Sk7 Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE THE RT. REV. CHRISTOPHER A. HARPER ORDINATION As Deacon on February 6, 2005, St. Thomas’ Church, Huron Str. Toronto, Ont., Diocese of Saskatchewan As Priest on October 16, 2005, St. Alban’s Cathedral, Prince Albert, Diocese of Saskatchewan As Bishop onNovember 17, 2018, St. John the Evangelist Cathedral, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan FORMAL POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION Wycliffe College, Toronto, Ontario UofT /TST Masters of Divinity 2002-2005 James Settee College, Diocese of Saskatchewan 1996-2001 Certificate of Indigenous Anglican Theology Southern Alberta Institute of Technology 1995-2002 EMT-A(Advanced) Saskatchewan Institute of Technology 1984 Emergency Medical Technician CHURCH APPOINTMENTS Lay Reader, Lay Minister in Charge - Diocese of Saskatchewan 1996-2005 For the Mission of Fort Pitt and Onion Lake, Saskatchewan President of Lay Reader Association, Diocese of Saskatchewan 1997-2002 Internship as Student Mission of Fort Pitt and Onion Lake, Saskatchewan Summer of 2003 & 2004 Internship as Student Sept-May 2003-04, 2004-05 St. Thomas’ Anglican Church, Huron Str. Toronto. Ont. Deacon May 05-Oct.05 For the Mission of Fort Pitt and Onion Lake, Saskatchewan Deacon THE RT. REV. CHRISTOPHER A. HARPER PAGE 2 For the Parish of Birch Hills/Kinistino/ Muskoday, Saskatchewan Oct.01-20, 2005 Priest/ Rector / Warden of Lay Readers Diocese of Saskatchewan For the Parish of Birch Hills/Kinistino/Muskoday, Saskatchewan Oct.2005 – Sept. 16/ 2012 The Parish has three full time points; St. Mary’s, Birch Hills/ St. James, Muskoday First Nation/ St. Georges Anglican and Zion Lutheran, Kinistino Sask. It encompasses 6 part-time summer churches and 10 communities/ towns. Within Kinistino parish I served as a Lutheran Pastor every other month with the blessing and commission of ELCIC Saskatchewan Synod under Bishop Cindy Halmarson. -

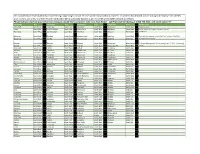

Saskatchewan Intraprovincial Miles

GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES The miles shown in Section 9 are to be used in connection with the Mileage Fare Tables in Section 6 of this Manual. If through miles between origin and destination are not published, miles will be constructed via the route traveled, using miles in Section 9. Section 9 is divided into 8 sections as follows: Section 9 Inter-Provincial Mileage Section 9ab Alberta Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9bc British Columbia Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9mb Manitoba Intra-Provincial Mileage Section9on Ontario Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9pq Quebec Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9sk Saskatchewan Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9yt Yukon Territory Intra-Provincial Mileage NOTE: Always quote and sell the lowest applicable fare to the passenger. Please check Section 7 - PROMOTIONAL FARES and Section 8 – CITY SPECIFIC REDUCED FARES first, for any promotional or reduced fares in effect that might result in a lower fare for the passenger. If there are none, then determine the miles and apply miles to the appropriate fare table. Tuesday, July 02, 2013 Page 9sk.1 of 29 GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES City Prv Miles City Prv Miles City Prv Miles BETWEEN ABBEY SK AND BETWEEN ALIDA SK AND BETWEEN ANEROID SK AND LANCER SK 8 STORTHOAKS SK 10 EASTEND SK 82 SHACKLETON SK 8 BETWEEN ALLAN SK AND HAZENMORE SK 8 SWIFT CURRENT SK 62 BETHUNE -

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways Updated September 2011 Meadow Lake Big River Candle Lake St. Walburg Spiritwood Prince Nipawin Lloydminster wo Albert Carrot River Lashburn Shellbrook Birch Hills Maidstone L Melfort Hudson Bay Blaine Lake Kinistino Cut Knife North Duck ef Lake Wakaw Tisdale Unity Battleford Rosthern Cudworth Naicam Macklin Macklin Wilkie Humboldt Kelvington BiggarB Asquith Saskatoonn Watson Wadena N LuselandL Delisle Preeceville Allan Lanigan Foam Lake Dundurn Wynyard Canora Watrous Kindersley Rosetown Outlook Davidson Alsask Ituna Yorkton Legend Elrose Southey Cupar Regional FortAppelle Qu’Appelle Melville Newcomer Lumsden Esterhazy Indian Head Gateways Swift oo Herbert Caronport a Current Grenfell Communities Pense Regina Served Gull Lake Moose Moosomin Milestone Kipling (not all listed) Gravelbourg Jaw Maple Creek Wawota Routes Ponteix Weyburn Shaunavon Assiniboia Radwille Carlyle Oxbow Coronachc Regway Estevan Southeast Regional College 255 Spruce Drive Estevan Estevan SK S4A 2V6 Phone: (306) 637-4920 Southeast Newcomer Services Fax: (306) 634-8060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.southeastnewcomer.com Alameda Gainsborough Minton Alida Gladmar North Portal Antler Glen Ewen North Weyburn Arcola Goodwater Oungre Beaubier Griffin Oxbow Bellegarde Halbrite Radville Benson Hazelwood Redvers Bienfait Heward Roche Percee Cannington Lake Kennedy Storthoaks Carievale Kenosee Lake Stoughton Carlyle Kipling Torquay Carnduff Kisbey Tribune Coalfields Lake Alma Trossachs Creelman Lampman Walpole Estevan -

Cumulative Effects Assessment Study Area Legend

450000 500000 550000 600000 650000 MONTREAL LAKE 106 Legend Project Location Hwy 120 Hwy913 Airport Hwy 264BITTERN LAKE 218 Hwy 265 Regional Study Area Communities Hamlets Candle Lake Other Communities Hwy 926 Rural Road Hwy 123 Existing Road Hwy 2 Proposed Access Road 5950000 5950000 Hwy 952 Hwy 953 Highway Watercourse Tobin Lake Waterbody LITTLE RED RIVER 106D Hwy 263 TORCH RIVER MONTREAL LAKE 106B Hwy 35 Rural Municipality Hwy 106Hwy Choiceland Garrick CARROT RIVER 29A Hwy 55 Smeaton Love FALC Boundary LITTLE RED RIVER 106C White Fox Shipman RED EARTH 29 CEA Study Area Meath Park Weirdale x River First Nations Reserve Hwy 355 Albertville Whitefo Hwy 255 Hwy STURGEON LAKE 101 Nipawin Hwy 55 GARDEN RIVER MISTAWASIS 103C BUCKLAND Codette Carrot River WAHPETON 94A n River iver ewa n R Shellbrook rth Saskatch wa NIPAWIN No che kat Sas 5900000 5900000 Hwy 302 KISKACIWAN 208 Aylsham Hwy 23 Hwy OPAWAKOSCIKAN 201 Hwy 302 Prince Albert r ive KISTAPINAN 211 Hwy 3 R an ew Arborfield ch Hwy 335 at Gronlid PRINCE ALBERT k KINISTINO s a MUSKODAY 99 S Zenon Park th Ridgedale u o WILLOW CREEK S JAMES SMITH CREE NATION Macdowall BIRCH HILLS Fairy Glen CONNAUGHT Weldon Birch Hills Brancepeth Kinistino Scale: 1:750,000 Hwy 25 Hagen 105 0 10 20 Hwy 6 Hwy Beatty St. Louis Kilometres Star City BEARDY'S and OKEMASIS 96,97 Melfort Tisdale Eldersley Hwy 3 Hwy 212 ONE ARROW 95-1F Valparaiso Duck Lake Hwy20 Reference ONE ARROW 95-1D Hwy 225 Hwy 320 FLETT'S SPRINGS STAR CITY TISDALE Base data: NRCan National Road Network; 5850000 ONE ARROW 95-1B 5850000 NTS 1:250,000 -

The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY by AUTHORITY of the QUEEN’S PRINTER/Publiée Chaque Semaine Sous L’Autorité De L’Imprimeur De La Reine

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART II (REVISED REGULATIONS) or PART III (REGULATIONS)/ CE NUMÉRO NE CONTIENT PAS DETHE PARTIE SASKATCHEWAN II GAZETTE, OCTOBER 21, 2011 2161 (RÈGLEMENTS RÉVISÉS) OU DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’ImPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 107 REGINA, friday, OCTOBER 21, 2011/REGINA, VENDREDI, 21 OCTOBRE 2011 No. 42/nº 42 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAY/JOUR SPÉCIAUX ...................................................................................................................................................... 2162 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ..................................................................................... 2162 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION (Fourth Session, Twenty-sixth Legislative Assembly/Quatrième session, 26e Assemblée législative) ............................................ 2165 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR À DES OCCURRENCES PARTICULIÈRES..... 2166 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2011) ........................................................................................................................ 2166 MINISTERS’ ORDERS/ARRÊTÉS MINISTÉRIELS ...................................................................................................................... 2167 The Municipalities Act ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Contact: [email protected] 306-463-6383

www.the-chronicle.ca Contact: [email protected] 306-463-6383 Deadline for Jan. 25 Chronicle is Jan. 20 Jan. 18, 2021 Attention …. people to govern, others go to school for years to learn about Common Sense Has Left The Building! health issues and average people like me need to rely on these people to help me navigate the convoluted waters of opinions According to The Canadian TaxPayers Federation, Canada’s that are rampant on social media platforms. If someone would national debt is in excess of 1 trillion dollars and growing at the have told me 10 years ago that so many of my belief systems staggering rate of 43.5 million dollars per day. In the 6 years would be challenged by a media based in some fact, no fact, since Justin Trudeau ascended to the top spot in Canada, Can- rumors or opinions, and that I would be expected to base my ada’s debt has almost doubled. No small feat for sure. South of opinions on this platform, then I would have called you crazy. the border the situation is even more grim with a National debt For now I choose to listen to my family Dr. for my medical ad- of over 27 trillion and civil unrest at a place not seen since the vice. For now I will trust that people I voted for in my Govern- Civil War. ment are there to make the laws I will follow, and that I will get the opportunity to change those leaders every so many years. -

Umaas Members

UMAAS MEMBERS - 2021 AS OF DATE: 31-May-21 X ACKERMAN BRENNA BOX 1120 GRENFELL S0G 2B0 1 2015 1099 X ADAMS CHRIS BOX 460 WALDHEIM S0K 4R0 6 1993 1213 X AKHTAR HASAN BOX 5000, LARONGE, SK. GOVT RELATIONS S0J 1L0 2015 X ALAM ASHRAFUL BOX 40 BATTLEFORD S0M 0E0 6 2019 4429 X AMBROSE KATHLEEN BOX 205 ENDEAVOUR S0A 0W0 3 2000 64 X ANDERSON JANELLE BOX 200 CABRI S0N 0J0 2 2016 390 X ANDERSON EILEEN BOX 10 MORTLACH S0H 3E0 2 2018 261 X ANTHONY KATHY BOX 6 ALIDA S0C 0B0 1 2009 120 X ANTONIUK VALERIE BOX 5000, LARONGE, SK. GOVT RELATIONS S0J 1L0 2007 X AUDETTE HEATHER BOX 2005 MELFORT S0E 1A0 5 2006 5992 X AUDETTE RODNEY BOX 209 BETHUNE S0G 0H0 2 1992 401 X BABBINGS MYRNA JEAN BOX 152; GLEN EWEN, SK; S0C 1C0 ALAMEDA S0C 0R0 1 1997 144 X BACON RHONDA BOX 84 KINISTINO SOJ 1H0 5 2009 654 X BAILEY CHERYL BOX 505 EATONIA S0L 0Y0 4 2005 524 X BAILEY SHAUNA BOX 10 FINDLATER S0G 1P0 3 2021 45 X BAKER CAREY BOX 1030 UNITY S0K 4L0 4 2014 2573 X BANNERMAN LORRIE BOX 370; LIVELONG,SK; S0M 1J0 TURTLE VIEW 2020 119 X BARONI MARTY BOX 394 BIGGAR S0K 0M0 4 2012 2226 X BARTCH OLIVIA BOX 160 STENEN S0A 3X0 3 2003 100 X BAUMGARTNER CINDY BOX 123 WHITEWOOD S0G 5C0 1 2010 862 X BEAL MARILYN BOX 38 WHITE FOX S0J 3B0 5 2003 355 X BEARSS ANNA BOX 730 WATROUS S0K 4T0 3 2020 1900 X BEATTY MARJ BOX 1102; GRENFELL, SK S0G 2B0 2021 X BEATTY-HENFREY SHERRY BOX 37 BULYEA S0G 0L0 3 2020 113 X BEAUDOIN DARRIN BOX 10; MAYMONT, SK; S0M 1T0 RICHARD 6 1987 21 X BECKETT SANDRA BOX 92; LANDIS, SK; S0K 2K0 WILKIE S0K 4W0 6 2003 1301 X BENDIG JUANETA BOX 74; BRUNO, SK; S0K 0S0 MEACHAM S0K 2V0 5 2011 99 X BERLIN HEIDI BOX 342 BALGONIE S0G 0E0 1 2014 1745 X BERNIER DENISE BOX 160 MAYMONT S0M 1T0 6 2015 138 X BERRY CINDY BOX 125 NEVILLE S0N 2V0 2 2014 87 X BEST LANI BOX 162; ENGLEFELD,SK; S0K 1N0 WATSON 5 2009 667 X BJERLAND VALERIE BOX 473, ROSE VALLEY, SK. -

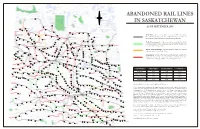

Abandoned Rail Lines in Saskatchewan

N ABANDONED RAIL LINES W E Meadow Lake IN SASKATCHEWAN S Big River Chitek Lake AS OF SEPTEMBER 2008 Frenchman Butte St. Walburg Leoville Paradise Hill Spruce Lake Debden Paddockwood Smeaton Choiceland Turtleford White Fox LLYODMINISTER Mervin Glaslyn Spiritwood Meath Park Canwood Nipawin In-Service: rail line that is still in service with a Class 1 or short- Shell Lake Medstead Marshall PRINCE ALBERT line railroad company, and for which no notice of intent to Edam Carrot River Lashburn discontinue has been entered on the railroad’s 3-year plan. Rabbit Lake Shellbrooke Maidstone Vawn Aylsham Lone Rock Parkside Gronlid Arborfield Paynton Ridgedale Meota Leask Zenon Park Macdowell Weldon To Be Discontinued: rail line currently in-service but for which Prince Birch Hills Neilburg Delmas Marcelin Hagen a notice of intent to discontinue has been entered in the railroad’s St. Louis Prairie River Erwood Star City NORTH BATTLEFORD Hoey Crooked River Hudson Bay current published 3-year plan. Krydor Blaine Lake Duck Lake Tisdale Domremy Crystal Springs MELFORT Cutknife Battleford Tway Bjorkdale Rockhaven Hafford Yellow Creek Speers Laird Sylvania Richard Pathlow Clemenceau Denholm Rosthern Recent Discontinuance: rail line which has been discontinued Rudell Wakaw St. Brieux Waldheim Porcupine Plain Maymont Pleasantdale Weekes within the past 3 years (2006 - 2008). Senlac St. Benedict Adanac Hepburn Hague Unity Radisson Cudworth Lac Vert Evesham Wilkie Middle Lake Macklin Neuanlage Archerwill Borden Naicam Cando Pilger Scott Lake Lenore Abandoned: rail line which has been discontinued / abandoned Primate Osler Reward Dalmeny Prud’homme Denzil Langham Spalding longer than 3 years ago. Note that in some cases the lines were Arelee Warman Vonda Bruno Rose Valley Salvador Usherville Landis Humbolt abandoned decades ago; rail beds may no longer be intact. -

Call Provincial Scheduling at 1-855-778-4141 and Select Option “2”

The Saskatchewan Health Authority is experiencing a large surge in Covid-19 cases and demand within our system. To address this demand, we are asking SUN employees to identify work streams and areas in which they are interested in being potentially floated, as per Article 45 of the SUN collective agreement. Please Indicate City/Town(s) and Service Line(s) you would like to volunteer to be on a Float Roster - Call Provincial Scheduling at 1-855-778-4141 and select option “2”. City/Town Area Column1City/Town Area Column2City/Town Area Area32City/Town Area Column3Service Lines Arborfield North East Foam Lake South East Mankota South West Shaunavon South West Immunization Arcola South East Fort Qu'Appelle South East Maple Creek South West Shellbrook North East Public Health (including Contact Tracing) Assiniboia South West Gainsborough South East Maryfield South East Smeaton North East HealthLine Balcarres South East Goodsoil North West Meadow Lake North West Spalding South East Assisted Self Isolation Site (ASIS)/ Self Isolation Site (SIS) Battleford North West Grenfell South East Meadow Lake North West Spalding South East Testing & Assessment Beauval North West Gull Lake South West Melfort North East Spiritwood North West Outbreak Management (Continuing Care, OHS/IPC, Screening) Beechy South West Hafford North West Melville South East St George's Hill North West Acute Bengough South East Herbert South West Midale South East St Walburg North West Big River North East Hodgeville South West Middle Lake South East St. Brieux North East Biggar -

Saskatchewan Registered Dietitian Directory for Individual Client Services

Saskatchewan Registered Dietitian Directory for Individual Client Services There are multiple ways to access the individual services of a Registered Dietitian in Saskatchewan. How you access the Dietitian’s services will depend on where you live and what type of service you need. Use our directory to help navigate. It is organized alphabetically by former regional health authority. Tribal councils are included under the heading of the closest former regional health authority. Private practice Dietitians are listed on page 5, alphabetically by the name of the private practice. There are also several free group class options listed on the last page. 1) Dietitian Call Center (Eat Well Saskatchewan) for free nutrition advice: 1-833-966-5541 2) Self-refer! Phone your local health center or the number listed below and ask to speak to the dietitian. 3) Have your family physician or allied health care provider send a referral for dietitian services. 4) Contact a private practice Dietitian who offers fee for service. Check your insurance plan for coverage. Former Regional Heath Dietitian Contact Information ***Unless otherwise stated, the Authority/Organization Dietitian accepts self and allied health provider referral Provincial Resources Canadian Diabetes Association Phone: 306-933-1238 Ext. 2853 Eat Well Saskatchewan Phone: 1-833-966-5541 or [email protected] Health Canada (Canadian Prenatal Nutrition Program) Phone: 306-780-5791 Health Canada (Aboriginal Diabetes Initiatives) Phone:306-780-7246 Sports Medicine and Science Council of Saskatchewan Phone: 975-0849 Former Athabasca Phone: 306-439-2647 Health Authority Former Cypress Health Swift Current, Eastend, Gull Lake, Herbert, Region Hodgeville, Leader, Mankota, Maple Creek, Ponteix, Shaunavon, Vanguard Phone: 306-778-5118 or 1-877-401-8071 Former Five Hills Patient Education Center for all communities in Health Region the Five Hills Health Region Phone: 694-0230 Fax:694-0241 Former Heartland Kerrobert/Macklin/Unity/Wilkie- Health Region Phone: 306-228-4442 Ext. -

