Folklore: the Eerie Underbelly of British 1970S Folk-Horror Television?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Marble Hornets, the Slender Man, and The

DIGITAL FOLKLORE: MARBLE HORNETS, THE SLENDER MAN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF FOLK HORROR IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Dana Keller B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Dana Keller, 2013 Abstract In June 2009 a group of forum-goers on the popular culture website, Something Awful, created a monster called the Slender Man. Inhumanly tall, pale, black-clad, and with the power to control minds, the Slender Man references many classic, canonical horror monsters while simultaneously expressing an acute anxiety about the contemporary digital context that birthed him. This anxiety is apparent in the collective legends that have risen around the Slender Man since 2009, but it figures particularly strongly in the Web series Marble Hornets (Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage June 2009 - ). This thesis examines Marble Hornets as an example of an emerging trend in digital, online cinema that it defines as “folk horror”: a subgenre of horror that is produced by online communities of everyday people— or folk—as opposed to professional crews working within the film industry. Works of folk horror address the questions and anxieties of our current, digital age by reflecting the changing roles and behaviours of the everyday person, who is becoming increasingly involved with the products of popular culture. After providing a context for understanding folk horror, this thesis analyzes Marble Hornets through the lens of folkloric narrative structures such as legends and folktales, and vernacular modes of filmmaking such as cinéma direct and found footage horror. -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

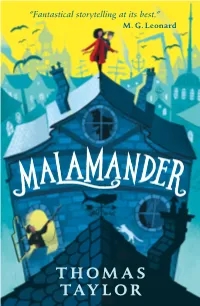

Malamander-Extract.Pdf

“Fantastical storytelling at its best.” M. G. Leonard THOMAS TAYLOR THOMAS TAYLOR This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. First published 2019 by Walker Books Ltd 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Text and interior illustrations © 2019 Thomas Taylor Cover illustrations © 2019 George Ermos The right of Thomas Taylor to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book has been typeset in Stempel Schneider Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4063-8628-8 (Trade) ISBN 978-1-4063-9302-6 (Export) ISBN 978-1-4063-9303-3 (Exclusive) www.walker.co.uk Eerie-on-Sea YOU’VE PROBABLY BEEN TO EERIE-ON-SEA, without ever knowing it. When you came, it would have been summer. -

Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 Pm

1 Wednesday, March 18, 2020 2:30 p.m. - 3:15 p.m. Pre-Opening Refreshment Ballroom Foyer ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 3:30 p.m. - 4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Ballroom Host: Jeri Zulli, Conference Director Welcome from the President: Dale Knickerbocker Guest of Honor Reading: Jeff VanderMeer Ballroom “DEAD ALIVE: Astronauts versus Hummingbirds versus Giant Marmots” Host: Benjamin J. Robertson University of Colorado, Boulder ********** Wednesday, March 18, 2020 4:30 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 1. (GaH) Cosmic Horror, Existential Dread, and the Limits of Mortality Belle Isle Chair: Jude Wright Peru State College Dead Cthulhu Waits Dreaming of Corn in June: Intersections Between Folk Horror and Cosmic Horror Doug Ford State College of Florida The Immortal Existential Crisis Illuminates The Monstrous Human in Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf Jordan Moran State College of Florida Hell . With a Beach: Christian Horror in Michael Bishop's "The Door Gunner" Joe Sanders Shadetree Scholar 2 2. (CYA/FTV) Superhero Surprise! Gender Constructions in Marvel, SpecFic, and DC Captiva A Chair: Emily Midkiff Northeastern State University "Every Woman Has a Crazy Side"? The Young Adult and Middle Grade Feminist Reclamation of Harley Quinn Anastasia Salter University of Central Florida An Elaborate Contraption: Pervasive Games as Mechanisms of Control in Ernest Cline's Ready Player One Jack Murray University of Central Florida 3. (FTFN/CYA) Orienting Oneself with Fairy Stories Captiva B Chair: Jennifer Eastman Attebery Idaho State University Fairy-Tale Socialization and the Many Lands of Oz Jill Terry Rudy Brigham Young University From Android to Human – Examining Technology to Explore Identity and Humanity in The Lunar Chronicles Hannah Mummert University of Southern Mississippi The Gentry and The Little People: Resolving the Conflicting Legacy of Fairy Fiction Savannah Hughes University of Maine, Stonecoast 3 4. -

