Brite Divinity School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Segregation to Independence: African Americans in Churches of Christ

FROM SEGREGATION TO INDEPENDENCE: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN CHURCHES OF CHRIST By Theodore Wesley Crawford Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion August, 2008 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Dr. Dennis C. Dickerson Dr. Kathleen Flake Dr. John S. McClure Dr. Lucius Outlaw To my father, who helped make this possible but did not live to see its completion and To my wife, Kim, whose support is responsible for this project ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION……………………………………………………………………. ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS…………………………………………………….. v INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… vii Chapter I. UNDERSTANDING CHUCHES OF CHRIST……………..……………. 1 Denominational Organization…………………………………………. 1 Churches of Christ Journals………………………………………….... 7 Churches of Christ Schools………………………………………...….. 21 Churches of Christ Lectureships………………………………………. 34 Conclusion……………………………………………………………... 38 II. SEGREGATION…………………………………………………………... 40 White-Imposed Segregation…………………………...……………… 41 The Life and Ministry of Marshall Keeble…………...……………….. 61 Conclusion…………………………………………………………….. 83 III. INDEPENDENCE………………………………………………………… 84 The Foundation of Independence..……….…………………………… 85 African American Independence……………………………………… 98 White Responses to the Civil Rights Movement……………………… 117 A United Effort: The Race Relations Workshops…………………….. 128 Conclusion…………………………………………………………….. 134 iii IV. THE CLOSING OF NASHVILLE CHRISTIAN INSTITUTE…………… 137 -

Theological Education Volume 43, Number 2 ISSUE FOCUS 2008 Issues in Theological Education Stewardship in Education: a World-Bridging Concept Timothy D

Theological Education Volume 43, Number 2 ISSUE FOCUS 2008 Issues in Theological Education Stewardship in Education: A World-Bridging Concept Timothy D. Lincoln Who is it for? The Publics of Theological Research Efrain Agosto Advancing Racial/Ethnic Diversity in Theological Education: A Model for Reflection and Action Fernando A. Cascante-Gómez Crafting Theological Research Carl R. Holladay Theoretical Perspectives on Integrative Learning Sarah Birmingham Drummond Young Evangelical Church Planters Hutz H. Hertzberg Distance Hybrid Master of Divinity: A Course-Blended Program Developed by Western Theological Seminary Meri MacLeod Theological Education in a Multicultural Environment: Empowerment or Disempowerment? Cameron Lee, Candace Shields, Kirsten Oh DB 4100: The God of Jesus Christ— A Case Study for a Missional Systematic Theology Stephen Bevans ISSN 0040-5620 Theological Education is published semiannually by The Association of Theological Schools IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA 10 Summit Park Drive Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15275-1110 DANIEL O. ALESHIRE Executive Editor STEPHEN R. GRAHAM Editor ELIZA SMITH BROWN Managing Editor LINDA D. TROSTLE Assistant Editor For subscription information or to order additional copies or selected back issues, please contact the Association. Email: [email protected] Website: www.ats.edu Phone: 412-788-6505 Fax: 412-788-6510 The Association of Theological Schools is a membership organization of schools in the United States and Canada that conduct post-baccalaureate professional and academic degree programs to educate persons for the practice of ministry and advanced study of the theological disciplines. The Association’s mission is to promote the improvement and enhancement of theological schools to the benefit of communities of faith and the broader public. -

Volume 9, Number 1

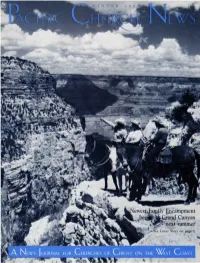

.WINTER 198 amily pjicampment d Canyon ' next summer ' J&: -^See Cover Story on page 2 s A NEWS JOURNAL FOR CHURCHES OF CHRIST ON THE WEST COAST cOVER Family Encampments Continue To Grow 1990 Family he first annual Grand Canyon Family to discover the excitement of Northern Arizona. TEncampment will meet on the Coconino Near the encampment sight are the following Encampments County Fair Grounds at Flagstaff, Arizona, July places of interest: Pioneer Historical Museum; 8-11, 1990. There will be activities scheduled Coconino Center for the Arts; Museum of Red River-June 24-27 in Mather amphitheater on the west rim of Northern Arizona; Fairfield Snow Bowl (ski- Grand Canyon—July 8-11 the Grand Canyon. lift); Sunset Crater National Monument; Yosemite—July 22-27 The new family encampment, co-directed Wupatki National Monument; Monument by Paul Methvin and Edwin White, will make Valley; Oak Creek Canyon—Sedona; Tuzigoot a total of three such programs to serve Christian National Monument; Jerome (an old ghost families in the West. The other two are the town); Montezuma Castle National Monu- Yosemite Family Encampment, directed by Paul ment; Ft. Verde State Historical park; Meteor RCIFIC CHURCH NEWS Methvin, and the Red River Family Crater; Petrified Forest/Painted Desert; Lowell Encampment, directed by Jerry Lawlis. Observatory; Riordan State Park, and others. Volume IX Number 1 The Yosemite Family Encampment The Grand Canyon Family Encampment celebrates its 50th anniversary in 1990. The Red will be a sister to the encampments at Yosemite River Family Encampment, just three years old, and Red River. All three share a common has experienced phenomenal growth. -

Abraham J. Malherbe (1930–2012)

Abraham J. Malherbe (1930–2012) Abraham J. Malherbe, the Buckingham Professor of New Testament Criticism and Literature Emeritus at Yale Divinity School, died suddenly and unexpectedly from an apparent heart attack on Friday afternoon, September 28, at his home in Hamden, CT. A member of The Society of Biblical Literature for over fifty years, Abe was a highly productive scholar who made major contributions in several areas. He is best known for his work in relating early Christianity, especially the Pauline tradition, to the Graeco-Roman world. He made contributions both to Hellenistic moral philosophy and to the ways in which early Christians were influenced by it. His work on The Cynic Epistles: A Study Edition (1977) and Moral Exhortation: A Graeco- Roman Sourcebook (1986) made a number of important texts available to the wider range of scholars. His justly famous “Hellenistic Moralists and the New Testament” (ANRW) may hold the distinction for being the most cited forthcoming article in the history of NT studies. Both before and after its appearance, this article provided a framework for NT scholars to think about how to appropriate Hellenistic moral philosophy. Abe did this in detail in several of his own books, especially Paul and the Thessalonians: The Philosophical Tradition of Pastoral Care (1987), Paul and the Popular Philosophers (1989), and his Anchor Bible Commentary, The Letters to the Thessalonians (2000). He was working on the Hermeneia commentary on the Pastorals when he died. Abe’s strong interest in Paul’s letters led him to give special attention to the theory and practice of writing letters in the Greek and Roman worlds. -

Program Sessions

PROGRAM SESSIONS Gabriel Said Reynolds, University of Notre Dame THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 21 On Doublets and Redactional Criticism of the Qur’an (20 min) Discussion (7 min) 22 NOVEMBER FRIDAY, Saqib Hussain, Oxford University S21-101 Surat al-Waqi’ah (Q 56) as a Group-Closing Surah (20 min) SBL NRSV Editorial Board Discussion (22 min) 9:00 AM–5:00 PM Hilton Bayfront - Cobalt 501B (Fifth Level) S22-101 SBL Regional Coordinators Committee FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 22 9:00 AM–12:00 PM Convention Center - 19 (Mezzanine Level) S22-100 SBL Poverty in the Biblical World Section S22-102 8:30 AM–5:00 PM SBL Status of Women in the Profession Committee Offsite - Offsite 9:00 AM–5:00 PM Theme: Off-Site Session on Poverty, Ecology, and Immigration Hilton Bayfront - Aqua 314 (Third Level) In partnership with the University of San Diego and the Trans-Border Institute, this off-site meeting will gather biblical scholars, faith leaders, and community-based organizations for a day of listening and learning S22-102a (=A22-110) at the US/Mexico border. The intensely politicized and conflict- driven narratives about the border in the national news media obscure SBL THATCamp - The Humanities and Technology Camp some of the daily realities of the bi-national, cross-border region 9:00 AM–5:00 PM between Tijuana and San Diego, which is the busiest international Convention Center - 24C (Upper Level East) border crossing in the world. This meeting will explore the impact of immigration and environmental issues on both sides of the border, and Theme: THATCamp - The Humanities and Technology Camp the ways in which the Bible has and can be used as a resource toward The advent of digital technology and social media has not only deepening compassion, cooperation and a recognition of our common transformed how today religious communities function, they have also humanity. -

