Behaviour of the Little Raven Corvus Mellori on Phillip Island, Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Species List for Mount Majura

Bird Species List for Mount Majura This list of bird species is based on entries in the database of the Canberra Ornithologists Group (COG). The common English names are drawn from: Christidis, L. & Boles, W.E. (1994) The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories. Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne. (1) List in taxonomic order Stubble Quail Southern Boobook Australian Wood Duck Tawny Frogmouth Pacific Black Duck White-throated Needletail Little Black Cormorant Laughing Kookaburra White-faced Heron Sacred Kingfisher Nankeen Night Heron Dollarbird Brown Goshawk White-throated Treecreeper Collared Sparrowhawk Superb Fairy-wren Wedge-tailed Eagle Spotted Pardalote Little Eagle Striated Pardalote Australian Hobby White-browed Scrubwren Peregrine Falcon Chestnut-rumped Heathwren Brown Falcon Speckled Warbler Nankeen Kestrel Weebill Painted Button-quail Western Gerygone Masked Lapwing White-throated Gerygone Rock Dove Brown Thornbill Common Bronzewing Buff-rumped Thornbill Crested Pigeon Yellow-rumped Thornbill Glossy Black-Cockatoo Yellow Thornbill Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo Striated Thornbill Gang-gang Cockatoo Southern Whiteface Galah Red Wattlebird Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Noisy Friarbird Little Lorikeet Regent Honeyeater Australian King-Parrot Noisy Miner Crimson Rosella Yellow-faced Honeyeater Eastern Rosella White-eared Honeyeater Red-rumped Parrot Fuscous Honeyeater Swift Parrot White-plumed Honeyeater Pallid Cuckoo Brown-headed Honeyeater Brush Cuckoo White-naped Honeyeater Fan-tailed -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

The Australian Raven (Corvus Coronoides) in Metropolitan Perth

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1997 Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth P. J. Stewart Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, P. J. (1997). Some aspects of the ecology of an urban Corvid : The Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) in metropolitan Perth. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/295 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids

72 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 72-82 Some Vocal Characteristics and Call Variation in the Australian Corvids CLARE LAWRENCE School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 5, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 (Email: [email protected]) Summary Some vocal characteristics and call variation in the Australian crows and ravens were studied by sonagraphic analysis of tape-recorded calls. The species grouped according to mean maximum emphasised frequency (Australian Raven Corvus coronoides, Forest Raven C. tasmanicus and Torresian Crow C. orru with lower-freq_uency calls, versus Little Raven C. mellori and Little Crow C. bennetti with higher-frequency calls). The Australian Raven had significantly longer syllables than the other species, but there were no significant interspecific differences in intersyllable length. Calls of Southern C.t. tasmanicus and Northern Forest Ravens C.t. boreus did not differ significantly in any measured character, except for normalised syllable length (phrases with the long terminal note excluded). Northern Forest Ravens had longer normalised syllables than Tasmanian birds; Victorian birds were intermediate. No evidence was found for dialects or regional variation within Tasmania, and calls from the mainland clustered with those from Tasmania. Introduction Owing largely to the definitive work of Rowley (1967, 1970, 1973a, 1974), the diagnostic calls of the Australian crows and ravens Corvus spp. are well known in descriptive terms. The most detailed studies, with sonagraphic analyses, have been on the Australian Raven C. coronoides and Little Raven C. mellori (Rowley 1967; Fletcher 1988; Jurisevic 1999). The calls of the Torresian Crow C. orru and Little Crow C. bennetti have been described (Curry 1978; Debus 1980a, 1982), though without sonagraphic analyses. -

On the Field Characters of Little and Torresian Crows in Central Western Australia. by PETER J

December ] CURRY: Field Characters of Crows 265 1978 (Wheelwright, H. W.) An Old Bushman 1861. Bush Wanderings of a Naturalist. London. Routledge, Warne and Routledge. Whittell, H . M., 1954. The Literature of Australian Birds. Perth. Paterson Brokensha. Wilson, Edward, 1858. On the Introduction of the British Song Bird. Transactions of the Philosophical Institute of Victoria 2, 77-88. Wilson, Edward, 1860. Letter to the Times, 22 September, 1860. (ZOOLOGICAL AND) ACCLIMATISATION SOCIETY OF VICTORIA 1861-1951 Papers (mostly minutes and reports) Vols. 1-13 (Xerox copies in library of Monash University, Clayton, Victoria). 1861-7. Annual reports, Answers to enquiries, report of dinner, rules and objects, etc. (Bound in Victorian pamphlets, nos. 32, 36, 49, 60 and 129 in LaTrobe Library, State Library of Victoria. 1872-8. Proceedings and reports of Annual Meetings, Vols. 1-5. On the Field Characters of Little and Torresian Crows in Central Western Australia. By PETER J. CURRY, 29 Canning Mills Road Kelmscott, W.A., 6111. The Little Crow Corvus bennetti and the Torresian Crow C. orru are evidently sympatric over a large part of northern and cen tral Australia and are notoriously difficult to separate in the field. Over their respective ranges, morphological similarities and indivi dual variation in size are such that some individuals are extremely difficult to identify even in the hand (Rowley, 1970). Despite various recent references which draw attention to the importance of call-notes and habits in field identification (Rowley, 1973; Readers' Digest, 1976), published information on the subject has generally been very brief. The notes which follow r~sult from field observations made in the Wiluna region of central Western Australia, during eighteen months of almost daily contact with both species. -

