China Inc in India, 2000-2018: from State-Led to Market-Driven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

2020 (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) (Stock Code : 00656) Annual Report Profit Attributable to Owners of the Parent RMB 8,017.9 million Innovation & Win The year 2020 might be the most challenging year for Fosun, yet it was also the best year. After the pandemic, we continue with the “wartime mechanism” and maintain the fighting spirit that we have developed during the global combat against COVID-19. This has resulted in our resilient business performance throughout the year. The pandemic has also allowed us to refine further our capabilities of the Company accumulated over the years for “Industry Operations + Industrial Investment”, FC2M model, globalization and technology innovation. Fosun has thus evolved and become even stronger. The theme of Fosun’s annual report this year is “Innovation & Win”. “Innovation” means Fosun always attaches great importance to innovation. We recognize that we can create world-class products only by increasing investment in innovation and R&D. It is also because of our investment in technology innovation in various industries over the years, as well as leveraging on Fosun’s diversified and globalized business portfolio, the development model of “Industry Operations + Industrial Investment”, and the “wartime” mode that it has upkept since the battle against the pandemic, that together effectively defended the impact brought by the external environment and brought the Group a resilient performance, thereby creating mutually beneficial and win-win situation to all stakeholders. The year 2021 is a new starting point for Fosun’s transformation. Facing the huge opportunities in the industrial internet era, we will continue to create good products and put the operation of customers (C-end) as our top priority to fully unlock the multiplier growth of good products and customer resources in Fosun’s ecosystem. -

Biontech and Fosun Pharma Receive Authorization for Emergency Use in Hong Kong for COVID-19 Vaccine

BioNTech and Fosun Pharma Receive Authorization for Emergency Use in Hong Kong for COVID-19 Vaccine January 25, 2021 COMIRNATY® (also known as BNT162b2, Chinese product name: 復必泰TM) is the first COVID-19 vaccine to receive Authorization for Emergency Use in Hong Kong MAINZ, GERMANY, and SHANGHAI, CHINA, January 25, 2021 —BioNTech SE (Nasdaq: BNTX, “BioNTech” or “the Company”) and Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd. (“Fosun Pharma” or “Group”; Stock Code: 600196.SH, 02196.HK) today announced that according to the Food and Health Bureau of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the PRC (“Hong Kong”), the COVID-19 vaccine COMIRNATY® (also known as BNT162b2, Chinese product name: 復必泰TM) based on BioNTech’s proprietary mRNA technology has received authorization for emergency use in Hong Kong. The vaccine will be produced in BioNTech’s manufacturing facilities in Germany and supplied to Hong Kong for administration under the Hong Kong SAR Government’s COVID-19 Vaccination Program. “We are excited and encouraged that COMIRNATY® has been authorized to emergency use in Hong Kong. This is an important milestone in the joint efforts of BioNTech and Fosun Pharma to achieve vaccine accessibility globally. We will continue working closely with BioNTech to complete the ongoing clinical trial and marketing registration in Greater China,” Wu Yifang, Chairman and CEO of Fosun Pharma said. “We will also cooperate closely with HKSAR regarding vaccination deployment plan to ensure that Hong Kong citizens can receive a well-tolerated and effective mRNA COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible in order to protect the health of millions of households.” On 16 March 2020, BioNTech and Fosun Pharma announced a strategic collaboration to work jointly on the development and commercialization of a COVID-19 vaccine product in Greater China based on BioNTech’s proprietary mRNA technology platform. -

ACAL China Equity Nov17

ARETE CAPITAL ASIA CHINA: VALUE IN SELECTED NAMES CHINA EQUITY – OVERVIEW CHINA IS TAKING ITS PLACE ON THE WORLD STAGE • China is a critical player in the world economy and is the worlds largest economy on a purchasing power parity basis. • Xi’s position has been reinforced for the next 5yrs and possibly beyond. The new leadership will retain existing key policies with a focus on economic reform and an emphasis on foreign policy. ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION WELL UNDERWAY • ‘Smokestack’ industries (coal, aluminium and steel) and ‘providing for populace’ businesses (consumer staples and healthcare) are no longer so dominant and being overtaken by manufacturers and service companies. • In many cases, these new ‘service’ industries are redefining business models in established sectors • The China government has selected and carefully encouraged special policies/industries to have Chinese operations challenge the established order – internally and externally INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES EXIST • Amongst the many transformations taking place in China, there are numerous great investment opportunities. We do not recommend an index, but selected stocks • Some of these stocks have made significant gains over the last 12months, but there is still more to come 2 CONTENT OVERVIEW ECONOMY Economy Issues Diversification 4 5 6 Equities Remninbi VALUATIONS 7 8 SITUATIONS MiddlePORTFOLIO Class ecosystem ADVISORY 9 10 SELECTED STOCKS Preferred 11 Valuations 13 3 CHINA – ECONOMY CHINA’s ECONOMIC GROWTH REMAINS RESILIENT … • IMF forecasts (not a leading indicator) -

Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results

14 August 2020 Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results Hang Seng Indexes Company Limited (“Hang Seng Indexes”) today announced the results of its review of the Hang Seng Family of Indexes for the quarter ended 30 June 2020. All changes will take effect on 7 September 2020 (Monday). 1. Hang Seng Index The following constituent changes will be made to the Hang Seng Index. The total number of constituents remains unchanged at 50. Inclusion: Code Company 1810 Xiaomi Corporation - W 2269 WuXi Biologics (Cayman) Inc. 9988 Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. - SW Removal: Code Company 83 Sino Land Co. Ltd. 151 Want Want China Holdings Ltd. 1088 China Shenhua Energy Co. Ltd. - H Shares The list of constituents is provided in Appendix 1. The Hang Seng Index Advisory Committee today reviewed the fast expanding innovation and new economy sectors in the Hong Kong capital market and agreed with the proposal from Hang Seng Indexes to conduct a comprehensive study on the composition of the Hang Seng Index. This holistic review will encompass various aspects including, but not limited to, composition and selection of constituents, number of constituents, weightings, and industry and geographical representation, etc. The underlying aim of the study is to ensure the Hang Seng Index continues to serve as the most representative and important benchmark of the Hong Kong stock market. Hang Seng Indexes will report its findings and propose recommendations to the Advisory Committee within six months. The number of constituents of the Hang Seng Index may increase during this period. Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results /2 2. -

China Pharmaceuticals China Pharmaceuticals Spring Is in the Air – We Expect a Year of Healthy Growth

EQUITIES HEALTHCARE March 2017 By: Zhijie Zhao https://www.research.hsbc.com China Pharmaceuticals China China Pharmaceuticals Spring is in the air – we expect a year of healthy growth The policy pain of 2016 starts to ease and the industry’s fundamentals remain robust Multinational companies are reducing their focus on off-patent drugs in China, opening up a range Equities // Healthcare // Equities of opportunities We raise our target prices between 11% and 25%; we prefer Hengrui, Sino Biopharm and CMS, all rated Buy March 2017 March Disclaimer & Disclosures: This report must be read with the disclosures and the analyst certifications in the Disclosure appendix, and with the Disclaimer, which forms part of it EQUITIES ● HEALTHCARE March 2017 THIS CONTENT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED TO THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (THE "PRC") (EXCLUDING SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGIONS OF HONG KONG AND MACAO) The dark clouds are lifting The pain is easing as the risks associated with industry reforms recede We forecast that the net profit growth of our covered companies will average 19% in 2017e and 23% in 2018e, up from 18% in 2016e We raise our target prices by 11-25%; we prefer Hengrui, Sino Biopharm and CMS, all rated Buy Last year we wrote that China’s attempts to improve the healthcare system were proving painful for pharma companies (China Pharmaceuticals – 2016: Painful symptoms, possible remedies, 1 March 2016). We said that, although efforts to cut the cost of healthcare and improve industry standards would make the first half of 2016 difficult, we remained strong believers in China’s pharma story. -

股 份 有 限 公 司 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult a stockbroker or other registered dealer in securities, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.*, you should at once hand this circular, together with the enclosed form of proxy, to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s) or to the bank, stockbroker or other agents through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s). Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. 上 海 復 星 醫 藥( 集 團 )股 份 有 限 公 司 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 02196) REPORT ON THE USE OF PROCEEDS PREVIOUSLY RAISED AND NOTICE OF EGM A letter from the Board is set out on pages 3 to 5 of this circular. The notice convening the EGM of Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* to be held at 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday, 14 July 2021 at Shanghai Film Art Center, No. -

