Arxiv:1307.1188V1 [Math.DS]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problem Books in Mathematics

Problem Books in Mathematics Edited by K.A. Bencsath P.R. Halmos Springer-Science+Business Media, LLC Problem Books in Mathematics Series Editors: K.A. Bencsath and P.R. Halmos Pell's Equation by Edward J. Barbeau Polynomials by Edward J. Barbeau Problems in Geometry by Marcel Berger, Pierre Pansu, Jean-Pic Berry, and Xavier Saint-Raymond Problem Book for First Year Calculus by George W Bluman Exercises in Probability by T. Cacoullos Probability Through Problems by Marek Capinski and Tomasz Zastawniak An Introduction to Hilbert Space and Quantum Logic by David W Cohen Unsolved Problems in Geometry by Ballard T. Croft, Kenneth J. Falconer, and Richard K Guy Berkeley Problems in Mathematics, (Third Edition) by Paulo Ney de Souza and Jorge-Nuno Silva Problem-Solving Strategies by Arthur Engel Problems in Analysis by Bernard R. Gelbaum Problems in Real and Complex Analysis by Bernard R. Gelbaum Theorems and Counterexamples in Mathematics by Bernard R. Gelbaum and John MH. Olmsted Exercises in Integration by Claude George (continued after index) Richard K. Guy Unsolved Problems in Number Theory Third Edition With 18 Figures , Springer Richard K. Guy Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, Alberta Canada T2N IN4 [email protected] Series Editors: Katalin A. Bencsath Paul R. Halmos Mathematics Department of Mathematics School of Science Santa Clara University Manhattan College Santa Clara, CA 95053 Riverdale, NY 10471 USA USA [email protected] [email protected] Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): OOA07, 11-01, 11-02 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guy, Richard K. -

Problem Books in Mathematics

Problem Books in Mathematics Edited by P. R. Halmos Problem Books in Mathematics Series Editor: P.R. Halmos Polynomials by Edward I. Barbeau Problems in Geometry by Marcel Berger. Pierre Pansu. lean-Pic Berry. and Xavier Saint-Raymond Problem Book for First Year Calculus by George W. Bluman Exercises in Probabillty by T. Cacoullos An Introduction to HUbet Space and Quantum Logic by David W. Cohen Unsolved Problems in Geometry by Hallard T. Crofi. Kenneth I. Falconer. and Richard K. Guy Problems in Analysis by Bernard R. Gelbaum Problems in Real and Complex Analysis by Bernard R. Gelbaum Theorems and Counterexamples in Mathematics by Bernard R. Gelbaum and lohn M.H. Olmsted Exercises in Integration by Claude George Algebraic Logic by S.G. Gindikin Unsolved Problems in Number Theory (2nd. ed) by Richard K. Guy An Outline of Set Theory by lames M. Henle Demography Through Problems by Nathan Keyjitz and lohn A. Beekman (continued after index) Unsolved Problems in Intuitive Mathematics Volume I Richard K. Guy Unsolved Problems in Number Theory Second Edition With 18 figures Springer Science+Business Media, LLC Richard K. Guy Department of Mathematics and Statistics The University of Calgary Calgary, Alberta Canada, T2N1N4 AMS Classification (1991): 11-01 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guy, Richard K. Unsolved problems in number theory / Richard K. Guy. p. cm. ~ (Problem books in mathematics) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4899-3587-8 1. Number theory. I. Title. II. Series. QA241.G87 1994 512".7—dc20 94-3818 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 1994 Originally published by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. -

Predicate Logic

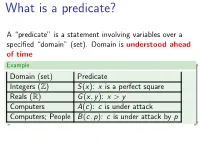

What is a predicate? A \predicate" is a statement involving variables over a specified \domain" (set). Domain is understood ahead of time Example Domain (set) Predicate Integers (Z) S(x): x is a perfect square Reals (R) G(x; y): x > y Computers A(c): c is under attack Computers; People B(c; p): c is under attack by p Quantification Existential quantifier: 9x (exists x) Universal quantifier: 8x (for all x) Domain D (9x)[P(x)]: Exists x in D such that P(x) is true. (8x)[P(x)]: For all x in D, P(x) is true. If Domain not understood OR if want to use D0 ⊆ D: (9x 2 D0)[P(x)] (8x 2 D0)[P(x)] Examples From Mathematics Domain is the natural numbers. Want to express everything just using +; −; ×; ÷; =; ≤; ≥ Want predicates for 1 x is a odd. 2 x is a composite. 3 x is a prime. 4 x is the sum of three odd numbers. Want to express Vinogradov's Theorem: For every sufficiently large odd number is the sum of three primes. Do All of this in class Examples From Mathematics Domain is the natural numbers. Want to express everything just using +; −; ×; ÷; =; ≤; ≥ Want predicates for 1 x is a square. 2 When you divide x by 4 you get a remainder of 1. Want to express Theorem: Every prime that when you divide by 4 you get a remainder of 1 can be written as the sum of two squares. Establishing Truth and Falsity To show 9 statement is true: Find an example in the domain where it is true. -

