The Legacy of Hilda Lazarus Ruth Compton Brouwer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edinburgh 1910: Friendship and the Boundaries of Christendom

Vol. 30, No. 4 October 2006 Edinburgh 1910: Friendship and the Boundaries of Christendom everal of the articles in this issue relate directly to the take some time before U.S. missionaries began to reach similar Sextraordinary World Missionary Conference convened conclusions about their own nation. But within the fifty years in Edinburgh from June 14 to 23, 1910. At that time, Europe’s following the Second World War, profound uncertainty arose global hegemony was unrivaled, and old Christendom’s self- concerning the moral legitimacy of America’s global economic assurance had reached its peak. That the nations whose pro- Continued next page fessed religion was Christianity should have come to dominate the world seemed not at all surprising, since Western civiliza- tion’s inner élan was thought to be Christianity itself. On Page 171 Defining the Boundaries of Christendom: The Two Worlds of the World Missionary Conference, 1910 Brian Stanley 177 The Centenary of Edinburgh 1910: Its Possibilities Kenneth R. Ross 180 World Christianity as a Women’s Movement Dana L. Robert 182 Noteworthy 189 The Role of Women in the Formation of the World Student Christian Federation Johanna M. Selles 192 Sherwood Eddy Pays a Visit to Adolf von Harnack Before Returning to the United States, December 1918 Mark A. Noll The Great War of 1914–18 soon plunged the “Christian” nations into one of the bloodiest and most meaningless parox- 196 The World is Our Parish: Remembering the ysms of state-sanctioned murder in humankind’s history of 1919 Protestant Missionary Fair pathological addiction to violence and genocide. -

1St Interim Dividend 2012-2013

List of shareholders unpaid/unclaimed Dividend Amount - Interim Dividend 2012-2013 Date of Declaration of Dividend : 20th July ,2012 NAME ADDRESS FOLIO/DP_CL ID AMOUNT PROPOSED DATE OF (RS) TRANSFER TO IEPF ( DD-MON-YYYY) ACHAR MAYA MADHAV NO 9 BRINDAVAN 353 B 10 VALLABH BHAG ESTATE GHATKOPAR EAST BOMBAY 400077 0000030 256.00 19-AUG-2019 ANNAMALAL RABINDRAN 24 SOUTH CHITRAI STREET C O POST BOX 127 MADURAI 1 625001 0000041 256.00 19-AUG-2019 AHMED ZAMIR H NO 11 1 304 2 NEW AGHAPURA HYDERABAD 1 A P 500001 0000059 420.00 19-AUG-2019 ROSHAN DADIBA ARSIWALLA C O MISS SHIRIN OF CHOKSI F 2 DALAL ESTATE F BLOCK GROUND FLOOR DR D BHADKAMKAR ROAD MUMBAI 400008 0000158 16.00 19-AUG-2019 VIVEK ARORA 127 ANOOP NAGAR INDORE M P 452008 0000435 410.00 19-AUG-2019 T J ASHOK M 51 ANNA NAGAR EAST MADRAS TAMIL NADU 600102 0000441 84.00 19-AUG-2019 ARUN BABAN AMBEKAR CROMPTON GREAVES LTD TOOL ROOM A 3 MIDC AMBAD NASIK 422010 0000445 40.00 19-AUG-2019 NARENDRA ASHAR 603 NIRMALA APPARTMENTS J P ROAD ANDHERI WEST BOMBAY 400078 0000503 420.00 19-AUG-2019 ALOO BURJOR JOSHI MAYO HOUSE 9 COOPERAGE ROAD BOMBAY 400039 0000582 476.00 19-AUG-2019 ALKA TUKARAM CHAVAN 51 5 NEW MUKUNDNAGAR AHMEDNAGAR 414001 0000709 40.00 19-AUG-2019 AYRES JOAQUIM SALVADORDCRUZ 10 DANRAY BLDG 1ST FLOOR DOMINIC COLONY 2ND TANK RD ORLEM MALAD W BOMBAY 400064 0000799 400.0019-AUG-2019 ANTHONY FERNANDES C O CROMPTON GREAVES LTD MISTRY CHAMBERS KHANPUR AHMEDABAD 380001 0000826 760.00 19-AUG-2019 BHARATI BHASKAR GAMBHIRRAI SINGH NIWAS B 3 41 JANTA COLONY JOGESHWARI EAST MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 400060 -

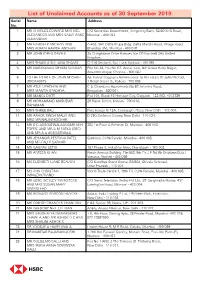

List of Unclaimed Accounts As of 30 September 2019. Serial Name Address No

List of Unclaimed Accounts as of 30 September 2019. Serial Name Address No. 1 MR CHARLES EDWARD MICHAEL C/O Securtiies Department, Hongkong Bank, 52/60 M G Road, ALEXANDER AND MRS SALLY ANNE Mumbai - 400 023 ALEXANDER 2 MR HARISH P ANCHAN AND A-402, Shri Datta Krupa Bldg, Datta Mandir Road, Village Road, MRS ROHINI HARISH ANCHAN Bhandup (W), Mumbai - 400 078. 3 MR JOHN IDRES DAVIES 25 Claughbane Drive Ramsey Isle Of Man Im8 2Ay United Kingdom. 4 MRS SHAKILA SULTANA SHAMS Cl-176 Sector-II, Salt Lake, Kolkata - 700 091. 5 MR NARAYANAN SHYAM SUNDAR Plot No 34, Flat No G2, Annai Illam, 6th Street Balaji Nagar, Alwarthirunagar, Chennai - 600 087. 6 TO THE ESTATE OF JOHN MICHAEL Ajit Kumar Dasgupta Administrator To The Estate Of John Michael, (DECEASED) 1 British Indian St, Kolkata - 700 069. 7 MR ATUL UPADHYA AND C-5, Chandana Apartments No 82, Infantry Road, MRS MAMTA UPADHYA Bengaluru - 560 001. 8 MR MANOJ DUTT Flat 101, Block 45 Heritage City, Gurgaon - 122 002. 4013739 9 MR MOHAMMAD MASUDAR 28 Ripon Street, Kolkata - 700 016. RAHAMAN 10 MRS SHREE BALI Punj House M 13A, Connaught Place, New Delhi - 110 001. 11 MR ASHOK SINGH MALIK AND D-250, Defence Colony, New Delhi - 110 024. MRS MRINALINI KOCHAR 12 MR S D AGBOATWALAANDMR M H 282 1st Floor A Rehman St, Mumbai - 400 003. TOFFIC AND MR A M PATKA (DEC) AND MR A A AGBOATWALA 13 MR JEHANGIR PESTONJI PATEL Gulestan, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai - 400 005. AND MR FALI P SARKARI 14 MR GAURAV SETHI 157 Phase II, Industrial Area, Chandigarh - 160 002. -

To Download As

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/18-20 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/18-20 Publication: 1st & 16th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) INSIDE Short ‘N’ Snappy A house of Music Water sustainable Chennai Memoirs of P. Sabanayagam Women Doctors of Chennai www.madrasmusings.com WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI Vol. XXIX No. 18 January 1-15, 2020 Creating Urban Transport Chaos t was exactly a year ago that was yet another example, and involved in the running of the Ithe Chennai Unified Met- in TN there are many, of how transport systems. It was also to ropolitan Transport Authority the public suffers at the whims periodically revise and upgrade (CUMTA) was launched with of those in power. The CUMTA its plans. Headed by the Trans- much fanfare. The media had was an excellent scheme and port Minister, it was to have the at that time hailed it, claiming its non-implementation has Chief Urban Planner (Trans- that it was the solution to all the helped nobody. In January 2019 port) of the CMDA as its Mem- ills that city’s public transport it was relaunched with much ber-Secretary. Others on board As our leads concern public amenities, our OLD features private systems faced – each of them were the Chief Secretary and buses waiting outside Central Station in the 1920s. Our NEW is striking out in different direc- the Vice-Chairman, CMDA the famed ‘green’ bus launched recently. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2012 [Price: Rs. 28.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 41] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2012 Aippasi 1, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2043 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Change of Names .. 2591-2661 Notices .. 2661-2662 .. 2240-2242 .. 1764 1541-1617NOTICE Notice .. 1617 NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 38565. I, C. Vasanthi, daughter of Thiru Aruliah, born on 38568. I, K.P.S. Alshiba, daughter of Thiru K.P. Saleem 12th May 1951 (native district: Theni), residing at Raja, born on 13th November 1992 (native district: No. W-4/103, Church Street, Anaimalayanpatti, Ramanathapuram), residing at No. 4/190, Raja Street, Uthamapalayam Taluk, Theni-625 526, shall henceforth be Thasildhar Nagar, Madurai-625 020, shall henceforth be known as A. VASANTHASELVI. known as K.P.S ALSIFA BANU. C. VASANTHI. K.P.S. ALSHIBA. Theni, 8th October 2012. Madurai, 8th October 2012. 38566. I, M. Hemanth Kumar, son of Thiru S. Mithalal Jain, 38569. My son, K.P.S. Shahul Hameed, born on 13th August born on 9th July 1989 (native district: Jalore-Rajasthan), 1997 (native district: Ramanathapuram), residing at No. 4/190, residing at No. 16, Jadamuni Koil Street, East Lane, Raja Street, Thasildhar Nagar, Madurai-625 020, shall Madurai-625 001, shall henceforth be known henceforth be known as K.P.S. -

In Pensioners Patrika

NAMES OF LIFE MEMEBRS THAT COULD NOT BE PUBLSIHED IN PENSIONERS PATRIKA . We published 44068 names in Patrika . 8421 Names in waiing list are given below. Circle Branch Life member AP Ananthapuram A. B. Gopal AP Ananthapuram A. Kambagiri AP Ananthapuram A. Ramana Reddy AP Ananthapuram A. Viswa Nath AP Ananthapuram Abdul Mujeeb AP Ananthapuram B. Krishna Murthy AP Ananthapuram B. Prabhakar AP Ananthapuram B. Rajaram AP Ananthapuram B. Venkata Narayana AP Ananthapuram C. Krishna Murthy AP Ananthapuram C. Narayana AP Ananthapuram C. Prema Rao AP Ananthapuram C. V. Narayana Reddy AP Ananthapuram D M B Gowd AP Ananthapuram D. Krishtappa AP Ananthapuram D. Narayana AP Ananthapuram D. Ramamurthy AP Ananthapuram Devendramma AP Ananthapuram E. Chidananda Murthy AP Ananthapuram E. Narothama Reddy AP Ananthapuram G. A. Chandra Sekhar AP Ananthapuram G. Adinarayna AP Ananthapuram G. Chaya Devi AP Ananthapuram G. Ramamohan AP Ananthapuram G. Subbarayudu AP Ananthapuram G. Subramanyam AP Ananthapuram G. Suresh Babu AP Ananthapuram G. Vasantha Reddy AP Ananthapuram J. Chandra Sekhar AP Ananthapuram J. S. Ramaiah AP Ananthapuram K. Adinarayana AP Ananthapuram K. Eswaraiah AP Ananthapuram K. Eswaraiah AP Ananthapuram K. Ghouse Mohinuddin AP Ananthapuram K. Kamakshamma, AP Ananthapuram K. Mastan Vali AP Ananthapuram K. Narayana Rao AP Ananthapuram K. Raghavendra AP Ananthapuram K. Raghu Rami Reddy AP Ananthapuram K. Ravindra Nath AP Ananthapuram K. Sivudu AP Ananthapuram K. Venkata Chalapathi AP Ananthapuram M. Mallikarjuna Reddy AP Ananthapuram M. Nagabhushana M AP Ananthapuram M. Nagaraju AP Ananthapuram M. Nagi Reddy AP Ananthapuram M. Nirupama Devi AP Ananthapuram M. Rajasekhara Reddy AP Ananthapuram M. Ravindra Reddy AP Ananthapuram M. -

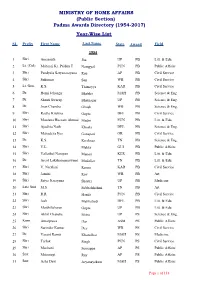

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt. -

Circle Branch Life Member 1 AP Anantapur a Subbarayulu 2 AP Anantapur A

WE HAVE 58192 LIFE MEMBERS AS ON 28-2-2021 We have published 44068 names in Pensioners Partrika till March 2020 14124 names in waiting list, that could not be published, are given below. Srl. Circle Branch Life Member 1 AP Anantapur A Subbarayulu 2 AP Anantapur A. B. Gopal 3 AP Anantapur A. Kambagiri 4 AP Anantapur A. Ramana Reddy 5 AP Anantapur A. Viswa Nath 6 AP Anantapur Abdul Mujeeb 7 AP Anantapur B G Ramanjaneyulu 8 AP Anantapur B Prabhakara 9 AP Anantapur B Venkatarao 10 AP Anantapur B. Krishna Murthy 11 AP Anantapur B. Prabhakar 12 AP Anantapur B. Rajaram 13 AP Anantapur B. Venkata Narayana 14 AP Anantapur C Narayana 15 AP Anantapur C Obulesu 16 AP Anantapur C Tiruppalaiah 17 AP Anantapur C V Nagamani 18 AP Anantapur C. Krishna Murthy 19 AP Anantapur C. Narayana 20 AP Anantapur C. Prema Rao 21 AP Anantapur C. V. Narayana Reddy 22 AP Anantapur D M B Gowd 23 AP Anantapur D. Krishtappa 24 AP Anantapur D. Narayana 25 AP Anantapur D. Ramamurthy 26 AP Anantapur Devendramma 27 AP Anantapur E. Chidananda Murthy 28 AP Anantapur E. Narothama Reddy 29 AP Anantapur G Sreenivasulu 30 AP Anantapur G Tirupathaiah 31 AP Anantapur G. A. Chandra Sekhar 32 AP Anantapur G. Adinarayna 33 AP Anantapur G. Chaya Devi 34 AP Anantapur G. Ramamohan 35 AP Anantapur G. Subbarayudu 36 AP Anantapur G. Subramanyam 37 AP Anantapur G. Suresh Babu 38 AP Anantapur G. Vasantha Reddy 39 AP Anantapur J Krishna Kambaiah 40 AP Anantapur J. Chandra Sekhar 41 AP Anantapur J.