VIOLENT EXTREMISM and TERRORISM ONLINE in 2018: the YEAR in REVIEW Maura Conway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideology, Social Basis, Prospects REPORT 2018

European Centre for Democracy Development Center for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications CONTEMPORARY FAR-RIGHTS Right radicalism in Europe: ideology, social basis, prospects REPORT 2018 Athens-London-Berlin-Paris-Moscow-Krakow-Budapest-Kiev-Amsterdam-Roma 1 Editor in Chief and Project Head: Dr. Valery Engel, Chairman of the Expert Council of the European Centre for Tolerance, principal of the Center for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications Authors: Dr. Valery Engel (general analytics), Dr. Jean-Yves Camus (France), Dr. Anna Castriota (Italy), Dr. Ildikó Barna (Hungary), Bulcsú Hunyadi (Hungary), Dr. Vanja Ljujic (Netherlands), Tika Pranvera (Greece), Katarzyna du Val (Poland), Dr. Semen Charny (Russia), Dr. Dmitry Stratievsky (Germany), Ruslan Bortnik (Ukraine), Dr. Alex Carter (UK) Authors thank the Chairman of the European Centre for Tolerance, Mr. Vladimir Sternfeld, for his financial support of the project CONTEMPORARY FAR-RIGHTS Right radicalism in Europe: ideology, social basis, prospects Report “Contemporary far-rights. Right-wing radicalism in Europe: ideology, social base, prospects" is the result of the work of an international team of experts from 10 European countries. The report answers the question of what is the social basis of European right- wing radicalism and what are the objective prerequisites and possible directions for its development. In addition, the authors answer the question of what stays behind the ideology of modern radicalism, what the sources of funding for right-wing radical organizations are, and who their leaders are. Significant part of information is introduced for the first time. © European Center for Democracy Development, 2018 © Center for Monitoring and Comparative Analysis of Intercultural Communications, 2018 © Institute for Ethnic Policy and Inter-Ethnic Relations Studies, 2018 2 Introduction Radicalism is a commitment to the extreme views and concepts of the social order associated with the possibility of its radical transformation. -

Eric Johnson Producer of Recode Decode with Kara Swisher Vox Media

FIRESIDE Q&A How podcasting can take social media storytelling ‘to infinity and beyond’ Eric Johnson Producer of Recode Decode with Kara Swisher Vox Media Rebecca Reed Host Off the Assembly Line Podcast 1. Let’s start out by introducing yourself—and telling us about your favorite podcast episode or interview. What made it great? Eric Johnson: My name is Eric Johnson and I'm the producer of Recode Decode with Kara Swisher, which is part of the Vox Media Podcast Network. My favorite episode of the show is the interview Kara conducted with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg — an in-depth, probing discussion about how the company was doing after the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the extent of its power. In particular, I really liked the way Kara pressed Zuckerberg to explain how he felt about the possibility that his company's software was enabling genocide in Myanmar; his inability to respond emotionally to the tragedy was revealing, and because this was a podcast and not a TV interview she was able to patiently keep asking the question, rather than moving on to the next topic. Rebecca Reed: My name is Rebecca Reed and I’m an Education Consultant and Host of the Off the Assembly Line podcast. Off the Assembly Line is your weekly dose of possibility-sparking conversation with the educators and entrepreneurs bringing the future to education. My favorite episode was an interview with Julia Freeland Fisher, author of Who You Know. We talked about the power of student social capital, and the little known role it plays in the so-called “achievement gap” (or disparity in test scores from one school/district to the next). -

Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 Paul L. Robertson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons © Paul L. Robertson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robertson i © Paul L. Robertson 2019 All Rights Reserved. Robertson ii The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Paul Lester Robertson Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2000 Master of Arts in Appalachian Studies, Appalachian State University, 2004 Master of Arts in English, Appalachian State University, 2010 Director: David Golumbia Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2019 Robertson iii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank his loving wife A. Simms Toomey for her unwavering support, patience, and wisdom throughout this process. I would also like to thank the members of my committee: Dr. David Golumbia, Dr. -

