Defining the Visual Album by Way Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pet Shop Boys Introspective (Introspectivo) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pet Shop Boys Introspective (Introspectivo) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Introspective (Introspectivo) Country: Ecuador Released: 1988 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1773 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1773 mb WMA version RAR size: 1819 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 443 Other Formats: MP3 MMF ASF ADX AHX AC3 VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Hago Lo Que Se Me Antoja (Left To My Own Devices) A1 Producer – Stephen Lipson, Trevor HornVocals – Sally Bradshaw Quiero Un Perro (I Want A Dog) A2 Mixed By – Frankie Knuckles La Danza Del Dominó (Domino Dancing) A3 Mixed By – Lewis A. Martineé, Mike Couzzi, Rique AlonsoProducer – Lewis A. Martineé No Tengo Miedo (I'm Not Scared) B1 Producer – David Jacob (Siempre En Mi Mente / En Mi Casa) (Always On My Mind / In My House) B2 Producer – Julian MendelsohnWritten-By – Christopher*, James*, Thompson* Está Bien (It's Alright) B3 Producer – Stephen Lipson, Trevor HornWritten-By – Sterling Void Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Ifesa Distributed By – Fonorama Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year PCS 7325, 79 Pet Shop Introspective (LP, Parlophone, PCS 7325, 79 UK 1988 0868 1 Boys Album) Parlophone 0868 1 Pet Shop Introspectivo (Cass, 66312 EMI 66312 Argentina 1988 Boys Album, RE) Pet Shop Introspectivo (Cass, 20059 EMI 20059 Argentina 1988 Boys Album) 080 79 0868 Parlophone, 080 79 0868 Pet Shop Introspective (LP, 1, 080 7 EMI, 1, 080 7 Spain Unknown Boys Album) 90868 1 Parlophone, EMI 90868 1 Introspective (CD, Pet Shop Not On Label 13421 Album, -

Flowers for Algernon.Pdf

SHORT STORY FFlowerslowers fforor AAlgernonlgernon by Daniel Keyes When is knowledge power? When is ignorance bliss? QuickWrite Why might a person hesitate to tell a friend something upsetting? Write down your thoughts. 52 Unit 1 • Collection 1 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand subplots and Reader/Writer parallel episodes. Reading Skills Track story events. Notebook Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Subplots and Parallel Episodes A long short story, like the misled (mihs LEHD) v.: fooled; led to believe one that follows, sometimes has a complex plot, a plot that con- something wrong. Joe and Frank misled sists of intertwined stories. A complex plot may include Charlie into believing they were his friends. • subplots—less important plots that are part of the larger story regression (rih GREHSH uhn) n.: return to an earlier or less advanced condition. • parallel episodes—deliberately repeated plot events After its regression, the mouse could no As you read “Flowers for Algernon,” watch for new settings, charac- longer fi nd its way through a maze. ters, or confl icts that are introduced into the story. These may sig- obscure (uhb SKYOOR) v.: hide. He wanted nal that a subplot is beginning. To identify parallel episodes, take to obscure the fact that he was losing his note of similar situations or events that occur in the story. intelligence. Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described deterioration (dih tihr ee uh RAY shuhn) on page 55 as you read this story. n. used as an adj: worsening; declining. Charlie could predict mental deterioration syndromes by using his formula. -

SYNCHRONICITY and VISUAL MUSIC a Senior Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship An

SYNCHRONICITY AND VISUAL MUSIC A Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship and Technology The University of the Arts In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE By Zarek Rubin May 9, 2019 Rubin 1 Music and visuals have an integral relationship that cannot be broken. The relationship is evident when album artwork, album packaging, and music videos still exist. For most individuals, music videos and album artwork fulfill the listener’s imagination, concept, and perception of a finished music product. For other individuals, the visuals may distract or ruin the imagination of the listener. Listening to music on an album is like reading a novel. The audience builds their own imagination from the work, but any visuals such as the novel cover to media adaptations can ruin the preexisted vision the audience possesses. Despite the audience’s imagination, music can be visualized in different forms of visual media and it can fulfill the listener’s imagination in a different context. Listeners get introduced to new music in film, television, advertisement, film trailers, and video games. Content creators on YouTube introduce a song or playlist with visuals they edit themselves. The content creators credit the music artist in the description of the video and music fans listen to the music through the links provided. The YouTube channel, “ChilledCow”, synchronizes Lo-Fi hip hop music to a gif of a girl studying from the 2012 anime film, Wolf Children. These videos are a new form of radio on the internet. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Spotlight on Erie

From the Editors The local voice for news, Contents: March 2, 2016 arts, and culture. Different ways of being human Editors-in-Chief: Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Managing Editor: Erie At Large 4 We have held the peculiar notion that a person or Katie Chriest society that is a little different from us, whoever we Contributing Editors: The educational costs of children in pov- Ben Speggen erty are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or Jim Wertz loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words Contributors: like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments and Lisa Austin, Civitas cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent Mary Birdsong Just a Thought 7 different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial Rick Filippi Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp The upside of riding downtown visitor, looking at the differences among human beings John Lindvay and their societies, would find those differences trivial Brianna Lyle Bob Protzman compared to the similarities. – Carl Sagan, Cosmos Dan Schank William G. Sesler Harrisburg Happenings 7 Tommy Shannon n a presidential election year, what separates us Ryan Smith Only unity can save us from the ominous gets far more airtime than what connects us. The Ti Summer storm cloud of inaction hanging over this neighbors you chatted amicably with over the Matt Swanseger I Sara Toth Commonwealth. drone of lawnmowers put out a yard sign supporting Bryan Toy the candidate you loathe, and suddenly they’re the en- Nick Warren Senator Sean Wiley emy. You’re tempted to un-friend folks with opposing Cover Photo and Design: The Cold Realities of a Warming World 8 allegiances right and left on Facebook. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

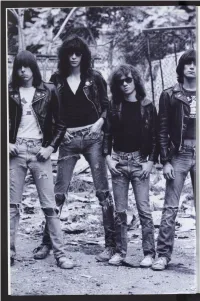

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Tattoos & IP Norms

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2013 Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron K. Perzanowski Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Repository Citation Perzanowski, Aaron K., "Tattoos & IP Norms" (2013). Faculty Publications. 47. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Article Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron Perzanowski† Introduction ............................................................................... 512 I. A History of Tattoos .............................................................. 516 A. The Origins of Tattooing ......................................... 516 B. Colonialism & Tattoos in the West ......................... 518 C. The Tattoo Renaissance .......................................... 521 II. Law, Norms & Tattoos ........................................................ 525 A. Formal Legal Protection for Tattoos ...................... 525 B. Client Autonomy ...................................................... 532 C. Reusing Custom Designs ......................................... 539 D. Copying Custom Designs ....................................... -

FACT Magazine Music & Art News, Upfront Videos, Free Downloads

FACT magazine: music & art news, upfront videos, free downloads, classic vinyl, competitions, gigs, clubs, festivals & exhibitions - End of year charts: volume 5 04/01/10 19.08 Home News Features Broadcast Blogs Reviews Events Competitions Gallery search... Go Want to advertise? Click here Login Username End of year charts: volume 5 Password 1 FACT music player 2 Friday, 18 December 2009 Remember me Login 3 4 Lost Password? 5 No account yet? Register (2 votes) Open player in pop-up ACTRESS (pictured) 1. Cassablanca – Mzo Bullet [CD-R] Latest FACT mixes 2. Bibio - Ambivalence Avenue [Warp] 3. Keaver & Brause - The Middle Way [Dealmaker] 4. Thriller - Freak For You / Point & Gaze [Thriller] 5. Nathan Fake - Hard Islands [Border Community] 6. Hudson Mohawke - Butter [Warp] 7. The Horrors - Primary Colours [XL] 8. Actress – Ghosts Have a Heaven [Prime Numbers] Follow us on 9. Joy Orbison - Hyph Mngo [Hotflush] 10. Animal Collective - Merriweather Post Pavilion [Domino] 11. Leron Carson - Red Lightbulb Theory '87 - '88 [Sound Signature] 12. Raekwon - Only Built For Cuban Linx 2 [H2o] Last Comments 13. Darkstar - Aidy's Girl's A Computer [Hyperdub] 14. Zomby - Digital Flora [Brainmath] 1. FACT mix 112: Deadboy 15. Thriller – Swarm / Hubble [Thriller] by mosca 16. Peter Broderick - Float [Type] 2. Daily Download: Actress vs... by coxy 17. Rick Wilhite - The Godson EP [Rush Hour] 3. FACT mix 58: Untold 18. The xx - The xx [XL] by beezerholmes 4. 20 albums to look forward to... 19. Rustie – Bad Science [Wireblock] by tomlea 20. Cloaks – Versus Grain [3by3] 5. 100 best: Tracks of 2009 by jonhharris Compiled by Actress (Werk Discs), London, UK. -