Saskatchewan Registered Dietitian Directory for Individual Client Services

Saskatchewan Registered Dietitian Directory for Individual Client Services There are multiple ways to access the individual services of a Registered Dietitian in Saskatchewan. How you access the Dietitian’s services will depend on where you live and what type of service you need. Use our directory to help navigate. It is organized alphabetically by regional health authority. Tribal councils are included under the heading of the closest regional health authorities. Private practice Dietitians are listed on the last page, alphabetically by the name of the private practice. 1. Self-refer! Phone your local health center or the number listed below and ask to speak to the dietitian. 2. Have your family physician or allied health care provider send a referral for dietitian services. 3. Contact a private practice Dietitian who offers fee for service. Check your insurance plan to see if you have coverage. Regional Heath Dietitian Contact Information ***Unless otherwise stated, the Authority/Organization Dietitian accepts self and allied health provider referral Provincial Resources Canadian Diabetes Association Phone: 306-933-1238 Ext. 2853 Health Canada (Canadian Prenatal Nutrition Program) Phone: 306-780-5791 Health Canada (Aboriginal Diabetes Initiatives) Phone:306-780-7246 Sports Medicine and Science Council of Saskatchewan Phone: 975-0849 Athabasca Health Phone: 306-439-2647 Authority Cypress Health Region Swift Current, Eastend, Gull Lake, Herbert, Hodgeville, Leader, Mankota, Maple Creek, Ponteix, Shaunavon, Vanguard Phone: 306-778-5118 or 1-877-401-8071 Five Hills Health Patient Education Center for all communities in Region the Five Hills Health Region Phone: 694-0230 Fax:694-0241 Heartland Health Kerrobert/Macklin/Unity/Wilkie- Region Phone: 306-228-4442 Ext. -

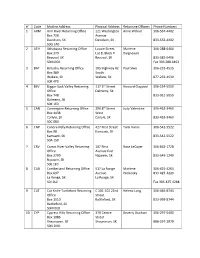

Code Mailing Address Physical Address

#` Code Mailing Address Physical Address Returning Officers Phone Numbers 1 ARM Arm River Returning Office 121 Washington Anne Willner 306-567-4402 Box 728 Avenue Davidson, SK Davidson, SK 833-552-4402 S0G 1A0 2 ATH Athabasca Returning Office Lavoie Street, Marlene 306-288-6460 Box 379 Lot 8, Block P Daigneault Beauval, SK Beauval, SK 833-382-0496 S0M 0G0 Fax 306.288.6463 3 BAT Batoche Returning Office 105 Highway #2 Paul Siwy 306-233-4515 Box 389 South Wakaw, SK Wakaw, SK 877-233-4530 S0K 4P0 4 BSV Biggar-Sask Valley Returning 117 3rd Street Howard Claypool 306-254-5050 Office Dalmeny, SK Box 748 833-921-5050 Dalmeny, SK S0K 1E0 5 CAN Cannington Returning Office 200 8th Street Judy Valentine 306-453-3460 Box 1438 West Carlyle, SK Carlyle, SK 833-453-3460 S0C 0R0 6 CNP Canora-Pelly Returning Office 427 First Street Tami Vanin 306-542-5522 Box 98 Kamsack, SK Kamsack, SK 833-542-5522 S0A 1S0 7 CRV Carrot River Valley Returning 107 First Rose LeCuyer 306-862-1728 Office Avenue East Box 3700 Nipawin, SK 833-649-1240 Nipawin, SK S0E 1E0 8 CUB Cumberland Returning Office 517 La Ronge Marlene 306-425-4263 Box 697 Avenue Wolkosky 833-425-4220 La Ronge, SK La Ronge, SK S0J 1L0 Fax 306-425-4268 9 CUT Cut Knife-Turtleford Returning C 101-102 22nd Helena Long 306-446-8744 Office Street Box 1510 Battleford, SK 833-999-8744 Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 10 CYP Cypress Hills Returning Office 379 Centre Beverly Dunham 306-297-5400 Box 1086 Street Shaunavon, SK Shaunavon, SK 888-297-2979 S0N 2M0 #` Code Mailing Address Physical Address Returning Officers Phone