Mother-Goddess Author(S): Andrew Fleming Source: World Archaeology, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Étude Sur Quelques Éléments Figuratifs Des Statues-Menhirs Et Stèles Européennes Du Néolithique À L'age Du Bronze

Étude sur quelques éléments figuratifs des statues-menhirs et stèles européennes du Néolithique à l'Age du Bronze Lhonneux Tatiana Master en histoire de l'art et archéologie Orientation générale – Option générale – Finalité approfondie Directeur : Pierre Noiret Lecteurs : Marcel Otte – Nicolas Cauwe Volume I Université de Liège – Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Année académique 2018-2019 Remerciements Ce mémoire est l’aboutissement d’un long parcours que je n’aurais pas pu réaliser seule. Aussi je tiens à remercier chaleureusement toutes les personnes qui, de près ou de loin, ont contribué à l’accomplissement de ce cheminement. Au terme de ce travail, je tiens à exprimer ma profonde gratitude à Monsieur Noiret qui, en tant que Directeur de mémoire, s’est toujours montré à l’écoute et disponible. Je le remercie pour l’aide et le temps qu’il a bien voulu me consacrer et sans qui ce mémoire n’aurait jamais vu le jour. Je voudrais saisir cette occasion pour témoigner toute ma reconnaissance à Monsieur Otte, pour ses précieux conseils dans mes recherches et questionnements. Je le remercie également pour le prêt de l'ouvrage sur les stèles provençales ; ouvrage faisant partie de sa collection personnelle. Dans cette même lancée, je remercie également Monsieur Cauwe d'avoir su me rediriger sur la bonne voie dans l'élaboration de mon travail et d'avoir su me remotiver pour le finaliser. Je tiens à exprimer ma gratitude aux quelques musées, qui m'ont aimablement répondu sur la localisation de certaines statues-menhirs et stèles, ainsi que m’avoir fourni quelques références bibliographiques fort utiles. -

Bibliography Updated 2016

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Select Bibliography Northwest Wales 2016 Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age Select Bibliography Northwest Wales - Neolithic Baynes, E. N., 1909, The Excavation of Lligwy Cromlech, in the County of Anglesey, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. IX, Pt.2, 217-231 Bowen, E.G. and Gresham, C.A. 1967. History of Merioneth, Vol. 1, Merioneth Historical and Record Society, Dolgellau, 17-19 Burrow, S., 2010. ‘Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey: alignment, construction, date and ritual’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, Vol. 76, 249-70 Burrow, S., 2011. ‘The Mynydd Rhiw quarry site: Recent work and its implications’, in Davis, V. & Edmonds, M. 2011, Stone Axe Studies III, 247-260 Caseldine, A., Roberts, J.G. and Smith, G., 2007. Prehistoric funerary and ritual monuments survey 2006-7: Burial, ceremony and settlement near the Graig Lwyd axe factory; palaeo-environmental study at Waun Llanfair, Llanfairfechan, Conwy. Unpublished GAT report no. 662 Davidson, A., Jones, M., Kenney, J., Rees, C., and Roberts, J., 2010. Gwalchmai Booster to Bodffordd link water main and Llangefni to Penmynydd replacement main: Archaeological Mitigation Report. Unpublished GAT report no 885 Hemp, W. J., 1927, The Capel Garmon Chambered Long Cairn, Archaeologia Cambrensis Vol. 82, 1-43, series 7 Hemp, W. J., 1931, ‘The Chambered Cairn of Bryn Celli Ddu’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 216-258 Hemp, W. J., 1935, ‘The Chambered Cairn Known As Bryn yr Hen Bobl near Plas Newydd, Anglesey’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. 85, 253-292 Houlder, C. H., 1961. The Excavation of a Neolithic Stone Implement Factory on Mynydd Rhiw, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 27, 108-43 Kenney, J., 2008a. -