NVS 10-1 Announcements Page;

Announcements: CFPs, conference notices, & current & forthcoming projects and publications of interest to neo-Victorian scholars (compiled by the NVS Editorial Team) ***** CFPs: Journals, Special Issues & Collections (Entries that are only listed, without full details, were highlighted in a previous issue of NVS. Entries are listed in order of abstract/submission deadlines.) In Frankenstein’s Wake Special Issue of The International Review of Science Fiction (2018) Submissions due: 29 January 2018. Articles should be approximately 6,000 words long and written in accordance with the style sheet available at the SF Foundation website and submitted to journaleditor@sf- foundation.org. Journal website: https://www.sf- foundation.org/publications/foundation/index.html Dickens and Wills; Engaging Dickens; Obscure or Under-read Dickens 3 Special Issues of Dickens Quarterly Submissions due: 1 September 2018. Please submit articles in two forms: an electronic version to [email protected] and a hard copy to the journal’s address: 100 Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 7NE England. Essays should range between 6,000 and 8,000 words, although shorter submissions will be considered. For further instructions, see ‘Dickens Quarterly: A Guide for Contributors’, available as a PDF file from the website of the Dickens Society dickenssociety.org. Journal Website: https://www.press.jhu.edu/journals/dickens-quarterly Neo-Victorian Studies 10:1 (2017) pp. 193-200 194 Announcements _____________________________________________________________ Perspectives on the Non-Human in Literature and Culture (Routledge) Submissions due: no deadline. Please address any questions about this series or the submission process to Karen Raber at [email protected]. Series website: https://www.routledge.com/Perspectives-on-the-Non- Human-in-Literature-and-Culture/book-series/PNHLC Journal of Historical Fictions Submissions due: no deadline. -

Since I Began Reading the Work of Steve Ditko I Wanted to Have a Checklist So I Could Catalogue the Books I Had Read but Most Im

Since I began reading the work of Steve Ditko I wanted to have a checklist so I could catalogue the books I had read but most importantly see what other original works by the illustrator I can find and enjoy. With the help of Brian Franczak’s vast Steve Ditko compendium, Ditko-fever.com, I compiled the following check-list that could be shared, printed, built-on and probably corrected so that the fan’s, whom his work means the most, can have a simple quick reference where they can quickly build their reading list and knowledge of the artist. It has deliberately been simplified with no cover art and information to the contents of the issue. It was my intension with this check-list to be used in accompaniment with ditko-fever.com so more information on each publication can be sought when needed or if you get curious! The checklist only contains the issues where original art is first seen and printed. No reprints, no messing about. All issues in the check-list are original and contain original Steve Ditko illustrations! Although Steve Ditko did many interviews and responded in letters to many fanzines these were not included because the checklist is on the art (or illustration) of Steve Ditko not his responses to it. I hope you get some use out of this check-list! If you think I have missed anything out, made an error, or should consider adding something visit then email me at ditkocultist.com One more thing… share this, and spread the art of Steve Ditko! Regards, R.S. -

