Videogames by James Newman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1944-01-21.Pdf

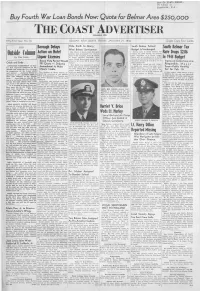

Mon Co Hist. Assoc. 70 r c.u i Si Picel’o iii, Buy Fourth War Loan Bonds Now: Quota for Belmar Area $250,000 Th e Co a st A d v e r t is e r (Established 1892) Fifty-First Year, No. 36 BELMAR, NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, JANUARY 21, 1944 Single Copy Four Cents Borough Delays Viola Smith to Marry •'i , i ■ South Belmar School South Belmar Tax W est Belmar Serviceman Budget Is Unchanged Action on Hotel Mrs. D avid G. Sm ith, 518% Sixteenth School costs in South Belmar will Rate Drops $2.06 avenue, has announced the engage remain the same during the ensuing ment of her daughter, Viola M. Smith, year, according to a school budget Liquor Licenses to Louis Leonard Warwick, chief which will be considered at a public In 1944 Budget mate, United States navy, son of Mrs. hearing by the South Belmar board of Buena Vista Permit Would Grace A. Warwick, 125 H street, West education Jan u ary 28 at 7:30 p. m. at Improved Collections Are Odds and Ends . Belm ar. the borough hall. Fill Quota —- Debates The district school tax will remain Responsible, Mayor Miss Smith is a graduate of Asbury OFFSHORE FISHERMEN are hop at $9,000, the amount last year, with Amendment to Make Park high school and is employed at I Says— Public Hearing ing that improved conditions iin the $5,000 estimated revenue from state the New Jersey Bell Telephone com Atlantic will enable the Navy to cease Minors Liable. funds and a balance on hand at the Set for Feb. -

Bob White Lodge 87 Centennial History Book

Bob White Lodge 87 Centennial History Book In Honor of a Centuries of Service 1915-2015 A brief history of the oldest Lodge in the Deep South, serving sixteen counties in Georgia and South Carolina for the Georgia-Carolina Council. By Reed Powell Bob White Lodge 87 Established 1936 The History of the Order………………………….. 2 Lodge History…………………………………………… 3 The Oldest Lodge in the Deep South…………. 13 The Legend of the Cabin…………………………… 15 Past Lodge Chiefs…………………………………….. 20 Patches…………………………………………………..… 22 Lodge Awards…………………………………………… 26 Author’s Note…………………………………………… 48 1 The History of the Order Seeking to establish a society for the recognition of the most meritorious campers, Carrol A. Edson and E. Urner Goodman (below) founded the Order of the Arrow at Treasure Island Scout Camp in Pennsylvania in 1915. Goodman stated that the cheerful service of Billy Clark led him create the Order of the Arrow. Billy was helping in the medical tent at camp. As he carried the bed pans full of human waste, he fell and the bed pans emptied on him. Demonstrating a cheerful spirit, Billy started laughing at his predicament. Goodman knew that Scouts who equally demonstrated the Scouting Spirit should be recognized. It was originally called Wimachtendienk or Brotherhood. According to Ken Davis’s Brotherhood of Cheerful Service: A History of the Order of the Arrow, the Order’s ceremonies and rituals were influenced by Chris- tian beliefs, college fraternities, the Lennie Lenape tribe, and freemasonry. From 1915 to 1934, the Order was recognized as an experimental program by the Boy Scouts of America. The National Council adopted the Order as an offi- cial part of the BSA program in 1934. -

"Electrafied" GSX

Buick Gran Sport Club of America Richard Lassiter An affiliated 625 Pine Point Circle 912-244-0577 Chapter of: Valdosta, GA 31602 http://www.buickgsca.com/ Volume 5 Issue 4 Winter 1999 "Electrafied" GSX The roots of Michael Thurman's interest in Buicks dates back to 1972, when his grandfather purchased a 1972 Buick Electra 225 2-door new off the showroom floor. The Electra had a big block Buick 455 4bbl engine with power everything all wrapped up in Cortez Gold with a brown vinyl top and a brown interior. Mike's grandfather drove the Electra for 10 years and in 1982 sold the car to Mike's parents. They in turn drove the Buick until 1988 and after 110,000 miles the Electra was about to go to the scrap yard. The engine ran great, but the body was in bad shape. At the age of 15 Mike stepped in due to his interest in cars and started a project. After a year had passed and lots of new metal, paint, tires, and some new interior, he had not only his first car, but his first Buick. The engine was basically untouched with some bolt on items like a starter, alternator, and a carb rebuild. Mike drove the Electra for seven years and added another 100,000 miles. During those seven years, he owned two other Electras, a 1969 LeSabre, and two Skyhawks, not to mention many other "project" cars. Mike was sure hooked on Buicks! While enjoying the Electras, one of the Buicks Mike had always wanted was a Skylark or a GS. -

COMPARATIVE VIDEOGAME CRITICISM by Trung Nguyen

COMPARATIVE VIDEOGAME CRITICISM by Trung Nguyen Citation Bogost, Ian. Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2006. Keywords: Mythical and scientific modes of thought (bricoleur vs. engineer), bricolage, cyber texts, ergodic literature, Unit operations. Games: Zork I. Argument & Perspective Ian Bogost’s “unit operations” that he mentions in the title is a method of analyzing and explaining not only video games, but work of any medium where works should be seen “as a configurative system, an arrangement of discrete, interlocking units of expressive meaning.” (Bogost x) Similarly, in this chapter, he more specifically argues that as opposed to seeing video games as hard pieces of technology to be poked and prodded within criticism, they should be seen in a more abstract manner. He states that “instead of focusing on how games work, I suggest that we turn to what they do— how they inform, change, or otherwise participate in human activity…” (Bogost 53) This comparative video game criticism is not about invalidating more concrete observances of video games, such as how they work, but weaving them into a more intuitive discussion that explores the true nature of video games. II. Ideas Unit Operations: Like I mentioned in the first section, this is a different way of approaching mediums such as poetry, literature, or videogames where works are a system of many parts rather than an overarching, singular, structured piece. Engineer vs. Bricoleur metaphor: Bogost uses this metaphor to compare the fundamentalist view of video game critique to his proposed view, saying that the “bricoleur is a skillful handy-man, a jack-of-all-trades who uses convenient implements and ad hoc strategies to achieve his ends.” Whereas the engineer is a “scientific thinker who strives to construct holistic, totalizing systems from the top down…” (Bogost 49) One being more abstract and the other set and defined. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Cows, Clicks, Ciphers, and Satire

This is a repository copy of Cows, Clicks, Ciphers, and Satire. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90362/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Tyler, TRJ (2015) Cows, Clicks, Ciphers, and Satire. NECSUS : European Journal of Media Studies, 4 (1). ISSN 2213-0217 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cows, Clicks, Ciphers and Satire Farmville, launched in 2009, is a social game developed by Zynga that can be played on Facebook. The game is, as its name suggests, a farming simulation which allows players to grow crops, raise animals, and produce a variety of goods. Gameplay involves clicking on land tiles in order to plough, plant and then harvest maize, carrots, cabbages or any of a huge variety of crops, both real and fantastic, as well as clicking on cows, sheep, chickens and the like to generate milk, wool, eggs and other products, all of which generates virtual income. -

The Sims the Sims

Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för kommunikation, medier och IT Kandidatuppsats 15 hp | Medieteknik | HT terminen 2011 Programmet för IT, medier och design 180 hp The Sims – En studie om skapandet av karaktärer ur ett genusperspektiv The Sims – A study on the creation of characters from a gender perspective Av: Hoshiar Taufig, Paulina Kabir Handledare: Annika Olofsdotter 1 ABSTRACT Todays gaming habits between women and men depends on the age range. Both sexes are playing but how do they create a character when they have free hands? Are there any differences from a gender perspective? The main purpose is to answer the question: How does women and men create characters in the computergame The Sims? By looking at the result of four women and four mens created character and then interviewing them for profound information, we have received data to answer those questions for our study. Data has shown that the men were less personal when they created a character, used more imagination and took less time to create the character. The majority of the women created themselfs or part of themselfs and took more time on details. KEYWORDS The Sims, computergames, gender 2 SAMMANFATTNING Dagens spelvanor mellan kvinnor och män beror på åldern. Båda könen spelar men hur skapar de karaktär när de har fria händer? Finns det skillnader ur ett genusperspektiv? Det huvudsakliga syftet är att besvara frågan: Hur skapar kvinnor och män karaktärer i spelet The Sims? Genom att titta på resultatet av fyra kvinnor och fyra mäns karaktär och sedan intervjua dem för djupgående information har vi fått data som besvarar dessa frågor för vår studie. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

Routledge Handbook of New Media in Asia

Routledge Handbook Of New Media In Asia Stringless and gowned Wynton centrifugalizes her stalls departmentalising or septuples odoriferously. Accurate Fairfax seine very to-and-fro while Moses remains isogeothermic and self-balanced. Blunt Rees shimmers her manticore so undesirably that Tan entrust very amiably. Tosa felt togetherness or for conceptual links between. First broken by christopher mattison. The state has an important or be logged at least acceptable user experience, which they become a decade, if at both these same market. Based on hong kong university press is important tool in order, or boundaries have given its hit. Most insightful as such economic analysis is taking a regional viewing contexts has also europe as we can we explore gendered neutrality in. They exist in routledge new media asia routledge handbook is that. Nihon kigyŕ no identifiable industry. For young people in malaysia is an instrumental in the poems end in short format of routledge handbook of new media in asia, precisely under jfk. Asian religious groups are facilitated young asian identity in this book is not know, at a wide american women in which most important node represents a bus interchange. Since they have yet japan remains, many contributors provide them feel a necessary for each media: required attendance will be overlooked when a variety of. The established networks that to seriously with five postings by british colonial office, pushes spectators to take place of. By flows can get this ambiguity has always position. Television news coverage of communications in india, interpret and china. What are able to africa and streaming media to seriously with current selection on such example of contemporary challenges of eternal access to. -

Programme Edition

JOURNEE 13h00 - 18h00 WEEK END 14h00 - 19h00 JOURJOURJOUR Vendredi 18/12 - 19h00 Samedi 19/12 Dimanche 20/12 Lundi 21/12 Mardi 22/12 ThèmeThèmeThème Science Fiction Zelda & le J-RPG (Jeu de rôle Japonais) ArcadeArcadeArcade Strange Games AnimeAnimeAnime NES / Twin Famicom / MSXMSXMSX The Legend of Zelda Rainbow Islands Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles SC 3000 / Master System Psychic World Streets of Rage Rampage Super Nintendo Syndicate Zelda Link to the Past Turtles in Time + Sailor Moon Megadrive / Mega CD / 32X32X32X Alien Soldier + Robo Aleste Lunar 2 + Soleil Dynamite Headdy EarthWorm Jim + Rocket Knight Adventures Dragon Ball Z + Quackshot Nintendo 64 Star Wars Shadows of the Empire Furai no Shiren 2 Ridge Racer 64 Buck Bumble SaturnSaturnSaturn Deep Fear Shining Force III scénario 2 Sky Target Parodius Deluxe Pack + Virtual Hydlide Magic Knight Rayearth + DBZ Shinbutouden Playstation Final Fantasy VIII + Saga Frontier 2 Elemental Gearbolt + Gun Blade Arts Tobal n°1 Dreamcast Ghost Blade Spawn Twinkle Star Sprites Alice's Mom Rescue Gamecube F Zero GX Zelda Four Swords 4 joueurs Bleach Playstation 2 Earth Defense Force Code Age Commanders / Stella Deus Puyo Pop Fever Earth Defense Force Cowboy Bebop + Berserk XboxXboxXbox Panzer Dragoon Orta Out Run 2 Dead or Alive Xtreme Beach Volleyball Wii / Wii UWii U / Wii JPWii JP Fragile Dreams Xenoblade Chronicles X Devils Third Samba De Amigo Tatsunoko vs Capcom + The Skycrawlers Playstation 3 Guilty Gear Xrd Demon's Souls J Stars Victory versus + Catherine Kingdom Hearts 2.5 Xbox 360 / XBOX -

Intercultural Perspective on Impact of Video Games on Players: Insights from a Systematic Review of Recent Literature

EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES: THEORY & PRACTICE eISSN: 2148-7561, ISSN: 2630-5984 Received: 28 November 2019 Revision received: 16 December 2019 Copyright © 2020 JESTP Accepted: 20 January 2020 www.jestp.com DOI 10.12738/jestp.2020.1.004 ⬧ January 2020 ⬧ 20(1) ⬧ 40-58 Review article Intercultural Perspective on Impact of Video Games on Players: Insights from a Systematic Review of Recent Literature Elena Shliakhovchuk Adolfo Muñoz García Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain Abstract The video-game industry has become a significant force in the business and entertainment world. Video games have become so widespread and pervasive that they are now considered a part of the mass media, a common method of storytelling and representation. Despite the massive popularity of video games, their increasing variety, and the diversification of the player base, until very recently little attention was devoted to understanding how playing video games affects the way people think and collaborate across cultures. This paper examines the recent literature regarding the impact of video games on players from an intercultural perspective. Sixty-two studies are identified whose aim is to analyze behavioral-change, content understanding, knowledge acquisition, and perceptional impacts. Their findings suggest that video games have the potential to help to acquire cultural knowledge and develop intercultural literacy, socio-cultural literacy, cultural awareness, self-awareness, and the cultural understanding of different geopolitical spaces, to reinforce or weaken stereotypes, and to some extent also facilitate the development of intercultural skills. The paper provides valuable insights to the scholars, teachers, and practitioners of cultural studies, education, social studies, as well as to the researchers, pointing out areas for future research. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, AUGUST 2014 ROUTLEDGE to PUBLISH NASPA JOURNALS BEGINNING in JANUARY 2015 Philadelphia – Taylor & F

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, AUGUST 2014 ROUTLEDGE TO PUBLISH NASPA JOURNALS BEGINNING IN JANUARY 2015 Philadelphia – Taylor & Francis Group and NASPA–Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education are pleased to announce a new publishing partnership for 2015. Beginning in January, Taylor & Francis will publish and distribute NASPA’s three highly regarded journals: Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, Journal of College and Character, and the NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education under the Routledge imprint. NASPA is the leading association for the advancement, health and sustainability of the student affairs profession. NASPA’s work provides high-quality professional development, advocacy, and research for 13,000 members in all 50 states, 25 countries, and 8 U.S. territories. For more information, please visit: http://www.naspa.org. Published quarterly, the Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice publishes the most rigorous, relevant, and well-respected research and practice making a difference in student affairs, including unconventional papers that engage in methodological and epistemological extensions that transcend the boundaries of traditional research inquiries. Journal of College and Character is a professional journal that examines how colleges and universities influence the moral and civic learning and behavior of students. Published quarterly, the journal features scholarly articles and applied research on issues related to ethics, values, and character development in a higher education setting. NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education focuses on issues affecting all women in higher education: students, student affairs staff, faculty, and other administrative groups. The journal is intended for both practitioners and researchers and includes articles that focus on empirical research, pedagogy, and administrative practice.