tubah evolved with time and circumstances. The lack of farm subsidies and the fall in the price of the commodity in the world market left the farmers in a state of dilemma. The paper also exposes the view that the coffee economy, in spite its constraints, resulted in beneficial socio- economic mutations in Tubah. -

From Migrants to Nationals, from Nationals To

International Journal of Latest Engineering and Management Research (IJLEMR) ISSN: 2455-4847 www.ijlemr.com || Volume 03 - Issue 06 || June 2018 || PP. 10-19 From Nomads to Nationals, From Nationals to Undesirable Elements: The Case of the Mbororo/Fulani in North West Cameroon 1916-2008 A Historical Investigation Jabiru Muhammadou Amadou (Phd) Higher Teacher Training College Department of History The University of Yaounde 1 Abstract: The Fulani (Mbororo) are a minority group perceived as migrants and strangers by local North West groups who consider themselves their hosts and landlords. They are predominantly nomadic people located almost exclusively within the savannah zone of West and Central Africa. Their original homeland is said to be the Senegambia region. From Senegal, the Fulani continued their movement along side their cattle and headed to Northern Nigeria. Uthman Dan Fodio‟s 19th century jihad movement and epidemic outbreaks force them to move from Northern Nigeria to Northern Cameroon. From Northern Cameroon they moved down South and started penetrating the North West Region in the early 20th century. This article critically examines and considers the case of the Fulani in the North West Region of Cameroon and their recent claims to regional citizenship and minority status. The paper begins by presenting the migration, settlement and ultimate acquisition of the status of nationals by the nomadic cattle Fulani in North West Cameroon. It also analysis the difficulties encountered by this nomadic group to fully integrate themselves into the region. In the early 20th century (more precisely 1916) when they arrived the North West Region, they were warmly received by their hosts. -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST -

Ghana R-PP (Annexes)

Ghana R-PP (Annexes) Annexes Annexes ..................................................................................................... 1 Annex 1a: National Readiness Management Arrangements ..................................................... 2 Annexes for 1b: Stakeholder Consultations Held So Far on the R-PP ......................................... 5 Annex 1b-4: Stakeholder Consultations and Participation Plan (for R-PP Implementation) ............ 31 Annex 2b: REDD Strategy Options ................................................................................. 48 Annex 2c: REDD Implementation Framework .................................................................... 84 Annex 2d: Social and Environmental Impact Assessment ..................................................... 84 Annex 3: Reference Scenario ....................................................................................... 90 Annex 4: Monitoring System ........................................................................................ 90 Annex 6: Program Monitoring and Evaluation ................................................................... 90 Annex 7: Background Paper ........................................................................................ 91 A. SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 91 A. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. 94 A. THE CONTEXT .................................................................................................. -

Masculinity and Female Resistance in the Rice Economy in Meteh/Menchum Valley Bu, North West Cameroon, 1953 – 2005

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 15, No.7, 2013) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania MASCULINITY AND FEMALE RESISTANCE IN THE RICE ECONOMY IN METEH/MENCHUM VALLEY BU, NORTH WEST CAMEROON, 1953 – 2005 Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT Male chauvinism and female reaction in the rice economy in Bu, Menchum Division of North West Cameroon is the subject of this investigation. The greater focus of this paper is how and why this phobia has lessened over the years in favour of female dominion over the rice economy. The point d’appui of the masculine management of the economy and the accentuating forces which have militated against their continuous domination of women in the rice sector have been probed into. Incongruous with the situation hitherto, women have farms of their own bought with their own money accumulated from other economic activities. In addition, they now employ the services of men to execute some defined tasks in the rice economy. From the copious data consulted on the rice economy and related economic endeavours, it is a truism that be it collectively and/or individually, men and women in Bu are responding willingly or not, to the changing power relations between them in the rice economy with implications for sustainable development. Keywords: Masculinity, Female Resistance, Rice Economy, Cameroon, Sustainability 115 INTRODUCTION: RELEVANCE OF STUDY AND CONCEPT OF MASCULINITY Rice is a staple food crop in Cameroon like elsewhere in Africa and other parts of the world. It has become increasingly important part of African diets especially West Africa and where local production has been insufficient due to limited access to credit (Akinbode, 2013, p. -

