Vocal Ornamentation in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

7Th GRADE ORCHESTRA 7Th Grade Orchestra Is Offered to All Students Who Have Completed Fairfield Orchestra Skill Level III

7th GRADE ORCHESTRA 7th grade Orchestra is offered to all students who have completed Fairfield Orchestra Skill Level III. Instruction emphasizes instrumental techniques, ensemble rehearsal and performance techniques, and music reading. All orchestra students will receive a small group homogenous lesson once each week. Lessons will take place during the school day on a rotating pull-out basis with the orchestra director or FPS music teacher specializing in orchestra. Recommended lesson size is no more than 6 students. Homework for this class includes regular, consistent practice on assigned lesson and ensemble music. Participation in the Winter and Spring evening curricular concerts is expected and integral for successful completion of this class. 7th grade orchestra is a full year class that meets three times per week. Students electing Orchestra/Chorus will rehearse once per week in Chorus, and twice per week with an Orchestra class. Course Overview All students in the Fairfield Orchestra Program progress Course Goals Artistic Processes through an Ensemble Sequence and instrument specific Students will have the ability to understand • Create Skill Levels. and engage with music in a number of • Perform different ways, including the creative, • Respond Fairfield’s Orchestra Program Ensemble Sequence responsive and performative artistic • Connect processes. They will have the ability to Grade/Course Instrument Ensemble Sequence perform music in a manner that illustrates Anchor Standards Skill Level Marker careful preparation and reflects an • Select, analyze, and 4th Grade Novice understanding and interpretation of the I interpret artistic work for Orchestra selection. They will be musically literate. presentation. 5th Grade Novice II • Develop and refine artistic Orchestra Students will be artistically literate: they will techniques and work for th 6 Grade Intermediate have the knowledge and understanding presentation. -

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Pipa by Moshe Denburg.Pdf

Pipa • Pipa [ Picture of Pipa ] Description A pear shaped lute with 4 strings and 19 to 30 frets, it was introduced into China in the 4th century AD. The Pipa has become a prominent Chinese instrument used for instrumental music as well as accompaniment to a variety of song genres. It has a ringing ('bass-banjo' like) sound which articulates melodies and rhythms wonderfully and is capable of a wide variety of techniques and ornaments. Tuning The pipa is tuned, from highest (string #1) to lowest (string #4): a - e - d - A. In piano notation these notes correspond to: A37 - E 32 - D30 - A25 (where A37 is the A below middle C). Scordatura As with many stringed instruments, scordatura may be possible, but one needs to consult with the musician about it. Use of a capo is not part of the pipa tradition, though one may inquire as to its efficacy. Pipa Notation One can utilize western notation or Chinese. If western notation is utilized, many, if not all, Chinese musicians will annotate the music in Chinese notation, since this is their first choice. It may work well for the composer to notate in the western 5 line staff and add the Chinese numbers to it for them. This may be laborious, and it is not necessary for Chinese musicians, who are quite adept at both systems. In western notation one writes for the Pipa at pitch, utilizing the bass and treble clefs. In Chinese notation one utilizes the French Chevé number system (see entry: Chinese Notation). In traditional pipa notation there are many symbols that are utilized to call for specific techniques. -

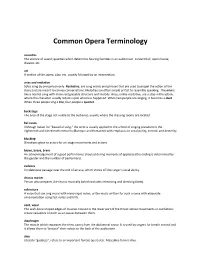

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

SMT Sweelinck Paper Text SHORT V2

SMT Graduate Workshop Peter Schubert: Renaissance Instrumental Music November 7, 2014 Derek Reme! Musical Architecture in Three Domains: Stretto, Suspension, and Diminution in Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia is among the most famous keyboard works of the sixteenth century.1 It served as a model for instrumental polyphony that was imitated throughout Europe in the seventeenth century.2 The fantasia's subject is treated in augmentation and diminution in four rhythmic levels and also in four-voice stretto. The initial stretto passage, which is repeated in diminution in the final climax of the piece, contains an unusual accented dissonance; in this style, accented dissonance is reserved only for suspensions. There are three metrical levels of suspensions used throughout the piece, which parallel the four rhythmic levels of the subject's augmentation and diminution – only a whole note suspension is missing. I propose that the unusual accented dissonance in the first four-voice stretto passage is actually a rearticulated whole note suspension, representing the missing fourth metrical level in that domain. Therefore, this stretto passage combines two domains at their fourth and most heightened level: stretto in four voices and suspension at the whole note. This passage also represents a structural "pillar," which, through its repetition, divides the piece into three large sections. In addition, the middle section contains two analogous "internal pillars," which further subdivide the middle into three subsections. The last large-scale section, the climax, introduces subject stretto at the eighth note level, or !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 Harold Vogel, "Sweelinck's 'Orfeo' Die 'Fantasia Crommatica,'" Musik in die Kirche, No. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick.