The Quint V2.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Du Fay Discography

Guillaume Du Fay Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) builds on the work published in Fanfare in January and March 1980. There are more than three times as many entries in the updated version. It has been published in recognition of the publication of Guillaume Du Fay, his Life and Works by Alejandro Enrique Planchart (Cambridge, 2018) and the forthcoming two-volume Du Fay’s Legacy in Chant across Five Centuries: Recollecting the Virgin Mary in Music in Northwest Europe by Barbara Haggh-Huglo, as well as the new Opera Omnia edited by Planchart (Santa Barbara, Marisol Press, 2008–14). Works are identified following Planchart’s Opera Omnia for the most part. Listings are alphabetical by title in parts III and IV; complete Masses are chronological and Mass movements are schematic. They are grouped as follows: I. Masses II. Mass Movements and Propers III. Other Sacred Works IV. Songs (Italian, French) Secular works are identified as rondeau (r), ballade (b) and virelai (v). Dubious or unauthentic works are italicised. The recordings of each work are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available; then the format of the recording (78, 45, LP, LP quad, MC, CD, SACD), the label, and the issue number(s). Each recorded performance is indicated, if known, as: with instruments, no instruments (n/i), or instrumental only. Album titles of mixed collections are added. ‘Se la face ay pale’ is divided into three groups, and the two transcriptions of the song in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch are arbitrarily designated ‘a’ and ‘b’. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

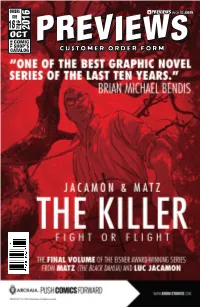

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 OCT 2016 OCT COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Oct16 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 9/8/2016 4:16:17 PM Oct16 Archie.indd 1 9/8/2016 9:50:56 AM THE LEGEND MOTOR CRUSH #1 OF ZELDA: IMAGE COMICS ART & ARTIFACTS HC DARK HORSE COMICS SUPERGIRL: BEING SUPER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT ALIEN VS. PREDATOR: ROCKSTARS #1 LIFE AND DEATH #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS LOCKE & KEY: SMALL WORLD ONE-SHOT IDW ENTERTAINMENT JUSTICE LEAGUE VS. U.S.AVENGERS #1 SUICIDE SQUAD #1 MARVEL COMICS DC ENTERTAINMENT Oct16 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 9/8/2016 4:10:22 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Rough Riders Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Reggie & Me #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber: Invasion #1 l AVATAR PRESS The Avengers: Steed & Mrs Peel: The Diana Magazine Stories Volume 1 GN l BIG FINISH PRODUCTIONS Jim Henson’s The Storyteller: Giants #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Klaus and the Witch of Winter One-Shot l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Wonder Woman ‘77 Meets the Bionic Woman 77 #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Red Sonja #0 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Another Castle: Grimoire TP l ONI PRESS Disney’s Great Parodies Volume 1: Mickey’s Inferno GN/HC l PAPERCUTZ Hookjaw #1 l TITAN COMICS World War X #1 l TITAN COMICS Divinity III: Stalinverse #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Tomie Complete Deluxe Editon HC l VIZ MEDIA The Pokemon Cookbook Sc l VIZ MEDIA BOOKS 2 Mercenary: The Freelance Illustration of Dan Brereton HC l ART BOOKS Krazy: The Black & White World of George Herriman HC l COMICS The Art of Archer HC l MOVIE/TV The Art of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story HC l STAR WARS Star Wars Little Golden Book: I Am a Stormtrooper l STAR WARS - YOUNG READERS MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who Magazine Special #45: 2017 Yearbook l DOCTOR WHO Birth.Movies.Death. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Open Letter Expresses Its Gratitude to the Ontario Arts Council OPEN LETTER Tenth Series, No

