Hale Woodruff's Murals at Talladega College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hale Aspacio Woodruff 1900–1980)

Hale Aspacio Woodruff 1900–1980) Biography Hale Woodruff was a black artist who sought to express his heritage in his abstract painting. Of his artwork he said: "I think abstraction is just another kind of reality. And although you may see a realistic subject like a glass or a table or a chair, you have to transpose or transform that into a picture, and my whole feeling is that to get the spectator involved it has to extend that vision" . ." (Herskovic 358) Born in Cairo, Illinois, Woodruff grew up in Nashville, Tennessee. In the early 1920s, he studied at the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis, where he lived for a number of years. He later studied at Harvard University, the School of The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Académie Moderne and Académie Scandinave in Paris. He spent the summer of 1938 studying mural painting with Diego Rivera in Mexico, an experience that greatly affected Woodruff's evolving style until the early 1940s. Woodruff's earliest public recognition occurred in 1923 when one of his paintings was accepted in the annual Indiana artists' exhibition. In 1928 he entered a painting in the Harmon Foundation show and won an award of one hundred dollars. He bought a one-way ticket to Paris with the prize money, and managed to eke out four years of study with an additional donation from a patron. In 1931, Woodruff returned to the United States and began teaching art at Atlanta University. It was Woodruff who was responsible for that department's frequent designation as the École des Beaux Arts" of the black South in later years. -

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Mary Mcleod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Final General Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, D.C. Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement _____________________________________________________________________________ Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, District of Columbia The National Park Service is preparing a general management plan to clearly define a direction for resource preservation and visitor use at the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site for the next 10 to 15 years. A general management plan takes a long-range view and provides a framework for proactive decision making about visitor use, managing the natural and cultural resources at the site, developing the site, and addressing future opportunities and problems. This is the first NPS comprehensive management plan prepared f or the national historic site. As required, this general management plan presents to the public a range of alternatives for managing the site, including a preferred alternative; the management plan also analyzes and presents the resource and socioeconomic impacts or consequences of implementing each of those alternatives the “Environmental Consequences” section of this document. All alternatives propose new interpretive exhibits. Alternative 1, a “no-action” alternative, presents what would happen under a continuation of current management trends and provides a basis for comparing the other alternatives. Al t e r n a t i v e 2 , the preferred alternative, expands interpretation of the house and the life of Bethune, and the archives. It recommends the purchase and rehabilitation of an adjacent row house to provide space for orientation, restrooms, and offices. Moving visitor orientation to an adjacent building would provide additional visitor services while slightly decreasing the impacts of visitors on the historic structure. -

Modern Art Collection

MODERN ART COLLECTION Hale Aspacio Woodruff The Art of the Negro: Native Forms (study) 1950 Oil on canvas 23 × 21 in. (58.4 × 53.3 cm) Museum purchase, gift of an anonymous donor with additional funds provided by exchange, gift of Helen Sawyer Farnsworth 2005.17 A pioneering artist and educator, Hale Woodruff is best known for his mural series on the Amistad slave ship mutiny of 1839, executed for Talladega College in Alabama, and his Art of the Negro series at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University) in Georgia. Still in its original location in the rotunda of Clark Atlanta University’s Trevor Arnett Library, Woodruff’s Art of the Negro series comprises six canvases celebrating African art as a major influence on twentieth-century aesthetic production. Native Forms is a study for the first canvas in the series. Completed in 1939, the Amistad mural series in the Savery Library at Talladega College is painted in a regionalist style with naturalistic forms, strong outlines, and bold color, and owes much to the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, with whom Woodruff studied in 1936. The Art of the Negro series, on the other hand, shows Woodruff’s interest in European modernism and incorporates elements borrowed from cubism as well as references to African art. On the border between abstraction and figuration, the six compositions in the series respond to a shift in Woodruff’s style in the mid-1940s toward greater abstraction. Born in Cairo, Illinois, Woodruff studied at the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis, the Art Institute of Chicago, and Harvard University’s Fogg Museum School. -