Annual Report 2020 03 Corporate Information

Our Vision Dedicate to become a first-tier enterprise in the global mainstream pharmaceutical and healthcare market. Our Mission Better health for families worldwide. 02 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd. Contents 04 Corporate Information 07 Financial Highlights 08 Chairman’s Statement 12 Management Discussion and Analysis 67 Five-Year Statistics 68 Report of the Directors 91 Supervisory Committee Report 93 Corporate Governance Report 104 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 135 Biographical Details of Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 144 Independent Auditor’s Report 149 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss 150 Consolidated Income Statement 151 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 153 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 155 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 157 Notes to Financial Statements 276 Definitions Annual Report 2020 03 Corporate Information Directors Authorized Representatives Executive Director Mr. Wu Yifang (吳以芳)11 Mr. Wu Yifang (吳以芳) Ms. Kam Mei Ha Wendy (甘美霞) (Chairman1 and Chief Executive Officer) Mr. Chen Qiyu (陳啟宇)12 Non-executive Directors Strategic Committee Mr. Chen Qiyu (陳啟宇)2 Mr. Chen Qiyu (陳啟宇) (Chairman) Mr. Yao Fang (姚方)3 Mr. Wu Yifang (吳以芳) Mr. Xu Xiaoliang (徐曉亮) Mr. Yao Fang (姚方) Mr. Gong Ping (龔平)4 Mr. Xu Xiaoliang (徐曉亮) Mr. Pan Donghui (潘東輝)4 Ms. Li Ling (李玲) Mr. Zhang Houlin (張厚林)5 Mr. Liang Jianfeng (梁劍峰)6 Audit Committee Mr. Wang Can (王燦)7 Ms. Mu Haining (沐海寧)9 Mr. Tang Guliang (湯谷良) (Chairman) Mr. Jiang Xian (江憲) Independent Non-executive Directors Mr. Gong Ping (龔平)4 Mr. Jiang Xian (江憲) Mr. Wang Can (王燦)7 Dr. Wong Tin Yau Kelvin (黃天祐) Ms. -

Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results of Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index Series

12 August 2016 HANG SENG INDEXES ANNOUNCES INDEX REVIEW RESULTS OF HANG SENG CORPORATE SUSTAINABILITY INDEX SERIES Hang Seng Indexes Company Limited (“Hang Seng Indexes”) today announced the results of its annual review of the Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index Series (“Index Series”) for 2016. All changes will be effective on 5 September 2016 (Monday). Shangri-La Asia Ltd (HKEX Stock Code: 69) will be added to the Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index (“HSSUS”). Orient Overseas (International) Ltd. (HKEX Stock Code: 316) will be deleted from the HSSUS since the company no longer meets the market capitalisation requirement. The constituent changes and the constituent lists of the five indexes in the Index Series are provided in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 respectively. The constituent selection of the Index Series includes consideration of the results of the HKQAA Sustainability Rating and Research sustainability assessment, developed and carried out by the Hong Kong Quality Assurance Agency (“HKQAA”), in which the sustainability performance score is measured against the seven core subjects. The HKQAA was appointed by Hang Seng Indexes as its project partner for the Index Series starting from 2014. The three highest-scoring sustainability performers across the Index Series, shown in ascending stock code order, are Hang Seng Bank Ltd. (HKEX Stock Code: 11), Sino Land Co. Ltd. (HKEX Stock Code: 83) and Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd. (HKEX Stock Code: 388). more… HANG SENG INDEXES ANNOUNCES INDEX REVIEW RESULTS OF HANG SENG CORPORATE SUSTAINABILITY INDEX SERIES/2 Constituent companies with the highest scores in each of the core subjects across the Index Series are listed below: Core Subjects Company Name (HKEX Stock Code) Community Involvement and HSBC Holdings plc (0005) Development Consumer Issues Orient Overseas (International) Ltd. -

上海復星醫藥(集團)股份有限公司 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 上 海 復 星 醫 藥( 集 團 )股 份 有 限 公 司 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 02196) OVERSEAS REGULATORY ANNOUNCEMENT This announcement is made pursuant to Rule 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. The following sets out the ‘‘Announcement in Relation to the Signing of License Agreement and Investment Binding Term Sheet by Subsidiaries’’ published by Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* (the ‘‘Company’’) on the website of the Shanghai Stock Exchange, for your reference only. The following is a translation of the abovementioned announcement solely for the purpose of providing information. Should there be any discrepancies, the Chinese version will prevail. By order of the Board Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* Chen Qiyu Chairman Shanghai, the People’s Republic of China 15 March 2020 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are Mr. Chen Qiyu, Mr. Yao Fang and Mr. Wu Yifang; the non-executive directors of the Company are Mr. Xu Xiaoliang and Ms. Mu Haining; and the independent non- executive directors of the Company are Mr. -

China Healthcare

KURE 9/30/2019 China Healthcare: Potential Opportunities From One Of The Fastest Growing Major Global Healthcare Markets1 An Overview of the KraneShares MSCI All China Health Care Index ETF (Ticker: KURE) 1. Major healthcare markets defined as top five global markets by the World Health Organization. Data from the World Health Organization as of 12/31/2016, last updated on 1/8/2019, retrieved on 9/30/2019. [email protected] 1 Introduction to KraneShares About KraneShares Krane Funds Advisors, LLC is the investment manager for KraneShares ETFs. Our suite of China focused ETFs provides investors with solutions to capture China’s importance as an essential element of a well-designed investment portfolio. We strive to provide innovative, first to market strategies that have been developed based on our strong partnerships and our deep knowledge of investing. We help investors stay up to date on global market trends and aim to provide meaningful diversification. Krane Funds Advisors, LLC is majority owned by China International Capital Corporation (CICC). 2 Investment Strategy: KURE seeks to measure the performance of MSCI China All Shares Health Care 10/40 Index. The Index is a free float adjusted market capitalization weighted index designed to track the equity market performance of Chinese companies engaged in the health care sector. The securities in the Index include all types of publicly issued shares of Chinese issuers, which are listed in Mainland China, Hong Kong and the KURE United States. Issuers eligible for inclusion must be classified under the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) as engaged in the healthcare sector. -

上海復星醫藥(集團)股份有限公司 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 上海復星醫藥(集團)股份有限公司 Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 02196) OVERSEAS REGULATORY ANNOUNCEMENT This announcement is made pursuant to Rule 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. The following sets out the “Announcement in Relation to Receipt of Approval for Drug Clinical Trial by a Subsidiary” published by Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) on the website of the Shanghai Stock Exchange, for your reference only. The following is a translation of the abovementioned announcement solely for the purpose of providing information. Should there be any discrepancies, the Chinese version will prevail. By order of the Board Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd.* Chen Qiyu Chairman Shanghai, the People’s Republic of China 28 June 2020 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are Mr. Chen Qiyu, Mr. Yao Fang and Mr. Wu Yifang; the non-executive directors of the Company are Mr. Xu Xiaoliang and Ms. Mu Haining; and the independent nonexecutive directors of the Company are Mr. Jiang Xian, Dr. Wong Tin Yau Kelvin, Ms. -

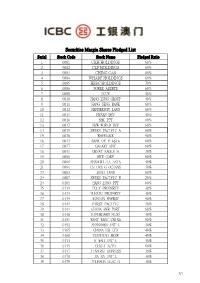

Securities Margin Shares Pledged List

Securities Margin Shares Pledged List Serial Stock Code Stock Name Pledged Ratio 1 0001 CKH HOLDINGS 60% 2 0002 CLP HOLDINGS 60% 3 0003 CHING GAS 60% 4 0004 WHARF HOLDINGS 60% 5 0005 HSBC HOLDINGS 70% 6 0006 POWER ASSETS 60% 7 0008 PCCW 40% 8 0010 HANG LUNG GROUP 40% 9 0011 HANG SENG BANK 60% 10 0012 HENDERSON LAND 60% 11 0014 HYSAN DEV 40% 12 0016 SHK PPT 60% 13 0017 NEW WORLD DEV 60% 14 0019 SWIRE PACIFIC A 60% 15 0020 WHEELOCK 50% 16 0023 BANK OF E ASIA 60% 17 0027 GALAXY ENT 60% 18 0041 GREAT EAGLE H 30% 19 0066 MTR CORP 60% 20 0069 SHANGRI-LA ASIA 40% 21 0081 CH OVS G OCEANS 30% 22 0083 SINO LAND 60% 23 0087 SWIRE PACIFIC B 20% 24 0101 HANG LUNG PPT 60% 25 0119 POLY PROPERTY 30% 26 0123 YUEXIU PROPERTY 40% 27 0135 KUNLUN ENERGY 50% 28 0142 FIRST PACIFIC 30% 29 0144 CHINA MER PORT 60% 30 0148 KINGBOARD HLDG 40% 31 0151 WANT WANT CHINA 50% 32 0152 SHENZHEN INT'L 30% 33 0165 CHINA EB LTD 40% 34 0168 TSINGTAO BREW 40% 35 0173 K WAH INT'L 30% 36 0175 GEELY AUTO 60% 37 0177 JIANGSU EXPRESS 30% 38 0178 SA SA INT'L 30% 39 0179 JOHNSON ELEC H 30% 1/7 Serial Stock Code Stock Name Pledged Ratio 40 0200 MELCO INT'L DEV 30% 41 0215 HUTCHTEL HK 20% 42 0220 U-PRESID CHINA 40% 43 0242 SHUN TAK HOLD 30% 44 0257 CHINA EB INT'L 40% 45 0267 CITIC 60% 46 0268 KINGDEE INT'L 20% 47 0270 GUANGDONG INV 40% 48 0272 SHUI ON LAND 30% 49 0285 BYD ELECTRONIC 30% 50 0288 WH GROUP 60% 51 0291 CHINA RES BEER 40% 52 0293 CATHAY PAC AIR 50% 53 0303 VTECH HOLDINGS 30% 54 0308 CHINA TRAVEL HK 30% 55 0315 SMARTONE TELE 20% 56 0322 TINGYI 50% 57 0323 MAANSHAN IRON 20%