Living Bridges Using Aerial Roots of Ficus Elastica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature-Based Infrastructure Solutions for Extreme Climate

Living Root Bridge Ecosystems of Meghalaya, India: Nature-based Infrastructure Solutions for Extreme Climate By Sanjeev Shankar Published in PEDRR (Ecosystems for Disaster Risk Reduction and Adaptation) Newsletter 2020 Article adapted from original article published in Design with Life: Biotech Architecture and Resilient Cities by Maria Aiolova and Mitchell Joachim Figure 1. Double tier Living root bridge, Nongriat village, Meghalaya (2013) Current research and discourse surrounding integration of natural - living systems within infrastructure and buildings is often perceived as speculative, niche and avant garde. While this outlook has many underpinnings, the case study of ‘Ficus-based living root bridges of Meghalaya’ can provide rare real life practical evidence in support of this field, and inspire the global community to re-imagine the ‘built’ environment as a living-nourishing environment. Living Root Bridge Ecosystems are Ficus elastica1-based infrastructure and landscape solutions within dense sub tropical moist broadleaf forest ecoregions of North Eastern Indian Himalayas (25° 30’N and 91° 00’E). As living plant-based structural ecosystems, these infrastructure solutions are grown and nurtured by indigenous Khasi and Jaintia tribes of Meghalaya over decades and perform as critical rural connectivity and landscape solutions for several centuries in extreme climatic conditions2. With 1) low material and maintenance cost, 2) high robustness and longevity, 3) progressive increase in strength and performance, 4) community-led participatory design approach across multiple generations, 5) remedial impact on surrounding soil, water and air, 6) support for other plant and animal systems, 7) keystone role of Ficus plant species in local ecology, and 8) diverse morphologies including bridges, ladders, towers, viewing platforms and soil erosion/landslide prevention structures, Ficus-based living root structural ecosystems offer a compelling model for socio-ecological resilience and living plant-based sustainable infrastructure solutions. -

Recent Developments in Uranium Resources and Supply Was Held in Vienna from 24 to 26 May 1993

IAEA-TECDOC-823 Recent developmentsin uranium resources and supply Proceedings of a Technical Committee meeting held Vienna,in 24-28 1993May INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY /A\ IAEe Th A doe t normallsno y maintain stock f reportso thin si s series. However, microfiche copie f thesso e reportobtainee b n sca d from INIS Clearinghouse International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramerstrasse5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria Orders should be accompanied by prepayment of Austrian Schillings 100,- for forchequa the m the IAEm of in of in eAor microfiche service coupons which may be ordered separately from the INIS Clearinghouse. The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Nuclear Material Fued san l Cycle Technology Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramerstrasse5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN URANIUM RESOUCES AND SUPPLY IAEA, VIENNA, 1995 IAEA-TECDOC-823 ISSN 1011-4289 © IAEA, 1995 Printed by the IAEA in Austria September 1995 FOREWORD While the IAEA's projections of the growth of nuclear power remain a modest 1.5% per year through 2010, uranium continues to be an important source of energy. In January 1993 there were nuclea4 42 r power plant operation si n wit hcombinea d electricity generating capacit G(e)1 33 f .yo In 1992 these plants generated over 2027 TW.h electricity, equivalent to nearly 17% of the total. To achieve this, 57 200 tonnes uranium were required as nuclear fuel. Historically, nuclear fuel activities were primarily segregate mutuallo tw n di y exclusive areas consisting of WOCA (world outside centrally planned economy areas) and non-WOCA. -

Meghalaya 7 Days and 6 Nights Itinerary - Shillong, Mawlongbna, Cherrapunji, Nongriat, Shnongpdeng, Krangsuri

Meghalaya 7 days and 6 nights Itinerary - Shillong, Mawlongbna, Cherrapunji, Nongriat, Shnongpdeng, Krangsuri Day 01: Arrival at Shillong (Guwahati – Shillong: 110km) Itinerary: ▪ Your transport will pick you up from Guwahati airport and transport you to Shillong. ▪ On arrival check in to your residence. ▪ If there is enough daylight and if you are up for it, you can head out and explore Shillong. ▪ Dinner at the residence. Day 02: Explore Shillong, East Khasi Hills Highlights: Use the day for exploring the local Shillong town and the popular sites near Shillong. Elephant falls is a dramatic, multi-tiered waterfall in a picturesque surrounding, with an easy walking trail and stairs. Head to the peak of Shillong for a majestic view of the capital after which you can visit the Air Force Museum, a great place to get knowledge about the country’s defence forces, mainly the Indian Air Force, brave flying warriors and defence history, that displays uniforms worn by the air force pilots, missiles, rockets and miniature models of air-crafts. Itinerary: ▪ Breakfast at the residence ▪ Use the day to explore Shillong town. ▪ Try Cafe Shillong for lunch. ▪ Ride to Elephant falls, Shillong Peak and Air Force Museum. ▪ Dinner at the residence ▪ Rest for the night. Day 03: Day trip to Mawlongbna, East Khasi Hills (Shillong – Mawlongbna: 79 km) Highlights: Use the day to explore Mawlongbna, the Traveller’s Nest. Indulge in some adventurous activities such as canyoning, swimming, kayaking and zip lining, which are famous at this venue. A short- guided walk to the west of the area where the fossils are found, takes you unsuspectingly into a land where legend and folklore come alive. -

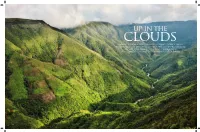

Up in the Clouds Far Away in the Northeastern Hills Lies a Land Largely Ignored by Everyone but Meteorologists, Adventurers And, Oh Yes, Hardcore Rockers

up in the clouds Far away in the northeastern hills lies a land largely ignored by everyone but meteorologists, adventurers and, oh yes, hardcore rockers. Vivek Menezes explains why Meghalaya is India’s coolest new frontier. Photographs by Tom Parker !"# !"$ ‘He who has not trodden the rock bottom of these precipices can never claim he really knows his land’ —KYNPHAM SING NONGKYNRIH, KHASI POET hen the mist cleared at with geraniums and anthuriums and These are Meghalaya’s Khasi hills, Wdaybreak, I lost my heart to Laitkynsew. rows and rows of potted orchids. which came under British control after Nothing could be seen when we Enormous, slow-moving butter"ies a brutal three-year war, and were soon arrived the night before, nosing slowly wobbled through the clear morning rolled into colonial Assam along with through the murk. But sunrise revealed air. Soon, the mossy paths !lled the adjacent Garo and Jaintia hills (as we were poised on the knife-edge of with red-cheeked children in bright well as present-day Nagaland, Mizoram a breathtakingly narrow ridge. Far cardigans and matching tartan kilts, as and Arunachal Pradesh). This culturally below us, on one side, the waterlogged though they had walked out of a fairy distinct region was renamed Meghalaya plains of Bangladesh reached pale to tale. Then, a group of young mothers, when it became India’s 21st state in the horizon. On the other side, steep wearing shawls clasped at the shoulder 1972. The poetically named ‘abode of jungle gorges receded into the distance, and falling to their ankles, looked up to the clouds’ (in Sanskrit) is one part of studded with waterfalls that gushed us, agape, and chorused “Khublei!” the North-East where travel is now into the void. -