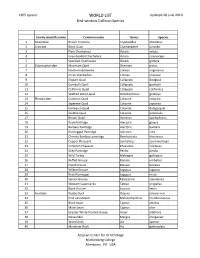

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

BIRDS of YARRAN DHERAN NATURE RESERVE a Guide For

corridor for birds and other wildlife to the Yarra BIRDS OF YARRAN River at Templestowe. The creek provides a reliable Bird walks are held on a monthly basis in DHERAN NATURE source of water and food sources to birds Yarran Dheran. Come and join us! throughout the whole year and supports our RESERVE permanent residents as well as local nomads, Some successful birdwatching tips seasonal visitors and migratory birds who are -if you have binoculars, learn to focus quickly on a A Guide for birdwatchers passing through. distant object Some birds, like Australian Magpie, Grey Fantail, -to help you in bird identification, visit Rainbow Lorikeet, Tawny Frogmouth and Noisy http://ebird.org/australia or http://birdlife.org.au/ Miners are permanent residents. The ponds provide protected areas for nesting and raising chicks for or use a field guide such as Dusky Moorhens and Pacific Black Ducks. Chestnut -Morcombe, Michael, Field Guide to Australian Teal and Wood Ducks are often seen in the creek. Birds, or Regular visitors over spring and summer include the -Graham Pizzey and Frank Knight, Field Guide to the Olive-backed Oriole and Fan-tailed Cuckoo. Birds of Australia The number of species of birds seen in the Reserve A family of four Tawny Frogmouths Both of these publications are also available as has declined over years, due to loss of habitat and phone apps –invaluable for identifying a bird on the Use this guide as a record of the birds you see at climate factors. spot as they include bird calls as well as showing Yarran Dheran. -

Breeding Biology and Behaviour of the Forest Raven Corvus Tasmanicus in Southern Tasmania

Breeding Biology and Behaviour of the Forest Raven Corvus tasmanicus in southern Tasmania Clare Lawrence BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, School of Zoology, University of Tasmania May 2009 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree of diploma by the University or any other institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Clare Lawrence Of. o6 Date Statement of Authority of Access This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968 Clare Lawrence 0/. Date TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 ABSTRACT 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The breeding biology of birds 6 1.2 The Corvids 11 1.3 The Australian Corvids 11 1.4 Corvus tasmanicus 13 1.4.1 Identification 13 1.4.2 Distribution 13 1.4.3 Life history 15 1.4.4 Interspecific comparisons 16 1.4.5 Previous studies 17 1.5 The Forest Raven in Tasmania 18 1.6 Aims 19 2. BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE FOREST RAVEN IN SOUTHERN TASMANIA 21 2.1 Introduction 21 2.2 Methods 23 2.2.1 Study sites 23 2.2.2 Nest characteristics 28 2.2.3 Field observations 31 2.2.4 Parental care 33 2.3 Results 37 2.3.1 Nests 37 2.3.2 Nest success and productivity 42 2.3.3 Breeding season • 46 2.3.4 Parental care 52 2.4 Discussion 66 2.4.1 The nest 68 1 2.4.2 Nest success and productivity 78 2.4.3 Breeding season 82 2.4.4 Parental care 88 2.4.5 Limitations of this study 96 2.5 Conclusion 98 3. -

Assessing the Sustainability of Native Fauna in NSW State of the Catchments 2010

State of the catchments 2010 Native fauna Technical report series Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Assessing the sustainability of native fauna in NSW State of the catchments 2010 Paul Mahon Scott King Clare O’Brien Candida Barclay Philip Gleeson Allen McIlwee Sandra Penman Martin Schulz Office of Environment and Heritage Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Technical report series Native vegetation Native fauna Threatened species Invasive species Riverine ecosystems Groundwater Marine waters Wetlands Estuaries and coastal lakes Soil condition Land management within capability Economic sustainability and social well-being Capacity to manage natural resources © 2011 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage The State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this technical report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to -

The Genera and Species of the Brueelia-Complex (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae) Described by Mey (2017)