S.C.R.A.M. Gazette

MARCH EDITION Chief of Police Dennis J. Mc Enerney 2017—Volume 4, Issue 3 S.c.r.a.m. gazette FBI, Sheriff's Office warn of scam artists who take aim at lonely hearts DOWNTOWN — The FBI is warning of and report that they have sent thousands of "romance scams" that can cost victims dollars to someone they met online,” Croon thousands of dollars for Valentine's Day said. “And [they] have never even met that weekend. person, thinking they were in a relationship with that person.” A romance scam typically starts on a dating or social media website, said FBI spokesman If you meet someone online and it seems "too Garrett Croon. A victim will talk to someone good to be true" and every effort you make to online for weeks or months and develop a meet that person fails, "watch out," Croon relationship with them, and the other per- Croon said. warned. Scammers might send photos from son sometimes even sends gifts like flowers. magazines and claim the photo is of them, say Victims can be bilked for hundreds or thou- they're in love with the victim or claim to be The victim and the other person are never sands of dollars this way, and Croon said the unable to meet because they're a U.S. citizen able to meet, with the scammer saying they most common victims are women who are 40 who is traveling or working out of the coun- live or work out of the country or canceling -60 years old who might be widowed, di- try, Croon said. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Tech That Reality Check Making Money from News

NEWS REALITY IN THE November 2018 CHECK Using technology to combat DIGITAL misinformation AGE CONTINENTAL SHIFT NBC News International’s Deborah Turness on covering a divided Europe MAKING MONEY FROM NEWS Industry leaders across TECH THAT Europe share their views Check out the smart tools reshaping reporting Paid Post by Google This content was produced by the advertising department of the Financial Times, in collaboration with Google. Paid Post by Google This content was produced by the advertising department of the Financial Times, in collaboration with Google. Digital News Innovation Fund 30 European countries 559 Projects €115M In funding g.co/newsinitiative 2 | GoogleNewsInitiative.ft.com Foreword THE FUTURE OF NEWS In 2015, Google launched the Digital News Innovation Fund (DNI Fund) to stimulate innovation across the European news industry. The DNI Fund supports ambitious projects in digital journalism across a range of areas – from creating open-source technology that improves revenue streams to investing in quality, data-driven investigative journalism. Ludovic Blecher Head of the Digital News Google asked a dozen leaders from the industry to allocate a total of Innovation Fund €150m to projects submitted by media companies and start-ups – no strings attached: all intellectual property remains with the companies themselves. To date, we’ve selected 559 projects across 30 countries, supporting them with more than €115m. But it’s not just about the money. The DNI Fund provides space and opportunity to take risks and experiment. In the media industry, many players don’t compete with each other across borders. We are Veit Dengler also proud to have fostered publishers working together to tackle Executive board member, their common challenges, through technological collaboration. -

Trumpism on College Campuses

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Trumpism on College Campuses Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1d51s5hk Journal QUALITATIVE SOCIOLOGY, 43(2) ISSN 0162-0436 Authors Kidder, Jeffrey L Binder, Amy J Publication Date 2020-06-01 DOI 10.1007/s11133-020-09446-z Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Qualitative Sociology (2020) 43:145–163 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-020-09446-z Trumpism on College Campuses Jeffrey L. Kidder1 & Amy J. Binder 2 Published online: 1 February 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract In this paper, we report data from interviews with members of conservative political clubs at four flagship public universities. First, we categorize these students into three analytically distinct orientations regarding Donald Trump and his presidency (or what we call Trumpism). There are principled rejecters, true believers, and satisficed partisans. We argue that Trumpism is a disunifying symbol in our respondents’ self- narratives. Specifically, right-leaning collegians use Trumpism to draw distinctions over the appropriate meaning of conservatism. Second, we show how political clubs sort and shape orientations to Trumpism. As such, our work reveals how student-led groups can play a significant role in making different political discourses available on campuses and shaping the types of activism pursued by club members—both of which have potentially serious implications for the content and character of American democracy moving forward. Keywords Americanpolitics.Conservatism.Culture.Highereducation.Identity.Organizations Introduction Donald Trump, first as a candidate and now as the president, has been an exceptionally divisive force in American politics, even among conservatives who typically vote Republican. -