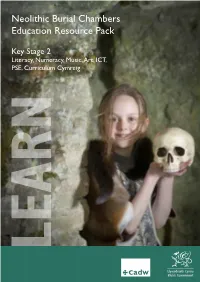

Neolithic Resource

Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource Pack Key Stage 2 Literacy, Numeracy, Music, Art, ICT, PSE, Curriculum Cymreig LEARN Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource Neolithic burial chambers in Cadw’s care: Curriculum links: Barclodiad-y-Gawres passage tomb, Anglesey Literacy — oracy, developing & presenting Bodowyr burial chamber, Anglesey information & ideas Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey Numeracy — measuring and data skills Capel Garmon burial chamber, Conwy Music — composing, performing Carreg Coetan Arthur burial chamber, Pembrokeshire Din Dryfol burial chamber, Anglesey Art — skills & range Duffryn Ardudwy burial chamber, Gwynedd Information Communication Technology — Lligwy burial chamber, Anglesey find and analyse information; create & Parc le Breos chambered tomb, Gower communicate information Pentre Ifan burial chamber, Pembrokeshire Personal Social Education — moral & spiritual Presaddfed burial chamber, Anglesey development St Lythans burial chamber, Vale of Glamorgan Curriculum Cymreig — visiting historical Tinkinswood burial chamber, Vale of Glamorgan sites, using artefacts, making comparisons Trefignath burial chamber, Anglesey between past and present, and developing Ty Newydd burial chamber, Anglesey an understanding of how these have changed over time All the Neolithic burial chambers in Cadw’s care are open sites, and visits do not need to be booked in advance. We would recommend that teachers undertake a planning visit prior to taking groups to a burial chamber, as parking and access are not always straightforward. Young people re-creating their own Neolithic ritual at Tinkinswood chambered tomb, Vale of Glamorgan, South Wales cadw.gov.wales/learning 2 Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource The Neolithic period • In west Wales, portal dolmens and cromlechs The Neolithic period is a time when farming was dominate, which have large stone chambers possibly introduced and when people learned how to grow covered by earth or stone mounds. -

Étude Sur Quelques Éléments Figuratifs Des Statues-Menhirs Et Stèles Européennes Du Néolithique À L'age Du Bronze

Étude sur quelques éléments figuratifs des statues-menhirs et stèles européennes du Néolithique à l'Age du Bronze Lhonneux Tatiana Master en histoire de l'art et archéologie Orientation générale – Option générale – Finalité approfondie Directeur : Pierre Noiret Lecteurs : Marcel Otte – Nicolas Cauwe Volume II Université de Liège – Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Année académique 2018-2019 Introduction Ce catalogue rassemble 217 statues-menhirs et stèles européennes, reprises dans un recueil d'illustrations. J'ai tenté de diversifier les types de documents par des photographies en noir et blanc, en couleur et par des dessins. Il faut préciser toutefois que certains clichés présentent une qualité médiocre, faute d'avoir mieux à proposer. Certaines périodes, plus anciennes, posent plus de problématiques que d’autres, c’est la raison pour laquelle j’ai décidé de me concentrer sur elles : il s’agit du Néolithique, du Chalcolithique ainsi que de l’Age du Bronze. La datation des monuments peut varier au cours de mon analyse. Je me suis basée, en effet, sur les chronologies les plus fréquentes afin de placer les monuments dans une période donnée. Pour s'entendre sur les termes utilisés, vous trouverez, ci-dessous, une définition de chaque type de sculptures : – statue-menhir : L'expression « statue-menhir » a été créée par l'abbé Hermet1: c'est d'abord une statue, sous la forme d'une pierre épaisse ovale, ogivale ou rectangulaire2, s'efforçant à représenter un corps humain par son bas-relief et une silhouette humaine par sa mise en forme. Sa réalisation peut être grossière ou stylisée. C'est, ensuite, une sculpture qui se dresse comme un menhir3 (terme apparu pour la première fois sous la plume de l'abbé Hermet en 1891) fichée en terre. -

Nash & Stanford, (Nash & Stanford 2007)

ciblées sont nécessaires. En ce qui concerne le tourisme well-directed action is needed. Concerning tourism and et la méthodologie de la recherche, l’Université de Gand research methodology, Ghent University will examine examinera les possibilités de méthodes simples et ren- the possibilities of simple and cost-effective methods tables adaptées aux besoins des populations locales. adapted to the needs of the indigenous population. Remerciements !CKNOWLEDGMENTS Les auteurs tiennent à remercier le soutien financier apporté par The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support provi- l’IWT et FWO-Flandres, qui nous ont aidés à organiser nos expéditions ded by IWT and FWO-Flanders, which helped us to organize our expe- et la recherche en laboratoire. Nous tenons également à remercier l’Uni- ditions and the desk-based research. We also wish to thank the Gorno versité d’État Gorno Altaisk pour le travail de terrain commun. Altaisk State University for the joint fieldwork. Gertjan PLETS1, Wouter GHEYLE2 & Jean BOURGEOIS3 1 Department of Archaeology, University Ghent – [email protected] 2 Department of Archaeology, University Ghent – [email protected] 3 Head of the Department of Archaeology, University Ghent – [email protected] BIBLIOGRAPHIE BOURGEOIS I., HOOF L.V., CHEREMISIN D., 1999. — Découverte de pétroglyphes dans les vallées de Sebystei et de Kalanegir (Gorno-Altai). INORA, 22, p. 6-13. CASSEN S., ROBIN G., 2010. — Recording Art on Neolithic Stelae and Passage Tombs from Digital Photographs. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 17, p. 14. CHANDLER J.H., BRYAN P., FRYER J.G., 2007. — The Development and Application of a Simple Methodology for Recording Rock Art Using Consumer-Grade Digital Cameras. -

Anglesey Historical Sites

Anglesey Historical Sites Anglesey Historical Sites Postcodes are for sat-nav purposes only and may not represent the actual address of the site What Where Post Code Description Barclodiad y Gawres A Neolithic burial chamber, it is an example of a cruciform passage grave, a notable Between Rhosneigr and Aberffraw LL63 5TE Burial Chamber feature being its decorated stones. Beaumaris was the last of Edward I’s “iron ring” of castles along the North Wales Beaumaris Castle Beaumaris LL58 8AP coast. Technically perfect and constructed to an ingenious “walls within walls” plan. One of Wales’ most important megalithic sites, this passage mound encompasses a single white pillar inside and, along with a few other select sites in Europe, Bryn Celli Ddu Llanddaniel Fab LL61 6EQ is believed to have been constructed with the ability to measure the year constructed into its design. The passage is orientated towards the rising summer solstice sun. This is Wales’ equivalent to Stonehenge. This small fortlet is one of Europe’s only three-walled Roman forts. The fourth side fronted the sea and was probably the site of a quay. Its date is unknown, but it is Caer Gybi Holyhead LL65 3AD generally thought to be part of a late 4th century scheme, associated with Segontium, which was set up to defend the west coast against Irish sea-raiders. Castell Bryngwyn Brynsiencyn LL61 6TZ Neolithic, Iron Age, ancient druid, Roman ancient Anglesey site Neolithic chambered tomb. The burial mound developed over several phases, LL62 5DD Din Dryfol Bethel culminating in a 3m high portal stone creating a substantial entrance. -

Revealing Guernsey's Ancient History in Fact and Fiction

REVEALING GUERNSEY’S ANCIENT HISTORY IN FACT AND FICTION [Received January 25th 2016; accepted June 22nd 2016 – DOI: 10.21463/shima.10.2.12] Peter Goodall University of Southern Queensland <[email protected]> ABSTRACT: In G. B. Edwards’ novel of 20th Century Guernsey life, The Book of Ebenezer Le Page (1981), Ebenezer becomes the unlikely custodian of an ‘ancient monument’ discovered on his land. The incident is treated, in the main, as a topic for comedy—a part of the novel’s satire of the many pretences and frauds of modern Guernsey—but the underlying issues should not be lightly put aside. ‘Les Fouaillages’, a megalithic site discovered in 1978, the year after Edwards’s death, on L’Ancresse Common, a short walk from the place where the fictional Ebenezer spent his whole life, is thought to be 6000 years old, and has a claim to be amongst the oldest built sites on the planet. There are many other ancient sites and monuments on this small island, as there are on the neighbouring Channel Island of Jersey. This article looks at the interconnected yet contrasting ways in which this extraordinary legacy on Guernsey has been revealed and described: the scholarly discourse of archaeology, the myth and legend of the popular imagination, and the literature of Guernsey’s poets and novelists. KEYWORDS: Guernsey; Neolithic Age; megaliths; G. B. Edwards; Victor Hugo. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - All over Europe, especially western Europe, can be found the remains of what we now call ‘Neolithic’, or New Stone Age, culture, a period that in European history stretched from (roughly) 7000 BC to (roughly) 2000 BC, depending upon location. -

Stone Portals by Sergey Smelyakov [email protected]

The Stone Portals by Sergey Smelyakov [email protected] This issue starts hosting of English edition of the e-book The Stone Portals (http://www.astrotheos.com/EPage_Portal_HOME.htm). The first Chapter presents the classification and general description of the stone artefacts which are considered the stone portals: stone – for their substance, and portals – for their occult destination. Their main classes are the pyramids, cromlechs, and stone mounds, as well as lesser forms – stone labyrinths et al. Then, chapter by chapter, we analyze the classes of these artefacts from the viewpoint of their occult and analytical properties, which, as it turned out, in different regions of the world manifest the similar properties in astronomical alignments, metrological and geometrical features, calendaric application, and occult destination. The second Chapter deals with the first, most extensive class of the Stone Portals – the Labyrinth- Temples presented by edifices of various types: Pyramids, mounds, etc. This study is preceded by an overview of astronomic and calendaric concepts that are used in the subsequent analysis. The religious and occult properties are analyzed relative to the main classes of the Labyrinth-Temples disposed in Mesoamerica and Eurasia, but from analytical point of view the main attention is devoted to Mesoamerican pyramids and European Passage Mounds. Thus a series of important properties are revealed re to their geometry, geodesy, astronomy, and metrology which show that their builders possessed extensive knowledge in all these areas. At this, it is shown that although these artefacts differ in their appearance, they have much in common in their design detail, religious and occult destination, and analytic properties, and on the world-wide scale. -

Proprietà Tecnologiche E Provenienza Delle Materie Prime

The Journal of Fasti Online (ISSN 1828-3179) ● Published by the Associazione Internazionale di Archeologia Classica ● Palazzo Altemps, Via Sant'Appolinare 8 – 00186 Roma ● Tel. / Fax: ++39.06.67.98.798 ● http://www.aiac.org; http://www.fastionline.org Proprietà tecnologiche e provenienza delle materie prime impiegate per la produzione delle statue menhir di Aiodda-Nurallao (Sardegna centrale): il contributo dell’archeometria Marco Serra – Valentina Mameli – Carla Cannas Macroscopic examinations and chemical measurements by non destructive pXRF, ICP-OES and ICP-MS have been ap- plied on 10 geological samples collected from the fossiliferous limestone of the Villagreca Unit, outcropping in Nurallao (central Sardinia). The results of this study have allowed to determine the geochemical intra-source variability of the lithic raw material while the mineralogical investigation performed by PXRD on the same geological samples have led to define some technological properties of the limestone. Then, on 13 Eneolithic menhirs coming from the archaeological site of Aiodda-Nurallao (dating back to the 3rd millennium BC) non destructive pXRF measurements and visual observations have been carried out according to conservative limitations. Through the comparison between artifacts and lithological outcrop’s analytical data, the authors have been able to define the geological source of the raw materials employed in megalithic sculptures manufacturing. Basing on the raw material technological properties, it has been possible to record the trend to select soft stones easy to work by prehistoric technologies. Introduzione Negli anni ’70 del XX secolo la sepoltura dell’età del Bronzo sita nella località rurale di Aiodda, in agro di Nurallao (CA) (figg. -

