Gloria Swanson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Film and Video 1 Audio 3 Printed Material 5 Professional Material 10 Correspondence 13 Financial Material 50 Manuscripts 50 Photographs 51 Personal Memorabilia 65 Scrapbooks 67 Fontaine, Joan #570 Box 1 No Folder I. Film and Video. A. Video cassettes, all VHS format except where noted. In date order. 1. "No More Ladies," 1935; "Tell Me the Truth" [1 tape]. 2. "No More Ladies," 1935; "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937; "Maid's Night Out," 1938; "The Selznick Years," 1969 [1 tape]. 3. "Music for Madam," 1937; "Sky Giant," 1938; "Maid's Night Out," 1938 [1 tape]. 4. "Quality Street," 1937. 5. "A Damsel in Distress," 1937, 2 copies. 6. "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937. 7. "Maid's Night Out," 1938. 8. "The Duke ofWestpoint," 1938. 9. "Gunga Din," 1939, 2 copies. 10. "The Women," 1939, 3 copies [4 tapes; 1 version split over two tapes.] 11. "Rebecca," 1940, 3 copies. 12. "Suspicion," 1941, 4 copies. 13. "This Above All," 1942, 2 copies. 14. "The Constant Nymph," 1943. 15. "Frenchman's Creek," 1944. 16. "Jane Eyre," 1944, 3 copies. 2 Box 1 cont'd. 17. "Ivy," 1947, 2 copies. 18. "You Gotta Stay Happy," 1948. 19. "Kiss the Blood Off of My Hands," 1948. 20. "The Emperor Waltz," 1948. 21. "September Affair," 1950, 3 copies. 22. "Born to be Bad," 1950. 23. "Ivanhoe," 1952, 2 copies. 24. "The Bigamist," 1953, 2 copies. 25. "Decameron Nights," 1952, 2 copies. 26. "Casanova's Big Night," 1954, 2 copies. -

New Releases Watch Jul Series Highlights

SERIES HIGHLIGHTS THE DARK MUSICALS OF ERIC ROHMER’S BOB FOSSE SIX MORAL TALES From 1969-1979, the master choreographer Eric Rohmer made intellectual fi lms on the and dancer Bob Fosse directed three musical canvas of human experience. These are deeply dramas that eschewed the optimism of the felt and considered stories about the lives of Hollywood golden era musicals, fi lms that everyday people, which are captivating in their had deeply infl uenced him. With his own character’s introspection, passion, delusions, feature fi lm work, Fossae embraced a grittier mistakes and grace. His moral tales, a aesthetic, and explore the dark side of artistic collection of fi lms made over a decade between drive and the corrupting power of money the early 1960s and 1970s, elicits one of the and stardom. Fosse’s decidedly grim outlook, most essential human desires, to love and be paired with his brilliance as a director and loved. Bound in myriad other concerns, and choreographer, lent a strange beauty and ultimately, choices, the essential is never so mystery to his marvelous dark musicals. simple. Endlessly infl uential on the fi lmmakers austinfi lm.org austinfi 512.322.0145 78723 TX Austin, Street 51 1901 East This series includes SWEET CHARITY, This series includes SUZANNE’S CAREER, that followed him, Rohmer is a fi lmmaker to CABARET, and ALL THAT JAZZ. THE BAKERY GIRL OF MONCEAU, THE discover and return to over and over again. COLLECTIONEUSE, MY NIGHT AT MAUD’S, CLAIRE’S KNEE, and LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON. CINEMA SÉANCE ESSENTIAL CINEMA: Filmmakers have long recognized that cinema BETTE & JOAN is a doorway to the metaphysical, and that the Though they shared a profession and were immersive nature of the medium can bring us contemporaries, Bette Davis and Joan closer to the spiritual realm. -

Pilot Season

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Spring 2014 Pilot Season Kelly Cousineau Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cousineau, Kelly, "Pilot Season" (2014). University Honors Theses. Paper 43. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pilot Season by Kelly Cousineau An undergraduate honorsrequirements thesis submitted for the degree in partial of fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Film Thesis Adviser William Tate Portland State University 2014 Abstract In the 1930s, two historical figures pioneered the cinematic movement into color technology and theory: Technicolor CEO Herbert Kalmus and Color Director Natalie Kalmus. Through strict licensing policies and creative branding, the husband-and-wife duo led Technicolor in the aesthetic revolution of colorizing Hollywood. However, Technicolor's enormous success, beginning in 1938 with The Wizard of Oz, followed decades of duress on the company. Studios had been reluctant to adopt color due to its high costs and Natalie's commanding presence on set represented a threat to those within the industry who demanded creative license. The discrimination that Natalie faced, while undoubtedly linked to her gender, was more systemically linked to her symbolic representation of Technicolor itself and its transformation of the industry from one based on black-and-white photography to a highly sanctioned world of color photography. -

Leituras Freudianas E Lacanianas Do Espaço Simbólico Hitchcock's Films O

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas Ano 2017 Mark William Poole Os Filmes de Hitchcock no Sofá: Leituras Freudianas e Lacanianas do Espaço Simbólico Hitchcock’s Films on the Couch: Freudian and Lacanian Readings of Symbolic Space Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas Ano 2017 Mark William Poole Os Filmes de Hitchcock no Sofá: Leituras Freudianas e Lacanianas do Espaço Simbólico Hitchcock’s Films on the Couch: Freudian and Lacanian Readings of Symbolic Space Tese apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Estudos Culturais, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro o júri Doutor Carlos Manuel da Rocha Borges de Azevedo, Professor Catedrático, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade do Porto. Doutor Mário Carlos Fernandes Avelar, Professor Catedrático, Universidade Aberta, Lisboa. Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado, Universidade de Aveiro (orientador). Doutor Kenneth David Callahan, Professor Associado, Universidade de Aveiro. Doutor Nelson Troca Zagalo, Professor Auxiliar, Universidade do Minho. presidente Doutor Nuno Miguel Gonçalves Borges de Carvalho, Reitor da Universidade de Aveiro. agradecimentos Primarily, I would like to thank Isabel Pereira, without whose generosity this entire process would not have been possible. She believes in supporting all types of education and I cannot express my gratitude enough. I express equal gratitude to Marta Correia, who has been the Alma Reville of this thesis. She has had the patience to listen to my ideas and offer her invaluable insights, while proofreading and criticising the chapters as this thesis evolved. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

In 1925, Eight Actors Were Dedicated to a Dream. Expatriated from Their Broadway Haunts by Constant Film Commitments, They Wante

In 1925, eight actors were dedicated to a dream. Expatriated from their Broadway haunts by constant film commitments, they wanted to form a club here in Hollywood; a private place of rendezvous, where they could fraternize at any time. Their first organizational powwow was held at the home of Robert Edeson on April 19th. ”This shall be a theatrical club of love, loy- alty, and laughter!” finalized Edeson. Then, proposing a toast, he declared, “To the Masquers! We Laugh to Win!” Table of Contents Masquers Creed and Oath Our Mission Statement Fast Facts About Our History and Culture Our Presidents Throughout History The Masquers “Who’s Who” 1925: The Year Of Our Birth Contact Details T he Masquers Creed T he Masquers Oath I swear by Thespis; by WELCOME! THRICE WELCOME, ALL- Dionysus and the triumph of life over death; Behind these curtains, tightly drawn, By Aeschylus and the Trilogy of the Drama; Are Brother Masquers, tried and true, By the poetic power of Sophocles; by the romance of Who have labored diligently, to bring to you Euripedes; A Night of Mirth-and Mirth ‘twill be, By all the Gods and Goddesses of the Theatre, that I will But, mark you well, although no text we preach, keep this oath and stipulation: A little lesson, well defined, respectfully, we’d teach. The lesson is this: Throughout this Life, To reckon those who taught me my art equally dear to me as No matter what befall- my parents; to share with them my substance and to comfort The best thing in this troubled world them in adversity. -

