Incidence of Blackleg in Beef Cattle and Implications of Regional Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheep Diseases the FARMERS’ GUIDE 2Nd Edition - July 2015 Sheep Diseases the FARMERS’ GUIDE

Sheep Diseases THE FARMERS’ GUIDE 2nd Edition - July 2015 Sheep Diseases THE FARMERS’ GUIDE Developed by: Emily Litzow for Primary Industries and Regions South Australia, Biosecurity SA Animal Health Funded by: SA Sheep Industry Fund and Biosecurity SA Use of the information/advice in this guide is at your own risk. The Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The entire risk of the implementation of the information/ advice which has been provided to you is assumed by you. All liability or responsibility to any person using the information/advice is expressly disclaimed by the Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA and its employees. 2 Acknowledgements and Further Reading The Information in this publication has been collected from: Allan, S 2010, Foot Abscess in Sheep, NSW DPI Primefact 7, NSW. Animal Biosecurity Unit 2008, Ovine Johne’s Disease, NSW DPI Primefact 661, NSW. Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines - Land Transport of Livestock, Animal Health Australia (AHA) 2012, Canberra. Brightling, A 2006, Livestock Diseases in Australia, C H Jerram and Associates Science Publishers, Australia. Butler, R 2008, Ovine Brucellosis, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 334, WA. Chester, L 2010, Sheep Welfare – Avoiding Losses due to Hypothermia, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 453, WA. Cotter, J 2011, Sheep Lice – Spread and Detection, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 478, WA. Erickson, A 2010, Hydatid Disease, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 448, WA. -

Blackleg and Clostridial Diseases

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION UJA--University of Arkansas System Agriculture and atural Resources FSA3073 Livestock Health eries Blackleg and Other Clostridial Diseases symptoms. Therefore, prevention of Heidi Ward, Introduction these diseases through immunization VM, Ph Clostridial bacteria cause several is more successful than trying to treat Assistant Professor diseases that affect cattle and other infected animals. and Veterinarian farm animals. This group of bacteria is known to produce toxins with varying effects based on the way they enter the Blackleg Jeremy Powell, body. The bacteria are frequently Blackleg, or clostridial myositis, VM, Ph found in the environment (primarily in affects cattle worldwide and is caused Professor the soil) and tend to multiply in warm by Clostridium chauvoei. Susceptible weather following heavy rain. The animals first ingest endospores. The bacteria are also found in the intes - endospores then cross over the gastro - tinal tracts of healthy farm animals, intestinal tract and enter the blood- where they only cause disease under stream where they are deposited in certain circumstances. The most muscle tissue in the animal’s body. common diseases caused by clostridial They then lie dormant in the tissue bacteria in beef cattle are blackleg, until they become activated and enterotoxemia, malignant edema, black trigger the disease. disease and tetanus. These diseases Clostridium chauvoei is activated are usually seen in young cattle (less in an anaerobic (oxygen deficient) than 2 years of age) and are widely environment such as damaged, distributed throughout Arkansas. devitalized or bruised tissue. Events Bacteria of the Clostridium genus such as transport, rough handling or produce long-lived structures called aggressive pasture activity can lead to endospores. -

Studies Upon the Blackleg Disease of the Potato, with Special Reference to the Rela- Tionship of the Causal Organisms

STUDIES UPON THE BLACKLEG DISEASE OF THE POTATO, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE RELA- TIONSHIP OF THE CAUSAL ORGANISMS By W. J. MORSE, Plant Pathologist, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station HISTORICAL REVIEW The fact that the potato (Solanum tuberosum) is subject to maladies like that under consideration in this paper was noted at a comparatively early date in the literature of bacterial diseases of plants. De Jubain- ville and Vesque (8)1 mentioned in 1878 a "cellular-rot" of potatoes, radishes, carrots, and beets as occurring in the soil and in cellars; but bacteria are not mentioned as the cause. Their paper and the one following are reviewed by Smith (32). In 1879 Reinke and Berthold (30) pointed out quite clearly that a wetrot of potatoes could occur without the presence of any fungi. According to Smith, they apparently did not have any active parasite and did not work with pure cultures. However, they were able to inoculate and cause a decay of healthy tubers by means of the watery fluid taken from diseased potatoes, provided especially favorable condi- tions were supplied in the line of moisture. They were also able to demonstrate the constant association of bacteria with the wetrotting of the tubers. Prillieux and Delacroix (28) described a disease of the potato stem from France in 1890 and gave the name "Bacillus caulivorus" to the organism which they considered to be the cause. Nothing is said in this paper as to the isolation of the organism and the growth of it in pure cultures, although later Prillieux (27, v. -

Blackleg in Cattle: Current Understanding and Future Research Needs

Ciência Rural, Santa Maria, v.48:05,Blackleg e20170939,in cattle: current 2018 understanding and future research http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20170939 needs. 1 ISSNe 1678-4596 MICROBIOLOGY Blackleg in cattle: current understanding and future research needs Rosangela Estel Ziech1* Leticia Trevisan Gressler2 Joachim Frey3 Agueda Castagna de Vargas1 1Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), 97105-900, Santa Maria, RS, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected]. *Corresponding author. 2Instituto Federal Farroupilha (IFFar), Frederico Westphalen, RS, Brasil. 3Institute of Veterinary Bacteriology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. ABSTRACT: Blackleg is an endogenous acute infection that principally affects cattle, whose etiologic agent is the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium chauvoei. In recent years, the major virulence factors of C. chauvoei have been discovered and described. However, the pathogenesis of blackleg in cattle, and in particular, the movement of the pathogen from the point of entry to the affected tissues is not yet fully elucidated. Disease control is based on appropriate management and vaccination. This review summarizes the latest research findings that contribute toward the understanding of the disease in cattle, provide a foundation to preventive strategies, and identify future research needs. Key words: Clostridium chauvoei, sudden death, myonecrosis. Carbúnculo sintomático: compreensão atual e futuras necessidades de pesquisa RESUMO: O carbúnculo sintomático é uma infecção endógena, aguda, que acomete principalmente bovinos, cujo agente etiológico é a bactéria anaeróbica Clostridium chauvoei. Recentemente, os principais fatores de virulência do C. chauvoei foram descobertos e descritos. Contudo, a patogênese do carbúnculo sintomático em bovinos, especialmente a circulação do patógeno desde o ponto de entrada até os tecidos acometidos ainda não está completamente elucidada. -

Blackleg ( Clostridium Chauvoei Infection) in Beef Calves: a Review and Presentation of Two Cases with Uncommon Pathologic Presentations

PEER REVIEWED Blackleg ( Clostridium chauvoei Infection) in Beef Calves: A Review and Presentation of Two Cases with Uncommon Pathologic Presentations 1 2 Russell F. Daly ·, DVM; Dale W. Miskimins1, DVM, MS; Roland G. Good , DVM; Thomas Stenberg', DVM 1Veterinary Science Department, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD 57007 2Parker Veterinary Clinic, Parker, SD 57053-5661 3Volga Veterinary Clinic, Volga, SD 57071-2006 *Corresponding author: Russ Daly, 605-688-6589 Office, [email protected] Abstract laires sont bien connues et incluent des changements sous cutanes gelatineux et gazeux de meme que des Blackleg (Clostridium chauvoei infection) has long necroses musculaires bien demarquees. Des zones de been recognized as a cause of death in calves grazing necrose peuvent aussi etre presentes dans le myocarde, summer pastures. Clinical signs are not often observed le diaphragme et la langue par exemple. Les lesions in affected calves due to the peracute nature of the macroscopiques primaires chez les animaux examines disease, but may include fever, lameness, and swelling etaient associees a des pleuresies et a des pericardites. and crepitation over large muscle groups, followed by Des lesions de charbon symptomatique plus typiques se collapse and death. Typical gross and histopathologic retrouvaient chez certains mais pas chez tous les veaux lesions in these muscle groups are well-described and atteints et incluaient une necrose dans les muscles de include gelatinous, gassy subcutaneous changes, along la cuisse et de l'abdomen, une decoloration foncee du with well-defined muscle necrosis. Areas of necrosis can muscle du diaphragme et des indices histologiques de also be present in myocardium, diaphragm, and tongue, myocardite necrotique. -

Blackleg Barry Whitworth, DVM Area Food/Animal Quality and Health

Blackleg Barry Whitworth, DVM Area Food/Animal Quality and Health Specialist for Eastern Oklahoma Usually at least one time each summer that I was in practice, a producer would call to inform me of the sudden death of his or her best calf. After more conversation and examining the dead animal, a diagnosis of blackleg would usually be made to the surprise of the producer. Blackleg is caused by a rod shaped bacteria called Clostridium chauvoei. This bacteria causes an acute non-contagious but highly fatal disease of the heart and skeletal muscle. The bacteria is found worldwide. It exist in the environment in spores. The spores gain entry to the body by ingestion or by contamination of an open wound. If ingested the bacteria lie dormant in the liver, spleen, and gastrointestinal tract. The bacteria gains access to the muscle tissue following an injury or bruising. The damaged tissue is ideal for the pathogen to proliferate and produce toxins. The toxins cause muscle death. Weather may play a role in disease outbreaks. An increase in the number of cases may follow flooding conditions. Floods disturb the soil exposing the spores. During droughts, cases may increase due to grazing closer to the soil. Grazing so low increases the likelihood of coming in contact with the spores. In most cases of blackleg, the onset of the disease occurs between 6 months and 2 years of age. Rarely do animals over 2 years of age get the disease. Clinical signs of the disease are rarely seen. Most animals will be found dead. -

Upcoming Events Word from Your Ag Agent

11475-A FM 1442 Orange, TX 77630 Phone: 409-882-7010 Fax: 409-745-9889 January-February-March 2017 Upcoming Events Word from your Ag Agent Upcoming Programs Please RSVP Howdy, Orange County! We have certainly kicked off the year with th April 18 : Ag Symposium a bang! We have many programs and events going on, and plenty April 20th: Healthy Soil and Healthy of CEU opportunities this quarter. Thank you all for coming to our Lawn, 6pm, 2 CEU General programs, and if there is any area you feel you need knowledge on May 5 & 6: Earth–Kind Specialist let us know. Training, Cost is $100.00 May 8th: Native Plants 6pm $12.00 I first want to thank all of you for helping us get supplies and other May 13th: Rainwater Harvest, Volunteers donations to the Panhandle Fire Victims. I promise we will keep you needed, and spots open, 9:30 – Noon updated if they need anything, but at this time our efforts have $50.00 ceased. It truly is a blessing that I serve a county that cares so much May 23rd: Weed ID and Pasture Man- for others and that you guys are so willing to help out in any way agement, Barron Rector, 2 CEUs, 6pm, possible those that are in need. $12.00 June 1st: Succulents, 6pm, $10.00 Lastly, guys I have many programs coming up—a 5 Hour CEU event June 6th: Pond Management, 6pm and a training June 24th! Take a look through here and you should see many topics and programs from Pecans to Ponds and every- June 24th: 5 Hour CEU Program—Save the DATE thing in between. -

Hygiene Aspects of the Biogas Process with Emphasis on Spore-Forming Bacteria

Hygiene Aspects of the Biogas Process with Emphasis on Spore-Forming Bacteria Elisabeth Bagge Department of Bacteriology, National Veterinary Institute and Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences Department of Biomedical Sciences and Veterinary Public Health Uppsala Doctoral Thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2009 Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae 2009:28 Cover: Västerås biogas plant (photo: E. Bagge, November 2006) ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN 978-91-86195-75-5 © 2009 Elisabeth Bagge, Uppsala Print: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2009 Hygiene Aspects of the Biogas Process with Emphasis on Spore-Forming Bacteria Abstract Biogas is a renewable source of energy which can be obtained from processing of biowaste. The digested residues can be used as fertiliser. Biowaste intended for biogas production contains pathogenic micro-organisms. A pre-pasteurisation step at 70°C for 60 min before anaerobic digestion reduces non spore-forming bacteria such as Salmonella spp. To maintain the standard of the digested residues it must be handled in a strictly hygienic manner to avoid recontamination and re-growth of bacteria. The risk of contamination is particularly high when digested residues are transported in the same vehicles as the raw material. However, heat treatment at 70°C for 60 min will not reduce spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus spp. and Clostridium spp. Spore-forming bacteria, including those that cause serious diseases, can be present in substrate intended for biogas production. The number of species and the quantity of Bacillus spp. and Clostridium spp. in manure, slaughterhouse waste and in samples from different stages during the biogas process were investigated. -

Blackleg and Clostridial Diseases

BCM – 31 Blackleg and Clostridial Diseases The Clostridial diseases are a group of mostly Malignant Edema fatal infections caused by bacteria belonging to Malignant edema is a disease of cattle of any age the group called Clostridia. These organisms caused by CI. septicum is found in the feces of have the ability to form protective shell-like forms most domestic animals and in large numbers in called spores when exposed to adverse the soil where livestock populations are high. The conditions. This allows them to remain potentially organism gains entrance to the body in deep infective in soils for long periods of time and wounds and can even be introduced into deep present a real danger to the livestock population. vaginal or uterine wounds in cows following Many of the organisms in this group are also difficult calving. The symptoms are those normally present in the intestines of man and primarily of depression, loss of appetite and a wet animals. doughy swelling around the wound which often gravitates to lower portions of the body. Black Leg Temperatures of 106° or more are associated Blackleg is a disease caused by Clostridium with the infection with death frequently occurring chauvoei and primarily affects cattle under two in twenty-four to forty-eight hours. years of age and is usually seen in the better doing calves. The organism is taken in by mouth. Post mortem lesions seen are those of necrotic, Symptoms first noted are those of lameness and darkened foul smelling areas under the skin, depression. A swelling caused by gas bubbles, often extending into muscle. -