Open Letter expresses its gratitude to the Ontario Arts Council OPEN LETTER Tenth Series, No. 4, Fall 1998 which last year awarded $5,500 bpNichol + 10 in support of its publications Open Letter acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $7,100 in our organization Open Letter remercie de son soutien le Conseil des Arts du Canada qui lui a accordé $7,100 l’an denier Contents bpNichol + 10 FRANK DAVEY 5 Coach House Letters DAVID ROSENBERG 14 st. Ink BILLY LITTLE 23 Nicholongings: because they is LORI EMERSON 27 False Portrait of bpNichol as Charles Lamb STEVE MCCAFFERY 34 A correction to David Rosenberg’s article “Crossing the Border: A Coach Argument for a Secular Martyrology House Memoir” (Open Letter Series 9, No. 9): David Rosenberg writes, DARREN WERSHLER-HENRY 37 “Abstract Expressionism was the movement I alluded to in ‘Crossing the The bpNichol Archive at Simon Fraser University Border: A Coach House Memoir.’ That it became ‘Im’ in print is a GENE BRIDWELL 48 Freudian slip: I was perhaps overly impressed with my point.” Sounding out the Difference: Orality and Repetition in bpNichol SCOTT POUND 50 flutterings for bpNichol STEVEN SMITH 59 Nickel Linoleum CHRISTIAN BÖK 62 Extreme Positions ROBERT HOGG 75 An Interview with Steve McCaffery on the TRG PETER JAEGER 77 for bpNichol: these re-memberings DOUGLAS BARBOUR 97 Artifacts of Ecological Mind: bp, Gertrude, Alice DAVID ROSENBERG 109 bpNichol is alive and well and living in Bowmanville, ON STEPHEN CAIN 115 “Turn this Page”: Journaling bpNichol’s The Martyrology and the Returns ROY MIKI 116 Contributors 134 6 Open Letter 10:4 Wittgenstein. -

ABSTRACT the Pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group Warrant Serious Consideration As .A Legitimate Narrative Enterprise

DOCU§ENT RESUME ED 190 980 CS 005 088 AOTHOR Palumbo, Don'ald TITLE The use of, Comics as an Approach to Introducing the Techniques and Terms of Narrative to Novice Readers. PUB DATE Oct 79 NOTE 41p.: Paper' presented at the Annual Meeting of the Popular Culture Association in the South oth, Louisville, KY, October 18-20, 19791. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage." DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature:,*Comics (Publications) : *Critical Aeading: *English Instruction: Fiction: *Literary Criticism: *Literary Devices: *Narration: Secondary, Educition: Teaching Methods ABSTRACT The pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group warrant serious consIderation as .a legitimate narrative enterprise. While it is obvious. that these comic books can be used in the classroom as a source of reading material, it is tot so obvious that these comic books, with great economy, simplicity, and narrative density, can be used to further introduce novice readers to the techniques found in narrative and to the terms employed in the study and discussion of a narrative. The output of the Marvel Conics Group in particular is literate, is both narratively and pbSlosophically sophisticated, and is ethically and morally responsible. Some of the narrative tecbntques found in the stories, such as the Spider-Man episodes, include foreshadowing, a dramatic fiction narrator, flashback, irony, symbolism, metaphor, Biblical and historical allusions, and mythological allusions.4MKM1 4 4 *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ) U SOEPANTMENTO, HEALD.. TOUCATiONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF 4 EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT was BEEN N ENO°. DOCEO EXACTLY AS .ReCeIVED FROM Donald Palumbo THE PE aSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGuN- ATING T POINTS VIEW OR OPINIONS Department of English STATED 60 NOT NECESSARILY REPRf SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF O Northern Michigan University EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY CO Marquette, MI. -

