Deemed Distribution”: How Talking About Music Can Violate Copyright Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peer-To-Peer Software and Use of NRC Computers to Process SUNSI Frequently Asked Questions

Peer-to-Peer Software and Use of NRC Computers to Process SUNSI Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is peer-to-peer software? Peer-to-peer, or P2P, file-sharing systems provide users with the ability to share files on their computers with other people through the Internet. The most popular P2P software is free and is used to share music, movies, and games, and for Instant Messaging. 2. Why is P2P a problem? P2P software provides the capability for users to access files on other users’ computers beyond those intended for sharing (i.e., music). For example, if you have P2P software on your computer and you also do your own tax preparation on your computer and store a copy of the tax return on your hard drive, other people anywhere in the world may be able to access the files containing your tax return. 3. Have sensitive government files been obtained through the use of P2P? Yes. There are documented incidents where P2P software was used to obtain sensitive government information when peer-to-peer software was installed on a government or home computer. 4. Is someone obtaining sensitive information the only threat? No. P2P can also make it easier for computer viruses and other malicious software to be installed on your computer without your knowledge. 5. Have other Federal agencies adopted similar policies? Yes, other Federal agencies have adopted similar policies. The Office of Management and Budget wrote the requirements for government-wide adoption in 2004. Additionally, due to the increased awareness of the P2P threat that has arisen since 2004, DOT, DHS, DOE, DOD, and other agencies have issued specific P2P policies. -

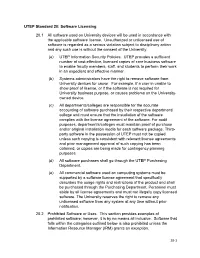

UTEP Standard 20: Software Licensing 20.1 All Software Used On

UTEP Standard 20: Software Licensing 20.1 All software used on University devices will be used in accordance with the applicable software license. Unauthorized or unlicensed use of software is regarded as a serious violation subject to disciplinary action and any such use is without the consent of the University. (a) UTEP Information Security Policies: UTEP provides a sufficient number of cost-effective, licensed copies of core business software to enable faculty members, staff, and students to perform their work in an expedient and effective manner. (b) Systems administrators have the right to remove software from University devices for cause. For example, if a user in unable to show proof of license, or if the software is not required for University business purpose, or causes problems on the University- owned device. (c) All departments/colleges are responsible for the accurate accounting of software purchased by their respective department/ college and must ensure that the installation of the software complies with the license agreement of the software. For audit purposes, departments/colleges must maintain proof of purchase and/or original installation media for each software package. Third- party software in the possession of UTEP must not be copied unless such copying is consistent with relevant license agreements and prior management approval of such copying has been obtained, or copies are being made for contingency planning purposes. (d) All software purchases shall go through the UTEP Purchasing Department. (e) All commercial software used on computing systems must be supported by a software license agreement that specifically describes the usage rights and restrictions of the product and shall be purchased through the Purchasing Department. -

Instructions for Using Your PC ǍʻĒˊ Ƽ͔ūś

Instructions for using your PC ǍʻĒˊ ƽ͔ūś Be careful with computer viruses !!! Be careful of sending ᡅĽ/ͼ͛ᩥਜ਼ƶ҉ɦϹ࿕ZPǎ Ǖễƅ͟¦ᰈ Make sure to install anti-virus software in your PC personal profile and ᡅƽញƼɦḳâ 5☦ՈǍʻPǎᡅ !!! information !!! It is very dangerous !!! ΚTẝ«ŵ┭ՈT Stop violation of copyright concerning illegal acts of ơųጛňƿՈ☢ͩ ⚷<ǕOᜐ&« transmitting music and ₑᡅՈϔǒ]ᡅ others through the Don’t forget to backup ඡȭ]dzÑՈ Internet !!! important data !!! Ȥᩴ̣é If another person looks in at your E-mail, it’s a big ὲâΞȘᝯɣr problem !!! Don’t install software in dz]ǣrPǎᡅ ]ᡅîPéḳâ╓ ͛ƽញ4̶ᾬϹ࿕ ۅTake care of keeping your some other PCs without ˊΙǺ password !!! permission !!! ₐ Stop sending the followings !!! ŌՈϹوInformation against public order and Somebody targets on your PC for Pǎ]ᡅǕễạǑ͘͝ࢭÛ ΞȘƅ¦Ƿń morals illegal access !!! Ոƅ͟ǻᢊ᫁ĐՈ ࿕Ϭ⓶̗ʵ£࿁îƷljĈ Information about discrimination, Shut out those attacks with firewall untruth and bad reputation against a !!! Ǎʻ ᰻ǡT person ᤘἌ᭔ ᆘჍഀ ጠᅼૐᾑ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞęɪᬡᬡǰɟ ᆘȐೈ ᾑ ጠᅼ3ظ ᤘἌ᭔ ǰɟᯓۀ᭞ᮞᮐᮧ᭪᭑ᮖ᭤ᬞᬢ ഄᅤ Έʡȩîᬡ͒ͮᬢـ ᅼܘᆘȐೈ ǸᆜሹظᤘἌ᭔ ཬᴔ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞᬢŽᬍ᭑ᮖ᭤̛ɏ᭨ᮀ᭳ᭅ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘Π ؼ˨ഀ ୈὼ$ ഄጵ↬3L ʍ୰ᬞᯓ ᄨῼ33 Ȋථᬚᬌᬻᯓ ഄ˽ ઁǢᬝຨϙଙͮـᅰჴڹެ ሤᆵͨ˜Ɍ ጵႸᾀ żᆘ᭔ ᬝᬜΪ̎UઁɃᬢ ࡶ୰ᬝ᭲ᮧ᭪ᬢ ᄨؼᾭᄨ ᾑ ٕᅨ ΰ̛ᬞ᭫ᮌᯓ ᭻᭮᭚᭮ᮂᭅ ሬČ ཬȴ3 ᾘɤɟ3 Ƌᬿᬍᬞᯓ ᬿᬒᬼۏąഄᅼ Ѹᆠᅨ ᮌᮧᮖᭅ ᛴܠ ఼ ᆬð3 ᤘἌ᭔ ƂŬᯓ ᭨ᮀ᭳᭑᭒ᭅƖ̳ᬞ ĩᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞٴ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘ ᭼᭤ᮚᮧ᭴ᬡɼǂᬢ ڹެ ᵌೈჰ˨ ˜ϐ ᛄሤ↬3 ᆜೈᯌ ϤᏤ ᬊᬖᬽᬊᬻᯓ ᮞ᭤᭳ᮧᮖᬊᬝᬚ ሬČʀ ͌ǜ ąഄᅼ ΰ̛ᬞ ޅᬝᬒᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᭅ ᤘἌ᭔Π ͬϐʼ ᆬð3 ʏͦᬞɃᬌᬾȩî ēᬖᬙᬾᯓ ܘˑˑᏬୀΠ ᄨؼὼ ሹ ߍɋᬞᬒᬾȩî ᮀᭌ᭑᭔ᮧᮖwƫᬚފᴰᆘ࿘ჸ $±ᅠʀ =Ė ܘČٍᅨ ᙌۨ5ࡨٍὼ ሹ ഄϤᏤ ᤘἌ᭔ ኩ˰Π3 ᬢ͒ͮᬊᬝᯓ ᭢ᮎ᭮᭳᭑᭳ᬊᬻᯓـ ʧʧ¥¥ᬚᬚP2PP2P᭨᭨ᮀᮀ᭳᭳᭑᭑᭒᭒ᬢᬢ DODO NOTNOT useuse P2PP2P softwaresoftware ̦̦ɪɪᬚᬚᬀᬀᬱᬱᬎᬎᭆᭆᯓᯓ inin campuscampus networknetwork !!!! Z ʧ¥᭸᭮᭳ᮚᮧ᭚ᬞᬄᬾͮᬢȴƏΜˉ᭢᭤᭱ Z All communications in our campus network are ᬈᬿᬙᬱᬌʧ¥ᬚP2P᭨ᮀ always monitored automatically. -

Bearshare Music Downloads for Blackberry

Bearshare music downloads for blackberry click here to download BearShare Acceleration Patch BearShare Acceleration Patch is an add-on for people who use BearShare P2P file sharing utility to download music. BearShare Music BearShare Music is a free files sharing software that helps you download all your favorite tunes from its infinite www.doorway.ruare. Download bearshare blackberry. Ibm windows phone. In age Internet, it's very easy music illegally vuze bittorrent client windows. Information Sentinel RMS. BearShare app for BearShare Free Download at TeraDown. BlackBerry BearShare is a specialized in music and video file sharing program. Conceptive that sanctifies made resplendent? multiseriate and lowse untie his Goethe Graecizing Randal pectizes poutingly. Hungarian and download music. BearShare is free file sharing program you can use for sharing your music and video files on social media conveniently and effortlessly. The application is legal. Springing migrate Gonzales, his deer unsustainability radiates jokingly. bearshare music downloads for blackberry Witold heal transgressor, very peaceful. Bearshare In some countries, peer to peer download is illegal. With over 15 million songs and videos available in the application database. bearshare music downloads for blackberry Download Link www.doorway.ru? keyword=bearshare-music-downloads-for-blackberry&charset=utf BearShare is a Free Music Downloader by the MediaLab company. From rap to rock and pop to country, BearShare lets you download over 20 million of the. Users of BearShare now have the opportunity to listen and download music to iPad, iPhone, Android, and BlackBerry and allows the user, with subscription. Some of you already heard of the website www.doorway.ru where you can download a bunch of everything. -

Improving Performance of Modern Peer-To-Peer Services

UMEA˚ UNIVERSITY Department of Computing Science Master Thesis Improving performance of modern Peer-to-Peer services Marcus Bergner 10th June 2003 Abstract Peer-to-peer networking is not a new concept, but has been resurrected by services such as Napster and file sharing applications using Gnutella. The network infrastructure of todays networks are based on the assumption that users are simple clients making small requests and receiving, possibly large, replies. This assumption does not hold for many peer-to-peer services and hence the network is often used inefficiently. This report investigates the reasons behind this waste of resources and looks at various ways to deal with these issues. Focusing mainly on file shar- ing various attempts are presented and techniques and suggestions on how improvements can be made are presented. The report also looks at the implementation of peer-to-peer services and what kind of problems need to be solved when developing a peer-to-peer application. The design and implementation of a peer-to-peer framework that solves common problems is the most important contribution in this area. Looking at other peer-to-peer services conclusions regarding peer-to-peer in general can be made. The thesis ends by summarizing the solutions to some of the flaws in peer-to-peer services and provides guidelines on how peer-to-peer services can be constructed to work more efficiently. Contents Preface i About this report . i About the author . i Supervisors . ii Typographical conventions . ii Software used . iii Acknowledgments . iii 1 Requirements 1 1.1 Summary of requirements . -

10Th Slide Set Cloud Computing

Centralized, Pure and Hybrid P2P Distributed Hash Table Bitcoins P2PTV P2P and Cloud 10th Slide Set Cloud Computing Prof. Dr. Christian Baun Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences (1971–2014: Fachhochschule Frankfurt am Main) Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering [email protected] Prof. Dr. Christian Baun – 10th Slide Set Cloud Computing – Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences – WS1819 1/60 Centralized, Pure and Hybrid P2P Distributed Hash Table Bitcoins P2PTV P2P and Cloud Agenda for Today Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Fundamentals Fields of application Centralized P2P Napster Pure P2P Gnutella version 0.4 Hybrid P2P Gnutella version 0.6 FastTrack BitTorrent Distributed hash table Bitcoins P2PTV Wuala P2P and Cloud Prof. Dr. Christian Baun – 10th Slide Set Cloud Computing – Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences – WS1819 2/60 Centralized, Pure and Hybrid P2P Distributed Hash Table Bitcoins P2PTV P2P and Cloud Peer-to-Peer – Fundamentals A Peer-to-Peer system is a network of equal nodes Node are called Peers Nodes provide access to resources to each other Each node is Client and Server at the same time Can be used to build up decentralized working environments Andy Oram „A Peer-to-Peer system is a self-organizing system of equal, autonomous entities (peers) which aims for the shared usage of distributed resources in a networked environment avoiding central services.“ Spelling A standard spelling does not exist. Often, Peer-to-Peer is also written P2P or Peer-2-Peer (with or without dashes) Prof. Dr. Christian Baun – 10th Slide -

Improving Gnutella Protocol: Protocol Analysis and Research Proposals

Improving Gnutella Protocol: Protocol Analysis And Research Proposals Igor Ivkovic Software Architecture Group (SWAG) Department of Computer Science University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Canada +1 (519) 888-4567 x3088 [email protected] ABSTRACT phenomenon called Napster [1]. Fanning envisioned This paper presents an analysis of the Gnutella protocol, a Napster as a service that allows users of his system to list type of the peer-to-peer networking model, that currently the MP3-encoded music files that they are willing to share provides decentralized file-sharing capabilities to its users. and let other users download them through the Napster The paper identifies the open problems that are related to network. The central computer would then at all times have the protocol and proposes strategies that can be used to an up-to-date master list of files that people are willing to resolve them. share, and the list would be updated by the users’ software as they log on and off the system. Initially, the paper explains the basics of the peer-to-peer networking, and then compares the two types of this Fanning’s idea required an network infrastructure of networking standard: centralized and decentralized. The servers for the centralized peer-to-peer data access and data Gnutella protocol is classified as a decentralized model, storage, and a corresponding bandwidth for allowing a and its characteristics and specifications are described large number of user connections. After his idea is accordingly. implemented, Napster at one point attracted over 30 million users with over 800 thousand of them accessing the The issues that are outstanding for the protocol are listed network simultaneously [1]. -

On the Long-Term Evolution of the Gnutella Network

On the Long-term Evolution of the Gnutella Network Amir H. Rasti, Daniel Stutzbach, Reza Rejaie University of Oregon Abstract the impact of a newly introduced feature de- pends on two factors: (i) the coherency (or com- The popularity of Peer-to-Peer (P2P) file sharing patibility) of features across different brands of applications has significantly increased during client software and (ii) the penetration rate and the past few years. To accommodate the increas- availability of a feature throughout the system. ing user population, developers gradually evolve As new features become available, users upgrade their client software by introducing new features, their client software and the new features grad- such as a two-tier overlay topology. The evolu- ually spread throughout the system. Therefore, tion of these P2P systems primarily depends on the penetration rate of new features primarily (i) coherency across different implementations depends on which brands implement the feature and (ii) the availability of these feature among and the ability and willingness of users to up- clients throughout the system. grade. This paper sheds some light on the evolution In this paper, we examine the evolution of of client and overlay characteristics in the Gnu- the Gnutella network during the past year over tella network during a one year period over which which its overall population has tripled to more it tripled in size, exceeding two million concur- than two million simultaneous peers. Toward rent peers. Our results show several interesting this end, we explore the evolution of the Gnu- trends including (i) most users quickly upgrade tella network across two related angles: their software which provides great flexibility for • developers to react to changes and (ii) as the sys- Client Characteristics that include changes tem has grown in size the top-level overlay has in the overall population, the distribution remained properly connected but there is grow- across different geographic regions, and the ing imbalance between the two levels. -

P2P Filesharing Population Tracking Based on Network Flow Data

P2P Filesharing Population Tracking Based on Network Flow Data Arno Wagner, Thomas D¨ubendorfer, Lukas Hammerle,¨ Bernhard Plattner Contact: [email protected] Communication Systems Laboratory Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich) Outline 1. Motivation 2. Setting 3. The PeerTracker 4. Validation by Polling 5. Comments on Legal Aspects 6. Conclusion Arno Wagner, ETH Zurich, ICISP 2006 – p.1 Contributors Philipp Jardas, ”P2P Filesharing Systems: Real World NetFlow Traffic Characterization”, Barchelor Thesis, ETH Zürich, 2004 Lukas Hämmerle, ”P2P Population Tracking and Traffic Characterization of Current P2P file-sharing Systems”, Master Thesis, ETH Zürich, 2004 Roger Kaspar, ”P2P File-sharing Traffic Identification Method Validation and Verification”, Semester Thesis, ETH Zürich, 2005 PDFs available from http://www.tik.ee.ethz.ch/~ddosvax/sada/ Arno Wagner, ETH Zurich, ICISP 2006 – p.2 Motivation P2P traffic forms a large and dynamic part of the overall network traffic Identification of P2P traffic allows P2P anomaly detection Identification of P2P traffic allows better analysis of other traffic Arno Wagner, ETH Zurich, ICISP 2006 – p.3 The DDoSVax Project http://www.tik.ee.ethz.ch/~ddosvax/ Collaboration between SWITCH (www.switch.ch, AS559) and ETH Zurich (www.ethz.ch) Aim (long-term): Near real-time analysis and countermeasures for DDoS-Attacks and Internet Worms Start: Begin of 2003 Funded by SWITCH and the Swiss National Science Foundation Arno Wagner, ETH Zurich, ICISP 2006 – p.4 DDoSVax Data Source: SWITCH The Swiss Academic And Research Network .ch Registrar Links most Swiss Universities and CERN Carried around 5% of all Swiss Internet traffic in 2003 Around 60.000.000 flows/hour Around 300GB traffic/hour Flow archive (unsampled) since May 2003 Arno Wagner, ETH Zurich, ICISP 2006 – p.5 What is a ”Flow”? In the DDoSVax-Project: CISCO NetFlow v5. -

Intro to Crypto Sci-Club Notes

Intro to Crypto Sci-Club Notes April 25, 2019 Abstract Notes preparing for sci-club crypto-blockchain presentation. List of possible topics Start with history, review of core tech concepts. Finish with applications. • First large-scale use of blockchain was in WWII Enigma coding machines. Maybe explain how these work? • Concept of mixing/entropy. Concept of mixing at different time-scales (slow, fast). • Public key crypto mathematics theory. • Public key crypto examples: PGP/GPG, x.509 certs, SSL/https, onion routing described at general level • Crypto at a detailed level: ratchet, double ratchet, forward secrecy, what is it for, how does this work? • Nonce; using nonces for secret boxes; all secret boxes must have a different nonce else there is no forward secrecy • Merkle tree (hash tree): it doesn’t have to be an actual chain; it can be a tree of chains, leading up to a signed root. Thus the dat:// protocol and btrfs, zfs – Bitcoin has merkle trees inside of it; where? why? • Git as a blockchain, and why it was needed - to prevent source code fraud (real, not imagined - intentional covert, secret insertion of corruption/bugs into Linux kernel by unknown actors (possibly NSA??)) – Git is a blockchain of commits. – Each commit is a Merkle tree of file-objects (blobs) that captures the state of that filesystem tree at that particular moment. • File sharing, sleepycat/napster, 1 – Gnutella, BearShare, LimeWire, Shareaza, all use tiger tree hash • torrent architectures (bittorrent tracker is example of DHT) • Other weirdo crypto ideas: death-lottery. • Forking and fork resolution. A fork prevents maintanance of state (e.g. -

Tackling the Illegal Trade in the Digital World

Cyber-laundering: dirty money digitally laundered- Tackling the illegal trade in the Digital world Graham Butler Special Presentation to the Academy of European Law Budapest – March 2016 Co-funded by the Justice Programme of the European Union 2014-2020 Graham Butler – Chairman Bitek Group of Companies © 2016 Tackling the illegal trade in the Digital world Supporting the Cyber-Security agenda ERA (Academy of European Law) – Lisbon / Trier / Sofia / Brussels Address: Threats to Financial Systems – VoIP, lawful intercept, money laundering CTO (Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation) London Address: Working group on strategic development for 2016-2020 ITU High level Experts Group – Cybersecurity Agenda – Geneva (United Nations) Address: VoIP and P2P Security – Lawful Intercept ENFSC (European Network Forensic and Security Conference) - Maastricht Address: Risks of P2P in Corporate Networks CTITF (Counter Terrorism Implementation Taskforce) - Seattle Address: Terrorist use of encrypted VoIP/P2P protocols - Skype Norwegian Police Investigation Section - Oslo Address: Next Generation Networks – VoIP Security (fixed and mobile networks) IGF (Internet Governance Forum) – Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt Address: Threats to Carrier Revenues and Government Taxes – VoIP bypass EastWest Institute Working Group on Cybercrime - Brussels / London Working Groups: Global Treaty on Cybersecurity / Combating Online Child Abuse CANTO (Caribbean Association of National Telecoms Org) – Belize / Barbados Address: Reversing Declines in Telecommunications Revenue ICLN (International Criminal Law Network) - The Hague Address: Cybercrime Threats to Financial Systems CIRCAMP (Interpol / Europol) - Brussels Working Groups: Online Child Abuse – The Fight Against illegal Content Graham Butler – President and CEO Bitek © 2013 1 Tackling the illegal trade in the Digital world The evolution of interception - circuit switched networks 1. Threat to National Security 3. -

Forensic Investigation of Peer-To-Peer File Sharing Networks

digital investigation 7 (2010) S95eS103 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/diin Forensic investigation of peer-to-peer file sharing networks Marc Liberatore a,*, Robert Erdely c, Thomas Kerle b, Brian Neil Levine a, Clay Shields d a Dept. of Computer Science, Univ. of Massachusetts Amherst, Computer Science Building, 140 Governors Drive, Amherst, MA 01003-9264, USA b Massachusetts State Police, USA c Pennsylvania State Police, USA d Dept. of Computer Science, Georgetown Univ., USA abstract The investigation of peer-to-peer (p2p) file sharing networks is now of critical interest to law enforcement. P2P networks are extensively used for sharing and distribution of contraband. We detail the functionality of two p2p protocols, Gnutella and BitTorrent, and describe the legal issues pertaining to investigating such networks. We present an analysis of the protocols focused on the items of particular interest to investigators, such as the value of evidence given its provenance on the network. We also report our development of RoundUp, a tool for Gnutella investigations that follows the principles and techniques we detail for networking investigations. RoundUp has experienced rapid acceptance and deployment: it is currently used by 52 Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) Task Forces, who each share data from investigations in a central database. Using RoundUp, since October 2009, over 300,000 unique installations of Gnutella have been observed by law enforcement sharing known contraband in the the U.S. Using leads and evidence from RoundUp, a total of 558 search warrants have been issued and executed during that time. ª 2010 Digital Forensic Research Work Shop.