NETWORK FAIL BRIEFING PAPER Getting UK Rail Back on Track

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia

Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Contents Foreword 3 Looking Ahead 5 Priorities in Detail • Great Eastern Main Line 6 • West Anglia Main Line 6 • Great Northern Route 7 • Essex Thameside 8 • Branch Lines 8 • Freight 9 A five county alliance • Norfolk 10 • Suffolk 11 • Essex 11 • Cambridgeshire 12 • Hertfordshire 13 • Connecting East Anglia 14 Our counties connected 15 Foreword Our vision is to release the industry, entrepreneurship and talent investment in rail connectivity and the introduction of the Essex of our region through a modern, customer-focused and efficient Thameside service has transformed ‘the misery line’ into the most railway system. reliable in the country, where passenger numbers have increased by 26% between 2005 and 2011. With focussed infrastructure We have the skills and enterprise to be an Eastern Economic and rolling stock investment to develop a high-quality service, Powerhouse. Our growing economy is built on the successes of East Anglia can deliver so much more. innovative and dynamic businesses, education institutions that are world-leading and internationally connected airports and We want to create a rail network that sets the standard for container ports. what others can achieve elsewhere. We want to attract new businesses, draw in millions of visitors and make the case for The railways are integral to our region’s economy - carrying more investment. To do this we need a modern, customer- almost 160 million passengers during 2012-2013, an increase focused and efficient railway system. This prospectus sets out of 4% on the previous year. -

National Rail Conditions of Travel

i National Rail Conditions of Travel From 5 August 2018 NATIONAL RAIL CONDITIONS OF TRAVEL TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL RAIL CONDITIONS OF TRAVEL Part A: A summary of the Conditions 3 Part B: Introduction 4 Conditions 5 Part C: Planning your journey and buying your Ticket 5 Part D: Using your Ticket 11 Part E: Making your Train Journey 15 Part F: Your refund and compensation rights 21 Part G: Special Conditions applying to Season Tickets 26 Part H: Lost Property 29 Appendix A: List of Train Companies to which the National Rail Conditions of Travel apply as at 5 August 2018 30 Appendix B: Definitions 31 Appendix C: Code of Practice: Arrangements for interview meetings with applicants in connection with duplicate season tickets 33 These National Rail Conditions of Travel apply from 5 August 2018. Any reference to the National Rail Conditions of Carriage on websites, Tickets, publications etc. refers to these National Rail Conditions of Travel. Part A: A summary of the Conditions The terms and conditions of these National Rail Conditions of Travel are set out below in Part C to Part H (the “Conditions”). They comprise the binding contract that comes into effect between you and the Train Companies1 that provide scheduled rail services on the National Rail Network, when you purchase a Ticket. This summary provides a quick overview of the key responsibilities of Train Companies and passengers contained in the contract. It is important, however, that you read the Conditions if you want a full understanding of the responsibilities of Train Companies and passengers. -

Firstgroup Vies with Virgin in West Coast Rail Bidding War | Business | Guardian.Co.Uk Page 1 of 2

FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war | Business | guardian.co.uk Page 1 of 2 Printing sponsored by: FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war Aberdeen-based group is frontrunner, along with incumbent, in battle to secure 14-year franchise contract Dan Milmo, industrial editor guardian.co.uk, Sunday 15 July 2012 14.13 BST Virgin, the current holders of the west coast franchise, pay an annual premium of £150m to the government. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian FirstGroup has emerged as a frontrunner for the multibillion-pound west coast rail franchise alongside incumbent Virgin Trains, with the contest now a two-horse race between the experienced operators. Aberdeen-based FirstGroup is vying with Virgin despite announcing last year that it is handing back its Great Western rail contract three years ahead of schedule, avoiding more than £800m in payments to the government. The Department for Transport is expected to bank a considerable windfall from the new 14-year west coast contract, with Virgin currently paying an annual premium of about £150m to the state. Both bidders are expected to promise an even bigger number over the life of the new franchise. The winner is expected to be announced next month. It is understood that FirstGroup and Virgin are still in talks with the DfT, but two foreign-owned bidders on the four-strong shortlist are no longer considered likely contenders. They are a joint venture between public transport operator Keolis and SNCF, the French state rail group, and a bid from Abellio, which is controlled by the Dutch national rail operator. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for North East Combined Authority

Leadership Board Tuesday 19th April 2016 at 2.00 pm Meeting to be held at Sunderland Civic Centre, Burdon Road, Sunderland, SR2 7SN www.northeastca.gov.uk AGENDA Page No 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Declarations of Interest Please remember to declare any personal interest where appropriate both verbally and by recording it on the relevant form (to be handed to the Democratic Services Officer). Please also remember to leave the meeting where any personal interest requires this. 3. Minutes of the Previous Meeting held on 19 January 2016 1 - 8 4. Minutes of the Extraordinary Meeting held on 24 March 2016 9 - 14 5. Updates from Thematic Leads (a) Economic Development and Regeneration 15 - 22 (b) Employability and Inclusion 23 - 32 (c) Transport 33 - 44 6. Financial Update and Treasury Management Annual Review 45 - 68 7. Date and Time of Next Meeting Friday, 13 May 2016 at 3pm at North Tyneside Council (extraordinary meeting) Tuesday, 21 June 2016 at 2pm at Gateshead Council (annual meeting) 8. Exclusion of Press and Public Under section 100A and Schedule 12A Local Government Act 1972 because exempt information is likely to be disclosed and the public interest test against disclosure is satisfied. 9. Implementing the North East JEREMIE 2 Fund Members are requested to note the intention to circulate the above report on a supplemental agenda in accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985 10. Tyne Pedestrian and Cyclist Tunnels: Tender Report Members are requested to note the intention to circulate the -

London and the South East of England: 15 July 2016

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (LONDON AND THE SOUTH EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2359 PUBLICATION DATE: 15 July 2016 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 05 August 2016 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (London and the South East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/07/2016 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (London and the South East of England) Ivy House 3 Ivy Terrace Eastbourne BN21 4QT The public counter at the Eastbourne office is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. -

Red Bank Manchester Decision Document

15 October 2018 Network licence condition 7 (land disposal): Red Bank Former Carriage Sidings, Collyhurst Road, Manchester Decision 1. On 16 August 2018, Network Rail gave notice of the intention to dispose of land at Red Bank Former Carriage Sidings, Collyhurst Road, Manchester (the land), in accordance with paragraph 7.2 of condition 7 of Network Rail’s network licence. The land and disposal is described in more detail in the notice (copy attached). 2. We have considered the information supplied by Network Rail including the responses received from third parties consulted. For the purposes of condition 7 of Network Rail’s network licence, ORR consents to the disposal of the land in accordance with the particulars set out in the notice. Network Rail’s proposals 3. The land which forms Network Rail’s proposals comprises three sites: the ‘Red Bank’ former carriage sidings (shown as Area 1 on plan 6438292-1); the ‘Red Bank’ land and railway arches (shown as Area 2 on plan 6438292-1) - both areas are to be sold to the Far East Consortium; and the site adjacent to Area 1 (shown on plan 6438292-2) is to be acquired by Transport for Greater Manchester. 4. Network Rail’s stakeholder consultation showed that three objections remained unresolved: from First TransPennine Express (FTPE), Arriva Rail North and West Coast Railway Company. All three objections stemmed from a general expectation that increased stabling or depot facilities would be needed in the Manchester area and that existing sites with the potential to accommodate such facilities should not be sold until future requirements were known. -

Great Britain Passenger Rail: the Current Expected Timetable

Great Britain passenger rail: the current expected timetable Franchise Current operator 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Onwards DJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASOND South West Stagecoach West Midlands Govia East Midlands Stagecoach O I South Eastern Govia O I Wales & Borders Arriva InterCity W.C./W.C. Partnership Virgin/Stagecoach O I Cross Country Arriva OI Great Western First Group OI Apr. Chiltern Chiltern OITo Dec. 2021 To Jul. 2022 TSGN Govia O I To Sep. 2021 To Sep. 2023 East West n/a Potential development and competition period InterCity East Coast Stagecoach/Virgin To Mar. 2023 To Mar. 2024 ScotRail Abellio To Apr. 2022 To Apr. 2025 TransPennine Express First Group To Apr. 2023 To Apr. 2025 Northern Arriva To Apr. 2025 To Apr. 2026 East Anglia Abellio To Oct. 2025 To Oct. 2026 Caledonian Sleeper Serco To Apr. 2030 Essex Thameside Trenitalia To Nov. 2029 To Jun. 2030 Concession London Rail Arriva To Apr. 2024 To Apr. 2026 Tyne and Wear PTE Nexus Crossrail MTR To May 2023 To May 2025 MerseyRail Serco/Abellio To Jul. 2028 Based on publicly available information as at 1 April 2017 Key Existing franchise/concession term O OJEU notice expected Extension/direct award I ITT expected Max. length at discretion of DfT/TS Contract award expected New franchise/concession Operated by PTE Nexus Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail of the Year of the Year of the Year of the Year Finance Franchising Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Chambers UK 2015 The Legal 500 Chambers UK 2017 Finance 2016 Finance 2015 Finance 2014 Finance 2013 UK 2016 Stephenson Harwood LLP is a law firm of over 900 people worldwide, including 150 partners. -