Carreglwyd Coastal Cottages Local Guide

Carreglwyd Coastal Cottages Local Guide This guide has been prepared to assist you in discovering the host of activities, events and attractions to be enjoyed within a 20 mile radius (approx) of Llanfaethlu, Anglesey Nearby Holiday Activities Adventure Activities Holyhead on Holy Island More Book a day trip to Dublin in Ireland. Travel in style on the Stena HSS fast craft. Telephone 08705707070 Info Adventure Sports Porth y Felin, Holyhead More Anglesey Adventures Mountain Scrambling Adventure and climbing skill courses. Telephone 01407761777 Info Holyhead between Trearddur Bay and Holyhead More Anglesey Outdoors Adventure & Activity Centre A centre offering educational and adventure activities. Telephone 01407769351 Info Moelfre between Amlwch and Benllech More Rock and Sea Adventures The company is managed by Olly Sanders a highly experienced and respected expedition explorer. Telephone 01248 410877 Info Ancient, Historic & Heritage Llanddeusant More Llynnon Mill The only working windmill In Wales. Telephone 01407730797 Info Church Bay More Swtan Folk Museum The last thatched cottage on Anglesey. Telephone 01407730501 Info Lying off the North West coast of Anglesey More The Skerries Lighthouse The lighthouse was established in 1717 Info Llanfairpwll between Menai Bridge and Brynsiencyn More The Marques of Anglesey's Column A column erected to commemorate the life of Henry William Paget Earl of Uxbridge and 1st Marques of Anglesey. Info Llanfairpwll between Menai Bridge and Pentre-Berw More Lord Nelson Monument A memorial to Lord Nelson erected in 1873 sculpted by Clarence Paget. Info Amlwch between Burwen and Penysarn More Amlwch Heritage Museum The old sail loft at Amlwch has been developed as a heritage museum. -

THE CLAVA CAIRNS1 by IAI

THE CLAVA CAIRNS1 by IAI . NWALKERC , M.A., F.S.A.SCOT. THIS pape divides ri d into three parts discussio:a generae th f no l affinities, sucs ha they are, of the Clava cairns; a discussion of their geographical setting; and some remark thein so r possible dating.2 n discussinI g possible affinitie cairnse immediatels i th e f o son , y e structh y kb uniqueness of the group as a whole compared with other groups of megalithic tombs. There are five outstanding features: firstly, the dual element of ring-cairn and passage-grave in a group which seems otherwise completely indivisible; secondly, the us f corbellineo r roofingfo e passage-graveth g s (and paralle thiso t le equall th , y distinctive open chambered non-passaged construction of the ring-cairn); thirdly, surroundine th g circl free-standinf eo g stones; fourthly orientatioe th , f passageno - grav ring-caird ean n alike toward . quarter Se W sth fifthlyd an presenc;e th ,p cu f eo marks both on stones forming part of the cairn and on boulders in the general area of Clava cairn distribution. The nearest parallels to the ring-cairns are in the superficially analagous struc- ture Almerin si southern ai n Spain,3 though Blance4 believes that som thesf eo e latter were used as ossuaries rather than places for collective burial. Passage-graves in general can be shown to have an Atlantic-Irish Sea distribution, from Iberia north- wards,5 though the Irish Sea area is certainly equally an area of gallery-grave distribution. -

Book Chapter Reference

Book Chapter Rawk: Statues-Menhirs and Anthropomorphic Statues of Ancient Wadi ‘Idim STEIMER, Tara Abstract Summary: “The rugged highlands of southern Yemen are one of the less archaeologically explored regions of the Near East. This final report of survey and excavations by the Roots of Agriculture in Southern Arabia (RASA) Project addresses the development of food production and human landscapes, topics of enduring interest as scholarly conceptualizations of the Anthropocene take shape. Along with data from Manayzah, site of the earliest dated remains of clearly domesticated animals in Arabia, the volume also documents some of the earliest water management technologies in Arabia, thereby anchoring regional dates for the beginnings of pastoralism and of potential farming. The authors argue that the initial Holocene inhabitants of Wādī Sanā were Arabian hunters who adopted limited pastoral stock in small social groups, then expanded their social collectives through sacrifice and feasts in a sustained pastoral landscape. This volume will be of interest to a wide audience of archaeologists including not only those working in Arabia, but more broadly those interested in the ancient Near East, Africa, South Asia, and in [...] Reference STEIMER, Tara. Rawk: Statues-Menhirs and Anthropomorphic Statues of Ancient Wadi ‘Idim. In: Joy McCorriston, Mickael J. Harrower. Landscape History of Hadramawt: The Roots of Agriculture in Southern Arabia (RASA) Project 1998-2008. Los Angeles : Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2020. p. 455-474 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:140740 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Landscape History Landscape Landscape History of Hadramawt The Roots of Agriculture in Southern Arabia (RASA) Project 1998–2008 he rugged highlands of southern Yemen are one of the less archaeologically explored regions of Tthe Near East.