Zootaxa 4615 (2): 252–284 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4615.2.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F719B20F-82F0-45FE-976D-9EE55DA05329 The genera and species of the Brueelia-complex (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae) described by Mey (2017) DANIEL R. GUSTAFSSON1,4, SARAH E. BUSH2 & RICARDO L. PALMA3 1Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resource Utilization, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Con- servation and Utilization, Guangdong Institute of Applied Biological Resources, 105 Xingang West Road, Haizhu District, Guangzhou, 510260, China 2School of Biological Sciences, University of Utah, 257 S. 1400 E., Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, USA 3Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand 4Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Two large taxonomic revisions of chewing lice belonging to the Brueelia-complex were published independently in 2017: Gustafsson & Bush (August 2017) and Mey (September 2017). However, Mey (2017) was incorrectly dated “Dezember 2016” on the title page. These two publications described many of the same taxonomic units under different names and therefore, the names in Gustafsson and Bush (2017) have priority over the synonyms in Mey (2017). Here we clarify some of the resulting taxonomic confusion. Firstly, we confirm the availability of the genera Guimaraesiella Eichler, 1949 and Acronirmus Eichler, 1953, as well as the status of Nitzschinirmus Mey & Barker, 2014 as a junior synonym of Guimaraesiella. Nine genera were described and simultaneously placed as juniors synonyms by Mey (2017: 182). -

Lipson Island Baseline Flora and Fauna Report and Assessment of Risk

Donato Environmental Services ABN: 68083 254 015 Mobile: 0417 819 196 Int’l mobile: +61 417 819 196 Email: [email protected] Lipson Island baseline flora and fauna report and assessment of risk Final report to: Golder Associates November 2011 FINAL REPORT Lipson Island baseline flora and fauna report and assessment of risk Disclaimer This report has been prepared and produced by Donato Environmental Services (ABN 68083 254 015) in good faith and in line with the Terms of Engagement between Golder Associates Pty Ltd and Donato Environmental Services. Citation Madden-Hallett, D. M., Hammer, M., Gursansky, W. and Donato, D. B., 2011. Lipson Island baseline flora and fauna report and assessment of risk. For Golder Associates, Donato Environmental Services, Darwin. Table 1. Distribution Receivers Copies Date Issued Contact name Golder Associates Draft report (electronic) 11 July 2011 Rebecca Powlett DES Draft report (electronic) 31 August 2011 Danielle Madden- Hallett Golder Associates Final report (electronic) 16 September 2011Rebecca Powlett DES Electronic comment 26 October 2011 David Donato Golder Associates Final report (electronic) 30 October 2011 Jennifer Boniface DES Electronic comment 1 November 2011 David Donato Golder Associates Final report (electronic) 7 November 2011 Jennifer Boniface ii Lipson Island baseline flora and fauna report and assessment of risk Executive Golder Associates Pty Ltd approached Donato Environmental Services (DES) for a qualitative and quantitative assessment of flora and fauna within the Lipson summary Island Conservation Park, including the intertidal environments. Centrex Metals Ltd (Centrex) has extensive tenement holdings over iron ore resources and exploration targets on Eyre Peninsula in the southern Gawler Craton. -

HOST LIST of AVIAN BROOD PARASITES - 2 - CUCULIFORMES - Old World Cuckoos

Cuckoo hosts - page 1 HOST LIST OF AVIAN BROOD PARASITES - 2 - CUCULIFORMES - Old World cuckoos Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum version 28 Mar 2014 This list remains a working copy; colored text used often as editorial reminder; strike-out gives indication of alternate names. Names prefixed with “&” or “%” usually indicate the host species has successfully reared the brood parasite. Notes following names qualify host status or indicate source for inclusion in list. Important references on all Cuculiformes include Payne 2005 and Erritzøe et al. 2012 (the range maps from Erritzøe et al. 2012 can be accessed at http://www.fullerlab.org/cuckoos/.) Note on taxonomy. Cuckoo taxonomy here follows Payne 2005. Phylogenetic analysis has shown that brood parasitism has evolved in 3 clades within the Cuculiformes with monophyletic groups defined as Cuculinae (including genera Cuculus, Cerococcyx, Chrysococcyx, Cacomantis and Surniculus), Phaenicophaeinae (including nonparasitic genera Phaeniocphaeus and Piaya and the brood parasitic genus Clamator) and Neomorphinae (including parasitic genera Dromococcyx and Tapera and nonparasitic genera Geococcyx, Neomorphus, and Guira) (Aragón et al. 1999). For host species, most English and scientific names come from Sibley and Monroe (1990); taxonomy follows either Sibley and Monroe 1990 or Peterson 2014. Hosts listed at subspecific level indicate that that taxon sometimes considered specifically distinct (see notes in Sibley and Monroe 1990). Clamator Clamator Kaup 1829, Skizzirte Entwicklungs-Geschichte und natüriches System der Europäischen Thierwelt ... , p. 53. Chestnut-winged Cuckoo, Clamator coromandus (Linnaeus 1766) Systema Naturae, ed. 12, p. 171. Distribution. – Southern Asia. Host list. – Based on Friedmann 1964; see also Baker 1942, Erritzøe et al.