CAMEROON: North-West and South-West Situation Report No

CAMEROON: North-West and South-West Situation Report No. 12 As of 31 October 2019 This report is produced by OCHA Cameroon in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers 1 – 31 October 2019. The next report will be issued in December. HIGHLIGHTS • 172,372 people benefitted from food and livelihood assistance in October. • 3,136 children received vitamin A and 950 children were vaccinated against measles in October • 112,794 individuals were reached with WASH activities during the reporting period. • 77,510 people have been reached with shelter assistance and 84,895 people have been supported with NFI assistance in the North-West and South-West (NWSW) since January. • 91% of school-aged children are out of school. • The total level of displacement from NWSW stands at over 700,000, including those displaced as refugees in Nigeria as well as in other regions in Cameroon. • Both parties to the conflict continue to breach International Law, including International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law, attacking civilians, schools and civilian health facilities. The health facility in Tole (SW) was destroyed by NSAGs after being used as a base by the Cameroon military. • Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs) as well as criminal groups continue to block humanitarian access with kidnapping of 10 humanitarian workers in October (all released) and demands for ransom are common. Source: OCHA The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on • 1,790 protection incidents were registered in October. Burning of this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the houses predominantly associated with Cameroon military represents United Nations. -

Non-Commercial Use Only

Journal of Public Health in Africa 2011 ; volume 2:e10 Social stigma as an epidemio- lack of self-esteem, tribal stigma and complete rejection by society. From the 480 structured Correspondence: Dr. Dickson S. Nsagha, logical determinant for leprosy questionnaires administered, there were over- Department of Public Health and Hygiene, elimination in Cameroon all positive attitudes to lepers among the study Medicine Programme, Faculty of Health Sciences, population and within the divisions (P=0.0). University of Buea, PO Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. Dickson S. Nsagha,1,2 The proportion of participants that felt sympa- Tel. +237. 77499429.E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Anne-Cécile Z.K. Bissek,3 thetic with deformed lepers was 78.1% [95% 4 confidence interval (CI): 74.4-81.8%] from a Sarah M. Nsagha, Key words: leprosy, social stigma, attitudes, elim- Anna L. Njunda,5 total of 480. Three hundred and ninety nine ination, Cameroon. Jules C.N. Assob,6 (83.1%) respondents indicated that they could Earnest N. Tabah,7 share a meal or drink at the same table with a Acknowledgements: the authors are grateful to Elijah A. Bamgboye,2 deformed leper (95% CI: 79.7-86.5%). Four Mr. Nsagha BN, Mr. Nsagha IG and Late Papa hundred and three (83.9%) participants indi- James Nsagha, who sponsored this study. The Alain Bankole O.O. Oyediran,2 cated that they could have a handshake and authors also thank Mr. Agyngi CT & Mr. Ideng DA Peter F. Nde,1 embrace a deformed leper (95% CI: 80.7- of the Benakuma Health Center; Mr. -

Distortions to Agricultural Incentives in Cameroon

Distortions to Agricultural Incentives Public Disclosure Authorized in Cameroon Ernest Bamou and William A. Masters Public Disclosure Authorized University of Yaoundé II [email protected] Purdue University [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized Agricultural Distortions Working Paper 42, December 2007 This is a product of a research project on Distortions to Agricultural Incentives, under the leadership of Kym Anderson of the World Bank’s Development Research Group. The author is grateful for helpful comments from workshop participants and for funding from World Bank Trust Funds provided by the governments of Ireland, Japan, Public Disclosure Authorized the Netherlands (BNPP) and the United Kingdom (DfID). This Working Paper series is designed to promptly disseminate the findings of work in progress for comment before they are finalized. The views expressed are the authors’ alone and not necessarily those of the World Bank and its Executive Directors, nor the countries they represent, nor of the institutions providing funds for this research project. 1 Distortions to Agricultural Incentives in Cameroon Ernest Bamou and William A. Masters Cameroon is among the more prosperous countries in Africa, thanks to relatively abundant agricultural land and offshore petroleum. These spurred an economic boom from unification of the country in 1972 until 1986, which was followed by a decade of decline from 1986 to 1995 and a limited recovery since then (Appendix Figure 1). In terms of social indicators, primary school enrollment rates fell from nearly 100 percent in the 1980s to 62 percent in 1997 (World Bank 2002), and child mortality rates worsened from 139 per thousand in 1990 to 151 per thousand in 1995, and it was still 149 in 2006 (World Bank 2006, 2008).