Korean Students in New York City, 1907-1937 Jean H. Park Submitted

Exiled Envoys: Korean Students in New York City, 1907-1937 Jean H. Park Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Jean H. Park All Rights Reserved Abstract Exiled Envoys: Korean Students in New York City, 1907-1937 Jean H. Park This dissertation follows the activism of Korean students in New York City and the trajectory of their American education as it applied to Korea’s colonization under the Empire of Japan. As a focused historical account of the educational experiences of Korean students in New York from 1907 to 1937, this dissertation uses archival evidence from their associations, correspondence, publications, and the institutions they studied at to construct a transnational narrative that positions the Korean students operating within and outside the confines of their colonial experience. The following dissertation answers how the Korean students applied their American education and experiences to the Korean independence movement, and emphasizes the interplay of colonization, religion, and American universities in contouring the students’ activism and hopes for a liberated Korea. Table of Contents List of Charts, Graphs, Illustrations ................................................................................................ ii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iii Dedication -

Alongingly the Way”: Ontology and Longing in Bpnichol’S the Martyrology

“all alongingly the way”: Ontology and Longing in bpNichol’s The Martyrology A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in English University of Regina By Jeremy Michael Desjarlais Regina, Saskatchewan November, 2016 Copyright 2016: J.M. Desjarlais UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Jeremy Michael Desjarlais, candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in English, has presented a thesis titled, "all alongingly the way": Ontology and Longing in bpNichol's The Martyrology, in an oral examination held on November 23, 2016. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: Dr. Dennis Cooley, St. John’s College, University of Manitoba Supervisor: Dr. Christian Riegel, Deparmtnet of English Committee Member: Dr. Medrie Purdham, Deparmtnet of English Committee Member: Dr. Lynn Wells, First Nations University of Canada Chair of Defense: Dr. JoAnn Jaffe, Department of Sociology and Social Studies i Abstract bpNichol’s (1944-1988) long poem, The Martyrology (published between 1972 and, posthumously, 1993), is a work that is comprised of text, illustrations, and musical notations. Its sheer length, both in time of composition and page range, as well as its reach, in its thematic inclusion and incorporated written styles, constitute its demanding and comprehensive form. Critics have neglected to examine the poem as a work preoccupied with the philosophy of ontology—the study of being—through a literary mode of longing. -

EGE-Febmarch 06

East Gate Edition U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Far East District February/March 2006 Volume 16, Number 2 Engineers Day gives Seoul American High School students lessons to build on See Pages 6-7 Inside From the Commander POD commander receives first star . .3 Camp Humphreys relocation effort . .4 Well, we have had our first dose of yellow dust for the year. Not exactly the most cheerful first sign Engineers Day gives Seoul American High School students lessons . 6-7 of spring, as I would prefer to see forsythias and azaleas blooming, but a sign of spring all the same. I Strengthening the Alliance through Engineering . 8-9 am still waiting to see March change from a lion to a lamb but I’ll keep my fingers crossed since we have a The most needed - Facilities and Services couple of more weeks remaining in the month. Branch . 10-11 We have however, had projects begin to Iraq’s youngest citizens . .12-13 bloom in the relocation programs. We are no longer Still serving with pride . 14-15 “waiting” for the Minister of National Defense to Col. Janice L. Dombi purchase the land in Pyongtaek. All of the land is Corps couple celebrate silver anniversary in Iraq . .18 purchased, and in the final week of February, the Minister of National Defense signed the first parcel of land over to USFK. This is the land we need to con- Around the Corps . .20-21 struct the 2007 Military Construction program facilities. These new barracks and dining facility are sited in a location that works well in the master plan that the On the cover U.S. -

