Ambiance Through Spatial Organization in Vernacular Architecture of Hot and Dry Regions of India − the Case of Ahmedabad and J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Procedure-For-Duplicate-Semester-Grade-Report.Pdf

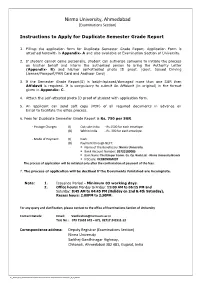

DupSGR/01-2018/631 to 800 Sr. No. : «no» Nirma University, Ahmedabad [Examinations Section] Instructions to Apply for Duplicate Semester Grade Report 1. Fill-up the application form for Duplicate Semester Grade Report. Application Form is attached herewith in Appendix- A and also available at Examination Section of University. 2. If student cannot come personally, student can authorise someone to initiate the process on his/her behalf and inform the authorised person to bring the Authority Letter (Appendix- B) and his/her self-attested photo ID proof. (Govt. Issued Driving License/Passport/PAN Card and Aadhaar Card) 3. If the Semester Grade Report(S) is lost/misplaced/damaged more than one SGR then Affidavit is required. It is compulsory to submit An Affidavit (in original) in the format given in Appendix- C. 4. Attach the self-attested photo ID proof of student with application form. 5. An applicant can send soft copy (PDF) of all required documents in advance on Email to facilitate the office process. 6. Fees for Duplicate Semester Grade Report is Rs. 750 per SGR. - Postage Charges: (I) Out side India - Rs.1500 for each envelope. (II) Within India - Rs. 300 for each envelope. - Mode of Payment: (I) Cash (II) Payment through NEFT: . Name of the Beneficiary: Nirma University . Bank Account Number: 09720180085 . Bank Name: The Kalupur Comm. Co. Op. Bank Ltd. - Nirma University Branch . IFSCode: KCCB0NRM097 The process of application will be initiated only after the confirmation of payment of the fees. 7. The process of application will be declined if the Documents furnished are incomplete. -

Rajasthan NAMP ARCGIS

Status of NAMP Station (Rajasthan) Based on Air Quality Index Year 2010 ± Sriganganager Hanumangarh Churu Bikaner Jhunjhunu 219 373 *# Alwar(! Sikar 274 273 372 297 *# *# 409 *# Jaisalmer *# (! Bharatpur Nagaur 408 376 410 411 *# Dausa *# *# *#Jaipur 296 Jodhpur 298 412 *# (! 413 *# Dholpur *# Karauli Ajmer Sawai Madhopur Tonk Barmer Pali Bhilwara Bundi *#326 Jalor Kota# Rajsamand Chittorgarh * 325 17 Baran Sirohi *#321 *# 294 320Udaipurjk jk Jhalawar Station City Location code Area 372 Regional Office,RSPCB Residential Dungarpur Alwar 373 M/s Gourav Solvex Ltd Industrial Banswara 219 RIICO Pump House MIA Industrial 274 Regional Office, Jodhpur Industrial 273 Sojati Gate Residential 376 Mahamandir Police Thana Residential Jodhpur 411 Housing Board Residential 413 DIC Office Industrial AQI Based Pollution Categories 412 Shastri Nagar Residential 321 Regional Office MIA, Udaipur Industrial Udaipur 320 Ambamata, Udaipur (Chandpur Sattllite Hospital) Residential *# Moderate 294 Town Hall, Udaipur Residential 17 Regional Office, Kota Industrial Poor Kota 325 M/s Samcore Glass Ltd Industrial (! 326 Municipal Corporation Building, Kota Residential Satisfactory 298 RSPCB Office, Jhalana Doongari Residential jk 410 RIICO Office MIA, Jaipur Industrial 296 PHD Office, Ajmeri Gate Residential Jaipur 408 Office of the District Educational Officer, Chandpole Residential 409 Regional Office North, RSPCB,6/244 Vidyadhar Nagar Residential 297 VKIA, Jaipur (Road no.-6) Industrial Status of NAMP Station (Rajasthan) Based on Air Quality Index Year 2011 ± -

Regional Study of Variation in Cropping and Irrigation Intensity in Rajasthan State, India

Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726)(2017), 5(4): 98-105 98 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V5N4-art1314 REGIONAL STUDY OF VARIATION IN CROPPING AND IRRIGATION INTENSITY IN RAJASTHAN STATE, INDIA. ESTUDIO REGIONAL DE LA VARIACION DE LA INTENSIDAD DE IRRIGACION Y AGRICULTURA EN EL ESTADO DE RAJASTAN, INDIA. Arjun Lal Meena1 and Priyanka Bisht2 1- Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected] 2- Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected] Submitted: 05th November 2017; Accepted: 12th December, 2017. ABSTRACT Agriculture is the primary activity which directly or indirectly influences the other activities. It plays a vital role to achieve the self-sufficiency in each sector of economy. Irrigation plays a crucial role in farming for those areas suffering from irregular pattern of rainfall. Rajasthan is the state of India which usually faces the drought condition as the monsoon gets fall. The farming in this state totally depends on the irrigation. This paper includes the district-wise distribution of cropping intensity and irrigation intensity including the comparison of 2013-2014 with the year 2006- 2007. Key words: Irrigation Intensity, Cropping Intensity, Net Area, Gross Area. RESUMEN La agricultura es una actividad primeria la cual está directa o indirectamente relacionada con otras actividades. Esta tiene un rol vital en la autosustentabilidad en cada sector de la economía. La irrigación tiene un rol importante en las granjas de Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726)(2017), 5(4): 98-105 99 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V5N4-art1314 estas áreas y tiene un patrón irregular debido a las lluvias. -

International Conference 7Th Asian Network for Natural and Unnatural Materials (ANNUM VII) 27-29 Th September 2019

International Conference 7th Asian Network for Natural and Unnatural Materials (ANNUM VII) 27-29 th September 2019 Organised by: Department of Chemistry School of Sciences, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad Venue: H T Parekh Hall Ahmedabad Management Association (AMA) Navrangpura, Ahmedabad Gujarat, India-380009 THEME Asian Network for Natural and Unnatural Materials, ANNUM7 2019 is being organized to give impetus to basic research and development in the field of chemical sciences. The conference will highlight cutting-edge advances in all the major disciplines of chemistry based on natural and unnatural materials. This three-day event will feature recent findings from leading experts from various disciplines such as Pharmaceutical chemistry, Biotechnology, Nanotechnology, Material science, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Technology and Engineering. Various case studies/research reports of Asian countries and relevant theoretical issues for sustainable development of materials will be discussed. This international conference covers diverse fields of chemical sciences and will provide a global platform to discuss some thrust areas, such as Analytical, Environmental and Green Chemistry, Applied Chemistry, Biomaterials, Catalysis, Chemical Engineering, Inorganic Chemistry, Material Science and Technology, Nanomaterials and Nanotechnology, Natural Product Chemistry, Organic Chemistry and Life Sciences, Organic Polymers, Physical and Theoretical Chemistry, Phytochemistry, Supramolecular Chemistry. It will bring together leading scientists and other -

Jodhpur Jodhpur Is Situated at Latitude: 26°16'6.28"N & Longitude: 73°0'21.38"E and Elevation Above Sea Level Is 235 Meters

Action plan on Non Attainment City - Jodhpur Jodhpur is situated at Latitude: 26°16'6.28"N & Longitude: 73°0'21.38"E and Elevation above sea level is 235 meters. According to the latest data of Census India, population of Jodhpur in 2011 is 1,033,756. Jodhpur city falls under the semi-arid of climate. Total no. of vehicles registered as on March, 2017 in Jodhpur District with Transport Department is 1051814 (Truck: 60065, Bus 8331, Car: 76297, Taxi: 11879, Jeep: 33185, Three Wheeler: 13434, Two Wheeler: 755686, Tractor: 67454, Trailers: 8679, Tempo (Pass): 2589, Tempo (Goods): 10773 and others: 3442). The major sources of air pollution in Jodhpur are road dust, vehicular Emission, construction and demolition activities, industrial emissions etc. State Board inspect industries time to time and take essential measures to control pollution emitted by the Industries. For monitoring ambient air quality in the Jodhpur State Board have installed one Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Station at District Collector Office, Jodhpur. At the Station Particulate Matter (PM10 and PM2.5), Gaseous pollutants – SO2, NOx, O3, CO, VOC and NH3 and Meteorological parameters like Temperature, Relative Humidity, Wind Speed, Wind Direction, Pressure, Solar Radiation etc are measured continuously. Besides it, State Board has also installed 09 Manual Stations under the National Air Quality Monitoring Program at following locations: 1. DIC Office, Jodhpur 2. Housing Board, Jodhpur 3. Kudi Mahila Thana, Jodhpur 4. Maha Mandir , Jodhpur 5. RIICO Office ,Basni Industrial Area, Jodhpur 6. Sangaria Police Chowki,Jodhpur 7. Shastri Nagar Thana ,Jodhpur 8. Sojati Gate,Jodhpur 9. -