2014 AAAM Conference Booklet

2014 Annual Conference Association of African American Museums HELP US BUILD THE MUSEUM h i P s A n e r s n d C r t o l P A l A B o r A t i o n s Birmingham, Alabama i August 6–9, 2014 n t RENEW your membership today. h e BECOME a member. DONATE. d The National Museum of African American History and i Culture will be a place where exhibitions and public g hosted by i programs inspire and educate generations to come. t Birmingham Civil rights institute A l Visit nmaahc.si.edu for more information. A g Program Design: Chris Danemayer, Proun Design, LLC. e Back Cover Front Cover THINGS HAVE CHANGED. SO HAVE WE. Association AAAM HISTORICAL OVERVIEW of African American Museums The African American Museum Movement emerged during the 1950s Board of Directors, 2013–2014 and 1960s to preserve the heritage of the Black experience and to ensure its Officers proper interpretation in American history. Black museums instilled a sense At the place of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Samuel W. Black of achievement within Black communities, while encouraging collaborations death in 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, the President National Civil Rights Museum was born. Pennsylvania between Black communities and the broader public. Most importantly, the African American Museums Movement inspired new contributions to society and Dr. Deborah L. Mack The Museum, a renowned educational Vice President advanced cultural awareness. Washington, D.C. and cultural institution that chronicles the In the late 1960s, Dr. Margaret Burroughs, founder of the DuSable Museum American Civil Rights Movement, has been Auntaneshia Staveloz Secretary in Chicago, and Dr. -

Executive Director Selected for Amistad Research Center

Tulane University Executive director selected for Amistad Research Center June 04, 2015 9:00 AM Alicia Duplessis Jasmin [email protected] Kara Tucina Olidge replaces Lee Hampton, who retired in June 2014, as head of the Amistad Research Center on the uptown campus of Tulane University. (Photo by Paula Burch-Celentano) In her new position as executive director of the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, Kara Tucina Olidge has outlined several goals for her first few years of tenure. The most ambitious of these goals is to double the center's endowment over a three- to five-year period. “This will allow us to focus on staff development and collections development,” says Olidge, who holds a doctorate in educational leadership and policy from State University of New York-Buffalo. “You have to think big, and you have to hit the ground running.” The center's current endowment is $2.25 million, and Olidge plans to use her previous experience in corporate development, grant writing and strategic planning to hit the $4.5 million goal by 2020. "We were impressed with how engaged she'd been with the community in previous positions. We're confident she'll do the same at Amistad." Tulane University | New Orleans | 504-865-5210 | [email protected] Tulane University Sybil Morial, board member, Amistad Research Center This experience is what made Olidge the standout candidate, says Sybil Morial, a 30-year Amistad board member and chair of the executive director search committee. “She knew about fiscal management and fund development,” says Morial of Olidge. “We were also impressed with how engaged she'd been with the community in previous positions. -

Complaint of Judicial Misconduct

Complaint of Judicial Misconduct Complainant arl Bernofsky The Hon. Ginger Berrigan. Ju 6478 General Diaz treet United tates District Court for the New Orleans LA 70124 Eastern District of Louisiana (504) 486-46"9 (504) 589-7515 I. Introduction The complainant was plaintiff in a serie of four lawsuits against Tulane Universit in which th Hon. Ginger Berrigan was Pr siding Judge. Relatively recent) , he learned that Judge Berrigan has had a material and continuing relationship with the defendant. Under Canon 3 of the ode of Judicial onduct, Judge Berrigan had a duty to disclose her as ociation with Tulane before sitting in any cas in which Tulane was a defendant. From Januar , 1995 onward Judge Berrigan continuously violated this Code in all of the complainant's lawsuits where she presided and failed to make any disclo ure. II. Statement of Facts A. Professorship Federal District ourt Judge Ginger Berrigan i Adjunct Associate Professor of Law at Tulane University and taught the cours Trial Advocacy during the 1995-96 academic year [1 2]. Since then, Judge Berrigan has maintained a professional association with Tulane through her continued participation in the Law School's Judicial Externship Program [3-5] and as a substitute instructor for the course, Federal Practice & Procedure: Trials [6], taught by the 76-year-old Adjunct Professor Federal District Court Judge Charles Schwartz Jr. [7]. B. Board Membership In 1990, Judge Berrigan then an attorney was appointed to the Board of Directors of Tulane University's Amistad Research Center, a position she occupied until 1997 [8]. 13 ERRIGAN.Q9C - I - The Amistad Research Center occupies a wing of Tilton Memorial Hall on the campus of Tulane University [9]. -