![Arxiv:2009.01114V4 [Math.NT] 20 Oct 2020 on the Erd˝Os-Sloane And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6949/arxiv-2009-01114v4-math-nt-20-oct-2020-on-the-erd-os-sloane-and-8416949.webp)

Arxiv:2009.01114V4 [Math.NT] 20 Oct 2020 on the Erd˝Os-Sloane And

On the Erd˝os-Sloane and Shifted Sloane Persistence Problems Gabriel Bonuccelli Lucas Colucci Edson de Faria Instituto de Matem´atica e Estat´ıstica Universidade de S˜ao Paulo S˜ao Paulo Brazil gabrielbhl,lcolucci,edson @ime.usp.br { } Abstract In this paper, we investigate two variations on the so-called persistence problem of Sloane: the shifted version, which was introduced by Wagstaff; and the nonzero version, proposed by Erd˝os. We explore connections between these problems and a recent conjecture of de Faria and Tresser regarding equidistribution of the digits of some integer sequences and a natural generalization of it. 1 Introduction In 1973, Sloane [9] proposed the following question: given a positive integer n, multiply all its digits together to get a new number, and keep repeating this operation until a single-digit arXiv:2009.01114v4 [math.NT] 20 Oct 2020 number is obtained. The number of operations needed is called the persistence of n. Is it true that there is an absolute constant C(b) (depending solely on the base b in which the numbers are written) such that the persistence of every positive integer is bounded by C(b)? Despite many computational searches, heuristic arguments and related conjectures in favor of a positive answer, no proof or disproof of this conjecture has been found so far. Many variants of Sloane’s problem have been considered as well. The famous book of Guy [5] mentions that Erd˝os introduced the version of the Sloane problem wherein only the This work has been supported by “Projeto Tem´atico Dinˆamica em Baixas Dimens˜oes” FAPESP Grant 2016/25053-8 1 nonzero digits of a number are multiplied in each iteration, which we call the Erd˝os-Sloane problem. -

The Eleven Set Contents

0_11 The Eleven Set Contents 1 1 1 1.1 Etymology ............................................... 1 1.2 As a number .............................................. 1 1.3 As a digit ............................................... 1 1.4 Mathematics .............................................. 1 1.4.1 Table of basic calculations .................................. 3 1.5 In technology ............................................. 3 1.6 In science ............................................... 3 1.6.1 In astronomy ......................................... 3 1.7 In philosophy ............................................. 3 1.8 In literature .............................................. 4 1.9 In comics ............................................... 4 1.10 In sports ................................................ 4 1.11 In other fields ............................................. 6 1.12 See also ................................................ 6 1.13 References ............................................... 6 1.14 External links ............................................. 6 2 2 (number) 7 2.1 In mathematics ............................................ 7 2.1.1 List of basic calculations ................................... 8 2.2 Evolution of the glyph ......................................... 8 2.3 In science ............................................... 8 2.3.1 Astronomy .......................................... 8 2.4 In technology ............................................. 9 2.5 In religion .............................................. -

Mathfest 2012

Abstracts of Papers Presented at MathFest 2012 Madison, Wisconsin August 2–4, 2012 Published and Distributed by The Mathematical Association of America Contents Invited Addresses 1 EarlRaymondHedrickLectureSeries . ...................... 1 Algebraic Geometry: Tropical, Convex, and Applied by Bernd Sturmfels..................... 1 Lecture 1: Tropical Mathematics Thursday, August 2, 10:30–11:20 AM,BallroomAB ........................... 1 Lecture 2: Convex Algebraic Geometry Friday, August 3, 9:30–10:20 AM,BallroomAB ............................. 1 Lecture 3: The Central Curve in Linear Programing Saturday, August 4, 9:30–10:20 AM,BallroomAB ............................ 1 MAA-AMSJointInvitedAddress . ................... 1 The Synergy of Pure and Applied Math, of the Abstract and the Concrete by David Mumford Thursday, August 2, 8:30–9:20 AM,BallroomAB............................. 1 MAAInvitedAddresses. ........ ........ ....... ........ .................. 1 Chaotic Stability, Stable Chaos by Amie Wilkinson Thursday, August 2, 9:30–10:20 AM,BallroomAB............................ 1 Random Interfaces and Limit Shapes by Richard Kenyon Saturday, August 4, 8:30–9:20 AM,BallroomAB............................. 2 Putting Topology to Work by Robert Ghrist Saturday, August 4, 10:30–11:20 AM,BallroomAB............................ 2 AWM-MAAEtta.Z.FalconerLecture . .................... 2 Because I Love Mathematics: The Role of Disciplinary Grounding in Mathematics Education by Karen King Friday, August 3, 8:30–9:20 AM,BallroomAB ............................. -

Scientia Magna

Vol. 2, No. 1, 2006 ISSN 1556-6706 SCIENTIA MAGNA Department of Mathematics Northwest University Xi’an, Shaanxi, P. R. China Vol. 2, No. 1, 2006 ISSN 1556-6706 SCIENTIA MAGNA Edited by Department of Mathematics Northwest University Xi’an, Shaanxi, P.R.China Scientia Magna is published annually in 100-200 pages per volume and 1,000 copies. It is also available in microfilm format and can be ordered (online too) from: Books on Demand ProQuest Information & Learning 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346, USA Tel.: 1-800-521-0600 (Customer Service) URL: http://wwwlib.umi.com/bod/ Scientia Magna is a referred journal: reviewed, indexed, cited by the following journals: "Zentralblatt Für Mathematik" (Germany), "Referativnyi Zhurnal" and "Matematika" (Academia Nauk, Russia), "Mathematical Reviews" (USA), "Computing Review" (USA), Institute for Scientific Information (PA, USA), "Library of Congress Subject Headings" (USA). Printed in the United States of America Price: US$ 69.95 Information for Authors Papers in electronic form are accepted. They can be e-mailed in Microsoft Word XP (or lower), WordPerfect 7.0 (or lower), LaTeX and PDF 6.0 or lower. The submitted manuscripts may be in the format of remarks, conjectures, solved/unsolved or open new proposed problems, notes, articles, miscellaneous, etc. They must be original work and camera ready [typewritten/computerized, format: 8.5 x 11 inches (21,6 x 28 cm)]. They are not returned, hence we advise the authors to keep a copy. The title of the paper should be writing with capital letters. The author's name has to apply in the middle of the line, near the title. -

Unsolved Problems in Number Theory

Richard K. Guy Unsolved Problems in Number Theory Third Edition With 18 Figures Springer Contents Preface to the Third Edition v Preface to the Second Edition vii Preface to the First Edition ix Glossary of Symbols xi Introduction 1 A. Prime Numbers 3 Al. Prime values of quadratic functions. 7 A2. Primes connected with factorials. 10 A3. Mersenne primes. Repunits. Fermat numbers. Primes of shape k • 2n + 1. 13 A4. The prime number race. 22 A5. Arithmetic progressions of primes. 25 A6. Consecutive primes in A.P. 28 A7. Cunningham chains. 30 A8. Gaps between primes. Twin primes. 31 A9. Patterns of primes. 40 A10. Gilbreath's conjecture. 1^2 All. Increasing and decreasing gaps. 43 A12. Pseudoprimes. Euler pseudoprimes. Strong pseudoprimes. 44 A13. Carmichael numbers. 50 A14. "Good" primes and the prime number graph. 54 A15. Congruent products of consecutive numbers. 54 A16. Gaussian and Eisenstein-Jacobi primes. 55 A17. Formulas for primes. 58 A18. The Erdos-Selfridge classification of primes. 66 A19. Values of n making n — 2k prime. Odd numbers not of the form ±pa ± 2b. 67 A20. Symmetric and asymmetric primes. 69 B. Divisibility 71 Bl. Perfect numbers. 71: B2. Almost perfect, quasi-perfect, pseudoperfect, harmonic, weird, multiperfect and hyperperfect numbers. 74 B3. Unitary perfect numbers. 84 B4. Amicable numbers. 86 B5. Quasi-amicable or betrothed numbers. 91 B6. Aliquot sequences. 92 B7. Aliquot cycles. Sociable numbers. 95 B8. Unitary aliquot sequences. 97 B9. Superperfect numbers. 99 BIO. Untouchable numbers. 100 xv xvi Contents Bll. Solutions of ma(m) = ncr(n). 101 B12. Analogs with d(n), CTfc(n). -

On Some Properties of Digital Roots

Advances in Pure Mathematics, 2014, 4, 295-301 Published Online June 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/apm http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/apm.2014.46039 On Some Properties of Digital Roots Ilhan M. Izmirli Department of Statistics, George Mason University, Fairfax, USA Email: [email protected] Received 23 March 2014; revised 24 April 2014; accepted 9 May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Digital roots of numbers have several interesting properties, most of which are well-known. In this paper, our goal is to prove some lesser known results concerning the digital roots of powers of numbers in an arithmetic progression. We will also state some theorems concerning the digital roots of Fermat numbers and star numbers. We will conclude our paper by an interesting applica- tion. Keywords Digital Roots, Additive Persistence, Perfect Numbers, Mersenne Primes, Fermat Numbers, Star Numbers 1. Introduction The part of mathematics that deals with the properties of specific types of numbers and their uses in puzzles and recreational mathematics has always fascinated scientists and mathematicians (O’Beirne 1961 [1], Gardner 1987 [2]). In this short paper, we will talk about digital roots—a well-established and useful part of recreational mathe- matics which materializes in as diverse applications as computer programming (Trott 2004) [3] and numerology (Ghannam 2012 [4]). As will see, digital roots are equivalent to modulo 9 arithmetic (Property 1.6) and hence can be thought of as a special case of modular arithmetic of Gauss (Dudley, 1978) [5].