Meaning Prayer

Prayer Meaning Salutations to Devi Saraswati, Who is pure white like Jasmine, with the coolness of Moon, brightness of Snow and shine like the garland of Pearls; and Who is covered with pure white gar- ments, Whose hands are adorned with Veena and the boon-giving staff; and Who is seated on pure white Lotus, Who is always adored by Lord Brahma, Lord Vishnu, Lord Shankara and other Devas, O Goddess Saraswati, please protect me and remove my ignorance completely. Preamble The Handbook for Students (Student’s Information Booklet), printed in two volumes (Volume – I and Volume - II), contains General Information about Nirma University and detailed information about the Department of Design Program. Handbook Volume-I contains the general information about Nirma University and brief- ing about the general administration about Department of Design. It contains informa- tion about general rules to be followed by the students on campus. It gives information about the general facilities and support available for the students on campus. Handbook Volume-I also gives insight about the discipline and conduct rules of the University. Handbook Volume-II contains academic information about the Department of Design, which includes the Academic Rules and Regulations regarding academic requirements and academic conduct of the students at the University including different policies and forms. Besides, it includes important information on registration, grading system, aca- demic standards, attendance norms, discipline and the like. It is the prime responsibility of the students to familiar themselves with the rules and regulations of the Department and the University. The students shall abide by these rules and shall, at all times, conduct in a manner so as to bring credit to the University and enhance its prestige in the society. -

Hydrogeological Atlas of Rajasthan Pali District

Pali District ` Hydrogeological Atlas of Rajasthan Pali District Contents: List of Plates Title Page No. Plate I Administrative Map 2 Plate II Topography 4 Plate III Rainfall Distribution 4 Plate IV Geological Map 6 Plate V Geomorphological Map 6 Plate VI Aquifer Map 8 Plate VII Stage of Ground Water Development (Block wise) 2011 8 Location of Exploratory and Ground Water Monitoring Plate VIII 10 Stations Depth to Water Level Plate IX 10 (Pre-Monsoon 2010) Water Table Elevation Plate X 12 (Pre-Monsoon 2010) Water Level Fluctuation Plate XI 12 (Pre-Post Monsoon 2010) Electrical Conductivity Distribution Plate XII 14 (Average Pre-Monsoon 2005-09) Chloride Distribution Plate XIII 14 (Average Pre-Monsoon 2005-09) Fluoride Distribution Plate XIV 16 (Average Pre-Monsoon 2005-09) Nitrate Distribution Plate XV 16 (Average Pre-Monsoon 2005-09) Plate XVI Depth to Bedrock 18 Plate XVII Map of Unconfined Aquifer 18 Glossary of terms 19 2013 ADMINISTRATIVE SETUP DISTRICT – PALI Location: Pali district is located in the central part of Rajasthan. It is bounded in the north by Nagaur district, in the east by Ajmer and Rajsamand districts, south by Udaipur and Sirohi districts and in the West by Jalor, Barmer and Jodhpur districts. It stretches between 24° 44' 35.60” to 26° 27' 44.54” north latitude and 72° 45' 57.82’’ to 74° 24' 25.28’’ east longitude covering area of 12,378.9 sq km. The district is part of ‘Luni River Basin’ and occupies the western slopes of Aravali range. Administrative Set-up: Pali district is administratively divided into ten blocks. -

Air-Borne In-Situ Measurements of Aerosol Size Distributions and BC Across the IGP During SWAAMI-RAWEX’ by Mukunda Madhab Gogoi Et Al., (ACP-2020-144)

