A Fundamental Approach to a Walking Bass Line in Jazz Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

Year 11 Music Revision Guide

Year 11 Music Revision Guidance Name the musical instrument In the exam you will be asked to name different instruments that you can hear playing. If you do not play one of these instruments it can sometimes be quite difficult to pick out what each one sounds like. You will need to know what the different instruments of the orchestra sound like, what popular musical instruments sound like and what some world instruments sound like (sitar). It is worth you visiting www.dsokids.com or www.compositionlab.co.uk where you will be able to hear these instruments individually. Describing musical sounds For some questions in the exam you will need to describe what is happening in the music, in detail! If you are asked to comment on what is happening in the music you may need to describe what a particular instrument is doing, for example: ‘The left hand of the piano is playing ascending arpeggios’. The more detail you can provide, the better! Melodic movement You may be asked to describe what is happening in the melody of a song. Remember, this means the main tune. In popular music this is often the vocal line or in instrumental music it can be described as the instrument that has the main tune (the bit that you could whistle). It could move by STEP; this means it moves to the note next to it. It could move by LEAP; this means that the melody jumps from one note to another but misses some notes out in between. This could be a low note jumping to a high note or vice versa. -

Bassist Bryant Wilder's Fingerprints

NEWS MAGAZINE SHOP PLAYERS GEAR LEARN MEDIA WIN # ! + BASS CDS SUBSCRIBE NOW Bassist Bryant Wilder’s Get Cool Bass News! Fingerprints email address Subscribe By Bass Musician ! Published on August 18, 2020 ! Share " Tweet # Subscribe Bassist Robert Harper, Ride With Me Pluckwild Music Is thrilled to announce the release of the latest album from Bryant Wilder, Fingerprints, available everywhere on August 21, 2020. Fingerprints is an eclectic blend of incredible funk, salsa and gospel. # Interview with Bassist If you like Bruno Mars, you’ll love Fingerprints hit single, WtF ! Ricardo Martinez Trending (Where’s the Funk, featuring The Schtank Machine), an indisputable $ groove that will make you get to groovin’. BASS BOOKS ) The Beatles: Sgt Pepper’s Bass # 1 Bryant has held a bass since he was 14. Transcriptions ! The bassist, songwriter, arranger and producer has recorded and $ performed with artists such as Missy Elliot, The CD Hawkins Singers, BASS HISTORY ) Fretless Bass History New Kids On The Block and Shirley Caesar on many of the world # 2 greatest stages, including; Saturday Night Live, Radio City Music Hall, ! Interview with Bassist Carnegie Hall and Madison Square Garden (MSG). Fingerprints is his $ Mitch Friedman sophomore album, following The Right Track, which was released in BASS BOOKS ) 2004. Dream Theater Bass Transcriptions – Images # 3 And Words ! PluckWild Music is a production company devoted to making music $ that people want to hear. Productions blend live instrumentation and BASS BOOKS ) synthesizers that create intense low-end, head bobbing, feet tapping Tab Appendix – Grooving # songs that listeners hum for days. With Hybrid Techniques 4 ! Visit Bryant Wilder online at bryantwilder.com $ Interview with Bassist BASS GIVEAWAYS ) Teymur Phell The Summer Splash View More Music News Bass Musician Giveaway, 5 Sponsored by Elixir Strings ADVERTISEMENT You may also like.. -

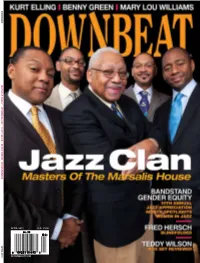

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

20Questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker

20questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker If Benny Goodman was the “King of Swing” periodically to continue his studies over the B-Town and Edward Kennedy Ellington was “the Duke,” next decade, leading a renowned IU-based then David Baker could be called “the Dean big band while expanding his artistic and Hero and Jazz of Jazz.” Distinguished Professor of Music at compositional horizons with musical scholars Indiana University and conductor of the Smithso- such as George Russell and Gunther Schuller. nian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, he is at home In 1966 he settled in the city for good and Legend performing in concert halls, traveling around the began what is now a world-renowned jazz world, or playing in late-night jazz bars. studies program at IU’s Jacobs School of Music. Born in Indianapolis in 1931, he grew up A pioneer of jazz education, a superlative in a thriving mid-20th-century local jazz scene trombonist forced in his early 30s to switch that begat greats such as J.J. Johnson and Wes to cello, a prolific composer, Pulitzer and Montgomery. Baker first came to Bloomington Grammy nominee and Emmy winner whose as a student in the fall of 1949, returning numerous other honors include the Kennedy 56 Bloom | August/September 2007 Toddler David in Indianapolis, circa 1933. Photo courtesy of the Baker family Center for the Performing Arts “Living Jazz Legend Award,” he performs periodically in Bloomington with his wife Lida and is unstintingly generous with the precious commodity of his time. -

Figured-Bass.Pdf

Basic Theory Quick Reference: Figured Bass Figured bass was developed in the Baroque period as a practical short hand to help continuo players harmonise a bass line at sight. The basic principle is very easy: each number simply denotes an interval above the bass note The only complication is that not every note of every chord needed is given a figure. Instead a convention developed of writing the minimum number of figures needed to work out the harmony for each bass note. The continuo player presumes that the bass note is the root of the chord unless the figures indicate otherwise. The example below shows the figuring for common chords - figures that are usually omitted are shown in brackets: Accidentals Where needed, these are placed after the relevant number. Figures are treated exactly the same as notes on the stave. In the example below the F# does not need an accidental, because it is in the key signature. On the other hand, the C# does to be shown because it is not in the key signature. An accidental on its own always refers to the third above the bass note. 33 For analytical purposes we will combine Roman Numerals (i.e. I or V) with figured bass to show the inversion. Cadential 6/4 Second inversion chords are unstable and in the Western Classical Tradition they tend to resolve rather than stand as a proper chord on their own. In the example below, the 6/4 above the G could be described as a C chord in second inversion. In reality, though, it resolves onto the G chord that follows and can better be understood as a decoration (double appoggiatura) onto this chord. -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

Figured-Bass Notation

MU 182: Theory II R. Vigil FIGURED-BASS NOTATION General In common-practice tonal music, chords are generally understood in two different ways. On the one hand, they can be seen as triadic structures emanating from a generative root . In this system, a root-position triad is understood as the "ideal" or "original" form, and other forms are understood as inversions , where the root has been placed above one of the other chord tones. This approach emphasizes the structural similarity of chords that share a common root (a first- inversion C major triad and a root-position C major triad are both C major triads). This type of thinking is represented analytically in the practice of applying Roman numerals to various chords within a given key - all chords with allegiance to the same Roman numeral are understood to be related, regardless of inversion and voicing, texture, etc. On the other hand, chords can be understood as vertical arrangements of tones above a given bass . This system is not based on a judgment as to the primacy of any particular chordal arrangement over another. Rather, it is simply a descriptive mechanism, for identifying what notes are present in addition to the bass. In this regime, chords are described in terms of the simplest possible arrangement of those notes as intervals above the bass. The intervals are represented as Arabic numerals (figures), and the resulting nomenclatural system is known as figured bass . Terminological Distinctions Between Roman Numeral Versus Figured Bass Approaches When dealing with Roman numerals, everything is understood in relation to the root; therefore, the components of a triad are the root, the third, and the fifth. -

Teaching Tuba Students to Be Complete Musicians Brandon E

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2017 Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians Brandon E. Cummings [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Educational Methods Commons, Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Brandon E., "Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians" (2017). Honors Research Projects. 577. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/577 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Running head: TEACHING TUBA STUDENTS TO BE COMPLETE MUSICIANS 1 Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians Brandon E. Cummings The University of Akron TEACHING TUBA STUDENTS TO BE COMPLETE MUSICIANS 2 Abstract The goal of music educators is to develop complete musicians who successfully learn and perform all musical concepts. One of the limitations of the band classroom is that performers are required to play a part that is specifically written with the needs of the ensemble in mind, and not the needs of the developing musician. -

General Catalog 2019–2020 / Edition 19 Academic Calendar 2019–2020

BERKELEY GENERAL CATALOG 2019–2020 / EDITION 19 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2019–2020 Spring Semester 2019 Auditions for Spring 2019 By Appointment Academic and Administrative Holiday Jan 21 First Day of Spring Instruction Jan 22 Last Day to Add / Drop a Class Feb 5 Academic and Administrative Holiday Feb 18 Spring Recess Mar 25 – 31 Last Day of Instruction May 10 Final Examinations and Juries May 13 – 17 Commencement May 19 Fall Enrollment Deposit Due on or before June 1 Fall Registration Jul 29 – Aug 2 Fall Semester 2019 Auditions for Fall 2019 By May 15 New Student Orientation Aug 15 First Day of Fall Instruction Aug 19 Last Day to Add/Drop a Class Sep 1 Academic and Administrative Holiday Sep 2 Academic and Administrative Holiday Nov 25 – Dec 1 Spring 2020 Enrollment Deposit Dec 2 Last Day of Instruction Dec 7 Final Examinations and Juries Dec 9 – 13 Winter Recess Dec 16 – Jan 21, 2020 Spring Registration Jan 6 – 10, 2020 Spring Semester 2020 Auditions for Spring 2020 By Oct 15 First Day of Spring Instruction Jan 21 Last Day to Add / Drop a Class Feb 3 Academic and Administrative Holiday Feb 17 Spring Recess Mar 23 – 27 Last Day of Instruction May 8 Final Examinations and Juries May 11 – 15 Commencement May 17 Fall 2020 Enrollment Deposit Due on or before June 1 Fall 2020 Registration July 27 – 31 Please note: Edition 19 of the CJC 2019 – 2020 General Catalog covers the time period of July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020. B 1 CONTENTS ACADEMIC CALENDAR ............... Inside Front Cover The Bachelor of Music Degree in Jazz Studies Juries ..............................................................