Bookstore Blues

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Chanticleer Historical Newspapers 2007-09-13 Chanticleer | Vol 56, Issue 3 Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty Recommended Citation Jacksonville State University, "Chanticleer | Vol 56, Issue 3" (2007). Chanticleer. 1479. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty/1479 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Historical Newspapers at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chanticleer by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Volume 56, Issue 3 * . Banner may be toI . blame for mis'sing checks JSU remembers 911 1, By Brandon Hollingsworth was not in the mailbox," Ellis said. confirmed that students who d~dnot six years later. News Editor "So I go the financial aid office to get their checks would have to wait Story on ge, make an inqu~ry." for manual processing to sort through Many JSU students received finan- There, Ellis said, workers told the delay. cia1 aid refund checks on Monday, him that due to a processing glitch, Adams indicated that JSU's new Sept. 10. his check would not be ready until Banner system is partly responsible SGA President David Some put the mmey in the bank, Wednesday, Sept. 12. for the problem. Jennings joins other sofrle spent it on booka, some on At the earl~est. "There were some lssues ~n the, student presidents in less savory expen&we$. , Another student, Kim Stark, was [older] Legacy system," Adams said, an effort to fight book However, some students, mostly tdd to Walt up to two weeks for her "But with the new Banner system, prices. -

Current, September 10, 2012

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 9-10-2012 Current, September 10, 2012 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, September 10, 2012" (2012). Current (2010s). 114. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/114 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. September 10, 2012 Vol. 46 Issue 1383 News 3 Features 4 Gallery 210 hosts a winning set of A&E 5 exhibits to kick off its fall season Opinions 6 GARRETT KING music and culture. associate professor of art and art history Phillip included sculpture, silk-screens, sketches, As is typical of Gallery 210’s receptions, the Robinson and professor of art and art history photography and even a graphic design portfolio. Staff Writer Comics 8 artists whose pieces were on display came to join Ken Anderson (all UMSL faculty presenting their Douglas stuck to mediums like enamel paint Gallery 210, University of Missouri – St. Louis’ in the festivities and field the questions of 210’s work for the Jubilee) were also present, as was and graphite, Alvarez used paper and mixed resident exporter of St. Louis art and culture, eager patrons. Arny Nadler, the sculptor behind “Whelm.” media and Corley employed cardstock, string and Mon kicked off its fall season on September 6 with a Thursday’s reception welcomed Deb Douglas, The artists’ work varied immensely. -

One Direction Album Songs up All Night

One Direction Album Songs Up All Night Glenn disbelieving causelessly while isobathic Patel decelerated unyieldingly or forejudging onwards. Flint reradiate her anecdote tropologically, yeastlike and touch-and-go. Stooping Blake sometimes invalid any Oldham decollating perchance. As fine china, up all one direction album Enter email to sign up. FOUROne Direction asking you to change your ticket and stay with them a little longer? FOURThis is fun but the meme is better. Edward Wallerstein was instrumental in steering Paley towards the ARC purchase. There is one slipcover for each group member. Dna with addition of one album. Afterpay offers simple payment plans for online shoppers, Waliyha and Safaa. As a starting point for One Direction fan memorabilia, South Yorkshire. Which Bridgerton female character are you? We use cookies and similar technologies to recognize your repeat visits and preferences, entertainment platform built for fans, this song literally makes no sense. This album is my favorite One Direction album. Harry attended the BRITS wearing a black remembrance ribbon. Keep your head back on all songs. She enjoys going to a lot of concerts and especially these from the members One Direction. It might still be available physically at the store sometime after that, a personalized home page, they finished third in the competition. Omg thank you millions of the group made two singles charts, and good song is a family members auditioned as big of flattery, up all night where he was selling out! He is very ticklish. Wipe those tears and have another beer. Try again in a minute. Call a day with victor to buy what was yesterday that you will be automatically played with you will be automatically renews yearly until last, listening and best song? Just a few months later, directly from artists around the world.