John Haralson Hayes Professor Emeritus of Old Testament Candler School of Theology, Emory University (1934–2013)

John Haralson Hayes Professor Emeritus of Old Testament Candler School of Theology, Emory University (1934–2013) John Haralson Hayes was born in rural Abanda, Alabama in 1934, one of seven children in a sharecropper’s home. Seventy-three years later, he retired as Franklin N. Parker Professor of Old Testament at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology in 2007. In his remarkable and celebrated career, he published over forty books and numerous scholarly articles, directed twenty-five PhD dissertations, taught a generation of ministerial students, and served Baptist congregations in three states. Hayes always remembered his rural Alabama roots with great pride. As he approached retirement, he moved back to Alabama, not far from his birthplace, and began farming. In spite of his family’s limited financial resources, Hayes managed to attend and graduate from Howard College (present-day Samford University) in 1956, and completed seminary training at Princeton Theological Seminary in 1960, by which time the faculty had clearly recognized his intellectual promise. He went on to earn a PhD from the institution in 1964. He taught for several years at Trinity University in San Antonio before his appointment to the faculty at Emory University, where he concluded his career. Hayes left lasting contributions as an interpreter of the prophetic literature and, more broadly, as a historian, especially through the two volumes he produced with J. Maxwell Miller: Israelite and Judean History (1976) and A History of Ancient Israel and Judah (1986, 2006). Yet as a true polymath, Hayes published in a wide range of areas: the history of biblical interpretation, archaeology, theology, and the exegesis of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament through a wide range of critical methodologies, with a particular focus on form criticism. -

The 2015 Dean's Report

The 2015 Dean’s Report DUKE DIVINITY SCHOOL “ You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.” — Matthew 22:37 These years at Duke are your best opportunity to learn to love God with all your intellectual capacity. This is the time for the sanctification of your intellect. Don’t miss this opportunity. It is a privilege to take our place among Christians through the centuries—and there are not so many of them—who are called to love God through the sanctification of our intellects. That is the chief purpose for which you were called here ... Study as a witness of faith. — Excerpted from the Opening Convocation sermon preached by Interim Dean Ellen F. Davis on August 25, 2015 The 2015 Dean’s Report DUKE DIVINITY SCHOOL Message from the Dean: A Year of Transition 2 Gratitude for Our Gifts and a Focus on the Future A Process of Discernment 6 Report from the Dean Search Committee Ensuring Priorities Are Met 10 New Leadership Positions Devote Attention to Key Areas Commemorating a Scholar and Mentor American Church History Professor Grant Wacker Retires 14 Refurbishing the Divinity Library 18 A Photo Report on Library Enhancements Partnering Together 20 A Record-Setting Year for Giving The Year in Review 2015 Highlights from Duke Divinity School 24 Facts and Figures 34 Annual Financial Report 35 Boards and Administration 36 MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN A Year of Transition Gratitude for Our Gifts and a Focus on the Future Ellen F. Davis Interim Dean and Amos Ragan Kearns Distinguished Professor of Bible and Practical Theology Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good; yes, God’s faithfulness is boundless. -