Chalohoppo-With-Muzart-To-An-Emerald-Meghalaya-A-Musical-Village.Pdf

ChaloHoppo with MuzArt to an Emerald Meghalaya & a Musical Village December 13 - 18 Music and Art Therapy sessions in the Emerald Meghalaya Travel and art have always been the best of pals! Travel to the emerald waters of Meghalaya, through the Double-Decker Living Root Bridge and a whistling village. Heal yourself, with live Music and Art Therapy sessions. A special hand-picked trip for the lovers of art and music. A hanging bridge on the trek to Nongriat village in Cherrapunjee Travelling, Music and Art -The universal healers. If you also believe in the same and would love these three meet up, this especially crafted trip is for you! Join us with MuzArt, two trained therapists from Mumbai helping you dive into the ocean of relaxation through music and art. Every day comes with a theme-based session, conducted to make peace with stress, expression and self-awareness. Meditate to the sound of music and the strokes of paint in the secluded natural spots. This winter let music and art be your guide. The brief Itinerary 5 nights and 6 days Day 1 The magic in everyone Your trip starts at Guwahati airport at 8:30 am. Travel from the plains of Assam to the hills of Meghalaya. Make your way straight to the Liatlum Canyons. Capture the clouds settling in the surreal valley. You will then head to Shillong. Post lunch and settling in your abode, make your way to Dylan's Cafe. The first session here will be about simple games and activities involving dry art media and instruments. -

Current Affairs January 2020

VISION IAS www.visionias.in CURRENT AFFAIRS JANUARY 2020 Copyright © by Vision IAS All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of Vision IAS. 1 www.visionias.in ©Vision IAS Table of Contents 1. POLITY & GOVERNANCE _______________ 4 4.2. Pact to end Bru Refugee Crisis __________ 42 1.1. Article 131 of Indian Constitution ________ 4 4.3. Kuki- Naga Militants Sign Pact __________ 43 1.2. Office of the Speaker and the Issue of 4.4. Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre _ 44 Defection _______________________________ 5 5. ENVIRONMENT ______________________ 46 1.3. SC’s Verdicts on Curbing Restrictions _____ 7 5.1. Green Economy _____________________ 46 1.4. Aadhar report ________________________ 9 5.2. Coral Restoration ____________________ 48 1.5. Enemy Properties ____________________ 10 5.3. Guidelines for Implementing Wetlands 1.6. Regulating Minority Educational Institutions (Conservation and Management) Rules, 2017 _ 50 ______________________________________ 11 5.4. 10 New Ramsar Sites in India __________ 52 1.7. EWS Quota in States _________________ 13 5.5. Urban Lakes ________________________ 54 1.8. All India Judicial Services ______________ 14 5.6. Compensatory Afforestation: Green Credit 1.9. Fast Track Special Courts ______________ 15 Scheme _______________________________ 55 2. INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS __________ 17 5.7. African Cheetah _____________________ 56 2.1. New and Emerging Strategic Technologies 5.8. State Energy Efficiency Preparedness Index Division _______________________________ 17 2019 __________________________________ 57 2.2. South China Sea _____________________ 18 5.9. -

Walking Over Living Root Bridges

ChaloHoppo to a Wet & Wild Meghalaya Time you get to explore a Wet and Wild Meghalaya! If you grew up in these villages of Meghalaya, you would never need an amusement park in your life. From serene spots in the jungle to exciting river activities and picturesque lakes, they have it all. Go find a pair of swimming trunks! A hanging bridge on the trek to Nongriat village in Cherrapunjee With abundant activities like river canyoning, kayaking, zip lining and lots of swimming, this trip is meant for those with an adventurous spirit. A trek that takes you right to the heart of the living root bridges where you live amidst nature’s wonder and then move to challenge the waterfalls of a Khasi village as you trek along its course while jumping, sliding and scrambling. There will be more relaxed times like when you kayak over still waters and enjoy nature walks and camp around a bonfire. A glimpse of what the river canyoning looks like! The brief Itinerary 6 nights and 7 days Day 1 Welcome to an authentic Meghalayan village Mawphanlur can be described as the most multi-dimensional place for leisure seekers. It just engulfs you in all its simplicity. The minimalism of the place with three simple cottages, one kitchen area and dining set up is a perfect example of letting nature do what it does best, mesmerise people. They have also thrown in a few kayaks and pedal boats in one of the many ponds where family, friends and even enemies can relax and chill over still waters. -

Tour Itinerary: Day 01: Drive to Cherrapunjee, Sightseeing in Cherrapunjee

Tour de India HOLIDAYS Beautiful Meghalaya ‘Adventure, Camp, Trek, WaterFalls – The Abode of Clouds’ Group Tour Promotion About Meghalaya Meghalaya, ‘Abode of Clouds’, is known for its serenity and tranquillity. A major section of the state consists of dense forests which preserves the vast biodiversity of region. The lush green state, encompassing the Garo, Khasi and Jaintia hills, offers ample opportunity of great treks and walks... Weather and Climate Planning Meghalaya holiday in summer offers an ideal escape from the scorching heat. The temperature in many parts of the state never goes beyond 28°C. Mornings are as pleasant as evenings. Many regional festivals are also conducted during the months of April to June. Thus, summer is the best season to visit Meghalaya. Shopping in Meghalaya Majority of the population of this state consists of tribes which are expert in making amazing handicrafts. The markets are lined with shops offering a variety of handicrafts such as cane mats, cane baskets, carpets, pineapple fiber articles, silk fabric, tribal jewellery and bamboo and cane objects. Cuisine The people of Meghalaya are more tilted towards meat, especially pork. It is an ingredient of most of their dishes. Don't forget to try out Jadoh, a delicious dish made of meat and rice. Also try Kyat which is a local brew of the state. “Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far they can go.” TENTATIVE - TOUR ITINERARY: DAY 01: DRIVE TO CHERRAPUNJEE, SIGHTSEEING IN CHERRAPUNJEE. Tour de India HOLIDAYS Arrive Guwahati Airport; Meet Our Representative - We will drive to Cherrapunjee. -

A Handbook on the Gram Sevak Circle-Wise Village List of All the 39 Development Blocks of Meghalaya

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA A HANDBOOK ON THE GRAM SEVAK CIRCLE-WISE VILLAGE LIST OF ALL THE 39 DEVELOPMENT BLOCKS OF MEGHALAYA (AS PER 2011 CENSUS) Directorate of Economics & Statistics Meghalaya, Shillong PREFACE The Handbook on the Gram Sevak circle-wise list of villages of Meghalaya - 2016 has been compiled based on the report submitted by the District Statistical Officers which are furnished by the Block Development Officers falling under their respective Districts. The hamlets/localities which are not notified as census villages as per census 2011 have been excluded from the Gram Sevak circles to bring into conformity with the village list of the population census 2011. During the population census 2011, the censuses on these hamlets/localities have been conducted as a hamlet/locality of the main/nearby notified census villages. I hope this Handbook will serve as a valuable source of information and ready reckoner to the Department concerned, economic planners, research scholars, students etc. about the villages falling within the Gram Sevak circles of each Development Block of all the Districts. Comments and suggestion from the users of this Handbook for improvement of its quality and usefulness will be highly appreciated. I would like to thank Shri Bruston Momin, R.O. who has compiled this Handbook. D. L. Wankhar, IES Director Page Index Name of the District Sl. No Name of the Dev. Block Page No. 1 Laskein 1-1 West Jaintia Hills 2 Thadlaskein 2-3 3 Amlarem 4-4 4 Khliehriat 5-5 East Jaintia Hills 5 Saipung 6-6 6 Pynursla 7-8 7 Shella Bholaganj 9-10 8 Mawsynram 11-12 9 Mawrynkneng 13 - 13 East Khasi Hills 10 Mawphlang 14 - 15 11 Mawkynrew 16 - 16 12 L. -