Directory of Resources

SETTLE – CARLISLE RAILWAY DIRECTORY OF RESOURCES A listing of printed, audio-visual and other resources including museums, public exhibitions and heritage sites * * * Compiled by Nigel Mussett 2016 Petteril Bridge Junction CARLISLE SCOTBY River Eden CUMWHINTON COTEHILL Cotehill viaduct Dry Beck viaduct ARMATHWAITE Armathwaite viaduct Armathwaite tunnel Baron Wood tunnels 1 (south) & 2 (north) LAZONBY & KIRKOSWALD Lazonby tunnel Eden Lacy viaduct LITTLE SALKELD Little Salkeld viaduct + Cross Fell 2930 ft LANGWATHBY Waste Bank Culgaith tunnel CULGAITH Crowdundle viaduct NEWBIGGIN LONG MARTON Long Marton viaduct APPLEBY Ormside viaduct ORMSIDE Helm tunnel Griseburn viaduct Crosby Garrett viaduct CROSBY GARRETT Crosby Garrett tunnel Smardale viaduct KIRKBY STEPHEN Birkett tunnel Wild Boar Fell 2323 ft + Ais Gill viaduct Shotlock Hill tunnel Lunds viaduct Moorcock tunnel Dandry Mire viaduct Mossdale Head tunnel GARSDALE Appersett Gill viaduct Mossdale Gill viaduct HAWES Rise Hill tunnel DENT Arten Gill viaduct Blea Moor tunnel Dent Head viaduct Whernside 2415 ft + Ribblehead viaduct RIBBLEHEAD + Penyghent 2277 ft Ingleborough 2372 ft + HORTON IN RIBBLESDALE Little viaduct Ribble Bridge Sheriff Brow viaduct Taitlands tunnel Settle viaduct Marshfield viaduct SETTLE Settle Junction River Ribble © NJM 2016 Route map of the Settle—Carlisle Railway and the Hawes Branch GRADIENT PROFILE Gargrave to Carlisle After The Cumbrian Railways Association ’The Midland’s Settle & Carlisle Distance Diagrams’ 1992. CONTENTS Route map of the Settle-Carlisle Railway Gradient profile Introduction A. Primary Sources B. Books, pamphlets and leaflets C. Periodicals and articles D. Research Studies E. Maps F. Pictorial images: photographs, postcards, greetings cards, paintings and posters G. Audio-recordings: records, tapes and CDs H. Audio-visual recordings: films, videos and DVDs I. -

Hull Core Strategy - Contacts List (As at July 2011)

Hull Core Strategy - Contacts List (as at July 2011) Introduction This report provides details about the contacts made during the development of the Hull Core Strategy. It includes contact made at each plan making stage, as follows: • Issues and Options – August 2008 • Emerging Preferred Approach – February 2010 • Core Strategy Questionnaire – September 2010 • Spatial Options – February 2011 • Core Strategy Publication Version – July 2011 A list of Hull Development Forum members (as at July 2011) is also enclosed. This group has met over 15 times, usually on a quarterly basis. The report also sets out the specific and general organisations and bodies that have been contacted, in conformity with the Council’s adopted Statement of Community Involvement. Specific groups are indicated with an asterisk. Please note contacts will change over time. Issues and Options – August 2008 (Letter sent to Consultants/Agents) Your Ref: My Ref: PPI/KG/JP Contact: Mr Keith Griffiths «Title» «First_Name» «Surname» Tel: 01482 612389 «Job_Title» Fax: 01482 612382 Email: [email protected] «Org» th «Add1» Date: 4 August 2008 «Add2» «Add3» «Town» «Postcode» Dear Sir/Madam Hull Core Strategy - issues, options and suggested preferred option Please find enclosed the ‘Hull Core Strategy issues, options and suggested preferred option’ document for your consideration. Your views should be returned to us by the 5 September, 2008 by using the form provided. In particular, could you respond to the following key questions: 1. What do you think to the issues, objectives, options and suggested preferred option set out in the document? 2. How would you combine the options? 3. -

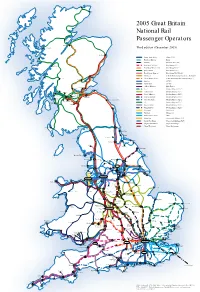

2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall

Thurso Wick 2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall Inverness Kyle of Lochalsh Third edition (December 2005) Aberdeen Arriva Trains Wales (Arriva P.L.C.) Mallaig Heathrow Express (BAA) Eurostar (Eurostar (U.K.) Ltd.) First Great Western (First Group P.L.C.) Fort William First Great Western Link (First Group P.L.C.) First ScotRail (First Group P.L.C.) TransPennine Express (First Group P.L.C./Keolis) Hull Trains (G.B. Railways Group/Renaissance Railways) Dundee Oban Crianlarich Great North Eastern (G.N.E.R. Holdings/Sea Containers P.L.C.) Perth Southern (GOVIA) Thameslink (GOVIA) Chiltern Railways (M40 Trains) Cardenden Stirling Kirkcaldy ‘One’ (National Express P.L.C.) North Berwick Balloch Central Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Gourock Milngavie Cumbernauld Gatwick Express (National Express P.L.C.) Bathgate Wemyss Bay Glasgow Drumgelloch Edinburgh Midland Mainline (National Express P.L.C.) Largs Berwick upon Tweed Silverlink Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Neilston East Kilbride Carstairs Ardrossan c2c (National Express P.L.C.) Harbour Lanark Wessex Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Chathill Wagn Railway (National Express P.L.C.) Merseyrail (Ned-Serco) Northern (Ned-Serco) South Eastern Trains (SRA) Island Line (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) South West Trains (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) Virgin CrossCountry (Virgin Rail Group) Virgin West Coast (Virgin Rail Group) Newcastle Stranraer Carlisle Sunderland Hartlepool Bishop Auckland Workington Saltburn Darlington Middlesbrough Whitby Windermere Battersby Scarborough -

Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 62 STATEMENT OF INCOME 65 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL 76 LIST OF SHAREHOLDINGS STATEMENTS 62 BALANCE SHEET 86 AUDITOR’S REPORT > 67 Notes to the balance sheet > 62 Assets > 71 Notes to the statement > 86 Report on the financial > 62 Equity and liabilities of income statements > 86 Report on the management 63 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS > 72 Notes to the statement of cash flows report 64 FIXED AssETS SCHEDULE > 72 Other disclosures 62 DEUTSCHE BAHN AG 2014 MANAGEMENT REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENT OF INCOME JAN 1 THROUGH DEC 31 [€ mILLION] Note 2014 2013 Inventory changes 0 0 Other internally produced and capitalized assets 0 – Overall performance 0 0 Other operating income (16) 1,179 1,087 Cost of materials (17) –95 –91 Personnel expenses (18) –324 –303 Depreciation –10 –12 Other operating expenses (19) –970 –850 –220 –169 Net investment income (20) 794 583 Net interest income (21) –67 –37 Result from ordinary activities 507 377 Taxes on income (22) 37 –10 Net profit for the year 544 367 Profit carried forward 4,531 4,364 Net retained profit 5,075 4,731 BALANCE SHEET AssETS [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. FIXED ASSETS Property, plant and equipment (2) 29 33 Financial assets (2) 26,836 27,298 26,865 27,331 B. CUrrENT ASSETS Inventories (3) 1 1 Receivables and other assets (4) 4,412 3,690 Cash and cash equivalents 3,083 2,021 7,496 5,712 C. PREpaYMENTS anD AccrUED IncoME (5) 0 1 34,361 33,044 EQUITY AND LIABILITIES [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. -

On Stage Issue

The newsletter of Stagecoach Group Issue 110 | July 2015 STAGE ON page 2 page 6 INSIDE Memorial award | Greener together megabus.com continues European expansion megabus.com has revealed record advance ticket sales on its new network of domestic coach services in Italy as well as launching two new international routes. More than 30,000 customers purchased tickets during the first week of sales in Italy – higher than the initial sales on any of the company’s other networks in Europe. megabus.com services now link 13 destinations across Italy and passengers have been snapping up bargain fares from just €1 (plus 50 cents booking fee). The major new network of inter-city coach services covers Rome, Milan, Florence, Venice, Naples, Turin, Bologna, Verona, Padua, Siena, Genoa, Sarzana (La Spezia) and Pisa. megabus.com has also created around 100 new jobs through the opening of new bases near Milan megabus.com vehicles at the launch of the new Italian domestic network in Florence and in Florence. In addition, megabus.com recently launched its first base in France, where it has created 35 jobs between London and Milan via Lille, Paris, Lyon from customers has been fantastic. at a depot located near Lyon, from which a new and Turin. “The new routes between London and Milan, and international route now operates between megabus.com Managing Director Edward between Barcelona and Cologne are great news Barcelona, Perpignan, Montpellier, Avignon, Lyon, Hodgson said: “These latest routes mark even for our customers who now have access to even Mulhouse, Freiburg, Karlsruhe, Heidelberg, more expansion of our services in Europe.