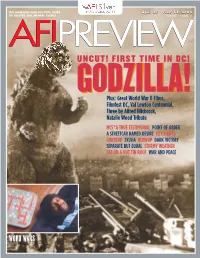

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

Ghp Stopl (Sazrtfr Att& (Eolontat Hatlg

^PPip «^p -• fflSle GHp Stopl (Sazrtfr att& (Eolontat Hatlg INCORPORATING THE ROYAL GAZETTE (Etffcblished 1828) and THE BERMUDA COLONIST (Established 1866) VOL. 15~~NO. 231 HAMILTON. BERMUDA, WEDNESDAY, OCOTBER 1, 1930 3D PER COPY—AOl- PER ANNUM ENGLAND MOURNS LOSS OF BRIIXIANT IAWYER^STATEMAN PREMIERS GATHER FOR DEATH OF LORD THE BERMUDA NEW YOK STOCK [ THEY SAY fl BIRKENHEAD RAILWAY MARKET That the expected flight of the Do-X IMPERIAL CONFERENCE is creating quite a lot of interest. Rapid Progress Expected * » * Brilliant Statesman, That it should mark an era ln de Hfr~ Yesterday's Closing velopment. Shortly * * * Lawyer and Writer Prices That proper recognition of the event Germany Faced With Big in consequence of a cable des should be made. patch received by us yesterday to * * * A special Reuter's despatch re the effeot-teat a railway construct Alleghany Oorp -„-„..- 18 That some will regret a foreign ion expert-.had sailed -by the Lady r Deficit ceived by the Royal Gazette and Allied Chemical. __. N.Q. firm is first in the field. Colonist Daily yesterday announced Somers to start construction on * * * Bermuda's first railway, our re Am. Oan 117 the death of Lord Birkenhead whose Am. ft Foreign Power 53) That nevertheless the first should health has been giving consider presentee called on Mr. O. A. always receive credit. Jones, the construction manager Am. Locomotive. 37} able anxiety for some time. Few Am. Power & Light... 70 * • • men of the present age have had a for Messrs Balfour, Beatty, & Com pany, **tho are building the railway. Am. Smelting & Refining. -

The Swedish Film and Post-War American Films 1938

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 14 WEST 49TH STREET, NEW YORK TEUEPHONE: CIRCLE 7-7470 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Legends to the contrary notwithstanding, the negative of Erich von Stroheim's much-discussed film, Greed, has been preserved in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's vaults and it has therefore been possible to include this celebrated "masterpiece of realism" in the Museum of Modern Art Film Libraryfs current Series IV, The Swedish Film and Post-War American Films, Greed will be shown to Museum members on Wednesday, February 23rd, at 8:45 P.M. in the auditorium of the American Museum of Natural History, 77th Street and Central Park West. Thereafter it will be available to students of the film in i colleges and museums throughout the country. Greed, a faithful transcription into pictorial terms of Frank Norris1 novel, "McTeague," was created under unusual circumstances and met with a curious fate. It was not made in a studio, but on location in San Francisco. Whole blocks and houses were purchased as settings , walls knocked out to make the photography of real in teriors practicable. Every detail of the novel was reproduced at considerable expense of time and money, with a passionate and un compromising care for veracity. Eventually von Stroheim offered his producers his finished work, a final cut print twenty reels long which he proposed they should issue in two parts, and which bore no perceptible trace of those elements usually reckoned as "box office. The film was taken from him, cut down to the present ten reel ver sion and so released. -

Erich Von Stroheim, the Child of His Own Loins Fanny Lignon

Erich von Stroheim, the child of his own loins Fanny Lignon To cite this version: Fanny Lignon. Erich von Stroheim, the child of his own loins. 2017. hal-01638172 HAL Id: hal-01638172 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01638172 Submitted on 19 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. http://www.thalim.cnrs.fr/ http://www.univ-lyon1.fr/ Fanny Lignon Maître de conférences Etudes cinématographiques et audiovisuelles Université Lyon 1 Laboratoire THALIM / Equipe ARIAS (CNRS / Paris 3 / ENS) E-mail : [email protected] LIGNON Fanny, « Erich von Stroheim, the child of his own loins », OUPblog, Oxford University Press, 22 septembre 2017. [En ligne : https://blog.oup.com/2017/09/erich-von-stroheim-child-loins/] ERICH VON STROHEIM, THE CHILD OF HIS OWN LOINS Fanny Lignon (Translated by Civan Gürel) Even though Erich von Stroheim passed away 60 years ago, it is clear that his persona is still very much alive. His silhouette and his name are enough to evoke an emblematic figure that is at once Teutonic, aristocratic and military. No one has forgotten his timeless characters—among others, Max von Mayerling in Sunset Boulevard, a talented film director who has become the devoted servant of the almost-forgotten silent film star whose movies he used to make, or von Rauffenstein, the prisoner of war camp commandant of La Grande Illusion with his neck stiff in a brace, perfectly symbolizing at once a world that is gradually passing away and a world that is being born.