FUNDING HATE How White Supremacists Raise Their Money

How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money 1 RESPONDING TO HATE FUNDING HATE INTRODUCTION 1 SELF-FUNDING 2 ORGANIZATIONAL FUNDING 3 CRIMINAL ACTIVITY 9 THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK: CROWDFUNDING 10 BITCOIN AND CRYPTOCURRENCIES 11 THE FUTURE OF WHITE SUPREMACIST FUNDING 14 2 RESPONDING TO HATE How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money It’s one of the most frequent questions the Anti-Defamation League gets asked: WHERE DO WHITE SUPREMACISTS GET THEIR MONEY? Implicit in this question is the assumption that white supremacists raise a substantial amount of money, an assumption fueled by rumors and speculation about white supremacist groups being funded by sources such as the Russian government, conservative foundations, or secretive wealthy backers. The reality is less sensational but still important. As American political and social movements go, the white supremacist movement is particularly poorly funded. Small in numbers and containing many adherents of little means, the white supremacist movement has a weak base for raising money compared to many other causes. Moreover, ostracized because of its extreme and hateful ideology, not to mention its connections to violence, the white supremacist movement does not have easy access to many common methods of raising and transmitting money. This lack of access to funds and funds transfers limits what white supremacists can do and achieve. However, the means by which the white supremacist movement does raise money are important to understand. Moreover, recent developments, particularly in crowdfunding, may have provided the white supremacist movement with more fundraising opportunities than it has seen in some time. This raises the disturbing possibility that some white supremacists may become better funded in the future than they have been in the past. -

Misinformation, Media Manipulation and Antisemitism an Annual Event at the Italian Academy Marking Holocaust Remembrance Day Looks at Online Extremism

Misinformation, Media Manipulation and Antisemitism An annual event at the Italian Academy marking Holocaust Remembrance Day looks at online extremism. By Abigail Asher February 17, 2020 A Facebook Case Costanza Sciubba Caniglia and Irene V. Pasquetto, both from the new Misinformation Review at the Harvard Kennedy School, took up the idea of combating online hate by “de-platforming” neo-Nazis. They cited an Italian case with unintended consequences: A violent, dangerous organization, the extreme-right, racist and antisemitic CasaPound lost its Facebook access in autumn 2019, but a civil court in Rome immediately judged that Facebook had violated the group’s free speech. Facebook reactivated CasaPound’s account and paid its legal costs. On February 5, 2020, researchers from a range of Asked to Remember, Not to Intervene disciplines spoke to a lively, full-capacity crowd at Rachel Deblinger, who works at UCLA and is co- the Italian Academy for this year’s Holocaust director of the Digital Jewish Studies Initiative at Remembrance Day symposium. The 2020 topic was University of California Santa Cruz, joined in (via online extremism, particularly the negation of historical Zoom) and discussed using social media to bring facts and the manipulation of social media to pursue Holocaust memories to life today, focusing on two neo-Nazi and neo-Fascist ideas. recent accounts: Twitter’s @Stl_Manifest (recalling the Nazi victims who were turned away by America in The Sensational and the Divisive 1939) and Instagram’s @eva.stories. Deblinger said that Alex Abdo, litigation director at the Knight First @eva.stories succeeds by spurring meaningful Amendment Institute, noted that social media interaction with the Holocaust, but it also fails by not companies’ “algorithmic amplification and suppression serving as a platform for documentation of today's global of speech appears to be deepening our political atrocities, as does Instagram. -

Reporting, and General Mentions Seem to Be in Decline

CYBER THREAT ANALYSIS Return to Normalcy: False Flags and the Decline of International Hacktivism By Insikt Group® CTA-2019-0821 CYBER THREAT ANALYSIS Groups with the trappings of hacktivism have recently dumped Russian and Iranian state security organization records online, although neither have proclaimed themselves to be hacktivists. In addition, hacktivism has taken a back seat in news reporting, and general mentions seem to be in decline. Insikt Group utilized the Recorded FutureⓇ Platform and reports of historical hacktivism events to analyze the shifting targets and players in the hacktivism space. The target audience of this research includes security practitioners whose enterprises may be targets for hacktivism. Executive Summary Hacktivism often brings to mind a loose collective of individuals globally that band together to achieve a common goal. However, Insikt Group research demonstrates that this is a misleading assumption; the hacktivist landscape has consistently included actors reacting to regional events, and has also involved states operating under the guise of hacktivism to achieve geopolitical goals. In the last 10 years, the number of large-scale, international hacking operations most commonly associated with hacktivism has risen astronomically, only to fall off just as dramatically after 2015 and 2016. This constitutes a return to normalcy, in which hacktivist groups are usually small sets of regional actors targeting specific organizations to protest regional events, or nation-state groups operating under the guise of hacktivism. Attack vectors used by hacktivist groups have remained largely consistent from 2010 to 2019, and tooling has assisted actors to conduct larger-scale attacks. However, company defenses have also become significantly better in the last decade, which has likely contributed to the decline in successful hacktivist operations. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

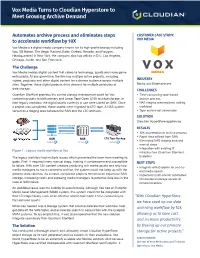

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals.