Hate Crimes, Crimes of Atrocity, and Affirmative Action in India and the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward an Understanding of Why People Discriminate: Evidence from a Series of Natural Field Experiments

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING OF WHY PEOPLE DISCRIMINATE: EVIDENCE FROM A SERIES OF NATURAL FIELD EXPERIMENTS Uri Gneezy John List Michael K. Price Working Paper 17855 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17855 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2012 We thank Gary Becker, James Heckman, and Steven Levitt for their discussions throughout the exploration process. Seminar participants at the 2012 ASSA meetings in Chicago also provided useful insights. Moshe Hoffman provided able research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Uri Gneezy, John List, and Michael K. Price. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Toward an Understanding of Why People Discriminate: Evidence from a Series of Natural Field Experiments Uri Gneezy, John List, and Michael K. Price NBER Working Paper No. 17855 February 2012 JEL No. C93,J71 ABSTRACT Social scientists have presented evidence that suggests discrimination is ubiquitous: women, nonwhites, and the elderly have been found to be the target of discriminatory behavior across several labor and product markets. Scholars have been less successful at pinpointing the underlying motives for such discriminatory patterns. We employ a series of field experiments across several market and agent types to examine the nature and extent of discrimination. -

Belgaum District Lists

Group "C" Societies having less than Rs.10 crores of working capital / turnover, Belgaum District lists. Sl No Society Name Mobile Number Email ID District Taluk Society Address 1 Abbihal Vyavasaya Seva - - Belgaum ATHANI - Sahakari Sangh Ltd., Abbihal 2 Abhinandan Mainariti Vividha - - Belgaum ATHANI - Uddeshagala S.S.Ltd., Kagawad 3 Abhinav Urban Co-Op Credit - - Belgaum ATHANI - Society Radderahatti 4 Acharya Kuntu Sagara Vividha - - Belgaum ATHANI - Uddeshagala S.S.Ltd., Ainapur 5 Adarsha Co-Op Credit Society - - Belgaum ATHANI - Ltd., Athani 6 Addahalli Vyavasaya Seva - - Belgaum ATHANI - Sahakari Sangh Ltd., Addahalli 7 Adishakti Co-Op Credit Society - - Belgaum ATHANI - Ltd., Athani 8 Adishati Renukadevi Vividha - - Belgaum ATHANI - Uddeshagala S.S.Ltd., Athani 9 Aigali Vividha Uddeshagala - - Belgaum ATHANI - S.S.Ltd., Aigali 10 Ainapur B.C. Tenenat Farming - - Belgaum ATHANI - Co-Op Society Ltd., Athani 11 Ainapur Cattele Breeding Co- - - Belgaum ATHANI - Op Society Ltd., Ainapur 12 Ainapur Co-Op Credit Society - - Belgaum ATHANI - Ltd., Ainapur 13 Ainapur Halu Utpadakari - - Belgaum ATHANI - S.S.Ltd., Ainapur 14 Ainapur K.R.E.S. Navakarar - - Belgaum ATHANI - Pattin Sahakar Sangh Ainapur 15 Ainapur Vividha Uddeshagal - - Belgaum ATHANI - Sahakar Sangha Ltd., Ainapur 16 Ajayachetan Vividha - - Belgaum ATHANI - Uddeshagala S.S.Ltd., Athani 17 Akkamahadevi Vividha - - Belgaum ATHANI - Uddeshagala S.S.Ltd., Halalli 18 Akkamahadevi WOMEN Co-Op - - Belgaum ATHANI - Credit Society Ltd., Athani 19 Akkamamhadevi Mahila Pattin - - Belgaum -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. SRI. BASAVARAJ I ADDL

Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. SRI. BASAVARAJ I ADDL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 18-09-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 1 M.A. 8/2020 Moulasab Maktumsab Sangolli A.D. (HEARING) Age 70Yrs R/o Bailhongal Dist SHILLEDAR IA/1/2020 Belagavi. Vs The Chief officer Bailhongal Town Municipal Council Tq Bailhongal Dist Belagavi. 2 L.A.C. 607/2018 Laxman Dundappa Umarani age C B Padnad (EVIDENCE) 65 Yrs R/o Kesaral Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 3 L.A.C. 608/2018 Babalal Muktumasab Biradar C B Padanad (EVIDENCE) Patil Age 55 yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi. Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani, Tq Athani Dist Belagavi. 4 L.A.C. 609/2018 Gadigeppa Siddappa Chili age C B padanad (EVIDENCE) 65 Yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 5 L.A.C. 610/2018 Kedari Ningappa Gadyal age 45 C B Padanad (EVIDENCE) Yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 6 L.A.C. 611/2018 Smt Kallawwa alias Kedu Bhima C B padanad (EVIDENCE) Pujari Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani Dist Belagavi. 7 L.A.C. 612/2018 Kadappa Bhimappa Shirahatti C B Padanad (EVIDENCE) age 55 Yrs R/o Athani Tq Athani Dt Belagavi Vs The SLAO Hipparagi Project , Athani. Dist Belagavi. 1/8 Prl. District and Session Judge, Belagavi. SRI. BASAVARAJ I ADDL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE BELAGAVI Cause List Date: 18-09-2020 Sr. -

Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 5, Ver. V (May. 2015), PP 06-27 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Scheduling of Tribes: Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved V.S.Ramamurthy1 M.D.Narayanamurthy2 and S.Narayan3 1,2,3(No 422, 9th A main, Kalyananagar, Bangalore - 560043, Karnataka, India) Abstract: The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state has been done in 1950 by evolving a list of names of communities from a combination of the 1901 Census list of Animist-Forest and Hill tribes and V.R.Thyagaraja Aiyar's Ethnographic glossary. However, the pooling of communites as Animist-Forest & Hill tribes in the Census had occurred due to the rather artificial classification of castes based on whether they were not the sub- caste of a main caste, their occupation, place of residence and the fictitious religion called ‘Animists’. It is not a true reflection of the so called tribal characteristics such as exclusion of these communities from the mainstrream habitation or rituals. Thus Lambáni, Hasalaru, Koracha, Maleru (Máleru ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁‘sic’ Maaleru) etc have been categorized as forest and hill tribes solely due to the fact that they neither belonged to established castes such as Brahmins, Vokkaligas, Holayas etc nor to the occupation groups such as weavers, potters etc. The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state in the year 1950 was done by en-masse inclusion of some of those communities in the ST list rather than by the study of individual communities. -

1 John Stuart Mill on the Gender Pay Gap Virginie Gouverneur

John Stuart Mill on the gender pay gap Virginie Gouverneur – Preliminary draft - 0. Introduction Few detailed analyses of John Stuart Mill’s approach to gender wage inequality have been proposed. Yet, such an analysis seems to us essential from two points of view. First, elements of Mill’s study still seem relevant today and can enrich contemporary studies that focus on gender pay inequalities. In general, in modern approaches, the effect of social norms and custom on women’s wages is rarely considered as a full-fledged factor. In Mill’s analysis, the weight of custom, usage, and social norms (including that of the male-breadwinner), appear as essential causes of gender wage differences. Of course, the times are not the same and since the inequalities of wages between men and women have largely diminished. But old customs and norms, which have long prevailed in society, still persist today and continue to explain at least a part of the current wage differences between the sexes. It is therefore necessary to question the impact that they may have had at a given moment and that may have led to the persistence of their effects over time. Second, the approach developed by Mill is particularly interesting from the perspective of the history of ideas: on the question of women’s wages, Mill appears as a real exception among his peers economists. In general, contemporary commentators recognize as a remarkable fact that Mill has taken an interest in the problem of women’s low wages in his time. However, many of them expressed serious reservations about the scope of his analysis. -

3 B a Lanre-Abass and M Oguh-Xenophobia and Its

Vol. 5 No. 1 January – June, 2016 XENOPHOBIA AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL ORDER IN AFRICA DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ft.v5i1.3 Bolatito A. LANRE-ABASS, Ph.D and Matthew E. OGUH, MA Department of Philosophy, University of Ibadan Abstract Xenophobia, a form of discrimination practiced in countries, particularly in South Africa, is one of the major challenges confronting the modern day society. This paper examines xenophobia as a menace showing at the same time that this discriminatory practice bifurcates societies by creating a dichotomy amidst the various occupants of the society, thereby giving room for “otherness” rather than “orderliness”. The paper also highlights the philosophical implications of this societal bifurcation, particularly to the human community. Seeking a plausible way of addressing this challenge, the paper concludes by emphasizing the relevance of the value of tolerance in curbing xenophobia. Keywords : Xenophobia, Social discrimination, Tolerance, order and other, Africa. Introduction A basic plague that befalls some contemporary African societies is the monster called Xenophobia, which has as its features, discrimination and segregation and killing of non- members. As a result of this practice, any affected human society attempt to cut off setting portion of occupants for preserving them as the “other”. Thus, “otherness” rather than orderliness becomes a factor in some societies today. Most disheartening is the fact that it now seems immaterial whether these societies belong to the developed or third world countries as could be seen in the case of countries such as South African and Greece. In some African societies however, there abound fragments of the act of discrimination in almost all human societies within Africa, even though the gravity of its perpetuation varies from one country to another (MCKINLEY, ROBBINSON, and SOMAVIA 2001, 2-4). -