Clostridial Diseases of Cattle

Clostridial Diseases of Cattle Item Type text; Book Authors Wright, Ashley D. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Download date 01/10/2021 18:20:24 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625416 AZ1712 September 2016 Clostridial Diseases of Cattle Ashley Wright Vaccinating for clostridial diseases is an important part of a ranch health program. These infections can have significant Sporulating bacteria, such as Clostridia and Bacillus, economic impacts on the ranch due to animal losses. There form endospores that protect bacterial DNA from extreme are several diseases caused by different organisms from the conditions such as heat, cold, dry, UV radiation, and some genus Clostridia, and most of these are preventable with a disinfectants. Unlike fungal spores, these spores cannot sound vaccination program. Many of these infections can proliferate; they are dormant forms of the bacteria that allow progress very rapidly; animals that were healthy yesterday survival until environmental conditions are ideal for growth. are simply found dead with no observed signs of sickness. In most cases treatment is difficult or impossible, therefore we absence of oxygen to survive. Clostridia are one genus of rely on vaccination to prevent infection. The most common bacteria that have the unique ability to sporulate, forming organisms included in a 7-way or 8-way clostridial vaccine microscopic endospores when conditions for growth and are discussed below. By understanding how these diseases survival are less than ideal. Once clostridial spores reach a occur, how quickly they can progress, and which animals are suitable, oxygen free, environment for growth they activate at risk you will have a chance to improve your herd health and return to their bacterial (vegetative) state. -

Blackleg Vaccines: Their Production and Use Summary

BLACKLEG VACCINES: THEIR PRODUCTION AND USE SUMMARY. 1. Blackleg is an acute disease of young cattle having such a short duration that curative measures should not be relied on. 2. Preventive treatment by early injection of blackleg filtrate or aggressin is highly important. 3. Preventive treatment should be given before losses occur, as the saving of one calf will pay for a large number of doses. 4. The treatment should be administered before changes are made to a more nourishing diet. 5. The immunity produced by the use of blackleg filtrate or ag- gressin does not develop for three to ten days after its injection, but after this immunity is produced it is of long duration. 6. Should losses occur before treatment is possible it is advisable to give all cattle antiblackleg serum, following this in 10 to 12 days with a dose of filtrate or aggressin. 7. The use of antiblackleg serum will stop all losses within 24 hours, but the protection produced will last only from ten days to three weeks. 8. The early treatment of all calves with blackleg filtrate or ag- gressin gives good assurance that there will be no losses from black- leg. 9. Vaccination by means of powder vaccines is unsatisfactory in certain respects. 10. The immunity produced by aggressin or filtrate is of a very high degree, both products having practically the same immunizing powers. 11. The absolute length of the immunity produced by aggressin or filtrate is as yet undetermined; however, field work covering over four years shows that an animal vaccinated when six months of age is usually protected until it is no longer susceptible to blackleg. -

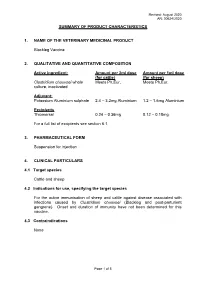

Summary of Product Characteristics 1. Name Of

Revised: August 2020 AN: 00624/2020 SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCT Blackleg Vaccine 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Active ingredient: Amount per 2ml dose Amount per 1ml dose (for cattle) (for sheep) Clostridium chauvoei whole Meets Ph.Eur. Meets Ph.Eur. culture, inactivated Adjuvant: Potassium Aluminium sulphate 2.4 – 3.2mg Aluminium 1.2 – 1.6mg Aluminium Excipients Thiomersal 0.24 – 0.36mg 0.12 – 0.18mg For a full list of excipients see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Suspension for injection 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Target species Cattle and sheep 4.2 Indications for use, specifying the target species For the active immunisation of sheep and cattle against disease associated with infections caused by Clostridium chauvoei (Blackleg and post-parturient gangrene). Onset and duration of immunity have not been determined for this vaccine. 4.3 Contraindications None Page 1 of 5 Revised: August 2020 AN: 00624/2020 4.4 Special warnings for each target species Clinical trials have demonstrated that the presence of maternal antibodies against C. chauvoei may reduce the antibody response to vaccination in young lambs. Therefore, to ensure an optimal response in young animals with high levels of MDA, the primary vaccination should be delayed until the levels wane (which is after about 8-12 weeks of age). In any animal population, there may be a number of individuals which fail to respond fully to vaccination. Successful vaccination depends upon the correct storage and administration of the vaccine together with the animal’s ability to respond. This can be influenced by such factors as genetic constitution, intercurrent infection, age, the presence of maternally derived antibodies, nutritional status, concurrent drug therapy and stress.