Through Mountains and Clouds

! " # $ DESTINATIONS " EXPERIENCES " PLAN YOUR TRIP ABOUT " ! % $ ITINERARIES THROUGH MOUNTAINS AND CLOUDS ! " # Recommended Length Destinations Covered Drive Start Time 5 Days Shillong, Sohra, Nongriat, Pynursla, 07:30 AM Shnongpdeng, Mawphlang A road trip across Meghalaya is exhilarating, not to mention scenic and full of adventure. Be it on a bike or a car, the journey is enthralling. Of the many routes you can take to explore the state, the one leading from its capital Shillong to one of the wettest places on Earth, Cherrapunjee (Cherrapunji or Sohra, as the locals like to call it), stands out owing to the stunning sights and majestic waterfalls on the way. Add the Pynursla region to your itinerary and you have yourself a guarantee of wondrous sights and experiences. Through Mountains and Clouds DAY 1 : SHILLONG # Start Explore locations in and around the city Spot 1 # WARD’S LAKE 1 Hour Start with Ward’s Lake, a horseshoe-shaped artificial pool, lying near Raj Bhavan and the accountant general’s office. The lake provides shelter to grass carps and gaggles of geese, and you can feed them standing on the bridge that passes over the lake. You can also take a stroll amidst flowerbeds and fairy-lights, and enjoy the greenery in the surrounding. The lake is supplemented by a cafeteria and has boating options for tourists. Spend at least one hour to soak in the attractions and serene scenes here. CATHEDRAL MARY HELP OF CHRISTIANS # Spot 2 30 Minutes Make your next stop at the old, imposing church building. It stands as an architectural highlight with its towering arches and stained glass. -

Botanical Study Tour of North East India November 2017

Botanical Study Tour of North East India November 2017 The “Double Decker” Living Bridge, Meghalaya Richard Holman 1 CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Participants 3 Aims and objectives 4 Itinerary 5 Journal of the Expedition 6 to 31 Conclusions 33 Learnings and Plans for the future 34 Final budget breakdown 36 Acknowledgements 37 Bibliography 37 2 INTRODUCTION This report details the highlights and main findings of a study trip to North East India which was made in November 2017. The trip involved travelling through Meghalaya, Assam, Nagaland and Manipur, mainly by road with excursions on foot to explore the local flora. I work at a National Trust garden in Cornwall (Trelissick near Truro, on the Fal Estuary). Here we are fortunate enough to be able to grow many species of plants which originate in the Sino-Himalayan region, the flora of which extends right down into the parts of North East India which we visited on this expedition. My previous Head Gardener at Trelissick (Tom Clarke, currently Head Gardener at Exbury) has been on two previous expeditions to Arunachal Pradesh in NE India, to study the flora and in particular the rhododendrons found there. Tom’s experiences and photographs from these trips really fired my imagination, and we had discussed the possibility of me joining him on his next trip, since we share a strong interest in the flora of India and the Sino-Himalayan region. Tom Clarke had intended to join John Anderson on this study trip to North East India. In the event, Tom decided that he would not be able to make this trip due to other commitments, but he proposed that I take his place instead. -

Sustainable Design and Architecture Living Root Tree Bridges by Paul Anthony IDC, IIT Bombay

D’source 1 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Sustainable Design and Architecture Living Root Tree Bridges by Paul Anthony IDC, IIT Bombay Source: http://www.dsource.in/resource/sustainable-de- sign-and-architecture 1. Introduction 2. Location 3. Terrain 4. Fauna 5. The Tree 6. War-Khasis 7. Architecture 8. Contemporary Bridges 9. Conclusion 10. Links/References 11. Contact Details D’source 2 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Introduction Sustainable Design and Shillong city lies in the centre of the plateau structure in the Northeastern state of Meghalaya in India. The city is Architecture surrounded by a set of three hills, which as per the indigenous Khasi people is known as, LumSohpetbneng (Navel Living Root Tree Bridges of the Earth), Lum Diengiei (Mount of the merciful tree) and LumShillong (Mount of Shillong, a deity). The region by is known to possess many scenic elements like fast moving rivers and streams, naturally formed limestone caves, Paul Anthony natural and artificial lakes. One of the major tourist attractions however, belong to villages in Sohra (Cherrapun- IDC, IIT Bombay ji) and Mawlynnong viz. the living root-tree bridges. This is a documentation of the bridges in Nongriat which is a small village located in Shella Bholaganj of East Khasi Hills district, Meghalaya with total 31* families residing. *Census 2011.co.in, (2015). Nongriat Village Population - Shella Bholaganj - East Khasi Hills, Meghalaya. Ref.: http://www.census2011.co.in/data/village/278802-nongriat-meghalaya.html Source: http://www.dsource.in/resource/sustainable-de- sign-and-architecture/introduction 1.