Understanding Cooperation in the Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: a “How To” Manual *

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: A “How To” Manual * Daniel Byman and Matthew Kroenig Security Studies (forthcoming, June 2016) *For helpful comments on earlier versios of this article, the authors would like to thank Michael C. Desch, Rebecca Friedman, Bruce Jentleson, Morgan Kaplan, Marc Lynch, Jeremy Shapiro, and participants in the Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security Speaker Series at the University of Chicago, participants in the Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Launch Conference, Austin, Texas, October 17-19, 2013, and members of a Midwest Political Science Association panel. Particular thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Security Studies for their helpful comments. 1 Joseph Nye, one of the rare top scholars with experience as a senior policymaker, lamented “the walls surrounding the ivory tower never seemed so high” – a view shared outside the academy and by many academics working on national security.1 Moreover, this problem may only be getting worse: a 2011 survey found that 85 percent of scholars believe the divide between scholars’ and policymakers’ worlds is growing. 2 Explanations range from the busyness of policymakers’ schedules, a disciplinary shift that emphasizes theory and methodology over policy relevance, and generally impenetrable academic prose. These and other explanations have merit, but such recommendations fail to recognize another fundamental issue: even those academic works that avoid these pitfalls rarely shape policy.3 Of course, much academic research is not designed to influence policy in the first place. The primary purpose of academic research is not, nor should it be, to shape policy, but to expand the frontiers of human knowledge. -

John J. Mearsheimer: an Offensive Realist Between Geopolitics and Power

John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power Peter Toft Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Østerfarimagsgade 5, DK 1019 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] With a number of controversial publications behind him and not least his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John J. Mearsheimer has firmly established himself as one of the leading contributors to the realist tradition in the study of international relations since Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. Mearsheimer’s main innovation is his theory of ‘offensive realism’ that seeks to re-formulate Kenneth Waltz’s structural realist theory to explain from a struc- tural point of departure the sheer amount of international aggression, which may be hard to reconcile with Waltz’s more defensive realism. In this article, I focus on whether Mearsheimer succeeds in this endeavour. I argue that, despite certain weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s theoretical and empirical work represents an important addition to Waltz’s theory. Mearsheimer’s workis remarkablyclear and consistent and provides compelling answers to why, tragically, aggressive state strategies are a rational answer to life in the international system. Furthermore, Mearsheimer makes important additions to structural alliance theory and offers new important insights into the role of power and geography in world politics. Journal of International Relations and Development (2005) 8, 381–408. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065 Keywords: great power politics; international security; John J. Mearsheimer; offensive realism; realism; security studies Introduction Dangerous security competition will inevitably re-emerge in post-Cold War Europe and Asia.1 International institutions cannot produce peace. -

International Relations in a Changing World: a New Diplomacy? Edward Finn

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN A CHANGING WORLD: A NEW DIPLOMACY? EDWARD FINN Edward Finn is studying Comparative Literature in Latin and French at Princeton University. INTRODUCTION The revolutionary power of technology to change reality forces us to re-examine our understanding of the international political system. On a fundamental level, we must begin with the classic international relations debate between realism and liberalism, well summarised by Stephen Walt.1 The third paradigm of constructivism provides the key for combining aspects of both liberalism and realism into a cohesive prediction for the political future. The erosion of sovereignty goes hand in hand with the burgeoning Information Age’s seemingly unstoppable mechanism for breaking down physical boundaries and the conceptual systems grounded upon them. Classical realism fails because of its fundamental assumption of the traditional sovereignty of the actors in its system. Liberalism cannot adequately quantify the nebulous connection between prosperity and freedom, which it assumes as an inherent truth, in a world with lucrative autocracies like Singapore and China. Instead, we have to accept the transformative power of ideas or, more directly, the technological, social, economic and political changes they bring about. From an American perspective, it is crucial to examine these changes, not only to understand their relevance as they transform the US, but also their effects in our evolving global relationships.Every development in international relations can be linked to some event that happened in the past, but never before has so much changed so quickly at such an expansive global level. In the first section of this article, I will examine the nature of recent technological changes in diplomacy and the larger derivative effects in society, which relate to the future of international politics. -

Grand Theories of European Integration Revisited: Does Identity Politics Shape the Course of European Integration?

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Grand theories of European integration revisited: does identity politics shape the course of European integration? Kuhn, T. DOI 10.1080/13501763.2019.1622588 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Journal of European Public Policy License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kuhn, T. (2019). Grand theories of European integration revisited: does identity politics shape the course of European integration? Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1213-1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1622588 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Journal -

The 'Great Debates' in International Relations Theory

The ‘Great Debates’ in international relations theory Written by IJ Benneyworth This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The ‘Great Debates’ in international relations theory https://www.e-ir.info/2011/05/20/the-%e2%80%98great-debates%e2%80%99-in-international-relations-theory/ IJ BENNEYWORTH, MAY 20 2011 International relations in the most basic sense have existed since neighbouring tribes started throwing rocks at, or trading with, each other. From the Peloponnesian War, through European poleis to ultimately nation states, Realist trends can be observed before the term existed. Likewise the evolution of Liberalist thinking, from the Enlightenment onwards, expressed itself in calls for a better, more cooperative world before finding practical application – if little success – after The Great War. It was following this conflict that the discipline of International Relations (IR) emerged in 1919. Like any science, theory was IR’s foundation in how it defined itself and viewed the world it attempted to explain, and when contradictory theories emerged clashes inevitably followed. These disputes throughout IR’s short history have come to be known as ‘The Great Debates’, and though disputed it is generally felt there have been four, namely ‘Realism/Liberalism’, ‘Traditionalism/Behaviouralism’, ‘Neorealism/Neoliberalism’ and the most recent ‘Rationalism/Reflectivism’. All have had an effect on IR theory, some greater than others, but each merit analysis of their respective impacts. First we shall briefly explore the historical development of IR theory then critically assess each Debate before concluding. -

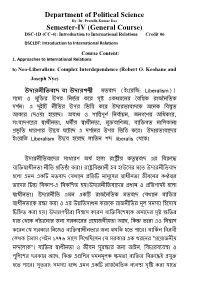

Department of Political Science Semester-IV (General Course)

Department of Political Science By: Dr. Prafulla Kumar Das Semester-IV (General Course) DSC-1D (CC-4): Introduction to International Relations Credit 06 DSC1DT: Introduction to International Relations Course Content: 1. Approaches to International Relations b) Neo-Liberalism: Complex Interdependence (Robert O. Keohane and Joseph Nye) ( : Liberalism)) ও উপ উপ উ ও ও প , , প , , , উ উপ উ Liberalism উ liberalis উ । উ উ - ।উ ও প । উ ও উ । উ প , ও ও প । প ১৭৭৬ " "। ও , ও প , প । প , ও । উ ও উৎ ও প ও প উ উ প , প প ও প প ও উ ও , , ও ও ও , উ , ও , , ও । উ প , ও উ - ৎ , উ প , ও ও । Complex interdependence Complex interdependence in international relations is the idea put forth by Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye. The term "complex interdependence" was claimed by Raymond Leslie Buell in 1925 to describe the new ordering among economies, cultures and races. The very concept was popularized through the work of Richard N. Cooper (1968). With the analytical construct of complex interdependence in their critique of political realism, "Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye go a step further and analyze how international politics is transformed by interdependence" . The theorists recognized that the various and complex transnational connections and interdependencies between states and societies were increasing, while the use of military force and power balancing are decreasing but remain important. In making use of the concept of interdependence, Keohane and Nye also importantly differentiated between interdependence and dependence in analyzing the role of power in politics and the relations between international actors. -

The Covid-19 Pandemic, Geopolitics, and International Law

journal of international humanitarian legal studies 11 (2020) 237-248 brill.com/ihls The covid-19 Pandemic, Geopolitics, and International Law David P Fidler Adjunct Senior Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations, USA [email protected] Abstract Balance-of-power politics have shaped how countries, especially the United States and China, have responded to the covid-19 pandemic. The manner in which geopolitics have influenced responses to this outbreak is unprecedented, and the impact has also been felt in the field of international law. This article surveys how geopolitical calcula- tions appeared in global health from the mid-nineteenth century through the end of the Cold War and why such calculations did not, during this period, fundamentally change international health cooperation or the international law used to address health issues. The astonishing changes in global health and international law on health that unfolded during the post-Cold War era happened in a context not characterized by geopolitical machinations. However, the covid-19 pandemic emerged after the bal- ance of power had returned to international relations, and rival great powers have turned this pandemic into a battleground in their competition for power and influence. Keywords balance of power – China – coronavirus – covid-19 – geopolitics – global health – International Health Regulations – international law – pandemic – United States – World Health Organization © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18781527-bja10010 <UN> 238 Fidler 1 Introduction A striking feature of the covid-19 pandemic is how balance-of-power politics have influenced responses to this outbreak.1 The rivalry between the United States and China has intensified because of the pandemic. -

The Future of Power

Transcript The Future of Power Joseph Nye University Distinguished Service Professor, Harvard University Chair: Sir Jeremy Greenstock Former British Ambassador to the United Nations (1998-2003) 10 May 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions, but the ultimate responsibility for accuracy lies with this document’s author(s). The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. Transcript: The Future of Power Joseph Nye: I’d like to be not a typical professor in the sense of not speaking in fifty-minute bytes at a time, but restrain myself and follow Jeremy’s good instruction. Having been a visitor to Ditchley a few times I know he runs a very tight ship. The argument that I make in this new book about the future of powers, that there are two large power shifts going on in this century. One, I call power transition, which is a shift of power among states, which is largely from West to East. -

No-Constructivists' Land: International Relations in Italy in the 1990S

Sonia Lucarelli and Roberto Menotti No-Constructivists’ Land: International Relations > in Italy in the 1990s Introduction theoretical debates that were frozen in time and provided the discipline in their There is one country in Europe respective countries with more strength where Constructivism has never and visibility. In Italy, however, this taken root: Italy. Although Con- opportunity seems to have been lost. No structivism in its various forms has been significant theoretical shift in the the most popular theoretical approach on discipline has taken place. Italian scholars the Continent, the Italian peninsula has have failed to make themselves more remained surprisingly immune to this visible in public debates in Italy and to “epidemic”. This situation is even more participate more fully in theoretical interesting if we take a closer look at the mainstream debates at the international Italian International Relations (IR) level. literature only to discover a certain We suggest that the puzzle of the predilection for the classics and for multi- post-Cold War “missed opportunity” calls disciplinary philosophically-embedded for an account that goes beyond the theory. What then is the reality of Italian traditional purely “external” explanation IR? What are its main features and the of IR developments in a given com- reasons underlying them? munity, and that also draws on the In this article, we investigate IR cultural-institutional context, namely, on theory in the peninsula of the Con- (i) the organisational characteristics of tinental IR archipelago that has been the the research environment (i.e. mainly the most successful in keeping secret its vices university system), (ii) the habits and and virtues. -

Liberalism in a Realist World: International Relations As an American Scholarly Tradition

Liberalism in a Realist World: International Relations as an American Scholarly Tradition G. John Ikenberry The study of international relations (IR) is a worldwide pursuit with each country having its own theoretical orientations, preoccupations and debates. Beginning in the early twentieth century, the US created its own scholarly traditions of IR. Eventually, IR became an American social science with the US becoming the epicentre for a worldwide IR community engaged in a set of research programmes and theoretical debates. The discipline of IR emerged in the US at a time when it was the world’s most powerful state and a liberal great power caught in a struggle with illiberal rivals. This context ensured that the American theoretical debates would be built around both power and liberal ideals. Over the decades, the two grand projects of realism and liberalism struggled to define the agenda of IR in the US. These traditions have evolved as they attempted to make sense of contemporary developments, speak to strategic position of the US and its foreign policy, as well as deal with the changing fashions and stand- ards of social science. The rationalist formulations of realism and liberalism sparked reactions and constructivism has arisen to offer counterpoints to the rational choice theory. Keywords: International Relations Theory, Realism, Liberalism The study of International Relations (IR) is a worldwide pursuit but every country has its own theoretical orientations, preoccupations and debates. This is true for the American experience—and deeply so. Beginning in the early twentieth cen- tury, the US created its own scholarly traditions of IR. -

From Geopolitics to the Anthropocene Written by Olaf Corry

The ‘Nature’ of International Relations: From Geopolitics to the Anthropocene Written by Olaf Corry This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The ‘Nature’ of International Relations: From Geopolitics to the Anthropocene https://www.e-ir.info/2017/10/15/the-nature-of-international-relations-from-geopolitics-to-the-anthropocene/ OLAF CORRY, OCT 15 2017 This is an excerpt from Reflections on the Posthuman in International Relations. An E-IR Edited Collection. Available now on Amazon (UK, USA, Ca, Ger, Fra), in all good book stores, and via a free PDF download. Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books here. International Relations (IR) has been criticised for its exclusively human perspective and for having ‘been little concerned with the vast variety of other, non-human populations of species and “things”’ (Cudworth and Hobden 2013, 644). One aim of post-humanist work is to find a way of including the natural world in a meaningful way into IR theory and analysis (see Kaltofen this volume). This is a challenge, but perhaps not an insurmountable one. After all, the discipline has roots in geopolitical analysis of how geography and climates affect world politics. The brief ‘natural history of IR’ that follows is necessarily a broad-brush depiction of how IR has (not) theorised and analysed the natural world in various ways (Corry and Stevenson 2017b). It shows that IR, although similar to sociology that became ‘radically sociological’ (Buttel 1996, 57), is not immune to concern for the natural world, but also that there is a long track record of either reifying or ignoring it. -

The Arctic Circle Is an Independent Nonprofit Organization Founded By

The Arctic Circle is an independent nonprofit organization founded by President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson of Iceland, former Greenland Prime Minister Kuupik Kleist, Alaska Dispatch and Arctic Imperative Summit founder Alice Rogoff and other prominent leaders on Arctic issues. The organization’s mission is to facilitate dialogue and build relationships to responsibly address rapid changes in the Arctic. Given the complexity of the issues involving the region and their global impact, the Arctic Circle provides a nonpartisan platform to convene a broad group of stakeholders for knowledge-sharing and cooperation. With sea ice levels at their lowest point in recorded history, the world’s G-20 political leaders, investors, business executives and the media are now recognizing the importance of the region and the challenges and opportunities this presents for all nations, for people around the world. ANNUAL ASSEMBLY In the fall of 2013, the Arctic Circle established itself as the preeminent international gathering of its kind. Held in Reykjavík, Iceland, at the Harpa Reykjavík Concert Hall and Conference Centre, the Arctic Circle Assembly brought together more than 1,200 international decision-makers from more than 40 nations, including Russia, the United States and other Arctic nations as well as Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and the United Kingdom. The event allowed existing institutions to reach a diverse global audience in a new and efficient way. Topics of focus included the latest scientific data on climate change and strategies to mitigate its effects, the prospects and challenges of Arctic energy development, how the Northern Sea Route will change global shipping, investment opportunities in the Arctic, and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.