Aneta Pawłowska Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected]

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2014, vol. XVI ISSN 1641-9278 Aneta Pawłowska Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected] THE AMBIVALENCE OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN1 CULTURE. THE NEW NEGRO ART IN THE INTERWAR PERIOD Abstract: Reflecting on the issue of marginalization in art, it is difficult not to remember of the controversy which surrounds African-American Art. In the colonial period and during the formation of the American national identity this art was discarded along with the entire African cultural legacy and it has emerged as an important issue only at the dawn of the twentieth century, along with the European fashion for “Black Africa,” complemented by the fascination with jazz in the United States of America. The first time that African-American artists as a group became central to American visual art and literature was during what is now called the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s. Another name for the Harlem Renaissance was the New Negro Movement, adopting the term “New Negro”, coined in 1925 by Alain Leroy Locke. These terms conveyed the belief that African-Americans could now cast off their heritage of servitude and define for themselves what it meant to be an African- American. The Harlem Renaissance saw a veritable explosion of creative activity from the African-Americans in many fields, including art, literature, and philosophy. The leading black artists in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940 were Archibald Motley, Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, Hale Aspacio Woodruff, and James Van Der Zee. Keywords: African-American – “New Negro” – “Harlem Renaissance” – Photography – “African Art” – Murals – 20th century – Painting. -

Guide to Gwens Databases

THE LOUISIANA SLAVE DATABASE AND THE LOUISIANA FREE DATABASE: 1719-1820 1 By Gwendolyn Midlo Hall This is a description of and user's guide to these databases. Their usefulness in historical interpretation will be demonstrated in several forthcoming publications by the author including several articles in preparation and in press and in her book, The African Diaspora in the Americas: Regions, Ethnicities, and Cultures (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming 2000). These databases were created almost entirely from original, manuscript documents located in courthouses and historical archives throughout the State of Louisiana. The project lasted 15 years but was funded for only five of these years. Some records were entered from original manuscript documents housed in archives in France, in Spain, and in Cuba and at the University of Texas in Austin as well. Some were entered from published books and journals. Some of the Atlantic slave trade records were entered from the Harvard Dubois Center Atlantic Slave Trade Dataset. Information for a few records was supplied from unpublished research of other scholars. 2 Each record represents an individual slave who was described in these documents. Slaves were listed, and descriptions of them were recorded in documents in greater or lesser detail when an estate of a deceased person who owned at least one slave was inventoried, when slaves were bought and sold, when they were listed in a will or in a marriage contract, when they were mortgaged or seized for debt or because of the criminal activities of the master, when a runaway slave was reported missing, or when slaves, mainly recaptured runaways, testified in court. -