Emma Scott Make-Up & Hair Designer

Lux Artists Ltd. 12 Stephen Mews London W1T 1AH +44 (0)20 7637 9064 www.luxartists.net EMMA SCOTT MAKE-UP & HAIR DESIGNER FILM/TELEVISION DIRECTOR PRODUCER POSSUM Matthew Holness The Fyzz Cast: Sean Harris THE SNOWMAN Tomas Alfredson Working Title Cast: Michael Fassbender, Rebecca Ferguson, Charlotte Gainsbourg Universal Pictures FREE FIRE Ben Wheatley Rook Films Cast: Sam Riley, Cillian Murphy, Brie Larson, Noah Taylor, Armie Hammer Studio Canal Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2016) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2016) Nominated, Best Director, BIFA (2016) PRIDE, PREJUDICE & ZOMBIES Burr Steers Cross Creek Pictures Cast: Sam Riley, Matt Smith, Lena Headey, Jack Huston, Douglas Booth BABYLON (Pilot) Danny Boyle Nightjack Cast: Brit Marling, James Nesbitt Channel 4 THE GOOB Guy Myhill BBC Films Cast: Sean Harris, Hannah Spearritt, Liam Walpole Winner, Golden Hitchcock Award, Dinard British Film Festival (2014) ’71 Yann Demange Warp Films Cast: Sean Harris, Jack O’Connell, Paul Anderson, Sam Reid Nominated, Outstanding British Film, BAFTA Awards (2015) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2014) Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2014) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2014) MUPPETS: MOST WANTED James Bobin Walt Disney Pictures Cast: Ricky Gervais, Tina Fey, Ty Burrell SOUTHCLIFFE (Mini-series) Sean Durkin Warp Films Cast: Sean Harris, Rory Kinnear, Shirley Henderson, Eddie Marsan, Joe Dempsie Nominated, Best Mini-Series, BAFTA TV Awards (2014) UTOPIA (Season 1) Marc Munden Kudos Film & TV Cast: -

Wfs Filmnotes Template

30 April 2013 www.winchesterfilmsociety.co.uk … why not visit our website to join in the discussion after each screening? Sightseers UK 2012 Every season when the committee Ben Wheatley is the outstanding young whittle down a long, long list to just British film-maker who got himself Directed by 16 films, there are one or two that talked about with his smart debut Down Ben Wheatley really intrigue us and we can’t wait to Terrace; then he scared the daylights out Director of Photography see. Sightseers is that film for 12/13! of everyone, as well as amusing and Laurie Rose baffling them, with his inspired and There is no direct French translation for ambiguous chiller Kill List. His talent Original Music and signature are vividly present in every Jim Williams the word ‘sightseers’, so Ben Wheatley’s new film is titled Touristes in Cannes, frame of this new movie, Sightseers, a Screenplay where it has screened as part of grisly and Ortonesque black comedy Alice Lowe Directors’ Fortnight. In a way, that’s about a lonely couple played by co- Steve Oram perfectly fitting: this flesh-creepingly writers Steve Oram and Alice Lowe. funny comedy turns into something that, Again, Wheatley is adept at summoning Cast rather worryingly, you can’t imagine an eerie atmosphere of Wicker Man Alice Lowe happening in any other country but disquiet; the glorious natural Tina England. Lowe and Oram’s script surroundings are endowed with a golden Steve Oram balances nimbly on the thread of razor sunlit glow and the trips to quaint Chris wire between horror and farce: the film venues of local interest are well Eileen Davies is frequently laugh-out-loud funny but observed: particularly Tina's heartbroken Carol the couple’s crimes are never trivialised, solo excursion to the Pencil Museum. -

SCB Distributors Spring 2013 Catalog

SCB DISTRIBUTORS SPRING 2013 SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT SCB DISTRIBUTORS IS Birch Bench Press PROUD TO INTRODUCE Bongout Cassowary Press Coffee Table Comics Déjà vu Lifestyle Creations Grapevine Press Honest Publishing Penny-Ante Editions SCB: TRULY INDEPENDENT The cover image is from page 113 of The Swan, published by Merlin Unwin, found on page 83 of this catalog. Catalog layout by Dan Nolte, based on an original design by Rama Crouch-Wong My First Kafka Runaways, Rodents, & Giant Bugs By Matthue Roth Illustrated by Rohan Daniel Eason “Matthue Roth is the kind of person you move to San Francisco to meet.” – Kirk Read, How I Learned to Snap An adaptation of 3 Kafka stories into startling, creepy, fun stories for all ages, featuring: ■ runaway children who meet up with monsters ■ a giant talking bug ■ a secret world of mouse-people This subversive debut takes a place alongside Sendak, Gorey, and Lemony Snicket. ■ endorsed by Neil Gaiman Matthue Roth wrote Yom Kippur a Go-Go and Never Mind the Goldbergs, nominated as an ALA Best Book and named a Best Book by the NY Public Library. He produced the animated series G-dcast, and wrote the feature film 1/20. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the chef KAFKA, REIMAGINED AND ILLUSTRATED Itta Roth. www.matthue.com Rohan Daniel Eason, who studied painting in London, illustrated Anna and the Witch's Bottle and Tancredi. My First Kafka ISBN: 978-1-935548-25-6 $18.95 | hardcover 8 x 10 32 pages 32 B&W Illustrations Ages 7 & Up June Children’s Picture Book Literature ONE PEACE BOOKS SCB DISTRIBUTORS..|..SPRING 2013..|..1 Terminal Atrocity Zone: Ballard J.G. -