Growing Crimes Against Dalits in India Despite Special Laws: Relevance of Ambedkar’S Demand for ‘Separate Settlement’

Journal of Law and Conflict Resolution Vol. 3(9), pp. 151-168, November 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JLCR DOI: 10.5897/JLCR10.033 ISSN 2006-9804©2011 Academic Journals Review Growing crimes against Dalits in India despite special laws: Relevance of Ambedkar’s demand for ‘separate settlement’ A. Ramaiah Centre for study of social exclusion and inclusive policy, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 8 November, 2011 One of the major steps the independent India took in protecting the rights and dignity of Dalits was the enactment of special laws. Despite over sixty years of implementation of such laws and many developmental measures, atrocities against Dalits continue unabated. Quoting extensively from the government data on crimes against Dalits, this article logically argues the relevance of ‘separate settlement’ for Dalits proposed by none other than the architect of Indian Constitution Dr. B. R. Ambedkar to end caste based injustice and violence against Dalits. Key words: Hinduism, Caste, Dalits, human rights, untouchability, law, Constitution of India, separate settlement. INTRODUCTION With the proclamation of India as a sovereign secular interest, this article justifies the relevance of ―separate socialist democracy committed to secure all its citizens settlement', an option suggested and demanded by non liberty, equality and fraternity, it became an unequivocal other than the architect of the Indian Constitution Dr. B.R. necessity for the nation to protect -

CHAPTER 37 CRIME STATISTICS 37.1 Crime Statistics Is an Important and Essential Input for Assessing Quality of Life and the Human Rights Situation in the Society

CHAPTER 37 CRIME STATISTICS 37.1 Crime Statistics is an important and essential input for assessing quality of life and the human rights situation in the society. Crime Statistics broadly reflects the status of operations of Criminal Justice System in a Country. Crime Statistics includes data on Offences - Breaches of the law Offenders - Those who commit offences Victims - Those who are offended against In India Crime statistics are generated on the basis of crime records maintained by different law enforcing agencies like the Police, the Judiciary at different level of administrative/legal jurisdiction under the federative system of India. These statistics are normally readily available and are generally used for assessing how crime is being dealt with by law enforcement organisations, However, these statistics being based on those cases which are generally reported to the law enforcement agencies and recorded through all stages of action on the cases reported. 'Crime Statistics' in India gives an incomplete picture of crime situations in the country. The deficiency is not particular to India, as some studies have shown that even data collected by British Crime Statistics provides a picture of 30% of the actual crime in the country. 37.2 Source of Crime Statistics : 37.2.1 National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) is the nodal agency at the centre to collect, compile and disseminate the information related with crime. “Crime in India”, an annual compilation of NCRB, is being published since 1953. For this publication, the information in 22 standardized formats is being collected from all the 35 States/UTs as well as from 35 mega cities. -

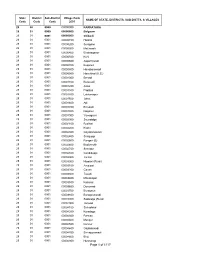

Village Code NAME of STATE, DISTRICTS, SUB-DISTTS

State District Sub-District Village Code NAME OF STATE, DISTRICTS, SUB-DISTTS. & VILLAGES Code Code Code 2001 29 00 0000 00000000 KARNATAKA 29 01 0000 00000000 Belgaum 29 01 0001 00000000 Chikodi 29 01 0001 00000100 Hadnal 29 01 0001 00000200 Sulagaon 29 01 0001 00000300 Mattiwade 29 01 0001 00000400 Bhatnaganur 29 01 0001 00000500 Kurli 29 01 0001 00000600 Appachiwadi 29 01 0001 00000700 Koganoli 29 01 0001 00000800 Hanabarawadi 29 01 0001 00000900 Hanchinal (K.S.) 29 01 0001 00001000 Benadi 29 01 0001 00001100 Bolewadi 29 01 0001 00001200 Akkol 29 01 0001 00001300 Padlihal 29 01 0001 00001400 Lakhanapur 29 01 0001 00001500 Jatrat 29 01 0001 00001600 Adi 29 01 0001 00001700 Bhivashi 29 01 0001 00001800 Naganur 29 01 0001 00001900 Yamagarni 29 01 0001 00002000 Soundalga 29 01 0001 00002100 Budihal 29 01 0001 00002200 Kodni 29 01 0001 00002300 Gayakanawadi 29 01 0001 00002400 Shirguppi 29 01 0001 00002500 Pangeri (B) 29 01 0001 00002600 Budulmukh 29 01 0001 00002700 Shendur 29 01 0001 00002800 Gondikuppi 29 01 0001 00002900 Yarnal 29 01 0001 00003000 Nippani (Rural) 29 01 0001 00003100 Amalzari 29 01 0001 00003200 Gavan 29 01 0001 00003300 Tavadi 29 01 0001 00003400 Manakapur 29 01 0001 00003500 Kasanal 29 01 0001 00003600 Donewadi 29 01 0001 00003700 Boragaon 29 01 0001 00003800 Boragaonwadi 29 01 0001 00003900 Sadalaga (Rural) 29 01 0001 00004000 Janwad 29 01 0001 00004100 Shiradwad 29 01 0001 00004200 Karadaga 29 01 0001 00004300 Barwad 29 01 0001 00004400 Mangur 29 01 0001 00004500 Kunnur 29 01 0001 00004600 Gajabarwadi 29 01 0001 00004700 Shivapurawadi 29 01 0001 00004800 Bhoj 29 01 0001 00004900 Hunnaragi Page 1 of 1117 State District Sub-District Village Code NAME OF STATE, DISTRICTS, SUB-DISTTS. -

Alternative Report

Alternative Report On the implementation Optional Protocol to the CRC on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography in INDIA Report prepared and submitted by: ECPAT International In collaboration with SANLAAP July 2013 1 Background information ECPAT International (End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes) is the leading global network working to end the commercial sexual exploitation of children (child prostitution, child pornography, child trafficking and child sex tourism). It represents 81 member organisations from 74 countries. ECPAT International holds Consultative status with ECOSOC. Website: www.ecpat.net SANLAAP literally means “dialogue” work to end child prostitution, trafficking and sexual abuse of children. Sanlaap collaborates with different stakeholders, both governmental and non- governmental to end trafficking and punish traffickers. SANLAAP operates from Kolkata and Delhi but networks with civil society organisations, police and governments all over India. Website: http://www.sanlaapindia.org/ 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction p.4 2. General measures of implementation p.5 3. Prevention of commercial sexual exploitation of children p.6 4. Prohibition of the manifestations of commercial sexual exploitation p.10 of children 5. Protection of the rights of child victims p.13 3 1. Introduction Despite a lack of research and data on the scale of commercial sexual exploitation of children in India, estimates show that many children are victims of sexual violence. UNICEF estimates that 1.2 million children are victims of prostitution in India1. The government of India has recently made significant progress in the development of laws and policies to address the different manifestations of commercial sexual exploitation of children, including the adoption in April 2013 of the National Policy for Children, which contains specific measures to prevent and combat commercial sexual exploitation of children. -

Joint Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Adoption of List of Issues

JOINT SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, ADOPTION OF LIST OF ISSUES 126TH SESSION, (01 to 26 July 2019) JOINTLY SUBMITTED BY NATIONAL DALIT MOVEMENT FOR JUSTICE-NDMJ (NCDHR) AND INTERNATIONAL DALIT SOLIDARITY NETWORK-IDSN STATE PARTY: INDIA Introduction: National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ)-NCDHR1 & International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) provide the below information to the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee (the Committee) ahead of the adoption of the list of issues for the 126th session for the state party - INDIA. This submission sets out some of key concerns about violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the Covenant) vis-à- vis the Constitution of India with regard to one of the most vulnerable communities i.e, Dalit's and Adivasis, officially termed as “Scheduled Castes” and “Scheduled Tribes”2. Prohibition of Traffic in Human Beings and Forced Labour: Article 8(3) ICCPR Multiple studies have found that Dalits in India have a significantly increased risk of ending in modern slavery including in forced and bonded labour and child labour. In Tamil Nadu, the majority of the textile and garment workforce is women and children. Almost 60% of the Sumangali workers3 belong to the so- called ‘Scheduled Castes’. Among them, women workers are about 65% mostly unskilled workers.4 There are 1 National Dalit Movement for Justice-NCDHR having its presence in 22 states of India is committed to the elimination of discrimination based on work and descent (caste) and work towards protection and promotion of human rights of Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) across India.