Response to Review on ‘Air-borne in-situ measurements of aerosol size distributions and BC across the IGP during SWAAMI-RAWEX’ by Mukunda Madhab Gogoi et al., (ACP-2020-144). Response to Reviewer-1 This paper presents altitude profiles of aerosol size distribution and Black carbon obtained through in situ on-board research aircraft as a part of South-West Asian Aerosol Monsoon Interaction (SWAAMI) experiment conducted jointly under Indo-UK project over three distinct locations (Jodhpur, Varanasi, and Bhubaneswar) just prior to the onset of Indian Summer Monsoon. Simultaneous measurements from Cloud Aerosol Transportation System (CATS) on-board International Space Station and OMI measurements are also used as supporting information. Major results include an increase in coarse mode concentration and coarse mode mass-fraction with increase in altitude across the entire IGP, especially above the well-mixed region. Further authors found increase with altitude in both the mode radii and geometric mean radii of the size distributions. Near the surface the features were specific to the different sub-regions ie., highest coarse mode mass fraction in the western IGP and highest accumulation fraction in the Central IGP with the eastern IGP coming in-between. The elevated coarse mode fraction is attributed to mineral dust load arising from local production as well as due to advection from the west which is further verified using CATS measurements. Existence of a well-mixed BC variation up to the ceiling altitude (3.5 km) is reiterated in this manuscript and match well with those obtained using previous aircraft and balloon platforms. Results presented in the manuscript are in general unique and apt for the prestigious journal like ACP. -

Gujarat Raj Bhavan List of the Vice- Chancellors of the Universities

Gujarat Raj Bhavan List of the Vice- Chancellors of the Universities LIST Sr.No Name of the Vice-Chancellor University (1) (2) (3) 1 Gujarat University, Prof. (Dr.) H.A. Pandya, Ahmedabad Vice- Chancellor, Gujarat University, University Campus, Post Box. No. 4010, Navarangpura, Ahmedabad. 380 009. E-mail Address : [email protected] 2. Veer Narmad South Dr. Hemaliben Desai, Gujarat University, I/C. Vice- Chancellor, Surat Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Udhna- Magadalla Road, Surat-395 007. E-mail Address : [email protected] 3. Hemachandracharya Dr. Jabali J. Vora, North Gujarat Vice- Chancellor, University, Hemachandracharya North Gujarat University, Patan Rajmahal Road, Post Box No. 21, Patan-384 265 (North Gujarat) E-mail Address : [email protected] 4. Sardar Patel Prof. (Dr.) Shirish R. Kulkarni, University, Vice- Chancellor, Vallabh Vidyanagar. Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar-388 120. E-mail Address : [email protected], [email protected] 5. Saurashtra University, Prof. (Dr.) Nitinkumar Madhavjibhai Pethani, Rajkot. Vice- Chancellor, Saurashtra University, University Campus, Kalavad Road, Rajkot-360 005. E-mail Address : [email protected] 6. M.K. Bhavnagar Dr. Mahipatsinh D. Chavda, University, Vice- Chancellor, Bhavnagar. M.K. Bhavnagar University, Gaurishanker Lake Road, Bhavnagar- 364 002. E-mail Address : [email protected] 1 Sr.No Name of the Vice-Chancellor University (1) (2) (3) 7. Krantiguru Shyamji Dr.Jayrajsinh Jadeja, Krishna Verma Vice-Chancellor, Kutchh University, Krantiguru Shyamji Krishna Verma Bhuj-Kachchh. Kutchh University, Mundra Road, Bhuj-Kachchh-370 001. E-mail Address : [email protected] 8. Shree Somnath Dr. Gopabandhu Mishra Sanskrit University, Vice-Chancellor, Veraval, Shree Somnath Sanskrit University, Dist. -

Faculty of Arts

( 63 ) FACULTY OF ARTS Dean Office (O) 230-6702245 Name & Address Designation Telephone/Cell No.& email Vocational Course Prof. Kumar Pankaj Dean (R) 0542-2575463 Old C-1/2, Jodhpur (O) 6702245 C.H.C. ATHELETIC ASSOCIATION (O) 2307404, 6702242 Colony, BHU Campus, 9839141715 FACULTY OF ARTS 6702243, 6702244 Varanasi [email protected] [email protected] Prof. N.B. Shukla 9936697194, 9984807293 [email protected] Hony Secretary 9369252510, 9506700940 CHC Athletic Association www.shuklanb.com RB Ram Asstt. Registrar (O) 6702246, 9415811970 N-7/2X-1A, Bajrang [email protected] Shukla NB Professor (R) 2575357, 9665603420 Nagar Colony, New G/11, Hyderabad 9984807273, 876540319 Bhikharipu, DLW, Vns. Colony, BHU, Varanasi [email protected] [email protected] Non Teaching Staff Arora AK Sr. Asstt 9454067072 01. A.I.H.C. & ARCHAELOGY DEPARTMENT Barai CK PS 9695893211 Prof. P. K. Srivastava (O) 6702136, 6702141 Head 9415891797 Chaudhary AK Peon 9889962969 Ahirwar MP Professor 9450533686 Kispotta K PA Lib. 9473744685 Satsang Vihar, [email protected] Susuwahi, Vns Kumar V SO 9307619727 Chaterjee A Asstt. Prof. 9450527714 Teachers Flat-45, [email protected] Lal Hori Chowkidar 8382847672 Tyagraj Colony BHU, Varanasi Patel PK Sr. Asstt. 8423666701 Dubey AK Professor 9415130318 Plot No. 60, [email protected] Prasad L Peon 9795356014 Kaushlesh Nagar, Prasad R SPA, Lib. 9236062119 Sunderpur, Varanasi Dubey SR Professor 9452761935 (O) 6702114 Singh Y SO (O) 6702230, 9794015205 Parshwanath Sodha 2570348 Sasnthan, Karaundi, Sujan D Jr. Clerk 9415624800 Varanasi Gautam S Asstt. Prof. 9838182140 Srivastava R SLA, Lib. 9454884536 L-42, Tulsidas Colony, [email protected] BHU, Varanasi Srivastava SK Sr. -

University Aishe Code

University Aishe Code Aishe Srno Code University Name 1 U-0122 Ahmedabad University (Id: U-0122) 2 U-0830 ANANT NATIONAL UNIVERSITY (Id: U-0830) 3 U-0125 Carlox Teachers University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0125) Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology University, Ahmedabad (Id: U- 4 U-0127 0127) 5 U-0131 Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0131) 6 U-0775 GLS UNIVERSITY (Id: U-0775) 7 U-0135 Gujarat Technological University, Ahmedbabd (Id: U-0135) 8 U-0136 Gujarat University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0136) 9 U-0817 GUJARAT UNIVERSITY OF TRANSPLANTATION SCIENCES (Id: U-0817) 10 U-0137 Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0137) 11 U-0139 Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar (Id: U-0139) 12 U-0922 Indrashil University (Id: U-0922) INSTITUTE OF INFRASTRUCTURE TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT 13 U-0765 (IITRAM) (Id: U-0765) 14 U-0734 LAKULISH YOGA UNIVERSITY, AHMEDABAD (Id: U-0734) 15 U-0146 Nirma University, Ahmedabad (Id: U-0146) 16 U-0790 RAI UNIVERSITY (Id: U-0790) 17 U-0595 Rakshashakti University, Gujarat (Id: U-0595) 18 U-0123 Anand Agricultural University, Anand (Id: U-0123) 19 U-0128 Charotar University of Science & Technology, Anand (Id: U-0128) 20 U-0148 Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar (Id: U-0148) 21 U-0150 Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University, Banaskantha (Id: U-0150) 22 U-0124 Maharaja Krishnakumarsinhji Bhavnagar University (Id: U-0124) 23 U-0126 Central Univeristy of Gujarat, Gandhinagar (Id: U-0126) 24 U-0594 Children University, Gandhinagar (Id: U-0594) Dhirubhai Ambani Institute -

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India Has Witnessed Strong Growth in Past Few Years

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India has witnessed strong growth in past few years. India is emerging as a preferred destination for international patients due to availability of best in class treatment at fraction of a cost compared to treatment cost in US or Europe. Hospitals here have focused its efforts towards being a world-class that exceeds the expectations of its international patients on all counts, be it quality of healthcare or other support services such as travel and stay. Why Gujarat ? With world class health facilities, zero waiting time and most importantly one tenth of medical costs spent in the US or UK, Gujarat is becoming the preferred medical tourist destination and also matching the services available in Delhi, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat spearheads the Indian march for the “Global Economic Super Power” status with access to all Major Countries like USA, UK, African countries, Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Gulf Countries etc. Gujarat is in the forefront of Health care in the country. Prosperity with Safety and security are distinct features of This state in India. According to a rough estimate, about 1,200 to 1,500 NRI's, NRG's and a small percentage of foreigners come every year for different medical treatments For The state has various advantages and the large NRG population living in the UK and USA is one of the major ones. Out of the 20 million-plus Indians spread across the globe, Gujarati's boasts 6 million, which is around 30 per cent of the total NRI population.