Keeping America Informed: the U.S. Government Printing Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Context and Taxonomy for Printing: Intersections of Culture and Technology, 1850-2000

A context and taxonomy for printing: Intersections of culture and technology, 1850-2000 This project is based upon a research funding application being made to the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the body responsible in the UK for funding University research in this area. It has been written by myself, Stephen Hoskins and Paul Thirkell in response to a series of discussions at the last AEPM General Meeting in Odense, Denmark and in particular response to Alan Marshall’s paper at that meeting. Unfortunately there have been problems in submitting this application, partly because of the pressures of daily life, which fall upon us all, but primarily because of the (AHRC) body closing its application process for 12 months and the ongoing funding crisis in UK universities. However the AHRC is now open to fresh bids, if there are still enough museums interested Research Context: As observed by Alan Marshall in 2008,1 ‘in the 1960s, before the extraordinary eruption of digital techniques in the graphic arts, no one, not even the best informed commentator could have imagined the desktop publishing and digital prepress techniques which we take for granted…’ Forty years later, we are in a position to put the apparently unique phenomenon of the digital revolution into its broader technological, historical and social perspective. However, there has been little analysis of the technical developments, social impacts, and market shifts that led up to the present domination of digital printing. The printing museum offers an entirely appropriate forum for understanding the core events that have culminated in the digital revolution. -

Other Printing Methods

FLEXO vs. OTHER PRINTING METHODS Web: www.luminite.com Phone: 888-545-2270 As the printing industry moves forward into 2020 and beyond, let’s take a fresh look at the technology available, how flexo has changed to meet consumer demand, and how 5 other popular printing methods compare. CONTENTS ● A History of Flexo Printing ● How Flexo Printing Works ● How Litho Printing Works ● How Digital Printing Works ● How Gravure Printing Works ● How Offset Printing Works ● What is Screen Printing? ● Corrugated Printing Considerations ● Flexo Hybrid Presses ● Ready to Get Started with Flexo? 2 A History of Flexo Printing The basic process of flexography dates back to the late 19th century. It was not nearly as refined, precise, or versatile as the flexo process today -- and can be best described as a high-tech method of rubber stamping. Printing capabilities were limited to very basic materials and designs, with other printing methods greatly outshining flexo. Over the past few decades flexo technology has continuously evolved. This is largely thanks to the integration of Direct Laser Engraving technology, advancements in image carrier materials, and in press technologies. These innovations, among others, have led to increased quality and precision in flexo products. These technological improvements have positioned flexography at the helm of consumer product and flexible packaging printing. Flexo is growing in popularity in a variety of other industries, too, including medical and pharmaceutical; school, home, and office products; and even publishing. How Flexo Printing Works Flexo typically utilizes an elastomer or polymer image carrier such as sleeves, cylinders, and plates. The image carrier is engraved or imaged to create the design for the final desired product. -

Open Society Archives

OSA book OSA / Publications OPEN SOCIETY ARCHIVES Open Society Archives Edited by Leszek Pudlowski and Iván Székely Published by the Open Society Archives at Central European University Budapest 1999 Copyright ©1999 by the Open Society Archives at Central European University, Budapest English Text Editor: Andy Haupert ISBN 963 85230 5 0 Design by Tamás Harsányi Printed by Gábor Rózsa Printing House, Budapest on Niveus acid-free offset printing paper of 90g/m2 produced by Neusiedler Szolnok Paper Mill, Hungary. This paper meets the requirements of ISO9706 standard. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. The coordinates of the Archives The enemy-archives (István Rév) 14 Archival parasailing (Trudy Huskamp Peterson) 20 Access to archives: a political issue (Charles Kecskeméti) 24 The Open Society Archives: a brief history (András Mink) 30 CHAPTER II. The holdings Introduction 38 http://www.osaarchivum.org/files/1999/osabook/BookText.htm[31-Jul-2009 08:07:32] OSA book COMMUNISM AND COLD WAR 39 Records of the Research Institute of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 39 • The Archives in Munich (András Mink) 39 • Archival arrangement and structure of the records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute (Leszek Pud½owski) 46 • The Information Resources Department 49 The East European Archives 49 Records of the Bulgarian Unit (Olga Zaslavskaya) 49 Records of the Czechoslovak Unit (Pavol Salamon) 51 Records of the Hungarian Unit (Csaba Szilágyi) 55 Records of the Polish Unit (Leszek Pud½owski) 58 Records of the Polish Underground Publications Unit -

The EMA Guide to Envelopes and Mailing

The EMA Guide to Envelopes & Mailing 1 Table of Contents I. History of the Envelope An Overview of Envelope Beginnings II. Introduction to the Envelope Envelope Construction and Types III. Standard Sizes and How They Originated The Beginning of Size Standardization IV. Envelope Construction, Seams and Flaps 1. Seam Construction 2. Glues and Flaps V. Selecting the Right Materials 1. Paper & Other Substrates 2. Window Film 3. Gums/Adhesives 4. Inks 5. Envelope Storage 6. Envelope Materials and the Environment 7. The Paper Industry and the Environment VI. Talking with an Envelope Manufacturer How to Get the Best Finished Product VII. Working with the Postal Service Finding the Information You Need VIII. Final Thoughts IX. Glossary of Terms 2 Forward – The EMA Guide to Envelopes & Mailing The envelope is only a folded piece of paper yet it is an important part of our national communications system. The power of the envelope is the power to touch someone else in a very personal way. The envelope has been used to convey important messages of national interest or just to say “hello.” It may contain a greeting card sent to a friend or relative, a bill or other important notice. The envelope never bothers you during the dinner hour nor does it shout at you in the middle of a television program. The envelope is a silent messenger – a very personal way to tell someone you care or get them interested in your product or service. Many people purchase envelopes over the counter and have never stopped to think about everything that goes into the production of an envelope. -

Triangle Accordion Books Part 2

“Part Two: Assembling the book” Time from start to finish = 1 hour You will need the following materials: • Heavy paper, which will be cut into three 4 5/8” X 20” strips, the best option is to cut these strips from one large 22” X 30” sheet of watercolor paper (this will be used for the inner “accordion” of the book) • 2 pieces of chipboard or thick cardboard, 6x6 inches each • Painted paper or scrapbooking paper at least 6x6 inches in size • Pencil • Ruler • Glue (regular white glue or glue sticks) • Clean scrap paper, computer paper or newsprint is good • X-acto Knife or scissors • Cutting matt (or a piece of scrap cardboard to protect your work surface) Brief description: The next part of our process is to measure, cut and assemble your book. This part is made up of several smaller steps within each major step and requires precise measurement and patience. For Part Two, I suggest making a cup of your favorite tea and putting on some relaxing music in the background. While, this may be the most challenging step for some, if you follow the instructions closely and don’t rush, you should come out of it with a fully assembled book ready for creative alteration and decoration! For those new to bookmaking here are a few helpful hints: • Measure! Measure! Measure!: Nothing is more disappointing than assembling several pieces only to find at the final step that they don’t quite fit, especially when you’re out of materials to try again! During this process, we will be measuring out strips of paper, then folding, cutting and gluing them together at specific points. -

Laughing Bear Newsletter 120

LAUGHING BEAR NEWSLETTER 120 March/April 2000; edited by Tom Person; Copyright 2000 by Laughing Bear Press; Estab. 1976; ISSN 1056-0327 P.O. Box 613322, Dallas, TX 75261-3322; 817-858-9515; e-mail: [email protected] http://www.laughingbear.com; Keyword: Laughing Bear; $15/12 issues, $17.50/Canada, £15/UK, Eire, $25/other The Surviving Small the middle of the run would be Computer To Plate acceptable. Plates for offset printing are Press: Before You Hire Now the question is: Who was made by first photographing each a Printer responsible for the print job being a page and developing the film. Years ago I worked for a com- disaster? Then a graphic artist “strips” the pany that dealt with the Army. One It was me. I got a bid on 4,000 film negatives onto frames. A project was to produce a full color books. I did not specifically say frame is a paper or polyester sheet comic book of tips for maintaining that I wanted 4,000 beautiful, with a hole cut into it for each page the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. usable books nor did I ask the to give the film more support and Since I the only person there with printer how much overage (wasted make it easier to handle, especially any publishing experience at all copies) we’d have to add to the run when there are several pages (and it was minimal at the time), I to get them. mounted (or “imposed”) for print- was chosen to find a printer. I assumed the printer knew ing the book “4 up”, “16 up”, etc. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

New Paris Telephone

2 www.the-papers.com — the PAPER — Tuesday, May 28, 2019 Rite Choice Foods ™ The right food at the right price KNOW YOUR NEIGHBOR Senior Citizens Discount Every Tuesday Receive 5% Off (Excluding Tobacco & Alcohol) PRICES GOOD MAY 30-JUNE 5, 2019 Executive director has LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1991 BY GARYARY MILLERMILLERL YOU NEVER KNOW THE DISCOUNTS 'LVFRXQW DAVE HAS IN STORE . %(6748$/,7< 'DYH CHECK OUT HIS LIMITED ITEMS ,7(06)25 IN STORE FOR DEEPER %(6735,&(6 DISCOUNTSDIS THAN ADVERTISED heart for at-risk kids PerfectP for Graduation Parties! 6% VANILLA AND CHOCOLATE %\/$85,(/(&+/,71(5 SOFT SERVE ICE CREAM MIX 6WDII:ULWHU 2.5 GALLON BAGS WILL MAKE 4 GALLONS IF YOU NEED 2-3 BAGS, CALL IN 574-773-5462 “I created a mentoring pro- ECKRICH JUMBO, REG., gram in Colorado,” stated Menes- BUN SIZE & CHEESE ¢ sah Nelson, Elkhart. “It was for HOT DOGS 14 OZ.79 youth, ages 12 to 22, involved in AWARD WINNING MEAT DEPARTMENT FOR YOUR GRILLING NEEDS the justice system. I also worked SOME OF THE BEST PRICES ON QUALITY STEAKS IN THE STATE OF INDIANA. LOOK AT OTHER STORES AND LOOK AT OUR PRICES ON for Child Protection Services. HOW MUCH YOU SAVE IN OUR AWARD WINNING MEAT DEPARTMENT I’ve always had a passion for FAMILY PACK $ 49 $ 99 young people who need some NEW YORK STRIP 5 LB. - WHOLE 4 LB. extra guidance. That’s why it’s BONELESS $ 79 been such a good fit for me at Big PORK CHOPS FAMILY PACK 2 LB. Brothers Big Sisters of Elkhart BONELESS $ 19 County. -

Introduction to Printing Technologies

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Introduction to Printing Technologies Study Material for Students : Introduction to Printing Technologies CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. Itfunctions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman,Edited with theproducer, trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor director, etc. To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 : Introduction to Printing Technologies INTRODUCTION The book introduces the students to fundamentals of printing. Today printing technology is a part of our everyday life. It is all around us. T h e history and origin of printing technology are also discussed in the book. Students of mass communication will also learn about t h e different types of printing and typography in this book. The book will also make a comparison between Traditional Printing Vs Modern Typography. -

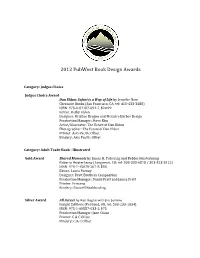

2012 Pubwest Book Design Awards

2012 PubWest Book Design Awards Category: Judges Choice Judges Choice Award Dan Eldon: Safari is a Way of Life by Jennifer New Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA; tel: 415-433-3488) ISBN: 978-0-81187-091-7, $24.99 Editor: Kathy Eldon Designer: Kristine Brogno and McGuire Barber Design Production Manager: Steve Kim Artist/Illustrator: The Estate of Dan Eldon Photographer: The Estate of Dan Eldon Printer: Asia Pacific Offset Bindery: Asia Pacific Offset Category: Adult Trade Book - Illustrated Gold Award Shared Moments by James H. Pickering and Bobbie Heisterkamp Roberta Heisterkamp (Longmont, CO; tel: 303-333-6818 / 303-823-5122) ISBN: 978-1-45078-207-8, $80 Editor: Laura Furney Designer: Pratt Brothers Composition Production Manager: Daniel Pratt and James Pratt Printer: Friesens Bindery: Roswell Bookbinding Silver Award All Access by Ken Regan with Jim Jerome Insight Editions (Portland, OR; tel: 503-233-1834) ISBN: 978-1-60887-033-2, $75 Production Manager: Jane Chinn Printer: C & C Offset Bindery: C & C Offset Bronze Award Harry Potter: Page to Screen by Bob McCabe Insight Editions (San Rafael, CA; tel: 415-526-1370) ISBN: 978-0-06210-189-1, $75 Editor: Jake Gerli Designer: Jason Babler, Christine Kwasnik, Dasha Trojounek, Jenelle Wagner Production Manager: Anna Wan Artist/Illustrator: Warner Brothers Photographer: Warner Brothers Printer: Great Wall Printing Bindery: Great Wall Printing Category: Adult Trade Book - Non- Illustrated Gold Award Intersecting Sets: A Poet Looks at Science by Alice Major University of Alberta Press (Edmonton, AB; tel: 780-492-3662) ISBN: 978-0-88864-595-1, $29.95 Editor: Meaghan Craven Designer: Alan Brownoff Production Manager: Alan Brownoff Printer: McCallum Printing Group Inc. -

Disclosure Guide

WEEKS® 2021 - 2022 DISCLOSURE GUIDE This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions, and the use of, the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. 0490-2021 RCI, TRC 2021-2022 Annual Disclosure Guide Covers.indd 5 5/20/21 10:34 AM DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Fiona G. Downing EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President 14 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide to the RCI Weeks Exchange Program (“Disclosure Guide”) explains the RCI Weeks Elizabeth Dreyer Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Senior Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer, and LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Manager this information to ensure full understanding of the 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Julia A. Frey herein, capitalized terms in this Disclosure Guide have the Assistant Secretary same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are made a part of this document. Brian Gray Vice President RCI is the owner and operator of the RCI Weeks 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Exchange Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Gary Green Senior Vice President RCI is a Delaware limited liability company (registered as 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32821 Resort Condominiums -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government.