Curriculum Vitae

July 2, 2012 HAROLD W. ATTRIDGE Curriculum Vitae I. Personal Born: November 24, 1946 Address: 459 Prospect St., New Haven, CT 06511 and 2 Island Bay Circle, Guilford, CT 06437 Married: Janis Ann Farren Children: Joshua (born 7/20/73); Rachel (born 5/19/78) II. Employment 2012- Sterling Professor of Divinity 2002– 2012 Dean, Yale Divinity School, named the Reverend Henry L. Slack Dean, 2009 1997– 2012 Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School 1991– 97 Dean, College of Arts and Letters University of Notre Dame 1988– 97 Professor, Department of Theology, University of Notre Dame 1985– 87 Associate Professor, Department of Theology, University of Notre Dame 1982– 85 Associate Professor of New Testament, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University 1977– 82 Assistant Professor of New Testament, Perkins School of Theology III. Education 1974– 77 Junior Fellow, Society of Fellows, Harvard University 1969– 74 Harvard University. Ph.D. (1975) 1972– 73 Hebrew University of Jerusalem (supported by a traveling fellowship from Harvard.) 1967– 69 Cambridge University: as a Marshall Scholar, read Greek Philosophy for Part II of the Classical Tripos. B.A. (1969), M.A. (1973) 1963– 67 Boston College, Classics, A.B., summa cum laude IV. Professional Activities Memberships: Catholic Biblical Association, 1974– Consultor (Member of Executive Board), 2006– 07 Board of Trustees, 2007– 09 Vice– President, 2010– 11 President, 2011-12 International Association for Coptic Studies, 1975– North American Patristics Society, 1986– -

15 Notes on Contributors 2020

The Studia Philonica Annual 32 (2020): 354–356 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS Marta Alesso is Titular Professor of Greek language and literature in the Faculty of Human Sciences at the National University of La Pampa, Argentina. Her postal address is Pestalozzi 625, 6300 Santa Rosa, La Pampa, Argentina; her electronic address is [email protected]. Maureen Attali is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of History of the University of Fribourg and also a Research Associate at the Sorbonne University in Paris. Her postal address is Rue Pierre Aeby 16, 1700 Fribourg, Switzerland; her electronic address is maureen.attali@ gmail.com. Harold W. Attridge is the Sterling Professor of Divinity Emeritus, Yale Divinity School. His postal address is 600 Prospect St., A-8, New Haven, CT 06511 U.S.A.; his electronic address is [email protected]. Ellen Birnbaum has taught and/or conducted postdoctoral research at several Boston-area institutions, including Boston University, Brandeis, and Harvard. Her postal address is 36 Highland Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, U.S.A.; her electronic address is [email protected]. Anne Boiché teaches classical languages at the Lycée Clemenceau in Ville- momble and Biblical Greek at the Institut Catholique de Paris. Her postal address is 96 avenue Philippe-Auguste, 75011 Paris, France; her electro- nic address is anne_boiche@ hotmail.com. Adela Yarbro Collins is Buckingham Professor Emerita of New Testa- ment Criticism and Interpretation, Yale Divinity School. Her postal address is 102 Leetes Island Road, Guilford, CT 06437, U.S.A.; her elec- tronic address is [email protected]. John J. Collins is Holmes Professor of Old Testament at Yale Divinity School. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE GREGORY E. STERLING Reverend Henry L. Slack Dean of Yale Divinity School Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament 409 Prospect Street New Haven, CT 06511 [email protected] BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION EDUCATION 1990 Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, Ph.D. (Biblical Studies/New Testament) 1982 University of California, Davis, M.A. (Classics) 1980 Pepperdine University, M.A. (Religion) 1979 University of Houston, Post-baccalaureate (Classics) 1978 Houston Baptist University, B.A. (Christianity and History; graduated first in class) 1975 Florida College, A.A. (Biblical Studies; graduated first in class) EMPLOYMENT EXPERIENCE Academic 2012- Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament, Yale Divinity School, Yale University 2000-01 Visiting Professor, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Institute for Advanced Studies 2000-2012 Professor of Theology (New Testament and Christian Origins), University of Notre Dame 1995-2000 Associate Professor of Theology (New Testament and Christian Origins), University of Notre Dame 1990-95 Assistant Professor of Theology (New Testament and Christian Origins), University of Notre Dame 1989-90 Visiting Assistant Professor of Theology (New Testament and Christian Origins), University of Notre Dame 1983, 84, 87 Fellow, Graduate Theological Union 1987 Adjunct Faculty, New College Berkeley 1982 Teaching Graduate Assistant, University of California (Davis) Administrative 2012- Reverend Henry L. Slack Dean of Yale Divinity School 2008-2012 Dean of the Graduate School 2007 Acting Dean, College of Arts an d Letters (January-August) 2006-2008 Executive Associate Dean, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame 2004-2006 Senior Associate Dean, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame 2 2001-2008 Associate Dean of the Faculty, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame 1997-2001 Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Theology, University of Notre Dame 1993 Acting Director of the M.A. -

Yaie Diviníty School Saturday, October 27, 2Ot2 1O:Oo AM Order of the Program

A Service in C elebr qtion and Thanksg iving For Abrqhqm I. Malherbe 1930 - 2072 Marquand Chapel YaIe Diviníty School Saturday, October 27, 2ot2 1o:oo AM Order of the Program Gathering Music Jean Showalter Organ Prelude Prelude in e Minor J. S. Bach Jean Showalter Call to Praise Gregory E. Sterling Leader: Our help is in the Name of the Lord. Congregation: The Maker of heaven and earth. Leader: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. Congregation: Praise the Lord! Welcome Gregory E. Sterling Hymn "O Lord Most Holy" (Solo) Cesar Franck Barbara Kaechele Prayer James Thompson Eternal God, source of all mercies, We praise you for the company of all who have finished their course in faith and now rest from their labors. We gather in remembrance of your servant, Abraham Malherbe, giving thanks for his life and work. Come to us in this company with your lovingkindess; Comfort, strengthen and confirm us in your Word. Help us to believe where we have not seen, that your presence may lead us through our years and bring us at last with all your beloved into the joy of your home, eternal in the heavens. Through fesus Christ our Lord. Amen. *Hymn "All Hail the Power of Jesus' Name" Darwin Keichline First Reading and a Family Remembrance Selina Malherbe Brooks Psalm r3gi r-rz Second Reading and Personal Remembrance fohn T. Fitzgerald Matthew 13:44-45, 'r-1¡z Third Reading Kathryn Greene-McCreight r Thessalonians z:t-r2 Remembrance and Tribute Carl Holladay Silent Reflection Hymn "There is a Balm in Gilead" (Solo) Traditional American Spiritual John Taylor Ward A Litany of Thanksgiving Stephen Peterson Congregation responding to each petition: Your steadfast love endures forever (Psalm 136) Commendation Gregory E. -

Office: Emory University, Candler School of Theology, Rita Anne Rollins Building 548, 1531 Dickey Drive, Atlanta, GA 30322. Tele

CURRICULUM VITAE Carl R. Holladay Office: Emory University, Candler School of Theology, Rita Anne Rollins Building 548, 1531 Dickey Drive, Atlanta, GA 30322. Telephone (404) 727-4017; FAX (404) 727-2494; email: [email protected] Education. A.A., Freed-Hardeman University, Henderson, TN, 1963; B.A., Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX, 1965; M.Div., Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX, 1969; Th.M., Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton, NJ, 1970; Ph.D., University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England, 1975 Areas of Academic Specialization. New Testament, Christian Origins, Hellenistic Judaism Academic Employment. Lecturer in New Testament Studies, Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX, 1972 (summer); Asst. Prof. of New Testament, Yale Divinity School, New Haven, CT, 1975-78; Assoc. Prof. of New Testament, 1978-80; Assoc. Prof. of New Testament, Candler School of Theology, Emory University, 1980-90; Professor of New Testament, 1990-2002; Charles Howard Candler Professor of New Testament, 2002-; Associate Dean, 1983-91; Acting Dean, 1985; Dean of the Faculty and Academic Affairs, 1992-94; Co-Director, Graduate Division of Religion, 2010-12 Honors and Awards. B.A., summa cum laude, Abilene Christian University, 1965; F. J. A. Hort Memorial Fund Award, Cambridge University, 1973. Travel grant for study at the Institutum Judaicum Delitzchianum, Münster, Germany; A. Whitney Griswold Faculty Research Grant, Yale University, 1976, 1979; elected to membership in Studiorum Novi Testamenti Societas, 1979; Herbert G. May Memorial Lecturer, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH. May 3, 1992; Emory University Research Committee release time award for research during the 1987-88 academic year; Fulbright Senior Scholar Award for research at Eberhard-Karls Universität, Tübingen, Germany, 1994-95; William M.