A Study Into the Sexual Nature of the Goddess Inanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Akkadian Empire

RESTRICTED https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/the-akkadian-empire/ The Akkadian Empire LEARNING OBJECTIVE • Describe the key political characteristics of the Akkadian Empire KEY POINTS • The Akkadian Empire was an ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia, which united all the indigenous Akkadian speaking Semites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule within a multilingual empire. • King Sargon, the founder of the empire, conquered several regions in Mesopotamia and consolidated his power by instating Akaddian officials in new territories. He extended trade across Mesopotamia and strengthened the economy through rain-fed agriculture in northern Mesopotamia. • The Akkadian Empire experienced a period of successful conquest under Naram-Sin due to benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses, and the confiscation of wealth. • The empire collapsed after the invasion of the Gutians. Changing climatic conditions also contributed to internal rivalries and fragmentation, and the empire eventually split into the Assyrian Empire in the north and the Babylonian empire in the south. TERMS Gutians A group of barbarians from the Zagros Mountains who invaded the Akkadian Empire and contributed to its collapse. Sargon The first king of the Akkadians. He conquered many of the surrounding regions to establish the massive multilingual empire. Akkadian Empire An ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia. Cuneiform One of the earliest known systems of writing, distinguished by its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, and made by means of a blunt reed for a stylus. Semites RESTRICTED Today, the word “Semite” may be used to refer to any member of any of a number of peoples of ancient Southwest Asian descent, including the Akkadians, Phoenicians, Hebrews (Jews), Arabs, and their descendants. -

1 Inanna Research Script

INANNA RESEARCH SCRIPT (to be cut and shaped for performance) By Peggy Firestone Based on Translations of Clay Tablets from Sumer By Samuel Noah Kramer 1 [email protected] (773) 384-5802 © 2008 CAST OF CHARACTERS In order of appearance Narrators ………………………………… Storytellers & Timekeepers Inanna …………………………………… Queen of Heaven and Earth, Goddess, Immortal Enki ……………………………………… Creator & Organizer of Earth’s Living Things, Manager of the Gods & Goddesses, Trickster God, Inanna’s Grandfather An ………………………………………. The Sky God Ki ………………………………………. The Earth Goddess (also known as Ninhursag) Enlil …………………………………….. The Air God, inventor of all things useful in the Universe Nanna-Sin ………………………………. The Moon God, Immortal, Father of Inanna Ningal …………………………………... The Moon Goddess, Immortal, Mother of Inanna Lilith ……………………………………. Demon of Desolation, Protector of Freedom Anzu Bird ………………………………. An Unholy (Holy) Trinity … Demon bird, Protector of Cattle Snake that has no Grace ………………. Tyrant Protector Snake Gilgamesh ……………………………….. Hero, Mortal, Inanna’s first cousin, Demi-God of Uruk Isimud ………………………………….. Enki’s Janus-faced messenger Ninshubur ……………………………… Inanna’s lieutenant, Goddess of the Rising Sun, Queen of the East Lahamma Enkums ………………………………… Monster Guardians of Enki’s Shrine House Giants of Eridu Utu ……………………………………… Sun God, Inanna’s Brother Dumuzi …………………………………. Shepherd King of Uruk, Inanna’s husband, Enki’s son by Situr, the Sheep Goddess Neti ……………………………………… Gatekeeper to the Nether World Ereshkigal ……………………………. Queen of the -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Ancient Mesopotamia Akkdadian Empire Reading Comprehension

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA AKKDADIAN EMPIRE READING COMPREHENSION *Article *10 Matching Questions *10 True/False Questions *4 Multiple Choice Questions *Key Included Name____________________ ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA- AKKADIAN EMPIRE The Akkadian Empire was the first Empire to rule all of Mesopotamia. It lasted about 200 years from 2300 BC to 2100 BC. Originally the Sumerians lived in the southern part of Mesopotamia and the Akkadians lived in the northern part. They had similar governments and cultures, but spoke different languages. The governments had individual city-states, where each city had its own ruler that controlled the city and the surrounding area. The city-states were not initially united and often warred with one another. Eventually, the Akkadian rulers started to see the advantage to uniting many of their cities under a single nation and began forming alliances to work together. Sargon the Great rose to power around 2300 BC. According to Sumerian literature, Sargon was born to an Akkadian high priestess and a poor father, maybe a gardener. His mother abandoned him by putting him a reed woven basket and let it float down the river, like Moses a thousand years later. Sargon was rescued and made friends with the goddess Ishtar and was brought up in the king’s court. Sargon built himself a new city at Akkad and made himself the king of it when he grew up. He gradually conquered all the land around it, making the Akkadian Empire. The powerful Sumerian city of Uruk attacked Akkad, but they fought back and eventually conquered Uruk. Sargon went on to conquer all of the Sumerian city-states and united northern and southern Mesopotamia under a single ruler. -

AP World History the Epic of Gilgamesh Considering the Evidence

AP World History The Epic of Gilgamesh August 17, 2011 Considering the Evidence: Life and Afterlife in Mesopotamia and Egypt The advent of writing was not only a central The epic poem itself recounts the adventures of feature of the First Civilizations but also a great Gilgamesh, said to he part human and part divine. boon to later historians. Access to early written As the story opens, he is the energetic and yet records from these civilizations allows us some oppressive ruler of Uruk. The pleas of his people insight, in their own words, as to how these persuade the gods to send Enkidu, an uncivilized ancient peoples thought about their societies and man from the wilderness, to counteract this their place in the larger scheme of things. Such oppression. But before he can confront the erring documents, of course, tell only a small part of the monarch, Enkidu must become civilized, a process story, for they most often reflect the thinking of that occurs at the hands of a seductive harlot. the literate few—usually male, upper-class, When the two men finally meet, they engage in a powerful, and well-to-do—rather than the outlook titanic wrestling match from which Gilgamesh of the vast majority who lacked such privileged emerges victorious. Thereafter they bond in a deep positions. Nonetheless, historians have been friendship and undertake a series of adventures grateful for even this limited window on the life of together. In the course of these adventures, they at least some of our ancient ancestors. offend the gods, who then determine that Enkidu must die. -

Gilgamesh Sung in Ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East

Gilgamesh sung in ancient Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Ancient Near East Dr. Le4cia R. Rodriguez 20.09.2017 ì The Ancient Near East Cuneiform cuneus = wedge Anadolu Medeniyetleri Müzesi, Ankara Babylonian deed of sale. ca. 1750 BCE. Tablet of Sargon of Akkad, Assyrian Tablet with love poem, Sumerian, 2037-2029 BCE 19th-18th centuries BCE *Gilgamesh was an historic figure, King of Uruk, in Sumeria, ca. 2800/2700 BCE (?), and great builder of temples and ci4es. *Stories about Gilgamesh, oral poems, were eventually wriXen down. *The Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh compiled from 73 tablets in various languages. *Tablets discovered in the mid-19th century and con4nue to be translated. Hero overpowering a lion, relief from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), Iraq, ca. 721–705 BCE The Flood Tablet, 11th tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Library of Ashurbanipal Neo-Assyrian, 7th century BCE, The Bri4sh Museum American Dad Gilgamesh and Enkidu flank the fleeing Humbaba, cylinder seal Neo-Assyrian ca. 8th century BCE, 2.8cm x 1.3cm, The Bri4sh Museum DOUBLING/TWINS BROMANCE *Role of divinity in everyday life. *Relaonship between divine and ruler. *Ruler’s asser4on of dominance and quest for ‘immortality’. StatuePes of two worshipers from Abu Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Iraq, ca. 2700 BCE. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone, male figure 2’ 6” high. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. URUK (WARKA) Remains of the White Temple on its ziggurat. Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. 3500–3000 BCE. Plan and ReconstrucVon drawing of the White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), Iraq, ca. -