Film Reviews

Page 78 FILM REVIEWS Kill List (Dir. Ben Wheatley) UK 2011 Optimum Releasing Note: This review contains extensive spoilers Kill List is the best British horror film since The Descent (Dir. Neil Marshall, 2005). Mind you, you wouldn’t know that from the opening halfhour or so. Although it opens with an eerie scratching noise and the sight of a cryptic rune that can’t help but evoke the unnerving stick figure from The Blair Witch Project (Dir. Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999), we’re then plunged straight into a series of compellingly naturalistic scenes of domestic discord which, as several other reviews have rightly pointed out, evoke nothing so much as the films of Mike Leigh. (The fact that much of the film’s dialogue is supplied by the cast also adds to this feeling.) But what Leigh’s work doesn’t have is the sense of claustrophobic dread that simmers in the background throughout Wheatley’s film (his second, after 2009’s Down Terrace ). Nor have any of them – to date at least – had an ending as devastating and intriguing as this. Yet the preliminary scenes in Kill List are in no sense meant to misdirect, or wrongfoot the audience: rather, they’re absolutely pivotal to the narrative as a whole, even if many of the questions it raises remain tantalisingly unresolved. Jay (Neil Maskell) and his wife Shel (MyAnna Buring) live in a spacious, wellappointed suburban home (complete with jacuzzi) and have a sweet little boy, but theirs is clearly a marriage on the rocks, and even the most seemingly innocuous exchange between them is charged with hostility and mutual misunderstanding. -

Title FX Volume 2

Title FX Vol. 2 Title fx vol 2 Disc Track Index Secs Description Filename Category TFX2-01 1 1 7.4 Digital Pulse Alarm Scan Warning DigitalPulseAlarmSc TFX2001 Computers & Beeps TFX2-01 2 1 4.1 Low Heavy Text Materialize Sweep LowHvyTextMateriali TFX2002 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 3 1 3.3 Heavy Text Sliding Into Shifted Rumble Short HvyTextSlidingShift TFX2003 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 4 1 4.1 Sliding Pitch Motor By SlidingPitchMotorBy TFX2004 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 5 1 6.9 Slide Multi Whoosh Phase Pitch Looped SlideMultiWhooshPha TFX2005 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 6 1 6.5 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycles SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2006 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 7 1 6.1 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycle Slow Pitch SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2007 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 8 1 1.4 Low Rumble Transition LowRumbleTransition TFX2008 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 9 1 2.5 Fast Text Fade Into Low Rumble Transition FstTextFadeLowRumbl TFX2009 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 10 1 2.6 Warp Tone Modulated Fade In WarpToneModulatedFa TFX2010 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 11 1 5.9 Future Mechanical Slow By FutureMechanicalSlw TFX2011 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 12 1 2.7 Heavy Mechanical Fly Transitional By Short HvyMechanicalFlyTra TFX2012 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 13 1 2.6 Mechanical Fly By Whoosh MechanicalFlyByWhoo TFX2013 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 14 1 4.1 Mechanical Fly By Modulated Slow Pitch Descending Transition MechanicalFlyByModu TFX2014 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 15 1 7.2 Mechanical Fly By Modulated