Via Issuelab

ROCKEFELLER ARCHIVE CENTER RESEARCH REPO RTS Whither the Rural? The Debate over Rural America’s Future, 1945-1980 by Doug Genens University of California, Santa Barbara © 2018 by Doug Genens Project Overview Following World War II, rural America experienced a number of interconnected transformations that raised the question of what its future might look like, or whether or not it even had one. My project examines the response of policymakers, rural people, and social scientists to the problems these changes created, which I am calling the “rural crisis.” More specifically, my dissertation examines how rural problems were understood by these groups, and the various ways they sought to build a new, more prosperous rural America and redefine the meaning of rural in the process. My research tracks the debates and implementation of public policies across distinct rural settings in California, Missouri, and Georgia. What exactly constituted the rural crisis following World War II? Foremost in the minds of many were major changes in American agriculture. Between 1900 and 1940, the size and number of farms in the United States remained relatively stable. Following the 1940s, however, the number of farms dropped from 5.9 million in 1945 to only 2.3 million in 1974. The average size of farms also doubled during this same period from just under 200 acres to over 400 acres. These larger farms became increasingly mechanized and captured a high proportion of the total farm product sales in the U.S.1 In part, scientific advances in seeds, fertilizers, and machines throughout the twentieth century allowed farmers to expand the size of their operations. -

Autumn 2014 Volume 29, Issue 1 Letter from the Senior Co-Chair

AACR Archivists and Archives of Color Roundtable Newsletter Autumn 2014 Volume 29, Issue 1 Letter from the Senior Co -Chair INSIDE THIS ISSUE Greetings Archivists and Archives of Color Roundtable Members, Welcome Letter 1 I am so honored to serve over the next year as chair of the roundtable. I am Pinkett Award Winner at SAA 2 looking forward to continuing the overall success the roundtable has achieved over the last 27 years. Member Spotlight 3, 4 Exhibitions 5 Over the next year, I hope to strengthen the roundtable by highlighting the ac- New Collections 6-8 complishments and activities of members through the inaugural “Member Accolades and Events 9 Spotlight” section which will be featured in every issue over the next year. The roundtable leadership will take a more targeted approach to engaging the Contest 10 membership on issues that matter most to you via Twitter and Facebook. The task forces will continue to research and write the history of the roundtable, participate in advocacy opportunities, and nominate AACR members and insti- tutions for awards through the Society of American Archivists. As I mentioned at the annual business meeting in Washington, I will be focusing on strategic planning and the first step will be to update the mission statement and to craft new vision and core values statements for the roundtable. A draft will be sent to the membership for comment and review in March, revised in May and adopted at the annual business meeting in Cleveland. I would like to welcome Aaisha Haykal (Chicago State University) as Junior Co- Chair, Amber Moore (Emory University) as the newsletter editor and Sonia Yaco (University of Illinois at Chicago) as webmaster to the roundtable leadership. -

African-American Documentary Resources on the World Wide Web: a Survey and Analysis

AFRICAN-AMERICAN DOCUMENTARY RESOURCES ON THE WORLD WIDE WEB: A SURVEY AND ANALYSIS BY ELAINE L. WESTBROOKS ABSTRACT: Numerous institutions have launched historical digital collections on the World Wide Web (WWW). This article describes, analyzes, and critiques 20 historical African-American digital collections created by archival institutions, academic insti- tutions, public libraries, and U.S. government agencies. In addition, it explores issues that are an important part of historical digital collections, such as preservation, integ- rity, and selection criteria, as well as trends in collection content, institutional policy, technology, Web-site organization, and remote reference. Finally, this article assesses the value of individual digital collections as well as the overall value of digitization. Introduction Currently, there is a scarcity of printed African-American documentary resources in the United States. There is also little information about archives, historical societies, museums, and repositories whose primary goal and purpose are to collect and organize these resources. This suggests that either African-American history is poorly docu- mented or that documented African-American history is not valuable to researchers. Neither is the case. African-American historical documents are available but not easily accessible. The trend to digitize' historical collections is making historical documents 2 more accessible; however, there is little research about digital collections of African- 3 archivists, and American history on the WWW. Though unnoticed by researchers, 4 librarians, dozens of institutions have digitized primary African-American documents. This paper addresses this information gap and will show how African-American his- torical documents are being made accessible to researchers. It will also explore the purpose of digitization. -

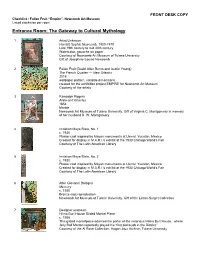

Checklist by Room

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I.