NINAZU, the PERSONAL DEITY of GUDEA Toshiko KOBAYASHI*

NINAZU, THE PERSONAL DEITY OF GUDEA -The Continuity of Personal Deity of Rulers on the Royal Inscriptions of Lagash- Toshiko KOBAYASHI* I. Introduction 1. Historical materials from later periods For many years, I have examined the personal deities of rulers in Pre- Sargonic Lagash.(1) There are not many historical materials about the personal deities from Pre-Sargonic times. In as much as the materials are limited chiefly to the personal deities recorded in the royal inscriptions, not all aspects of personal deities are clear. In my paper "On Ninazu, as Seen in the Economic Texts of the Early Dynastic Lagas (1)" in Orient XXVIII, I discussed Ninazu, who appears in the administrative-economic texts of Pre-Sargonic Lagash. Ninazu appears only in the offering-lists in the reign of Uruinimgina, the last ruler of Pre-Sargonic Lagash. Based only on an analysis of the offering-lists, I argued that Ninazu was the personal deity of a close relative of Uruinimgina. In my investigation thus far of the extant historical materials from Pre-Sargonic Lagash, I have not found any royal inscriptions and administrative-economic texts that refer to Ninazu as dingir-ra-ni ("his deity"), that is, as his personal deity. However, in later historical materials two texts refer to Ninazu as "his deity."(2) One of the texts is FLP 2641,(3) a royal inscription by Gudea, engraved on a clay cone. The text states, "For his deity Ninazu, Gudea, ensi of Lagash, built his temple in Girsu." Gudea is one of the rulers belonging to prosperous Lagash in the Pre-Ur III period; that is, when the Akkad dynasty was in decline, after having been raided by Gutium. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

3 a Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36

3 A Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36 3.1 Introduction CCs may be classified according to a number of characteristics. Jagersma (2010, pp. 687-705) gives a detailed description of Sumerian CCs arranged according to the types of constituents that may function as S or PC. Jagersma’s description is the most detailed one ever written about CCs in Sumerian, and particularly, the parts on clauses with a non-finite verbal form as the PC are extremely insightful. Linguistic studies on CCs, however, discuss the kind of constituents in CCs only in connection with another kind of classification which appears to be more relevant to the description of CCs. This classification is based on the semantic properties of CCs, which in turn have a profound influence on their grammatical and pragmatic properties. In this chapter I will give a description of CCs based mainly on the work of Renaat Declerck (1988) (which itself owes much to Higgins [1979]), and Mikkelsen (2005). My description will also take into account the information structure of CCs. Information structure is understood as “a phenomenon of information packaging that responds to the immediate communicative needs of interlocutors” (Krifka, 2007, p. 13). CCs appear to be ideal for studying the role information packaging plays in Sumerian grammar. Their morphology and structure are much simpler than the morphology and structure of clauses with a non-copular finite verb, and there is a more transparent connection between their pragmatic characteristics and their structure. 3.2 The Classification of Copular Clauses in Linguistics CCs can be divided into three main types on the basis of their meaning: predicational, specificational, and equative. -

Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Western Kentucky University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2008 A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Craig, Leah Whitehead, "A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature" (2008). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 106. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/106 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Journey Into the Land of No Return: Death Attitudes and Perceptions of Death and Afterlife in Ancient Near Eastern Literature Leah Whitehead Craig Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of Western Kentucky University Spring, 2008 Approved by: _________________________________ _________________________________ -

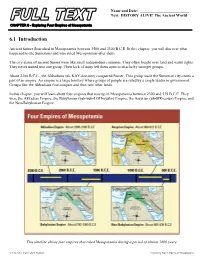

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

Inanna a Commentary on Scenes of the Play

Inanna A Commentary on Scenes of the Play What is an Archetype? ‘Archetype’ defies simple definition. The word comes from the Greek arche and tupos. Arche means ‘first principle’ i.e. the creative source which cannot be seen directly. Tupos means ‘impression’ i.e. one of many manifestations of the first principle. Carl Jung said: … their origin can only be explained by assuming them to be deposits [in the unconscious] of the constantly repeated experiences of humanity. (CW7:109) It is an inherited tendency of the human mind to form representations of mythological motifs … that vary a great deal without losing their basic pattern … this tendency is instinctive, like the specific impulse of nest-building, migration, etc. in birds. (CW18:52) The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences. (CW 8: 230) The contents of the collective unconscious are not only residues of archaic specifically human modes of functioning, but also the residues of functions from [our] animal ancestry … (CW7:159) Inanna and the pantheon of gods and goddesses are universally imagined concepts that emerge from the silt of the Unconscious. They serve as beacons that point the way in a life that is vast and lonely. From the beginning of time, humans have dreamt with desire and fear about their forebears: their mothers, fathers and children; their wise elders, their kings and queens, heroes, princes and princesses; martyrs, saints, demons and fools. The procession of emotionally laden images is endless.