AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE INTERPRETERS and the DEAF/HARD of HEARING COMMUNITY: NEGOTIATING SOCIAL JUSTICE and POWER DYNAMICS a Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montclarion Student Newspapers

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons The Montclarion Student Newspapers 1-31-2019 The Montclarion, January 31, 2019 The Montclarion Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/montclarion Recommended Citation The Montclarion, "The Montclarion, January 31, 2019" (2019). The Montclarion. 1331. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/montclarion/1331 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Montclair State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Montclarion by an authorized administrator of Montclair State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. themontclarion.org The Montclarion themontclarion @themontclarion themontclarion The Montclarion #MSUStudentVoice Since 1928 Volume XXIX, Issue 15 Thursday, January 31, 2019 themontclarion.org Bohn Hall Montclair State Ranked in Top 25 Most Floods on LGBTQ-Friendly College Campuses in US First Day Adrianna Caraballo University places 24th in “Top 25 LGBTQ-Friendly Colleges for 2019” list Assistant News Editor Montclair State University sent out an alert to students via text message along with a no- tice of room changes on Canvas due to a pipe burst in Bohn Hall on the first day of classes. Many classes had to change their schedules due to signifi- cant leakage. Some professors even had to relocate their class- es in the middle of their lesson, including professor Bridget Brown, who was teaching her writing course. “We evacuated [room 492] when the fire alarm went off and then were directed to re- enter,” Brown said. “But at that point, water was cascad- ing down from the ceiling in the hallway between the class- rooms.” Brown said she and one her students were fortunate enough to grab their belongings after an inch of water already covered the floor of the classroom. -

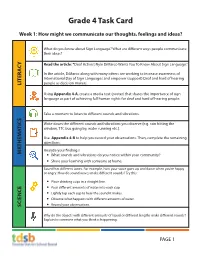

Literacy and Numeracy Virtual Learning Grade 4

Grade 4 Task Card Week 1: How might we communicate our thoughts, feelings and ideas? What do you know about Sign Language? What are different ways people communicate their ideas? Y Read the article: “Deaf Activist Nyle DiMarco Wants You To Know About Sign Language.” C A In the article, DiMarco along with many others are working to increase awareness of International Day of Sign Languages and empower (support) Deaf and hard of hearing people as decision makers. LITER Using Appendix 4-A, create a media text (poster) that shares the importance of sign language as part of achieving full human rights for deaf and hard of hearing people. Take a moment to listen to different sounds and vibrations. Write down the different sounds and vibrations you observe (e.g. rain hitting the TICS window, TTC bus going by, water running etc.). A Use Appendix 4-B to help you record your observations. Then, complete the remaining questions. THEM A Analyze your findings! M y What sounds and vibrations do you notice within your community? y Share your learning with someone at home. Sound has different tones. For example, how your voice goes up and down when you’re happy or angry. How do sound waves make different sounds? Try this: y Place drinking cups in a straight line. y Pour different amounts of water into each cup. y Lightly tap each cup to hear the sound it makes. y Observe what happens with different amounts of water. y Record your observations. SCIENCE Why do the objects with different amounts of liquid or different lengths make different sounds? Explain to someone what you think is happening. -

How to Be an Antiracist Ibram X. Kendi Is a #1 New York Times Bestselling and National Book Award-Winning Author

UNCW Leadership Lecture Series 2020-2021 Season COVID-19 Ibram X. Kendi- How To Be An AntiRacist Ibram X. Kendi is a #1 New York Times bestselling and National Book Award-winning author. His relentless and passionate research puts into question the notion of a post-racial society and opens readers’ and audiences’ eyes to the reality of racism in America today. Kendi’s lectures are sharp, informative, and hopeful, serving as a strong platform for any institution’s discussions on racism and being antiracist. Ibram X. Kendi is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University, and the founding director of the BU Center for Antiracist Research. Kendi is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and a CBS News correspondent. He will also become the 2020-2021 Frances B. Cashin Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for the Advanced Study at Harvard University. Kendi is the author of Stamped from the Begining: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, and The Black Campus Movement, which won the W.E.B. Du Bois Book Prize. He is also the author of the #1 New York Times bestsellers, How to Be an Antiracist, and Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, a young adult remix of Stamped from the Beginning, co- authored with Jason Reynolds. He most recently authored the #1 Indie bestseller, Antiracist Baby, available as a board book and picture book for caretakers and little ones 2019-2020 Season Tarana Burke Tarana Burke shares the heartbreaking story behind the genesis of the viral 2017 TIME Person Of The Year-winning ‘me too’ movement and gives strength and healing to those who have experienced sexual trauma or harassment. -

KEY CONCEPTS Embracing Black ASL As Has Been Mentioned Multiple Times in the Film, Black ASL Has Historically Been Characterized As “Less Than” White ASL

CHAPTER 7: LEGACY (25:02-26:38) This section looks towards the future and discusses how the Black Deaf community would like to see Black ASL understood and treated. KEY CONCEPTS Embracing Black ASL As has been mentioned multiple times in the film, Black ASL has historically been characterized as “less than” White ASL. Newer narratives, however, have begun to characterize Black ASL as “hip” or “cool,” a cultural object of value. While it is heartening to see that positive perceptions of Black ASL are emerging, it is important to embrace Black ASL for more than just its “coolness.” More education and greater public awareness regarding Black ASL will allow people to understand it better and embrace it as a valuable, systematic, legitimate, culturally and historically grounded language variety. “I want people to recognize this, that this is what we live for … to share our story and to show that our experience is valid.” -Felicia Williams, educator “It’s soul; it’s unity; there’s history; there’s culture. All of that is encapsulated into this thing we call ‘Black ASL’....when you understand Black ASL, you see us.” -Shentara Cobb, student 2 COMMON MISCONCEPTION the truth is people may think Black ASL is not a language indicative of ignorance or a lack of education! Rather, it is a systematic and Black ASL is a language of legitimate language ignorance or laziness grounded in a rich cultural history. LINGUISTIC CONCENSUS: Black ASL should be understood not as something that is “less than” White ASL but as something that has a rich history and culture--something that is valued. -

EQUALITY MICHIGAN SHARES 'BIGGER and BOLDER' AGENDA Four Key To-Dos for the LGBTQ Community Across the State

State Settles Same- Sex Adoption Case Dido Has Stories She Might Tell You Famika Edmond Named Black AIDS Institute Detroit Ambassador EQUALITY MICHIGAN SHARES 'BIGGER AND BOLDER' AGENDA Four Key To-Dos for the LGBTQ Community Across the State PRIDESOURCE.COMPRIDESOURCE.COM MARCH 28, 2019 | VOL. 2713 | FREE Natalie Cole LIVE SHOW The Many Illusions of DRAG Natalie Cole’s All Star Revue General Admission at door $22 Featuring emcee Natalie Cole | Dominique Polo | Bent- VIP seating & Meet & Greet DOORS 7:30 PM $35 ley James | Sir Walt | Raven Divine General Admission $20 online | VIP $35 online at Sounds by DJ ROME https://app.gopassage.com/events/natalie-cole-s-all-star-re- Live Vocals by Mae James vue-and-birthday-party Fine Artists Juniper Fleming, Sanda Cook, Friday, April 12, Showtime 10 p.m. Alan Watson, Luke McGilvray, Barbara Troy, Fine Art Show at 7:30 p.m. Ashlee Lori Will Free Parking – All ages welcome! Benefit Performance for Rebel Dog Rescue Detroit – Bring a can of dog food or cash to save the streetdogs. Senate Theater 6424 Michigan Ave., Detroit 2 BTL | March 28, 2019 www.PrideSource.com VOL. 2713 • MARCH 28, 2019 • ISSUE 1104 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL Editor in Chief 8 Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] Feature News Editor Kate Opalewski, 734.293.7200 x 108 [email protected] Editorial Assistant Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 16 22 [email protected] News & Feature Writers Emell Derra Adolphus, Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, Michelle E. -

Historic Preservation

HISTORIC PRESERVATION VOL 31, NO. 15 JAN. 6, 2016 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com A tale of two men and a house Robert Neal and Edgar Hellum. Photo courtesy of Mineral Point Archives BY SCOTT C. MORGAN “We toured this house that was a 1830s mining cottage that was restored by Bob and Edgar in the 1930s,” said Kinnebrew It was a honeymoon journey through Wisconsin that inspired about the historic Cornish-modeled buildings now known as Evanston-based husband-and-wife team Rick Kinnebrew and the Pendarvis historic site. “We were more interested in their Martha Meyer to write Ten Dollar House. Pride Films and Plays story and how they had to be very discreet about their sexual presents the Chicago-area debut of the new play this month, orientation in the community.” which is very appropriate because an earlier version of the Kinnebrew said Neal and Hellum initially planned to run a work was previously submitted for one of the company’s many business selling antiques. Yet it was another of Neal and Hel- LGBTQ writing competitions. lum’s creations and other circumstances which helped turn The Wisconsin town of Mineral Point (located about 50 miles Mineral Point into an artsy tourist destination. southwest of Madison) sparked the imaginations of Kinnebrew “We were drawn to it as a love story,” said Kinnebrew, add- RETURN OF THE MACK and Meyer when they first learned of the late gay couple Rob- ing that he and Meyer also have friends and family members Androgynous model Mack Dihle makes waves. ert Neal and Edgar Hellum. -

Yearin R Eview

R EA IN CHARLESTON Y COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT – R 2017 2018 E V I E W INTRODUCTION There is much to celebrate as we look back on the 2017-18 school year in Charleston County. The hard work, dedication, and commitment of every member of the CCSD family is evident in all of our triumphs and challenges. All of our gains are a result of the commitment from our CCSD family to ensure that every single day, students are the heart of our work. This year we celebrate numerous accomplishments on the individual, school, and district level by our talented students and staff. To begin, the district's Early College High School program completed its inaugural year with great success, while the district as a whole saw improvement in reading and math scores in 11 of 12 grades on the 2018 state accountability tests. We had schools selected as Capturing Kids' Hearts National showcase schools, Project Lead the Way Distinguished Schools, a National School to Watch, and a National Blue Ribbon School. Burke High earned the Best in Network Award from New Tech Network in its first year of the program and our teacher vacancies have continued to drop to their lowest level in years through increased retention, attraction, and reward measures the Board of Trustees and district have supported. Additionally, the district developed and approved a new five-year strategic plan with the help and input of its various stakeholders and sought its first- ever district-wide accreditation from a national agency. On the whole, we are seeing more students in work-based learning, internships, and apprenticeships, as well as in Advanced Placement courses Gerrita Postlewait surpassing the nation's above in pass rate. -

To Download The

Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTE VEDRA October 1, 2020 RNot yourecor average newspaper, not your average reader Volume 51, No. 48 der 75 cents PonteVedraRecorder.com IN FULL SWING Nease graduate Tyler McCumber hits a shot during the Corales Puntacana Championship last weekend. McCumber had a career-best finish with a total 271 to place second at the tournament. Read more in Sports on page 28. Photo provided by PGA TOUR/Andy Lyons with Getty Images What’s Available NOW On Ponte Vedra Recorder · October 1, 2020 CONNECTIONS 11 INSIDE: CHECK IT OUT! The Recorder’s Entertainment “Movie: The Forty-Year-Old “The Haunting of Bly Manor” “Deaf U” This coming-of-age documentary series Version” “The School Nurse Files” The latest chapter in “The Haunting” Radha (writer/director Radha Blank) is a from executive producers Eric Evangelista, From South Korea comes this comedy anthology series from creators Mike down-on-her-luck playwright desperate Shannon Evangelista, Nyle DiMarco and series about a young nurse with an Flanagan and Trevor Macy delves into Brandon Panaligan takes an unfiltered to pen her breakthrough script before apparent ability to chase ghosts, who is the mystery behind a gothic manor with turning 40. When she seemingly blows her look at a tight-knit group of students at hired to work at a high school beset by Connections centuries of dark secrets of love and loss Gallaudet University, a renowned private last opportunity, she reinvents herself as mysterious secrets and occurrences. Yu-mi and the people who inhabit it. Henry college for the deaf and hard of hearing a rapper and then finds herself vacillating Jung, Joo-Hyuk Nam, Dylan J. -

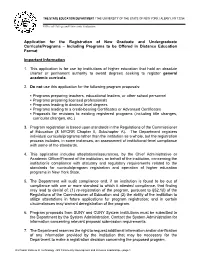

Including Programs to Be Offered in Distance Education Format

THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT / THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK / ALBANY, NY 12234 Office of College and University Evaluation Application for the Registration of New Graduate and Undergraduate Curricula/Programs – Including Programs to be Offered in Distance Education Format Important Information 1. This application is for use by institutions of higher education that hold an absolute charter or permanent authority to award degrees seeking to register general academic curricula. 2. Do not use this application for the following program proposals: . Programs preparing teachers, educational leaders, or other school personnel . Programs preparing licensed professionals . Programs leading to doctoral level degrees . Programs leading to a credit-bearing Certificates or Advanced Certificates . Proposals for revisions to existing registered programs (including title changes, curricular changes, etc.) 3. Program registration is based upon standards in the Regulations of the Commissioner of Education (8 NYCRR Chapter II, Subchapter A). The Department registers individual curricula/programs rather than the institution as a whole, but the registration process includes, in some instances, an assessment of institutional-level compliance with some of the standards. 4. This application includes attestations/assurances, by the Chief Administrative or Academic Officer/Provost of the institution, on behalf of the institution, concerning the institution’s compliance with statutory and regulatory requirements related to the standards for curricula/program -

Legacy | Change

LEGACY | CHANGE INCLUSIVENESS AND DIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2018 On the 50th anniversary of Kutak Rock: “We have preserved our On the 25th anniversary of Legacy culture and values. The convic- Kutak Rock: “We are charged tion, captured in the firm’s original with serving society in the charter, that respect and diversity pursuit of justice for all. To create a more instructive, collabo- put it simply, we are expected Kutak Rock LLP dedicates its 2018 rative and welcoming work envi- to put something back for that ronment, has remained a core part which we take out.” Inclusiveness and Diversity Annual of our firm.” Report to Harold Rock and David Jacobson and the legacy they created of mutual respect, inclusion, and diversity in the firm, with clients, and in our communities. Harold Rock David Jacobson Founder of Kutak Rock LLP Chair of Kutak Rock LLP, 1996-2017 (1932-2018) (1948-2018) Kutak Rock Inclusiveness and Diversity Annual Report 2018 Page 2 Reflections 2018 marked the passing of firm founder, Harold Rock, and long-time firm chair, David Jacobson. In reflecting on their legacies, inclusive- ness and respect are constant themes, beginning with a mandate in the founding charter that all relationships in the firm and with clients be based on mutual respect. Those who worked closely with Harold Rock describe him as a “trailblazer” who prioritized inclusiveness, diversity, and respect and hired diverse professionals from the firm’s inception. As David Jacobson noted on the 50th anniversary of the firm, “Our founders set the bar high when our doors opened over 50 years ago. -

Title Republished Last Mod Date Author Section Visitors Views Engaged Minut % New Vis % New Views Minutes Per Ne Minutes Per R