Fuckan Theory and Bill Bissett's Concrete Poetics

Darren Wershler-Henry / VERTICAL EXCESS: what fuckan theory and bill bissett's Concrete Poetics When considering the subject of bill bissett's concrete poetry, the first problem that arises is a major one, with both pragmatic and philo sophic components. Where does the "concrete" begin, where does it end, and can it be isolated and described? bissett, a figure the late Warren Tallman was fond of describing as "a one man civilization" (106), has produced a nearly constant flow of art over the last thirty odd years, and continues to do so without any signs of abating. Much of this staggeringly large body of work is highly visual in nature, and all of it defies conventional notions of genre: collages are paintings and drawings bleed into poems turn into scores for reading and chant and performance generates writing bound into books published sometimes or not. In "bill bissett: A Writing Outside Writing," Steve McCaffrey eloquently delineates the dilemma that the critic faces. In order to address the excessive nature of the libidinal flow that consti tutes bissett's art without reducing it to a kind of thematics, "it is not possible to actually read Bissett [sic]. What must be adopted is a comprehensive overview, a reading beyond a reading to affirm the intensity of desire" (102). In other words, critical analyses of bissett's glyphic violations of grammar as ruptures "inside" the restricted economy of writing will inevitably repeat that economy's strategies to repress the gestures of the poems towards an impossible (but neces sary) Utopian "outside." How, then, can a reader or critic proceed? Fredric Jameson writes in Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism that since imagining Utopia is an impossible act by definition, "It is thus the limits, the systemic restrictions and repressions, or empty places, in the Utopian blueprint that are the most interesting, for these alone testify to the ways a culture or system marks the most visionary mind and 117 contains its movement toward transcendence" (208). -

Intermixx Webzine Online Edition

by Noel Ramos I recently interviewed the lovely Quinn Lemley, a rather unique InterMixx mem- ber in that she performs a hybrid of jazz, cabaret and lounge music. INTERMIXX: Quinn, I am very pleased that you have joined InterMixx and are in- volved in our activities. Do you consider yourself an "indie" artist, and if so, how do you define indie? QUINN: Yes Noel, I am definitely an "Indie," so much of the jazz/cabaret/lounge community is these days with labels pulling back their support in our genre. The great thing about being an "Indie" is that I had the opportunity to create my own vision for each of my recordings. INTERMIXX: In your opinion, what are the main problems concerning indie musicians at this time? QUINN: Financing and Distribution. We are "the engine" for everything. INTERMIXX: Your style of music is still somewhat unique amongst our membership, and I commend you on your DIY attitude. Can you describe what you do for our readers? QUINN: Of course, I am a hybrid of lounge/jazz and caba- ret. Some of my music is a big band feel and others a small four piece combo, it's sultry, sexy, fun music. Sort of a cross between Keeley Smith, Ann-Margret and Julie London. INTERMIXX: Tell us more about your portrayal of Rita Hayworth, and how that came to happen. Was it largely because of your resemblance to the beauty queen? QUINN: You are a doll, yes, I was doing a musical off Broadway and a friend of mine, Preston Ridge saw it, and he said that I should do a musical about the life and music of Rita Hayworth because I resembled her. -

The Writings of Henry Cu

P~per No. 13 The Writings of Henry Cu Kim The Center for Korean Studies was established in 1972 to coordinate and develop the resources for the study of Korea at the University of Hawaii. Its goals are to enhance the quality and performance of Uni versity faculty with interests in Korean studies; develop compre hensive and balanced academic programs relating to Korea; stimulate research and pub lications on Korea; and coordinate the resources of the University with those of the Hawaii community and other institutions, organizations, and individual scholars engaged in the study of Korea. Reflecting the diversity of academic disciplines represented by its affiliated faculty and staff, the Center especially seeks to further interdisciplinary and intercultural studies. The Writings of Henry Cu Killl: Autobiography with Commentaries on Syngman Rhee, Pak Yong-man, and Chong Sun-man Edited and Translated, with an Introduction, by Dae-Sook Suh Paper No. 13 University of Hawaii Press Center for Korean Studies University of Hawaii ©Copyright 1987 by the University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kim, Henry Cu, 1889-1967. The Writings of Henry Cu Kim. (Paper; no. 13) Translated from holographs written in Korean. Includes index. 1. Kim, Henry Cu, 1889-1967. 2. Kim, Henry Cu, 1889-1967-Friends and associates. 3. Rhee, Syngman, 1875-1965. 4. Pak, Yong-man, 1881-1928. 5. Chong, Sun-man. 6. Koreans-Hawaii-Biography. 7. Nationalists -Korea-Biography. I. Suh, Dae-Sook, 1931- . II. Title. III. Series: Paper (University of Hawaii at Manoa.