Arxiv:1601.00451V1 [Physics.Atom-Ph] 4 Jan 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Pumping of Stored Atomic Ions (*)

Ann. Phys. Fr. 10 (1985) 737-748 DhCEMBRE 1985, PAGE 131 Optical pumping of stored atomic ions (*) D. J. Wineland, W. M. Itano, J. C. Bergquist, J. J. Bollinger and J. D. Prestage Time and Frequency Division, National Bureau of Standards, Boulder, Colorado 80303, U.S.A. Resume. - Ce texte discute les expkriences de pompage optique sur des ions atomiques confints dans des pikges tlectromagnttiques. Du fait de la faible relaxation et des dtplacements d'energie trbs petits des ions confine$ on peut obtenir une trb haute rtsolution et une tres grande prkision dans les exptriences de pompage optique associt a la double rtsonance. Dans la ligne de l'idee de Kastler de (( lumino-rtfrigtration H (1950), l'tnergie cinttique des niveaux des ions confines peut Ctre pompke optiquement. Cette technique, appelee refroidissement laser, rtduit sensiblement les dtplacements de frtquence Doppler dans les spectres. Abstract. - Optical pumping experiments on atomic ions which are stored in ekG tromagnetic (( traps )) are discussed. Weak relaxation and extremely small energy shifts of the stored ions lead to very high resolution and accuracy in optical pumping- double resonance experiments. In the same spirit of Kastler's proposal for (( lumino refrigeration )) (1950), the kinetic energy levels of stored ions can be optically pumped. This technique, which has been called laser cooling significantly reduces Doppler frequency shifts in the spectra. 1. Introduction. For more than thirty years, the technique of optical pumping, as originally proposed by Alfred Kastler [I], has provided information about atomic structure, atom-atom interactions, and the interaction of atoms with external radiation. This technique continues today as one of the primary methods used in atomic physics. -

Optical Pumping: a Possible Approach Towards a Sige Quantum Cascade Laser

Institut de Physique de l’ Universit´ede Neuchˆatel Optical Pumping: A Possible Approach towards a SiGe Quantum Cascade Laser E3 40 30 E2 E1 20 10 Lasing Signal (meV) 0 210 215 220 Energy (meV) THESE pr´esent´ee`ala Facult´edes Sciences de l’Universit´ede Neuchˆatel pour obtenir le grade de docteur `essciences par Maxi Scheinert Soutenue le 8 octobre 2007 En pr´esence du directeur de th`ese Prof. J´erˆome Faist et des rapporteurs Prof. Detlev Gr¨utzmacher , Prof. Peter Hamm, Prof. Philipp Aebi, Dr. Hans Sigg and Dr. Soichiro Tsujino Keywords • Semiconductor heterostructures • Intersubband Transitions • Quantum cascade laser • Si - SiGe • Optical pumping Mots-Cl´es • H´et´erostructures semiconductrices • Transitions intersousbande • Laser `acascade quantique • Si - SiGe • Pompage optique i Abstract Since the first Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) was realized in 1994 in the AlInAs/InGaAs material system, it has attracted a wide interest as infrared light source. Main applications can be found in spectroscopy for gas-sensing, in the data transmission and telecommuni- cation as free space optical data link as well as for infrared monitoring. This type of light source differs in fundamental ways from semiconductor diode laser, because the radiative transition is based on intersubband transitions which take place between confined states in quantum wells. As the lasing transition is independent from the nature of the band gap, it opens the possibility to a tuneable, infrared light source based on silicon and silicon compatible materials such as germanium. As silicon is the material of choice for electronic components, a SiGe based QCL would allow to extend the functionality of silicon into optoelectronics. -

Optical Pumping

Optical Pumping MIT Department of Physics (Dated: February 17, 2011) Measurement of the Zeeman splittings of the ground state of the natural rubidium isotopes; measurement of the relaxation time of the magnetization of rubidium vapor; and measurement of the local geomagnetic field by the rubidium magnetometer. Rubidium vapor in a weak (∼.01- 10 gauss) magnetic field controlled with Helmholtz coils is pumped with circularly polarized D1 light from a rubidium rf discharge lamp. The degree of magnetization of the vapor is inferred from a differential measurement of its opacity to the pumping radiation. In the first part of the experiment the energy separation between the magnetic substates of the ground-state hyperfine levels is determined as a function of the magnetic field from measurements of the frequencies of rf photons that cause depolarization and consequent greater opacity of the vapor. The magnetic moments of the ground states of the 85Rb and 87Rb isotopes are derived from the data and compared with the vector model for addition of electronic and nuclear angular momenta. In the second part of the experiment the direction of magnetization is alternated between nearly parallel and nearly antiparallel to the optic axis, and the effects of the speed of reversal on the amplitude of the opacity signal are observed and compared with a computer model. The time constant of the pumping action is measured as a function of the intensity of the pumping light, and the results are compared with a theory of competing rate processes - pumping versus collisional depolarization. I. PREPARATORY PROBLEMS II. INTRODUCTION 1. With reference to Figure 1 of this guide, estimate A. -

Optical Pumping 1

Optical Pumping 1 OPTICAL PUMPING OF RUBIDIUM VAPOR Introduction The process of optical pumping is a beautiful example of the interaction between light and matter. In the Advanced Lab experiment, you use circularly polarized light to pump a particular level in rubidium vapor. Then, using magnetic fields and radio-frequency excitations, you manipulate the population of the pumped state in a manner similar to that used in the Spin Echo experiment. You will determine the energy separation between the magnetic substates (Zeeman levels) in rubidium as well as determine the Bohr magneton and observe two-photon transitions. Although the experiment is relatively simple to perform, you will need to understand a fair amount of atomic physics and experimental technique to appreciate the signals you witness. A simple example of optical pumping Let’s imagine a nearly trivial atom: no nuclear spin and only one electron. For concreteness, you can think of the 4He+ ion, which is similar to a Hydrogen atom, but without the nuclear spin of the proton. Its ground state is 1S1=2 (n = 1,S = 1=2,L = 0, J = 1=2). Photon absorption can excite it to the 2P1=2 (n = 2,S = 1=2,L = 1, J = 1=2) state. If you place it in a magnetic field, the energy levels become split as indicated in Figure 1. In effect, each original level really consists of two levels with the same energy; when you apply a field, the “spin up” state becomes higher in energy, the “spin down” lower. The spin energy splitting is exaggerated on the figure. -

Spin Coherence and Optical Properties of Alkali-Metal Atoms in Solid Parahydrogen

Spin coherence and optical properties of alkali-metal atoms in solid parahydrogen Sunil Upadhyay,1 Ugne Dargyte,1 Vsevolod D. Dergachev,2 Robert P. Prater,1 Sergey A. Varganov,2 Timur V. Tscherbul,1 David Patterson,3 and Jonathan D. Weinstein1, ∗ 1Department of Physics, University of Nevada, Reno NV 89557, USA 2Department of Chemistry, University of Nevada, Reno NV 89557, USA 3Broida Hall, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, California 93106, USA We present a joint experimental and theoretical study of spin coherence properties of 39K, 85Rb, 87Rb, and 133Cs atoms trapped in a solid parahydrogen matrix. We use optical pumping to prepare the spin states of the implanted atoms and circular dichroism to measure their spin states. Optical pumping signals show order-of-magnitude differences depending on both matrix growth conditions ∗ and atomic species. We measure the ensemble transverse relaxation times (T2) of the spin states ∗ of the alkali-metal atoms. Different alkali species exhibit dramatically different T2 times, ranging 87 2 39 from sub-microsecond coherence times for high mF states of Rb, to ∼ 10 microseconds for K. ∗ These are the longest ensemble T2 times reported for an electron spin system at high densities 16 −3 (n & 10 cm ). To interpret these observations, we develop a theory of inhomogenous broadening of hyperfine transitions of 2S atoms in weakly-interacting solid matrices. Our calculated ensemble transverse relaxation times agree well with experiment, and suggest ways to longer coherence times in future work. I. INTRODUCTION In this work, we compare the optical pumping prop- ∗ erties and ensemble transverse spin relaxation time (T2) Addressable solid-state electron spin systems are of in- for potassium, rubidium, and cesium in solid H2. -

Optical Pumping and the Hyperfine Structure of Rubidium 87

Optical Pumping and the Hyperfine Structure of Rubidium 87 Laboratory Manual for Physics 3081 Thomas Dumitrescu∗, Solomon Endlich† May 2007 Abstract In this experiment you will learn about the powerful experimental technique of optical pumping, and apply it to investigate the hyperfine structure of Rubidium in an applied external magnetic field. The main goal of the experiment is to measure the hyperfine splitting of the ground state of Rubidium 87 at zero external magnetic field. Note: In this lab manual, Gaussian units are used throughout. See [4] for the relation between Gaussian and SI units. ∗email: [email protected] †email: [email protected] 1 1 Hyperfine Structure of Rubidium In this experiment you will study the optical pumping of Rubidium in an external magnetic field to determine its hyperfine structure. In the following, we give a brief outline of the hyperfine structure of Rubidium and its Zeeman splitting in an external magnetic field. The main goal of this section is to motivate the Breit-Rabi formula, which gives the Zeeman splitting of the Hyperfine levels. For a thorough and enlightening discussion of these topics we refer to the excellent article by Benumof [1]. The ground state of alkali atoms - of which Rubidium is one - consists of a number of closed shells and one s-state valence electron in the next shell. Recall that the total angular momentum of a closed atomic shell is zero, so the total angular momentum of the Rubidium atom is the sum of three angular momenta: the orbital and spin angular momenta L and S of the valence electron, and the nuclear angular momentum I. -

Optical Pumping

California Institute of Technology Physics 77 Optical Pumping Eric D. Black October 7, 2014 Sometimes you want to magnetize a gas, to align all of the little mag- netic moments of the gas atoms in the same direction. You might plan to have somebody inhale the polarized gas, then look at the insides of their lungs using magnetic-resonance imaging, or you might want to investigate the electronic level structure of the gas atoms, and polarizing them is the first step in a spectroscopy program. There are lots of times, in a modern research lab, where you want a polarized gas, and the usual way to produce it is by optical pumping. In this lab you will learn basic optical pumping, and you will practice it on a gas of Rubidium atoms. Rubidium is a fairly simple atom. Its electronic structure closely approximates that of a Hydrogen atom, so we can get a pretty good theoretical understanding. However, even in Hydrogen-like atoms there are interesting effects that can be investigated spectroscopically using optical pumping, and we will do that in this lab. 1 Prelab I 1.1 Rubidium's atomic energy level structure Rubidium in its atomic state has just one valence electron and can be well approximated by a one-electron-atom model. Its nuclear properties are dif- ferent from Hydrogen, however, and this will give it a different energy-level structure. There are two commonly-occurring isotopes of Rubidium in na- ture, 85Rb, with a natural abundance of 72%, and 87Rb, with an abundance of 28%. In this section you will learn all about 87Rb, but the structure of 85Rb follows the same general priciples. -

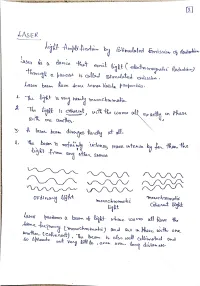

Unit 4 LASERS By. Dr. M. Z. Ansari

Differences between Stimulated and spontaneous emission of radiation S.no Stimulated Emission Spontaneous emission 1 An atom in the excited state is induced to The atom in the excited state returns to the return to the ground state , thereby resulting ground state thereby emitting a photon, in two photons of same frequency and without any external inducement is called energy is called Stimulated emission Spontaneous emission 2 The emitted photons move in the same The emitted photons move in all directions direction and is highly directional and are random 3 The radiation is highly intense , The radiation is less intense and is monochromatic and coherent incoherent. 4 The photons are in phase, there is a constant The photons are not in phase (i.e.) there is phase difference. no phase relationship between them The rate of transition is given by The rate of transition is given by R21 (St) = B21 u() N2 R21 (Sp) = A21 N2 Population Inversion: Population Inversion creates a situation in which the number of atoms in higher energy state is more than that in the lower energy state. Usually at thermal equilibrium, the number of atoms N2 i.e., the population of atoms at excited state is much lesser than the population of the atoms at ground state N1 that is N1 > N2. The Phenomenon of making N2 > N1 i.e, the number of particles N2 more in higher energy level than the number of particles N1 in lower energy level is known as Population Inversion or inverted population. The states of system, in which the population of higher energy state is more in compression to the population of lower energy state are called negative temperature states. -

Optical Pumping of Rubidium

Instru~nentsDesigned for Teaching OPTICAL PUMPING OF RUBIDIUM Guide to the Experiment INSTRUCTOR'S MANUAL A PRODUCT OF TEACHSPIN, INC. $.< Teachspin, Inc. 45 Penhurst Park, Buffalo, NY 14222-10 13 h. (716) 885-4701 or www.teachspin.com Copyright O June 2002 4 rq hc' $ t,q \I Table of Contents SECTION PAGE 1. Introduction 2. Theory A. Structure of alkali atoms B. Interaction of an alkali atom with a magnetic field C. Photon absorption in an alkali atom D. Optid pumping in rubidium E. Zero field transition F. Rf spectroscopy of IZbgs and ~b*' G. Transient effects 3. Apparatus A. Rubidium discharge lamp B. ~etktor c. optics D. Temperature regulation E. Magnetic fields F. Radio frequency - 4. Experiments A. Absorption of Rb resonance radiation by atomic Rb 4-1 B. Low field resonances 4-6 C. Quadratic Zeeman Effect 4-12 D. Transient effects 4-17 5. Getting Started 5-1 INTRODUCTION The term "optical pumping" refers to a process which uses photons to redistribute the states occupied by a collection of atoms. For example, an isolated collection of atoms in the form of a gas will occupy their available energy states, at a given temperature, in a way predicted by standard statistical mechanics. This is referred to as the thermal equilibrium distribution. But the distribution of the atoms among these energy states can be radically altered by the clever application of what is called "resonance radiation." Alfied Kastler, a French physicist, introduced modem optical pumping in 1950 and, in 1966, was awarded a Nobel Prize "jhr the discovery and development of optical methods for stu&ing hertzian resonances in atoms. -

Optical Pumping Physics 111B: Advanced Experimentation Laboratory University of California, Berkeley

OPT - Optical Pumping Physics 111B: Advanced Experimentation Laboratory University of California, Berkeley Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Before the first day of lab2 3 Objectives 3 4 Background 4 4.1 Atomic structure........................................... 4 4.2 Rb in a magnetic field: The Breit-Rabi formula.......................... 5 4.3 Optical pumping........................................... 7 4.4 Optically detected magnetic resonance............................... 8 5 Experimental setup 8 6 Experimental procedure 12 6.1 Inspecting and turning on the experiment............................. 12 6.2 First observation of ODMR: Fixing the current and sweeping the frequency........... 12 6.3 Finding good settings for the bulb temperature.......................... 14 6.4 Current modulation/lock-in detection of the resonance frequency................ 14 6.5 Timescales for optical pumping using square wave amplitude modulation of the rf field . 17 7 Analysis 17 References 19 1 1 Introduction One of the great early successes of quantum mechanics was its use to describe the structure of atoms and molecules. As is now well-known, the internal structure of atoms and molecules can be described by a set of quantum states. In the case of an atom, these quantum states tell us what is the state of motion of electrons around the nucleus, of the internal spin of those electrons, and also of the internal spin of the nucleus. In the case of molecules, quantum states also tell us about the relative motion of nuclei. Quantum mechanics also tells us which of these quantum states are also states of definite total energy { these are the energy eigenstates. A powerful way of measuring the energies of atomic quantum states, or, more properly, the energy differences between two energy levels, is through spectroscopy. -

Cross Polarization from Laser-Polarized Solid Xenon to 13C02 by Low-Field Thermal Mixing

Volume 205, number 2,3 CHEMICAL PHYSICS LETTERS 9 April 1993 Cross polarization from laser-polarized solid xenon to 13C02 by low-field thermal mixing C.R. Bowers, H. W. Long, T. Pietrass, H.C. Gaede and A. Pines Malerials Sciences Division, Luwrence Berkeley Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, US4 and Department of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94 720, USA Received 30 December 1992 The first observation of nuclear spin polarization enhancement in a molecular species by coupling to laser-polarized xenon is reported. The spins of ‘%Oz were cooled by inclusion into the xenon solid followed by thermal mixing in magnetic fields corn- parable to the heteronuclear dipolar interactions. High-field NMR detection yielded enhancement factors of up to 200. Moreover, a change in the sense of the helicity of the optical pumping light results in a sign reversal of the spin temperature and hence an inversion of the 13CNMR signal. Over thirty years ago, it was demonstrated [ 1] that provided optical pumping fields of 160-200 mW/ the angular momentum of optical photons could be cm* at a wavelength of 794.7 nm (corresponding to transferred to rare gas nuclear spins by optical the D1 line of Rb). The remainder of the optical pumping and spin exchange with alkali metal atoms. pumping apparatus has been described previously Spin exchange to xenon is particularly efficient due [ 61 except with the modification that the pumping to strong van der Waals complex formation [ 21. Xe- cell was connected by glassware to an Gshapcd NMR non nuclear spin polarizations as high as 35% can be sample tube located outside the fringe field of the su- obtained in rubidium xenon mixtures using com- perconducting magnet. -

Chapter 1: Introduction

_______________________________________________________________________________Chapter 1: Introduction CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION This Chapter is an introduction to solid-state lasers and solid-state laser materials. In particular it is discussed, active media (host materials and active ions), pump sources and laser cavities that were used in this Thesis. Included is a historical overview of the laser action of Yb3+ in 3+ monoclinic KRE(WO4)2 and some references to the laser action of Er in KRE(WO4)2. Following this introduction it is outlined the main objectives of this work. 1 _______________________________________________________________________________Chapter 1: Introduction Table of contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Overview of Solid-State Lasers (SSL) 1.1.1 Stimulated emission 1.1.2 Continuos-wave (CW) and Pulsed lasers 1.1.3 Solid-State Laser components 1.1.3.1 Active medium 1.1.3.2 Pump sources 1.1.3.3 Laser cavity 1.1.4 Issues in Laser design 1.2 Overview of Solid-State Laser Materials 1.2.1 Host Materials 1.2.1.1 Monoclinic tungstates 1.2.2 Active Ions 1.2.2.1 Ytterbium (Yb3+) 1.2.2.2 Erbium (Er3+) 1.2.2.3 Energy transfer between Yb3+ and Er3+ ions 3+ 3+ 1.3 Overview of the Yb and Er -doped KRE(WO4)2 lasers Objectives 2 _______________________________________________________________________________Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Overview of Solid-State Lasers (SSL) The principle of the laser was first known in 1917, when Einstein described the theory of stimulated emission. However, it was not until the late 1940s that engineers began to use this principle for practical purposes.