# Title Republished Last Mod Date Author Section Visitors Views Engaged Minut % New Vis % New Views Minutes Per Ne Minutes Per Ret Days Pub in Peri Visitors Per Day Views Per Day L Shares Tags 1 ‘Making a Murderer': Where Are They Now? (Photos) 2016-01-05 13: Tony Maglio Photos 178,004 3,413,345 346,154 85% 85% 1.9 1.8 113 1,569 30,089 594 steven avery,making a murderer,brendan dassey,netflix 2 45 First Looks at New TV Shows From the 2015-2016 Season 2015-05-07 21: Wrap Staff Photos 114,174 2,414,328 161,889 93% 92% 1.3 1.6 119 959 20,288 7 3 9 ‘Making a Murderer’ Memes That Will Make You Laugh While You Seethe 2016-01-04 16: Reid Nakamura Photos 248,427 2,034,710 171,881 87% 86% 0.7 0.7 114 2,173 17,800 726 making a murderer,netflix 4 Hollywood’s Notable Deaths of 2016 (Photos) 2016-01-11 10: Jeremy Fuster Movies 137,711 1,852,952 158,816 91% 92% 1.1 1 108 1,280 17,227 375 george gaynes,ken howard,joe garagiola,malik taylor,sian blake,frank sinatra jr.,abe vigoda,pat harrington jr.,garry shandling,obituary,craig strickland,vilmos zsigmond,pf 5 Hollywood’s Notable Deaths of 2015 (Photos) 2015-01-08 20: Wrap Staff Movies 27,377 1,112,257 83,702 92% 92% 3 2.9 119 230 9,347 40 lesley gore,hollywood notable deaths,brooke mccarter,uggie,robert loggia,rose siggins,rod taylor,edward herrmann,mary ellen trainor,stuart scott,holly woodlawn,wayn 6 ‘Making a Murderer': 9 Updates in Steven Avery’s Case Since the Premiere (Photos) 2016-01-13 13: Tim Kenneally Crime 134,526 1,093,825 148,880 86% 87% 1.1 1 105 1,276 10,373 224 netflix,laura ricciardi,making -

THE SMALL PRICE of SURVIVAL Alums Took to Court and Field at Ventable

MAGAZINE UCONNSEPT 2016 14 MISSION TO MARS: IT’S MORE THAN JUST ROCKET SCIENCE 26 A PEOPLE’S MUSEUM: 50 YEARS OF ART AT THE BENTON THE SMALL PRICE 32 ARE DEAF CHILDREN LOSING THEIR LANGUAGE? OF SURVIVAL 38 What Doug Casa Wants FIRST THERE WAS SHIRLEY CHISHOLM Every Parent to Know p.18 SEPTEMBER 2016 SNAP! Living Large UConn’s newest residence hall opened its doors to more than 700 undergraduates last month. The eight-story Next Generation Connecticut Hall (NextGen Hall) is the first new on-campus housing in 13 years and is one of the tallest buildings in Storrs, with a commanding view on all sides. Innovation and creativity are built into the design of the 210,000-square-foot residence hall: On the first floor is an Idea Lab tailored for students to learn together and work in teams to solve problems and an Innovation Zone, or ‘maker space,’ complete with a mobile white board, a textile station, laser cutter, and 3-D printer. For more on NextGen Hall and to see a photo gallery of campus housing through the years, go to s.uconn.edu/dorms. UCONN MAGAZINE | MAGAZINE.UCONN.EDU SEPTEMBER 2016 CONTENTS | SEPTEMBER 2016 VOL. 17 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2016 | CONTENTS FROM THE EDITOR In the video, you see her, a 17-year-old girl playing one of the last games of her high WEB school volleyball career, serve the ball, take a step back and then, inexplicably, drop to EXCLUSIVES the floor. Out cold. People rush to her aid, try to revive her with CPR, to no avail.